The ancient history of Afghanistan, a landlocked country in Central Asia, is full of fascinating cultures, from early nomadic tribes to the realms of Achaemenid Persia, the Seleucids, the Mauryans, the Parthians, and Sasanians, as well as steppe people like the Kushans or the Hephthalites. All these civilizations have left their mark on the region, leading to a unique blend of cultures and religions.

Geography & Peoples

Afghanistan shares borders with Iran to the west, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan to the north, Tajikistan to the northeast, China to the east and northeast, and Pakistan to the southeast. The country is one of the main connectors between Central and South Asia. This fact has given the territory tremendous geopolitical importance. Throughout the millennia, vital strategic invasion routes and trade ways led through the areas of contemporary Afghanistan. Notable examples are the Silk Road and the Khyber Pass.

Still, passage through Afghanistan has challenges. Most of the country varies between mountainous terrain and deep, narrow valleys. The mighty Hindu Kush range separates the plains in the north and southwest. The southern part is comparably arid, and the Registan Desert covers large areas in the Kandahar province.

As in early times, many of the population today are modest farmers or herders. Especially the northern parts provide fertile grounds. Therefore, rivers and streams have always played a vital role in urban structures and early farming. Ancient cultures have developed close to waterways such as the Helmand, Kabul, and Oxus rivers.

As Afghanistan is rich in minerals, mining activities have played a pivotal role since ancient times. Unfortunately, the mountainous and rough terrain makes it challenging to reach these resources. Early inhabitants of Afghanistan, therefore, had to work hard to harvest precious ores.

Despite the strong roots of Islam in the population today, the country has seen a variety of influences. The first well-recorded rulers of the area were the Achaemenid Persians. Yet, they were far from the earliest people to shape the region.

From First Settlers to Early Civilizations

Excavated artifacts and bones suggest people lived in Afghanistan at least 52,000 years ago. While we know little about the emergence of cities in Afghanistan, different finds have provided insight. For instance, the Helmand culture erected settlements such as the Mundigak site in today's province of Kandahar. Afghanistan also had urban areas associated with the Harrapans, more commonly known as the Indus Valley Civilization.

The Oxus civilization, also called Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), was situated in the northern area of present-day Afghanistan. Scholars know they were an agricultural society with fortified settlements and vast metalworking skills that influenced the area from circa 2,200 BCE to circa 1,700 BCE. Indo-Aryan people began moving eastwards from Central Asia towards the Indian subcontinent between c. 2,000 BCE to c. 1,200 BCE. They interacted with the people and cultures already present in Afghanistan, such as the BMAC.

Becoming Part of Empires

From circa 500 BCE onwards, various civilizations shaped the region's history. Two of those were Gandhara and Kamboja, who belonged to ancient India's 16 Mahājanapadas ("great kingdoms"). They wielded considerable political importance in what is today eastern Afghanistan.

The Medes were the first to seamlessly incorporate most of Afghanistan into their territory. These Iranian people established circa 700 BCE one of the first realms in the Near East, stretching from the southern shore of the Black Sea to Pakistan.

By 550 BCE, the Medes had been toppled and integrated into the Persian Achaemenid Empire, which shaped world history for the next 200 years. Darius I (l. c. 550-486 BCE) was a pivotal figure. By his death, he had realized extensive cultural, architectural, and infrastructural achievements in the provinces (satrapies) of the Persian Empire. He was also a follower of Zoroastrianism, the central monotheistic faith of the Achaemenid Empire, and boosted its spread.

Alexander the Great

By 327 BCE, Alexander the Great (l. 21 July 356 BCE – 323 BCE) eventually gained control over the satrapy of Bactria. The region covered areas of modern Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan, and its inhabitants had been a thorn in Alexander's side for a while. Bactrian horse riders belonged to the most fearsome within the Persian armies, with whom the Macedonian conqueror clashed in his campaign.

![Alexander the Great [Profile View]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/1047.jpg?v=1660133770)

Even after the defeat of the Great King Darius III (r. 336-330 BCE), the satrap (regional ruler) Bessus of Bactria (r. 336–329 BCE) proved troublesome. He and other satraps murdered Darius III when it became clear that the king could no longer stand up to Alexander. This betrayal robbed Alexander of the opportunity to strengthen his legitimacy via his defeated rival.

