A sepoy was an Indian soldier in the armies of various states and European trading companies in the Indian subcontinent and then, from the second half of the 19th century, in the British Indian Army. Recruited from many different population and religious groups, sepoys came to dominate the British armed forces in the subcontinent, even if they were not permitted to become officers until the 20th century. The term sepoy continues to be used for ordinary infantry in several armies today.

Sepoy Armies

The term sepoy derives from a corruption of the Persian term sipahi, illustrating that it was the armies of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857) in India who first used these locally-recruited troops as musket-armed infantry. Although used by the French East India Company and many Indian princely states, sepoy soldiers, at least in the English language, have become most associated with British armies in the Indian subcontinent. They have also become most associated with infantrymen, and other terms are generally used for other types of soldiers such as sowars for Indian members of cavalry corps.

The EIC Army

The East India Company (EIC) gradually spread its grasping tentacles of control over many parts of India. The Company was founded in 1600, but it was not until the 1757 Battle of Plassey, when Robert Clive (1725-1774) defeated the army of the Nawab of Bengal, that the EIC really began to look like the colonial arm of the British Crown and government in the subcontinent. Eventually, by the mid-19th century, the EIC came to employ a private army of over 275,000 men. Of these, around 45,000 were British soldiers and over 230,000 were sepoys. First known as peons and then sepoys, Indians came to dominate the EIC army, but after 1765 they were not permitted to become officers. The change of name to sepoys reflected the different training and weapons Indian troops received in the fully professional EIC army as opposed to the early days when native recruits were merely groups of local mercenaries bearing whatever arms they could lay their hands on.

The EIC did not have a single army but rather allowed each of its presidencies (administrative regions) to raise its own force. This was because each trade centre was geographically isolated from the others. Examples of presidencies are Bombay (Mumbai), Madras (Chennai), and Bengal, each governed by a president (later to be called a governor). As each army was recruited and maintained in isolation, distinctive military traditions developed. The first professional sepoy units were created by Robert Clive in 1757, and, after Plassey, Clive formed the first sepoy battalion, the 1st Bengal Native Infantry, which had the nickname Lal Pultan or 'Red Battalion'. In 1758, two more sepoy battalions were created by the Madras presidency, and by 1768, the Bombay presidency had two sepoy battalions of its own. More battalions followed, and those who performed well in battle were sometimes given the honorary title "grenadier" in their battalion name. "Light infantry" was another honorific title, but it is not clear whether there was any practical significance to this in terms of weapons, training, or strategic use in battle.

Besides infantry, cavalry (from c. 1780), marine, and artillery sepoys, a vast number of Indians found other roles in the EIC armies. One large group was the labourers who assisted engineers in such projects as bridge and fortification construction, variously known as Sappers and Miners, Lascars, or Pioneers. Indians also acted as water carriers, baggage porters, cooks, and transporters of ammunition and cannonballs. There was, too, another group: Eurasians, that is soldiers with a mixed British/Indian or Portuguese/Indian parentage. These Eurasians were often called Topasses or 'hat-wearers' because many wore turbans as sepoys did.

Sepoys helped the EIC win huge swathes of territory and vast riches during a century of many wars, including the four Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-99), the three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1819), the Gurkha War (aka Anglo-Nepalese War, 1814-16), the three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824-85), and the two Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845-49). As the historian I. Barrow notes, "It is one of the great ironies of the Company's history that its Indian empire was effectively won by Indian troops" (82).

Recruitment

Sepoys were recruited locally by each EIC presidency. Although the EIC was not particularly generous in its pay for British or sepoy troops, there was the opportunity for extra income when stationed outside a soldier's home presidency, and some commanders shared out gains after a victory in battle or a successful siege. Sepoys, especially Hindus from peasant backgrounds, were also attracted by the chance to gain greater status in local society. A soldier was a highly-respected profession "which had always been honoured in Indian society, even if this involved, as it inevitably did, fighting against his own people…Soldiering carried with it dignity and offered a good livelihood and pension" (James, 131-2). This was so much so that sons and nephews of serving sepoys often joined the EIC army, too.

Local recruitment could lead to some problems as the Company expanded its territory to control new population groups. There was some tension between sepoys who followed different religions. High-caste Hindus were constrained by a religion which regarded Sikh and Muslim sepoys as untouchables. Expansion also meant new recruits even in 'frontier' areas not yet fully controlled by the EIC. In these regions it was not uncommon for the EIC army to form bands known as Local Infantry, often disparately armed mercenaries like those the Company had first started out with. A famous Local Infantry unit was the 1815 Sirmoor Battalion composed of Gurkhas, which had just three British senior officers. Such units, over time, might become full EIC companies, as happened with Sikh troops following the conquest of the Punjab in the mid-19th century. Sikh troops were first formed into the Frontier Brigade, then became the Sikh Local Infantry, then the Punjab Irregular Force, and finally the Punjab Infantry.

