The Battle of Plassey on 23 June 1757 saw Robert Clive's East India Company army defeat a larger force of the Nawab of Bengal. Victory brought the Company new wealth and marked the beginning of its territorial expansion in the subcontinent. Not much more than a skirmish, Plassey has often been cited as the beginning of British rule in India.

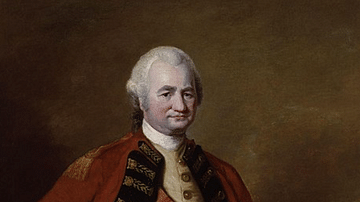

Clive & the Expansion of the EIC

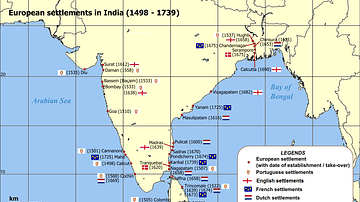

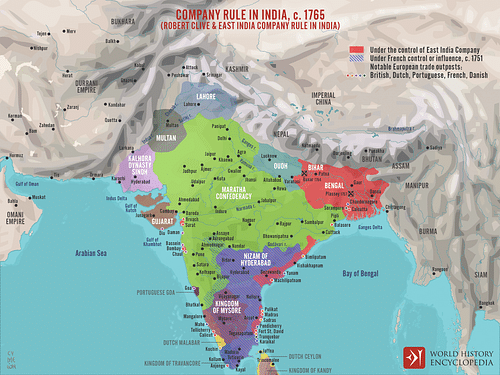

The East India Company (EIC) was founded in 1600, and by the mid-18th century, it was benefiting from its trade monopoly in India to make its shareholders immensely rich. The Company was effectively the colonial arm of the British government in India, but it protected its interests using its own private army and hired troops from the regular British army. By the 1750s, the Company was keen to expand its trade network and begin a more active territorial control in the subcontinent.

Robert Clive (1725-1774) had already distinguished himself in the Company service at Arcot in August 1751 where he had led his troops to withstand a 52-day siege. This was followed by a victory at Arni in December 1751. Clive then commanded the EIC artillery at Trichinopoly in June 1752. By 1755, Clive was a lieutenant colonel in the EIC army, and his name was under consideration to become the next Governor of Madras, but Bengal was the real trouble spot for the East India Company.

There was a new ruler of Bengal, Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah (b. 1733). Only assuming the role in April 1756, Siraj ud-Daulah, was in his early twenties and was something of a reckless youth. He was a surprising choice to inherit the nawab role from his grandfather Ali Vardi Khan. The decision to make Siraj ud-Daualah the crown prince four years earlier had already split the Bengal royal court just when unity was required to face its greatest challenge.

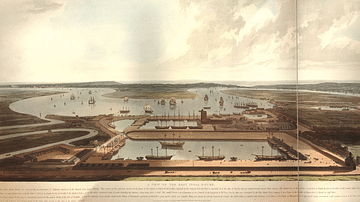

The new nawab took exception to the EIC presence in the region and marched on Calcutta in June 1756. Siraj ud-Daualah was particularly angry that the EIC had added to the fortifications of Calcutta without permission and had not responded favourably to his request to remove them. Arriving in the city with his army, a short siege followed, and Calcutta fell. The EIC was already obliged to respond to the loss of one of its most important trading centres but a curious incident then occurred which stiffened the resolve of the militarists in the Company and weakened the position of those who wished for the EIC to remain a purely trading body. After the fall of Calcutta, a number of military personnel and civilians who had been in the city's fort were taken prisoner and held in a small, poorly lit, and badly ventilated prison cell locally known as the Black Hole of Calcutta. According to one prisoner, only 23 men of the original 146 male and female prisoners survived the confinement, all the others died of extreme dehydration in the terrible heat of the packed cell. The effect of the Black Hole story was to galvanise the military response from the EIC.