Also, the satraps resisted Alexander's advance ferociously. Even the capture and imminent execution of Bessus could not halt this. A nobleman known as Oxyartes continued the fight and only surrendered after Alexander took the fortress of Sogdian Rock. There Alexander saw his future wife and Oxyartes' daughter, famously beautiful Roxanne, for the first time. Their marriage finally sealed Macedonian control over the region.

With refreshed troops and the Achaemenid Empire at last under his rule, Alexander looked ahead to India. Unfortunately, that campaign did not go well, and he had to return to Afghanistan. While ruling, Alexander created multiple cities in the region and implemented considerable Hellenic influences and political changes. Additionally, Alexander tried his best to bring together the people of Greece and Persia. He died before realizing this goal, though.

Alexander's Legacy

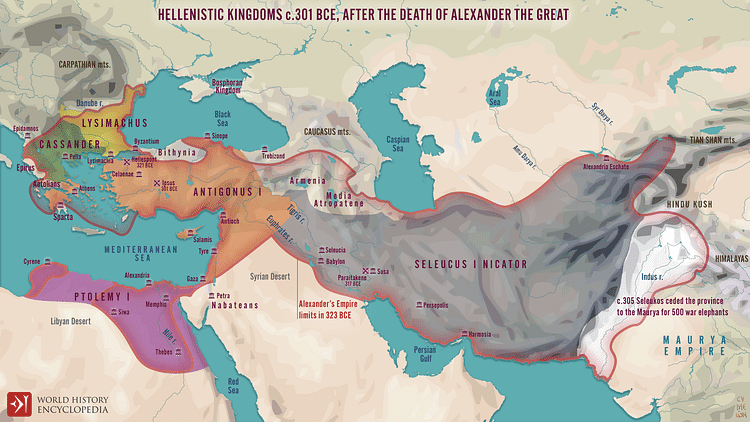

Alexander's vast empire did not survive for long after his death. Without a clear successor, a struggle for leadership broke out among the commanders of the realm. These so-called Wars of the Diadochi led to years of rivalry, scheming, and unrest. Roxanne and her son from Alexander belonged to the most prominent victims of this turbulent time.

Long-term control over the eastern parts, including areas of modern Afghanistan, went to Seleucus I Nicator (l. c. 358-281 BCE). So the Seleucid dynasty began. Seleucus ruled with an iron fist and pushed the boundaries of his empire as far as the Indus River. Then he started a climactic fight with India's Mauryan rulers in 305 BCE. The Mauryan Empire directly resulted from Alexanders' withdrawal from West India. Its founder Chandragupta Maurya (r. c. 321 - c. 297 BCE), seized the opportunity created by the failed incursion and pushed aggressively for control in the Indus Valley and northwest India.

Seleucus' efforts to take back the former regions of Macedonian rule did not succeed. The conflict with the Mauryans ended in 303 BCE, and Seleucus ceded large areas, including parts of southern Afghanistan, to Chandragupta. He received 500 war elephants in exchange, and a marital alliance strengthened the agreement.

Mauryan influence in Afghanistan held for more than 100 years. Notably, Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka the Great (r. 268-232 BCE) played a pivotal role. The king would become a genuine follower and supporter of Buddhism later in life. He spread his beliefs via proclamations and edicts engraved in rocks and pillars. As a result, Buddhism became an influential religion alongside Zoroastrianism.

The Rise of the Greco-Bactrians & Parthians

Around 250 BCE, the Seleucids gradually lost control of their eastern domains due to internal unrest and struggles in the west. These weakened their grip on the areas of modern Afghanistan. So, new powers took advantage of this situation. The Greco-Bactrian kingdom emerged around 250 BCE when the satrap of Bactria and the surrounding provinces revolted against his Seleucid ruler. Today's knowledge about Greco-Bactria stems mainly from coins and a few remarks in historical texts. The kingdom had great foundations for prosperity due to its fertile areas and various trade routes. In the west, a new threat began to appear, though.

A nomadic tribe called Parni, possibly related to the Scythians, began pushing south from their original homelands. Their prolonged invasion of the area allowed them to establish themselves as rulers c. 247 BCE. These people would be known as the Parthians, based on the name of the region they initially subjugated.

Until 200 BCE, the various factions attempted to stabilize or boost control. Especially the Seleucids tried to reclaim their lost territories in the east. Antiochus III (r. 223-187 BCE) achieved brief success through multiple victories against the Parthians and Greco-Bactrians until the end of his eastern campaign in 205 BCE. However, he allowed his defeated enemies to stay in power to renew their loyalty.

