The Retreat from Kabul in 1842 was one of the most notorious disasters in the history of the British Empire. An East India Company army had invaded Afghanistan but was obliged to withdraw. This army of 4,500 soldiers and 12,000 camp followers was utterly destroyed before it reached the frontier, and the debacle condemned Britain to defeat in the First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-42).

Afghanistan & the Great Game

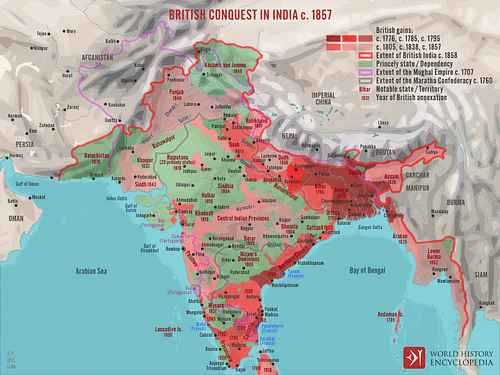

In the first half of the 19th century, the British government became almost obsessed with the idea that Russia harboured dangerous intentions towards its empire in the subcontinent. The Russian Empire did indeed seek to expand its influence beyond Central Asia through its client state Persia, but whether or not it really wished to invade India is a much-debated point. Afghanistan, sitting between Persia and British India, became a pawn in what became known as the Great Game between Britain and Russia. Both sides attempted to exert influence over the Emirate of Afghanistan without provoking their rival into a direct conflict. By 1838, the British were convinced that Russia intended to take over Afghanistan and the crucial Khyber Pass trade route. Consequently, the EIC Governor-General, Lord Aukland (1784-1849), announced his intention to invade Afghanistan, remove the Emir Dost Mohammad (1793-1863), and establish a British-friendly puppet ruler, Shah Shuja, the former Afghan king (r. 1803-1809). So began the First Anglo-Afghan War.

A British army of 21,000 men marched into Afghanistan, but with no unified opposition from the various Afghan tribal leaders, logistics proved to be the biggest threat to the invaders. In July 1839, the fortress of Ghazni was taken, and much-needed supplies were acquired. The EIC army then managed to take Kabul in August, but the British had badly overestimated local support for Shah Shuja and the new regime was far from popular.

The British occupiers tried to use bribes to exploit the age-old factions between the various Afghan tribes, which proved ineffective in the long term. The military coup and subsequent occupation, the unpopularity of Shah Shuja, Aukland's reforms in Afghanistan like the decision to reduce subsidies paid to local tribes, and anger at the fraternization between British soldiers and Afghan women, all combined to create the volatile conditions which led to a popular uprising and out-and-out war in 1841. The Afghan tribal leaders were still not at all united, but they at least had a common goal: kick the British out of Afghanistan.

Crisis

The crisis came in November 1841 when a mob murdered Alexander Burnes, an important political officer of the East India Company. The unrest quickly spread to outlying British garrisons. In Kabul, the lack of a decisive response to the unrest from the British commander Major-General William Elphinstone (1782-1842) only led to the situation worsening as more and more tribal leaders grew in confidence and entered the fray. The EIC army was permanently camped outside Kabul, but its defences were poor and vulnerable to the Afghan cannons and snipers hidden in the hills overlooking the camp. The number of Afghans in the hills was swelling by the day as soldiers came to Kabul from outlying towns. A breakout by the British from their camp was easily pushed back under heavy fire.

The British made the situation worse for themselves through a series of blunders and miscommunications between officers. The most serious decision was to store all of the army's supplies in the same fort, which was then captured by the Afghans. Low on supplies of ammunition and food (down to three days of rations only), with 600 men sick and wounded, and with little prospect of any EIC relief column coming to their aid from India, the British army was forced to negotiate a withdrawal from Kabul in December. Some Afghan leaders wanted the British to disarm completely before leaving the city. During this wrangling of terms on 23 December, Sir William Macnaughten (1793-1841), the EIC envoy to Kabul was murdered by Akbar Khan (1816-1845), the son of Dost Mohammad. Akbar Khan had tricked Macnaughten and only wanted to show him up for his double-dealing and attempted bribery of Afghan leaders. Macnaughten was shot with the very pistol he had only recently presented to Akbar Khan. Clearly, the British position was a desperate one. To add to their woes, the winter weather was bleak, and heavy snow was falling in Kabul and in the passes the EIC army would have to negotiate to reach the safety of India.