Robert Clive was dispatched with an army to re-establish the EIC's trading presence in Calcutta. Sailing in five ships and with an army of some 1,500 men, Clive succeeded in recapturing Calcutta in January 1757, but Siraj ud-Daulah still had a massive army at large. What is more, the rival French East India Company was in control of Chandernagore just up the coast. Clive was determined on a decisive military action. He captured the fort of Hughli later in January, which was then destroyed by cannon fire from the EIC fleet. An attack on the nawab's army outside Calcutta was less successful and obliged Clive to retreat. Both sides became wary of the other and the heavy casualties any future confrontation would bring, but the control of Bengal was now at stake. A peace treaty was agreed upon, although both sides knew this was but a temporary pause. In the interim, Clive could now deal with the threatening French presence in the region. In March 1757, Clive attacked and captured Chandernagore, bringing an end to any remaining ambitions the French had in Bengal. When the Hindu Seths of Murshidabad, a dynasty of financiers worried at the demise in European trade any wider conflict would bring, withdrew their support of the now isolated nawab, Clive seized the moment.

Battle Formations

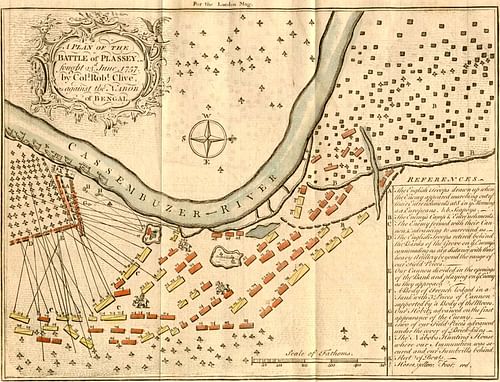

The Battle of Plassey took place near a village of that name on the banks of the Bhagirathi river in Bengal on 23 June 1757. Clive had first taken the fort of Katwa a few days before, which was packed with very useful food supplies. After capturing Katwa and the nearby town, Clive was unsure how to proceed. The weather was abysmal as the monsoon season got underway, and he had no cavalry, but if he did not cross the river, soon it would be in flood and too wide and deep to cross. He put the situation to a war council, but his commanders were split over the choice of retreating and awaiting better conditions or pressing forward into battle. Clive withdrew to ponder the situation further and, after about an hour, took the fateful decision to press on with the attack.

Marching on through rain and mud, Clive established his command post in a hunting lodge by a mangrove swamp. This partially submerged grove was a better redoubt than it sounds: Clive's army was now well-protected on two sides by an old wall and a high bank in front of a long ditch. The two armies were literally within earshot of each other. From the roof of the hunting lodge, Clive could see the enemy ranks, which he described as follows:

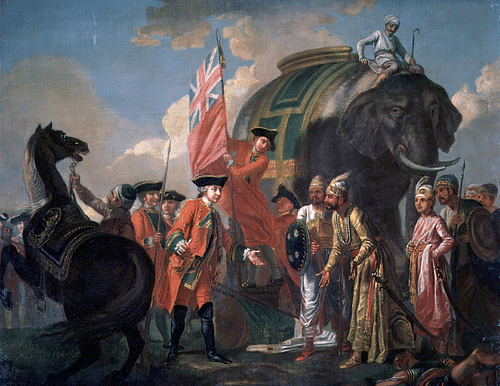

What with the number of elephants, all covered in scarlet embroidery; their horses with their drawn swords glittering in the sun; their heavy cannon drawn by vast trains of oxen; and their standards flying, they made a pompous and fabulous sight.

(Dalrymple, 126-7)

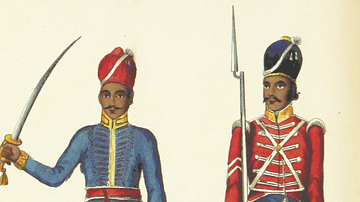

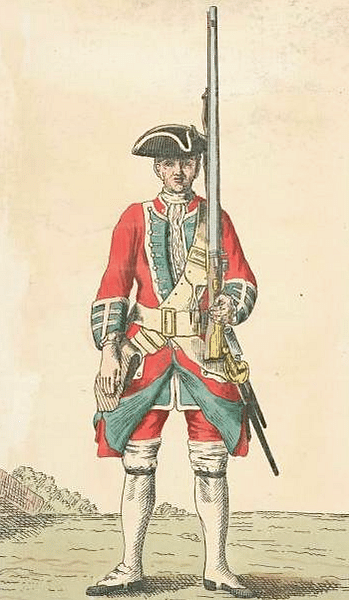

Clive commanded an army composed of 1,400 sepoys (Indian troops) and over 700 Europeans (infantry plus gunners), including some 250 battle-hardened members of the British Army's 39th Foot Regiment. Some historians would put the total army at 3,000, but this figure includes the sailors of the five ships in Clive's original expedition to Bengal. The nawab's force was much larger, perhaps around 50,000 men. These were well-trained and included a small contingent of French gunners (around 50 men with four cannons), but the loyalty of the main army to the nawab, even of some of the commanders, was highly questionable. The typical weapons on both sides were flintlock rifles, swords, halberds, and lances. Clive had only 10 sizeable cannons at his disposal compared to the nawab's 51 (or 53 according to Clive himself).