The Fall of the Established Powers

In the end, the Parthians and Greco-Bactrians profited from the weaknesses of the Seleucids and Mauryans. Antiochus III suffered multiple defeats against the Roman Republic and had to agree to harsh peace terms in 188 BCE. The subsequent loss of land, military power, and resources crippled the Seleucids. Over the following decades, the once-mighty empire disintegrated due to revolts and (civil) wars. On the other side, the Mauryan empire slowly crumbled after the death of Ashoka. The Greco-Bactrians used the instability to extend their reach as far as modern India. This expansion formed the Indo-Greek Kingdoms, which were politically self-dependent and became places of a unique blend of Hellenistic and Indian culture.

However, internal unrest and division plagued the Greek kingdoms in Central Asia. A man called Eucratides (r. c. 171–145 BCE) overthrew his Greco-Bactrian king circa 171 BCE and later marched against the Indo-Greeks. Their ruler, Menander I (r. c. 165–130 BCE), ultimately managed to eliminate the invaders. He is generally considered the greatest of the Indo-Greek rulers and was a famous patron of Greco-Buddhism.

On the other hand, the Parthians proved to be ambitious western neighbors. Parallel or shortly after Eucratides' advances, the Parthians under Mithridates I (r. 165–132 BCE) dealt severe blows to the Greco-Bactrians. Possibly the Greco-Bactrians even ended up as vassals to the Parthians. The latter gradually became the dominant power in the region by taking substantial portions of Seleucid land in the west.

The Saka & Yuezhi Invasions

The ultimate downfall of Greco-Bactrian rule appeared from the north. At the beginning of the 2nd century BCE, a confederation of nomadic tribes called the Yuezhi left their homelands in today's western Mongolia and China. On their way southwest, they pushed a Scythian tribe called the Saka out of the steppes of contemporary Kazakhstan. The Saka, in turn, moved towards the Parthian Empire and the Greek domains. Some eventually reached as far as India and established a culture known as Indo-Scythians.

The Parthians could withstand the ensuing waves of nomadic people, though with difficulties. Yet, the Greek kingdoms in the region steadily weakened due to pressure from Parthia and the roaming newcomers. As a consequence, they became increasingly fractured in the following century. Hellenistic authority in the area finally succumbed circa 10 CE to the advances of the Yuezhi, (Indo-)Scythians, and (Indo-)Parthians.

The Indo-Parthian Kingdom was an independent domain in parts of contemporary Pakistan, India, and Afghanistan. Historians reconstruct its history mainly from coinage and rare mentions in ancient writings. Its establishment traces back to Gondophares I (r. c. 19 – c. 46 CE), who seceded from the Parthian rule in 19 CE.

The political support for this power grab might have come from Gondophares' relation with the Parthian noble house of Suren. Because of their significant influence, some historians refer to the Indo-Parthian Kingdom as the Suren Kingdom. After Gondophares' nearly 30-year-long rule, his successors could not prevent the kingdom's fragmentation. Still, they were able to retain control in the area of southern Afghanistan until its conquest by the Sasanians in 225 CE.

The Kushan Empire

Most of our knowledge of the Kushan Empire stems from coins and Chinese records. According to these sources, the Yuezhi eventually settled within the region of Bactria. They began to blend in with the existing population, making the area a base for their future expansion.

While the loosely aligned tribes initially had no uniform government, one of them (called the Kushans) grew more dominant over time. The term Kushan Empire typically applies since the rule of Kujula Kadphises (r.c. 30 CE - c. 80 CE). Shortly before or during his reign, the Yuezhi confederation became a political unit.

In the following eastwards expansion, the Kushans took large parts of (Indo-)Parthian lands. They adopted elements and traditions of the Hellenistic culture in Bactria next to other influences. Within their borders, many belief systems existed, ranging from Zoroastrianism to Greek cults, Iranian religions, Hinduism, and Buddhism.

Mainly Buddhism prospered in the Kushan Empire, especially during the patronage of Kanishka the Great (r. c. 127–c. 150 CE). Under his leadership, the Kushans extended their reach into various regions of Asia, including Northern India and possibly even China. During its peak, the Kushan Empire was a focal point of intercultural trade between the East and West, linking great civilizations like Han China and the Roman Empire via the Silk Route.

Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian Empire toppled the Parthian Empire and the remains of the Indo-Parthians in 224 CE. Named after an ancestor of its founder Ardeshir I (l. c. 180-241 CE), the Persian Sasanians used the weakened state of the Parthian rule. This situation occurred due to prolonged internal conflicts and warfare with the Romans.

Under their authority, the region saw a resurgence of Iranian culture. As one of many notable things, Zoroastrianism became once more the state religion. Some sources also claim that during the Sasanian rule, the term "Afghan" or "Abgan" appeared for the first time and described the tribal ancestors of today's Pashtuns.

Eventually, the Kushans had to make way for the Sasanians as well. Shortly after or during the reign of Vasudeva I (r. c. 191–232 CE), generally considered the last "Great Kushan", the Kushan Empire split into multiple parts. This fragmentation and general unrest in the Asian continent deeply affected trade interactions between West and East and consequently Kushan prosperity.

The Sasanian Empire soon subjugated the Western Kushans in the middle of the 3rd century CE, most likely under the leadership of Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE). It installed nobles known as Kushano-Sasanians or Kushanshas (Kings of the Kushans)as vassal governors. The Eastern Kushans would stay in power until the Gupta from India defeated them in the 4th century CE.

The Sasanids saw themselves as the successors of the Achaemenid Persians, but in reality, their power was tenuous. Vassals ruled remote areas, disunifying political power and leaving a way open for challengers. Several coinage findings imply, for instance, that the Kushano-Sasanians attempted to rebel. The degree to which this succeeded is not fully known. Losses against the Roman Empire, other revolts, and plunders by northern Arabs complicated the Sasanian circumstances additionally.

Further Nomadic Incursions from the North

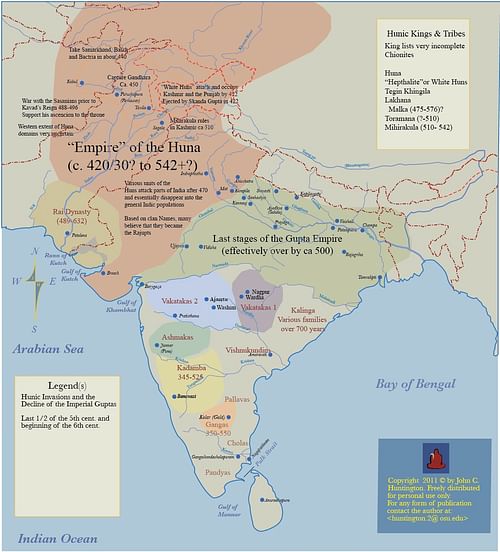

All these challenges shaped the rule of Shapur II (r. 309-379 CE), who achieved significant successes against the Arabs and Romans. He also aimed to firmly secure his empire's control over the regions of the Kushano-Sasanians. The rise of new nomadic incursions complicated the last goal. From 350 CE onwards, numerous records mention attacks from the north towards the regions around Bactria. The nomadic invaders have various names in historical documents, such as Xionites, Kidarites, or Kidarite Huns. However, the available records of their origins and whether those tribes are identical or distinct are unclear.

Generally, the term Kidarites most commonly relates to those nomadic people. Their relations with the Sasanians were complicated, considering they initially varied between being enemies and allies. According to Chinese records, the Kidarites established their domain in Balkh by the mid or end of the 4th century CE, replacing the Kushano-Sasanians.

Next to the Kidarites, other tribal people entered the stage of Afghanistan's history between the 4th and 6th century CE. Again, the available evidence via coinage, scriptures, and written records leaves an unclear picture. Some sources indicate that the Kidarites consolidated their power in Afghanistan, moved southeast toward India, and came into conflict with the Guptas. Others speculate that nomadic people called the Alchon Huns chased them in this direction by gaining control over the regions around Balkh and Kabul.

The Hephthalites

Another group of tribal people with particular importance were the Hephthalites, sometimes referred to as White Huns. They entered the stage of Afghanistan's history in c. 442 CE. After initial conflicts with the Sasanians, it appears they formed a temporary alliance. Peroz I (r. 459–484) allegedly relied heavily on the support of the Hephthalites to emerge as the winner of internal Sasanian power struggles. Additionally, this alliance played a vital role in recapturing the former provinces of the Kushano-Sasanians from the ruling nomadic people.

By 467 CE, most of the lost regions were back under Sasanian control. The Hephthalites themselves gained land as a reward for their support. But this was seemingly insufficient, as open conflict emerged a few years later between the former allies. After a decade of warfare, the White Huns dealt a crushing blow to the Sasanians in the Battle of Herat in 484 CE. This decisive victory led to the near destruction of the Sasanian forces and the death of Peroz I.