A third source of native troops was the armies of conquered or allied rulers of the Indian princely states. Such armies, or specific units within them, were often taken over and run by EIC officers. These allied units were known as Contingent Units, and some could be very large, such as the Gwalior Contingent which was composed of seven infantry battalions, two cavalry regiments, and an artillery unit.

Initially, sepoy troops were commanded by Indian officers known as subedars (captains) and jenadars (lieutenants), but into the 19th century, these were replaced by British-only commissioned officers. Sepoy sergeants (havildars) and other non-commissioned officers (NCOs) were responsible for instilling discipline in the troops and meting out the punishments ordered by their commanders. In the rather threadbare command structure of the EIC, a British captain led a sepoy battalion. In contrast, an all-British battalion, considered more prestigious, was commanded by a major. If a sepoy was court-martialled, his case was heard by Indian NCOs. Punishments included hanging in the case of murder and 500 lashes for looting. By leaving sepoy affairs to senior sepoys, the British officers saved themselves some work and perhaps the embarrassment of not understanding what their men were really up to. This distance – physical in camp, linguistic, and cultural – between British and Indians in the army would later backfire as a spirit of mutual distrust developed, often entirely unjustified but born from a distinct lack of contact between the two sides.

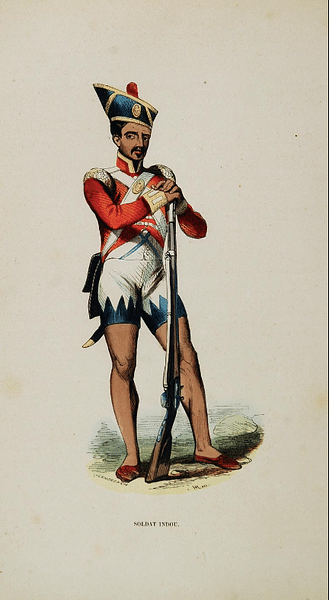

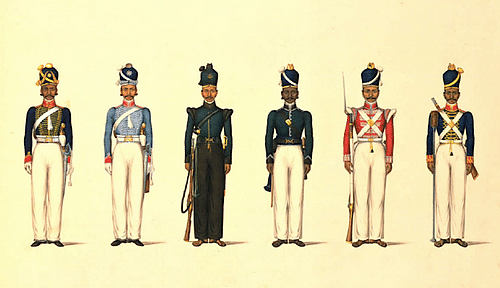

Uniforms

Sepoys wore similar red jackets to British EIC soldiers, but their coloured facings (e.g. lapels, collars, and cuffs) varied over time and place. Colours also changed with the regular reshuffling and renaming of battalions and regiments. Red, dark green, dark blue, grey, and khaki featured prominently in facings. These colours could also denote military function. Sepoys were distinguished by their jangheas (a type of shorts), alternatively, they wore longer trousers (jodhpurs) or baggier trousers (pantaloons), which were a badge of rank from 1801, but later all troops were allowed to wear them in hot weather. The trousers and shorts of regular sepoys were usually white with variously coloured trim. Another indicator of rank could be a coloured silk sash or cummerbund, as well as coloured lace additions to the hems of jackets, trousers, and shorts. Sepoy footwear was typically leather sandals or, from the late 19th century, boots.

Sepoys wore various types of turban, which could carry brass additions such as a front plate of identification, a pointed top or ball, and a decorative chin strap. An early turban type worn by Bengal sepoys was the 'sundial' turban, so called because the front leaf-shaped badge ended in a tall point. This badge, like many others, showed a sepoy's unit or function.

Bombay sepoys famously wore a turban with a brass plate shaped like a bishop's hat and a brass ball at the crown. A sergeant might wear some sort of identification of his rank on his turban such as a silver tassel. Royal Horse Artillery units had the most flamboyant turbans which were often covered in cheetah or leopard skin and sported a horse-hair mane.

After 1806, false turbans were worn, that is cloth stretched over a bamboo or rattan frame made to look like a turban. The first designs of these false turbans were so uncomfortable to wear and such a break with tradition there was even a brief sepoy mutiny in Vellore in 1808. While sepoy uniforms became less and less dissimilar to those of British troops, the turban in all its varieties remained the most obvious mark of distinction of a sepoy soldier. In the second half of the 19th century the Bengal and Bombay armies switched from turbans to a sort of forager or Kilmarnock cap.

In battle, sepoys were arranged in ranks so as to present a series of devastating volley-fire from muskets or rifles. They then charged the enemy with fixed bayonets. Some sepoys, particularly sergeants, might also carry a traditional tulwar sabre or a halberd. To achieve accuracy and discipline under fire, sepoys underwent rigorous training, and it was for this reason that young recruits were preferred so that they might more readily respect and obey their officers than older men.

Rebellion

Although sepoys were the backbone of the EIC army, this very reliance became a major weakness. As noted, there was a notable rebellion of sepoys in Vellore in southern India in July 1806. Short-lived, the mutiny still resulted in the deaths of over 100 British soldiers and officers. The sepoys, already unhappy with the new false turbans, had mutinied over suspicions and rumours that the EIC was intent on converting them to Christianity, as well as being unhappy with certain changes in regulations.

