The British East India Company (1600-1874) was the largest and most successful private enterprise ever created. All-powerful wherever it colonised, the EIC's use of its own private army and increasing territorial control, particularly in India, meant that it faced ever-greater scrutiny from the British government in the late 18th century. Restricted by several successive acts of Parliament over many decades because of allegations of corruption and unaccountability, the EIC's independence ended with the chaos of the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857-8. The British Crown replaced the EIC's board of directors as the rulers of British India, and Parliament officially dissolved the EIC in 1874.

A Trade Giant

Founded in 1600 by royal charter, the East India Company was established as a joint-stock trading company to exploit opportunities east of the Cape of Good Hope where it was granted a trade monopoly. Crucially, to conduct this trade, the EIC was permitted to 'wage war'. Although the EIC did not hold sovereignty in its areas of operation, it was permitted to exercise sovereignty in the name of the English (and then British) Crown and government. This subtle distinction became even more blurred as the company became more powerful, and therein lay the problem and the source of its ultimate demise.

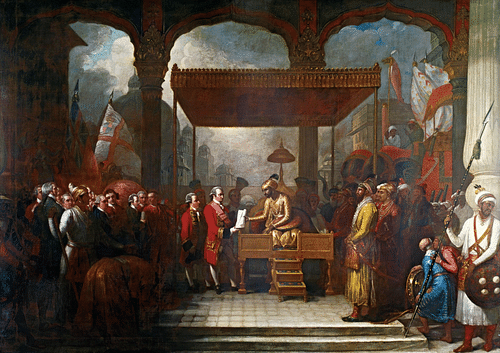

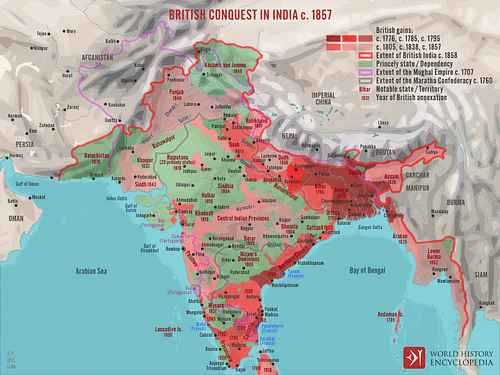

The company made a fortune for its shareholders from its global trade in spices, tea, textiles, and opium. In order to protect its interests, the EIC paid for its own private armies in India, headquartered in Bengal, Madras, and Bombay (Mumbai). It also hired out on a long-term basis regiments of the regular British Army. From the mid-18th century, starting with Robert Clive's victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, these forces allowed the EIC to take over territory from the decaying Mughal Empire and Indian princely states. The EIC then administered these territories, extracting taxes and duties to further enrich its shareholders and maintain its armed forces.

Increasing Criticism

The EIC had many enemies, not only rival European trading companies and rulers in India but also back in Britain. It was criticised for its monopolies, harsh trading terms, and corruption. The company's trade was so large it was responsible for a serious drain of Britain's stock of silver. Its directors returned to England with vast new wealth that upset the established hierarchy of British society. This nouveau riche was disparagingly called 'nabobs' (from the Indian term nawab for ruler). The EIC was not popular for the damage it did to the English wool trade through its cheap imports of Indian-made textiles. Later, Indians would be equally disturbed by the import to India of even cheaper cotton cloth manufactured by the large mills of industrialised England. Finally but by no means least, the EIC swept away rulers that stood in its path, relentlessly siphoned off resources, and was not doing enough (or anything) to spread Christianity amongst the peoples living within its vast territories.

In effect, the EIC was a state within a state, now even collecting its own taxes and dispensing justice through its courts. It was an entity with sovereign powers, but one which was not accountable for its actions to anyone but its shareholders. As the celebrated Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith (1723-1790) noted in his An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, a sovereign that was holding a trade monopoly could not possibly rule with fairness to all its subjects, the two ideas were simply not compatible. Parliament, although with over 100 members actually in the employ of the EIC at one point, was also raising uncomfortable questions: Was the EIC suitably representing British interests abroad? Did its trade monopoly not infringe upon the potential growth of other British companies?