On 1 January 1842, the Afghan leaders agreed to permit a peaceful withdrawal of the British army and its attendants from Afghan territory. Other British garrisons besides Kabul were also to be abandoned. To ensure the withdrawal was peaceful, four British officers were taken hostage. Another reference to peace and "friendship and goodwill" was explicitly mentioned in the written withdrawal agreement. These handsome sentiments were not respected by either side in the events that followed.

The Race to Jalalabad

The retreating army, which left Kabul on 6 January, was composed of 4,500 soldiers (700 Europeans and 3,800 sepoys) and 12,000 camp followers. They were headed for Jalalabad 90 miles (144 km) away, but problems began almost immediately. The camp followers were particularly difficult to organise, and the column soon became dispersed. Lieutenant Vincent Eyre noted ruefully:

A mingled mob of soldiers, camp-followers, and baggage cattle, preserving not even the faintest semblance of that regularity and discipline on which depended our only chance of escape from the dangers which threatened us.

(Holmes, 56)

There were initially two distinct groups and a rearguard, but this arrangement soon lost shape. Crossing rivers was a nightmare. The Kabul River was intended to be crossed using a temporary bridge supported by submerged gun waggons, but it was not made ready in time, and the camp followers crossed wherever they thought they could.

There were far worse problems than logistics, though. As it turned out, despite the peaceful wishes of the withdrawal treaty, the more aggressive of the Afghan leaders got their way and consistently attacked the rear of the British column as it departed the country. The Afghans were armed with the long-barrelled match- or flintlock musket known as the jezail. The jezail had a distinctive curved stock, which allowed more accurate fire from a horse. The musket had a far longer range and was more accurate than any musket the British had in this period. Snipers concealed in rocky hilltop positions, in particular, proved a deadly menace to the enemy. An attack in the Khord Kabul Pass on 8 January reduced the retreating army by 3,000.

In the chaotic withdrawal, camels and supplies were taken by raiding cavalry, and on 9 January, 12 wives and 22 children of British officers were taken hostage (although Akbar Khan claimed they were taken away for their own safety). One of these, Lady Sale, survived her nine-month ordeal to write a bestselling diary of her captivity, and she became known as the 'grenadier in petticoats'. The British had no tents and very few supplies as they continued to cross rivers and the inhospitable terrain. Hypothermia claimed many lives. Guns were abandoned as horses became too weak to transport them, and many of the camp followers abandoned their loads, blocking the way through the narrow gorges for those coming behind them.

By 10 January, after another major attack in the Tunghee Tereekee Pass, there were only around 4,000 survivors from the original 16,500 that had departed Kabul. The dwindling force now had only one small cannon. Akhbar Khan sent an offer to allow the crushed army to retreat in peace if it left behind all of its weapons, but Elphinstone refused it.

On 11 January, the advance party of the British column was attacked when it reached the Jagdalak Pass (aka Jugdulluk). Lieutenant Eyre gives the following description of a typical ambush on the slow and disorderly column:

Fresh numbers fell with every volley, and the gorge was soon choked with the dead and dying; the unfortunate sepoys, seeing no means of escape, and driven to utter desperation, cast away their arms and accoutrements…and along with the camp followers, fled for their lives. (Holmes, 57)

On 12 January, Elphinstone was taken hostage when he naively attended a conference with Akbar Khan to negotiate some sort of ceasefire; the general later died of dysentery. What was left of the fleeing army now had to negotiate the Jagdalak Pass which the Afghans had blocked using holly branches. Only around 200 survived the passage through the pass as the Afghan snipers rained down their deadly fire. One sepoy, Subedar Sita Ram, noted: "We were attacked in front, in the rear, and from the tops of hills. In truth it was hell itself." (Macrory, 80)