Attack

The fighting began around 8:00 a.m. with the usual artillery barrage from both sides. It was at this point that one of the nawab's generals, Mir Jafar (1691-1765), sent word to Clive to confirm what he had previously promised: he would not fight for the nawab. Unfortunately, Clive's cannons had already been busy bombarding the very section of the battlefield Jafar's troops were stationed. Then a heavy downpour tipped the scales. The nawab's cannons had not been protected, but Clive's gunners wisely used tarpaulins to keep their powder dry. When the storm ended, the nawab, probably thinking Clive's cannons were also out of action, sent in his cavalry. The British artillery then opened up again and cut down the enemy horse, killing one of the nawab's few loyal commanders, Mir Madan. After a lull of a few hours, Clive was obliged to follow up an unordered advance by his second-in-command Kilpatrick – who had seen the far right flank of the enemy troops begin to withdraw – and so the British pressed home their advantage. At the sight of this carnage, most of the nawab's infantry began to leave the field in various groups.

The gunners of the nawab's army tried to get their cannons firing again, but they proved to be more of a hindrance than an aid, as here summarised by the historian Lawrence James:

They had massive twenty-four and thirty-two pounder pieces, each mounted on platforms dragged by forty or fifty yoke of bullocks and nudged into position by elephants. Their transport proved the gunner's undoing for three elephants were killed and the rest became 'unruly'. The oxen, too, were terrified by the fire and stampeded, taking their drivers with them. If this was not enough, one observer noticed that the Indian gunners seemed clumsy and once accidentally set alight their own powder barrels, which exploded and added to the pandemonium. (35).

Seeing the obvious lack of loyalty amongst his commanders, the nawab promptly withdrew on his camel. Clive's reserves pursued some of the retreating enemy in a chaotic and bloody melee that involved men, camels, and more panicking elephants. The battle – in the end more of a skirmish – was won by 5:00 p.m., with the British suffering a mere 50 fatalities and the nawab's army over 500 dead and wounded.

Aftermath

After the battle, the nawab was captured, executed (stabbed to death), and replaced by Mir Jafar. The enormous treasury of the ex-nawab was distributed amongst the victors, as was the norm, and Clive made himself vastly richer than he already was, acquiring what today would be over $50 million. A grateful Mir Jafar also gave Clive the lucrative rights to the annual rent revenues (jagir) around Calcutta. Clive was able to jubilantly report to the EIC directors in London that they now had the "power to be as great as you please in the kingdom of Bengal" (James, 36). A more realistic assessment of the Plassey victory is given by the revisionist historian Jon Wilson: "It merely ensured that political chaos endured in Bengal for longer than it would have done otherwise" (103). Whatever the realities on the actual field of battle and the immediate aftermath, Plassey was built up as a great victory at the time, chief amongst the propagandists being Clive himself who several times described the events at Plassey as nothing less than "a revolution". It is, too, significant that the 39th Foot Regiment (and its successors) thereafter carried badges on their uniforms with the words "Plassey" and "Primus in Indus".

The power vacuum after the victory at Plassey allowed the EIC to siphon off the resources of Bengal without paying the costs of administration, which were left to the puppet nawab. The battle also resulted in Clive becoming forever associated with the subcontinent and earned him the moniker 'Clive of India'. He was made the Governor of Bengal in February 1758, a post he held for two years, and he was reappointed in 1764. As the first move in a series of expansions of EIC territorial rule, Plassey and 1757 are often cited as the beginning of British rule in India, even if the process of colonialization was, in reality, more gradual. The idea that Plassey was a turning point became even more widely held in the Victorian era when commemorative statues of Clive were set up in London and Calcutta and school textbooks featured the battle prominently. Even for Indians, the date of Plassey remained significant. During the Sepoy Mutiny, the insurgent leader Nana Saheb Peshwa II (1824-1859) attacked the EIC residency at Cawnpore (Kanpur) 100 years later and on the very same date as that of the Battle of Plassey.