Increasing Regulation

1773 Regulating Act

One of the first ominous signs for the EIC directors that their long process of enrichment might be coming to an end involved the return of Robert Clive (1725-1774) to England. With rumours rife that the former Governor of Bengal's vast riches had largely been gained through corruption, Parliament set up an inquiry into Clive's affairs in 1773. In the end, Clive was honourably acquitted, but his advice to Parliament to take over the EIC was not heeded. There was, though, a restructuring of the management of the company. The 1773 Regulating Act resulted in changes. The leverage acted upon by the government was that the EIC needed a loan despite the fact it had just awarded its shareholders a 12.5% dividend. There was the appointment of the first Governor-General of the EIC, Warren Hastings (1732-1818), who now governed with a board of four advisors. Additional restrictions are here summarised by M. Mansingh:

The Court of Directors in London was required to hold elections every four years, with one-fourth of its membership replaced annually, and shareholders of £1,000 or more stock entitled to vote. Further, the Directors were required to submit copies of all correspondence to and dispatches from their factors [traders] in India to a Minister of the Crown, that is the Secretary of State for India…A Supreme Court was established in Calcutta with appeals only to the King in Council.

(354)

The British government had at least gained some influence on the military, financial, and political decisions in the territories administered in its name by the EIC. The greater interest the British government began to take in India was likely a direct result of the loss of its colonies in North America in 1783.

Hastings was specifically charged with reducing corruption, mostly the convention of traders indulging in private trade and accepting bribes from future contract holders. All private trade by EIC employees was prohibited, and salaries were increased. Hastings also attempted to stop the worst of the abuses carried out by local EIC agents on indigenous peoples.

Rather ironically given his original brief, Hastings was himself investigated for corruption when he returned to England in 1785. The Whig politician Edmund Burke (1729-1797) was particularly scathing of what he regarded as yet another 'nabob'. Even worse in Burke's eyes, Hastings had sullied the name of Britain in India and on the international stage by stealing on a grand scale and acquiring for the EIC "all the landed property of Bengal upon strange pretences" (Wilson, 132). Once again, prominent members of the British Parliament were aghast at lurid tales of the EIC's policies in India, and many sought to bring the company under much greater scrutiny and control. Reform was not straightforward, though, when dealing with such a commercial giant. Many MPs remained in EIC employ or were shareholders (23% in the 1770s). Further, the British monarchy was not in favour of infringing on private property. Still, the burning question of the day was why was this private company with private interests being allowed to conduct itself like a state but without any of the constraints of an electorate or any of the scruples of justice. The atmosphere of the time was relevant here. Political philosophers were now influencing politicians in Britain with their thoughts on the importance of individual liberty, government by consent, and rule through justice.

1784 India Act

The 1784 India Act (often called 'Pitt's India Act' after the then prime minister William Pitt the Younger, 1759-1806) did restructure the top management of the EIC once again, and Parliament installed one of its representatives on the now all-powerful Board of Control based in London. The India Act stipulated that the Board of Control "superintend, direct, and controul all acts, operations, and concerns, which in any wise relate to the civil or military government or revenues of the British territorial possessions in the East Indies" (Barrow, 63). For the moment, government interference remained largely limited to oversight rather than regular intervention, but the cumbersome bindings of red bureaucratic tape were growing ever tighter on the liberties long taken by the EIC.

In 1787, Hastings was impeached by Parliament and charged with "high crimes and misdemeanours." The case was heard in Westminster Hall under the auspices of the House of Commons, and the public and press could attend. Just like Clive, Hastings was ultimately acquitted of any wrongdoing during his time in India. This time, though, the dark affairs of the EIC had come under a very bright and public spotlight of scrutiny.