The Last Stand

With only around 80 men of the HM's 44th Regiment left to fight, a pathetic last stand was made on 13 January on Gandamak Hill just outside the village of that name. This small group, which had only 20 muskets and two rounds of ammunition between them, refused the order to lay down their arms and was all but wiped out with sniper fire. Eyre describes this last, desperate stand:

The enemy, taking up their post on an opposite hill, marked off man after man, officer after officer, with unerring aim. Parties of Afghans rushed in an intervals to complete the work of extermination, but were as often driven back by that handful of invincibles. At length, nearly all being wounded more or less, a final onset on the enemy sword in hand terminated the unequal struggle.

(Holmes, 57)

Only Captain Souter and three or four others survived since the Afghans took them prisoner. Souter was taken because the Afghans thought he was an important individual from his colourful waistcoat, actually the regimental colours he had wrapped around his waist. The colours eventually found their way to the parish church at Alverstoke in Hampshire, England, and from there to the Essex Regiment chapel at Warley – a piece of the flag can still be seen there today.

Twelve cavalry riders made it away from the killing ground of Gandamak Hill, but these were picked off, and so only one European survived the retreat from Kabul to arrive at Jalalabad: a Dr William Brydon, who made it to safety on a lame pony. Brydon's approach to the British-held fort was spied through a telescope on the battlements:

As he got nearer, it was distinctly seen that he wore European clothes and was mounted on a travel-stained yaboo [Afghan pony], which he was urging on with all the speed of which it yet remained master…He was covered with slight cuts and contusions, and dreadfully exhausted…the recital of Dr Brydon filled all hearers with horror, grief and indignation. (Holmes, 57)

A number of sepoys also made it through and some of the stragglers amongst the camp followers. The retreat and destruction of an entire army was one of the worst military disasters in the history of the British Empire. Meanwhile, Shah Shuja was assassinated in April 1842. The British occupation of Afghanistan was at an end.

Revenge & Aftermath

The new Conservative government in Britain led by Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850) was determined to end the British meddling in Afghanistan but not before the experienced and meticulous Major-General George Pollock (1786-1872) was tasked with leading a face-saving attack on Kabul. Pollock had learnt valuable lessons on mountain warfare during the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814-16), and he became the first general in history to successfully lead an army through the Khyber Pass in April 1842. This army, known as the Army of Retribution, defeated Akbar Khan at Tezin and reached Kabul in September 1842, where the surviving British hostages were released – 10 women, 11 children, ad 85 soldiers. On 9 October, in a symbolic act of vengeance, the British blew up the city's Great Bazaar. A round of revenge attacks, rapes, and plunder followed. Three days later, the British army marched out of Afghanistan and retraversed the Khyber Pass.

Back in Britain, there was an official inquiry into the retreat debacle, but little came of it. Major Pottinger, a senior political officer at the time in Kabul, was exonerated from any stain on his conduct, and Elphinstone's second-in-command, Brigadier Shelton, was court-martialed but ultimately found not guilty of any incompetence. A proposal in Parliament by the Conservatives to censure the previous Whig government's sponsorship of the initial campaign came to nought since both major political parties had agreed to it at the time. In politics, as in the art and literature of the period, Pollock's successful march to Kabul was played up, and Elphinstone's disastrous retreat was played down as one of those unfortunate consequences of empire-building.

In Afghanistan, it was now clear that neither the British nor a puppet emir could rule without the consent of the local militant tribal leaders. Accordingly, Dost Mohammad was restored to power in 1843, and the Afghan tribes were permitted to live as they had always done. As neither the Russians nor the British could control such a hostile region, the British settled for a policy of containment, one which became known as 'masterly inactivity'. Instead, the British turned their attention to the Sikh Empire and won both the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-6) and the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9) to take over yet another large slice of the Indian subcontinent. The British never gave up on the dream of controlling Afghanistan, and so there followed the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-80) and the Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919). The Great Game of empires continued into the 20th century, but Afghanistan remained independent of both Russia and Britain.