In 1857, the Sepoy Mutiny (aka Sepoy Rebellion, the Uprising, and the First Indian War of Independence) was a much bigger attack on British rule in India than Vellore. The mutiny began on 10 May when EIC sepoys protested in Meerut against their much lower pay compared to British EIC soldiers. In addition, sepoy wages had not been raised for over 50 years, meaning that in real terms their pay had lost half of its value since 1800. Indian soldiers were not happy either with the obligation to serve outside India (which would require some Hindus to perform costly rites of purification) or the institutional racism that prevented them from ever becoming officers. The final straw was the introduction of greased cartridges for Enfield rifles. Sepoys thought (incorrectly) that the animal fat grease was derived from pigs and cows, which offended Hindu and Muslim beliefs, especially since it was rumoured the cartridges had to be prepared by mouth, ripping open the paper packaging of the gunpowder only with one's teeth (also not true).

The initial spark that set off the sepoys was the punishment of one of their own, Mangal Pandey (aka Pande), in March 1857. Pandey had wounded a European EIC officer near Calcutta, and for his crime, he was executed. This was a matter of justice perhaps, but the outrage sprang from the decision to also flog Pandey's entire sepoy company. Then, on 10 May 1857, the EIC sepoys at Meerut raised arms. They protested the 10-year prison sentences handed down to 85 fellow sepoys for refusing to use greased Enfield cartridges. The mutineers killed their British officers and then went on a rampage. As one mutineer lamented: "I was a good sepoy, and would have gone anywhere for the service, but I could not forsake my religion" (James, 239). The mutineers captured nearby Delhi on 11 May, murdering European men, women, and children, as well as Indians who had converted to Christianity.

The mutiny quickly spread across Bengal where 45 of the 74 sepoy regiments rebelled. The Bengal cavalry regiments also mutinied. As a precaution, 24 of the remaining 29 sepoy regiments were disbanded or disarmed by the EIC. Fortunately for the British, in the EIC's other two main centres – Madras and Bombay – the former army remained loyal, and only two regiments rebelled in the latter.

The sepoy cause was taken up by a host of Indian princes disgruntled at their poor treatment by the EIC and by peasants and artisans who had suffered under EIC governance, principally from over-taxation and cheap imports. Although the rebellion spread to much of northern and central India and the sepoys took over several important centres, their lack of overall command and coordination and the far greater resources of the EIC and the British government led to their downfall. To fight the rebels, the regular British Army was used (shipped in fresh from Europe) along with loyal Sikh troops and new allies such as the Gurkhas from Nepal. The mutiny was quashed by the spring of 1858, but the number of casualties was high:

2,600 British enlisted soldiers and 157 officers were killed. Another 8,000 died of heatstroke and disease, while 3,000 were severely injured. Indian deaths from the war and the resulting famines may have reached 800,000.

(Barrow, 115)

The unrest led to the British government finally taking over EIC territories in India and ultimately dissolving the East India Company altogether.

Later History

By 1895, the EIC army had become the British Indian Army (or 'the Army in India'), and the British had halved the number of sepoys in their employ to around 120,000 men. The ratio of sepoys to British thereafter remained stable at around 2:1. There was also a marked preference for Indians from the northern part of the subcontinent as these were seen as being more loyal than those from the south. The British officers at least learnt their lesson from the Mutiny and now lived much closer lives with their troops, a policy which paid off handsomely with a real esprit de corps developing that was rarely seen in other parts of the British Empire where local troops were also widely used.

In addition, Indians could now be officers, known collectively as 'native officers' and then 'Viceroy's Commissioned Officers' (VCOs). The top Indian officer rank in the cavalry was a rissaldar-major and in the infantry a subedar-major. In truth, though, the British administration proved reluctant to allow too many Indians to become officers. Although some candidates were sent for officer training in England to such prestigious institutions as the Royal Military College of Sandhurst, Indians would not have their own officer training academy in India itself until the arrival of the desperate necessities of the Second World War (1939-45). Sepoys continued to come from all population and religious groups in the subcontinent, such as Sikhs, Punjabis, Gurkhas, Jats, Dogras, Garhwalis, Muslims, Gujars, and Meors. The army companies were segregated into the groups just mentioned, but several different companies could be placed in the same battalion.

Not only essential to maintaining the British Raj in India, sepoys were also dispatched to protect colonial interests elsewhere such as Afghanistan, Persia, parts of the Indian Ocean, and Malaysia. Sepoys were still fighting for Britain in both the First World War (1914-18) and the Second World War when they served in Europe, East Africa, the Middle East, Malaysia, and India itself, both as privates and officers. Field marshal Bernard Montgomery (1887-1976), who had once been an instructor in the Indian Army, described the subcontinent's cadets as "splendid…natural soldiers and as good material as anyone could want" (Gilmour, 126).