1813 Charter Act

The next wave of regulation came with the Charter Act of 1813. From now on, any new territory captured by the EIC would come under the direct sovereignty of the British Parliament. In addition, the EIC's trade monopoly in India was ended, and it had to end its ban on missionaries in its territory (although they required a license to operate). Further control came following the global economic crash of 1825. The EIC got itself into financial difficulties and required a bail-out from the British government. The loan was forthcoming, but the catch was further regulation of EIC affairs. MPs were considering yet more drastic action against the EIC:

The broad questions before Parliament were whether the Company should continue to exist, whether it should retain its monopoly of trade to China, and what the role the Company should play if allowed to continue to exist but without its monopoly. (Barrow, 110).

As one MP, Mr James Silk Buckingham, noted in 1830, "The idea of consigning over to a joint stock association …the political administration of an Empire peopled with 100 million souls… [was] preposterous" (Dalrymple, 390).

1833 Charter Act

The 1833 Charter Act further tightened the noose around the neck of the EIC. The Act removed all limitations the EIC had set on immigration to India. The company's monopoly on trade with China also came to an end. The judicial system – woefully behind in terms of cases being heard – was centralised and future regular issues of new codes attempted to homogenise the laws and their application in India. Perhaps most importantly, this charter enlarged the ruling Council and gave it and the Governor-General the power to create legislation applicable to everyone resident in EIC territory. In 1835, for the first time, the Company issued a coinage that was legal tender in all its presidencies (administrative regions) and in the Indian princely states.

The new Company coin symbolically established the British - not just the Company - as the dominant power in India and created one of the conditions for the emergence of a national economy…it could be said that the unveiling of the Company rupee was also the unveiling of the colonial state. (Barrow, 113-14)

The coins carried a portrait of King William IV of the United Kingdom (r. 1830-1837).

1853 Charter Act

The 1853 Charter Act reduced the EIC's powers again so that the EIC was "now nothing more than a managing agency for the administration of India subject to the British government's direction in matters of policy" (Spears, 148). The great trading company was very much like a British colonial administration elsewhere in all but name. It could raise taxes, had an army and a vast civil service, all connected monetarily by its coinage and physically by a network of railway and telegraph lines. Further, the very idea that Britain was both in charge of and responsible for India had become an accepted one in the minds of colonial administrators and the British Parliament. It had been a long and progressive process to reign in the EIC, but the final closure came in one climatic and bloody disaster.

The Mutiny & Crash

In 1857, the EIC was rocked by the Sepoy Mutiny (aka The Uprising or First Indian War of Independence), which started with Indian soldiers (sepoys) in the EIC army rebelling against their officers. The unrest quickly spread to involve several princely state rulers and Indians of all classes. The causes of the rebellion were many and ranged from discrimination against Indian cultural practices to Indian princes not being allowed to pass on their territories to an adopted son, but the initial spark came from the sepoys. Sepoys protested against (amongst other things) their much lower pay compared to British EIC soldiers. At this point, the EIC employed around 45,000 British soldiers and over 230,000 sepoys. The sepoys took over important centres like Delhi, but their lack of overall command and coordination meant they could not win against the superior resources of the EIC, especially when 40,000 troops were shipped into India by the British government.

After the mutiny was quashed, the sentiment in Britain was that such an important colony as India could no longer be left in the hands of a private company. The general mood was captured by the Illustrated London News in the following article extract of July 1857:

The state of affairs in India may well exercise the alarm of the nation…Our house in India is on fire. We are not insured. To lose that house would be to lose power, prestige, and character – to descend in the rank of nations…Whether it were desirable that we should win India by the sword is no longer a question. Having won it we must keep it. (Barrow, 167-8)

The British Crown took full possession of EIC territories in India with the Government of India Act of 2 August 1858. The EIC armies were absorbed into the British Army, and the EIC navy was disbanded. The most aggressive and utterly ruthless private company ever yet created was effectively nationalised. So began what is popularly termed the British Raj (rule) in India. A new Secretary of State for India was appointed and made responsible directly to Parliament, while a Viceroy represented the Crown. The Viceroy led a cabinet of ministers, and they collectively supervised the daily administration and judicial operations. India was divided into governorships, which were in turn split into deputy governorships. On 1 June 1874, after generously allowing its shareholders to reap yet more dividends for 16 years, Parliament formally dissolved the EIC. In 1877, Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India. The East India Company was no more.