The Hephthalites plundered and subjugated large parts of the eastern Sasanian domain in the following years. According to some sources, another tribal people, the Nezak Huns, used this opportunity to settle in the area of Zabulistan in southern Afghanistan. Large parts of Afghanistan were now in the firm hands of nomadic tribes, pushing even further towards India and challenging the Guptas. But contrary to previous rulers, the Hephtalities seemingly had only a limited impact on the region's culture.

The end of the Hephthalites' rule came from the combined forces of a revitalized old foe and a new group of steppe people. The Sasanian Empire had regained strength and confidence by the middle of the 6th century CE, following successful conflicts with the Byzantines. North of the Oxus river, they found an ally in the First Turkic Khaganate, established by the nomadic Goktürks.

Their combined forces dealt a crushing blow to the Hephthalites. Consequently, the latter's regions north of the Oxus river went to the Goktürks. The territory in the south moved back under Sasanian control. The remaining Hephthalites splintered into smaller kingdoms and could never again exert dominance in Afghanistan.

Cultural Developments Through The Centuries

Knowledge about cultural developments before written records remains sparse. Various findings imply trade with neighboring cultures, such as the Harrapans. Afghanistan's mineral-rich regions allowed the exchange of materials like gold, silver, copper, and lapis lazuli for grains, cotton, or similar products. Later cultures, such as the BMAC, showed extensive artistry and metalworking skills via the production of intricate figurines and painted pottery.

Writing usage occurred from the Persian rule onwards. Yet, it is suspected to have ensued even earlier. The Achaemenids also implemented variously managerial aspects into their dominions, such as a tax system, legal reforms, and division of administrative zones. Arts and architecture showed a unique blend of Iranian legacy and cultures under Persian rule.

Hellenistic culture played a significant role in Afghanistan's ancient history after the conquests of Alexander. Multiple civilizations incorporated the Greek language, scripture, and coinage until long after the decline of Hellenic power. Examples are the Kandahar Greek Edicts of Ashoka (teaching moral precepts) and the presentation of Buddhist topics in Greco-Roman style in the northern Indian subcontinent. Hellenic-styled coinage was still in use much later, for example, by the Kushans and Hephthalites.

Greek architecture spread far as well due to rapid urbanization efforts. Until today you can find ruins of classical Hellenic buildings and styles, such as the iconic Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns. Especially within the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms, Oriental and Indian influences blended in. A prime example is the city of Ai-Khanoum. Its remnants feature buildings in classic Hellenic styles, such as a gymnasium, theater, or multiple temples. The Royal Palace instead shows a distinct combination of Persian and Greek architecture.

Upcoming cultural developments often resulted from synthesizing Hellenic and different local elements. The Parthians, for instance, continued the coinage tradition of the previous dominant powers and reused many existing buildings but brought their unique contribution to other parts of daily life. Clothing, architecture, and arts bore evident marks of their nomadic origins. Naturally, horse culture played an essential role within their empire. The breeding of superior horses was not just a sign of power for the elite but crucial for the military might of the Parthian army.

During the reign of the Kushans, a stunning cultural variety prevailed, not just regarding the practiced religions. In their realm, Graeco-Roman artistry existed next to pieces with clear (Western) Asian influences. Opulent jewelry and decorations, as did fine-crafted metalware, ceramics, and textiles, showed social status. Thanks to a general liberal mindset and the location at essential trade routes, the empire also fostered the development of various philosophical and scientific advancements.

This patronage continued into the Sasanian rule. On top, the Sasanians saw the revival of Persian culture as their highest duty. The combination of Achaemenid features with Parthian and Hellenic elements is a distinguishing hallmark of Sasanian art. Colorful adornments were prevalent in textiles, paintings, and other craftworks. Especially fabrics and carpets belonged to the most admired Sasanian products. Many of these aspects would later deliver a fundamental basis for Muslim artistry.

Outlook

By the mid of the 6th century CE, turbulent times have passed in contemporary Afghanistan. The impact of the Indo-European nomads seemed broken, and the Sasanians were back in control. But less than 100 years later, one of the most crucial developments would occur. Armed with weapons and unwavering faith, the early Arabs became the dominant power. Thanks to their influence, the teachings of the prophet Mohammed spread, making Islam the dominant religion of Afghanistan until today.