The First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-42) was fought between the British East India Company (EIC) and, the Emirate of Afghanistan, the ultimate victor. The British were keen to control Afghanistan as they feared Russian expansion into South Asia, but the local tribesmen were fierce fighters. The war was extremely costly and included the disastrous retreat from Kabul in 1842.

Causes: The Great Game

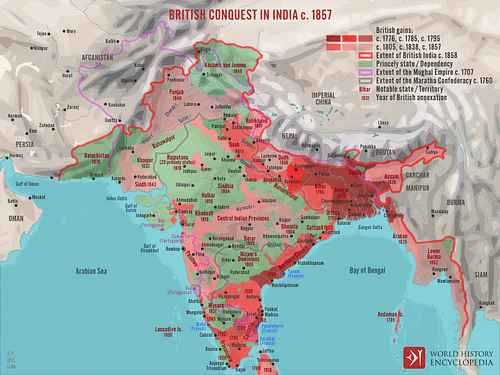

In the 19th century, Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), leader of the Sikh Empire, had greatly increased his territory in several military campaigns, which included defeating Afghan raiders and taking control of Lahore. Singh went on to take over Multan and Kashmir (1819), Ladakh (1833), and Peshawar (1834). The British East India Company, meanwhile, controlled much of the rest of India – either via direct rule or through a network of subsidiary alliances with Indian princely states. The EIC had also won a string of victories in conflicts like the four Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799), the three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1819), and the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814-1815). The EIC, effectively the colonial arm of the British government in Asia, next turned its attention to the very north of the Indian subcontinent and the frontier with Afghanistan.

In the wider world of empires, the British were concerned above all with the ambitions of their great rival Russia. The so-called Great Game (a phrase coined by Arthur Conolly but made famous by Rudyard Kipling in his novel Kim) was played between these two empires and it revolved around control of Central Asia. Persia and Afghanistan had acted as a buffer zone between these two empires, but each power sought to gain influence in that zone at the expense of their rival. This influence largely came from supporting one ruler or another against rival political factions, but another complication was the instability of relations between the Afghans and the Sikh Empire which resulted in a constantly changing frontier.

By 1838, the British feared that Russia intended to make a move on its Indian interests by involving itself or even taking over Afghanistan. In 1837, Persia, with Russian support, had besieged the city of Herat in northern Afghanistan. From there, Russia might move its influence eastwards and gain control of the crucial Khyber Pass, a mountain route on what became known as the North-West Frontier, which gave access to the plains of what is today Pakistan. Trade had long been conducted through this pass, but it could also be the road by which a Russian military invasion of India was launched. It was to forestall this possible Russian plan that the EIC decided to send a military force to the very north of the subcontinent, an inhospitable region that has embarrassed the military logistics of many powerful states from antiquity right up to the present day.

The Governor-General of the EIC in 1838 was Lord Aukland (1784-1849), and he decided on decisive action to strengthen Britain's position in the Great Game. Aukland sponsored a military expedition to enter Afghanistan and remove from the capital Kabul by force the Afghan ruler, Emir Dost Mohammad (1793-1863), who had shown alarming signs of ruling independently of British guidance. Dost Mohammad was also demanding control of Peshawar, then part of Ranjit Singh's Sikh Empire, an issue that could lead to an explosive war across the entire northern part of the subcontinent. The new puppet ruler was to be Shah Shuja (aka Shah Soojah and Shah Shujah Durrani), a former Afghan king (r. 1803-1809). Crucial military assistance was to be given by Ranjit Singh, with whom Shah Shuja had long been on good terms. The first move in the game came in June 1838 when the EIC signed a treaty with Ranjit Singh and Shah Shuja promising to protect existing borders. The EIC's military intentions were then boldly announced in the Simla Manifesto of October 1838, which included the following paragraph:

The welfare of our possessions in the East requires that we should have on our western frontier an ally who is interested in resisting aggression and establishing tranquility in the place of chiefs ranging themselves in subservience to a hostile power [Russian-influenced Persia], and seeking to promote schemes of conquest and aggrandizement…tranquility will be established upon the most important frontier of India, and that a lasting barrier will be raised against hostile intrigue and encroachment. His Majesty Schah Soojah-ool-Moolk will enter Afghanistan surrounded by his own troops, and will be supported against foreign interference and factious opposition by a British army…and when once he shall be secured in power, and the independence and integrity of Afghanistan established, the British army will be withdrawn.

(Barrow, 165-6)

Through November and December of 1838, two British army columns, one from Bombay (Mumbai) and the other from Bengal, headed for Afghanistan. As it turned out, the British badly overestimated local support for Shah Shuja. Not for the first time in their colonial exploits, the British had also convinced themselves that besides achieving a pro-British buffer zone between themselves and Russia's sphere of influence, they would also "be enabled to assist in restoring the union and prosperity of the Afghan people" (ibid). In both of these aims, the British were to be sorely disappointed.

Invasion

The British army that entered Afghanistan in March 1839 numbered around 21,000 soldiers and was led by Sir John Keane (1781-1844). This force did not face any unified opposition from the Afghan tribal leaders. The British benefitted from the Afghans having no centralised army except the private army of 4,500 men created by Dost Mohammad (1,500 infantry and 3,000 cavalry). In Afghan warfare, troops were raised as and when required through the carrot of prospective booty. There were to be no open battles in this war, but this was not to the advantage of the British.

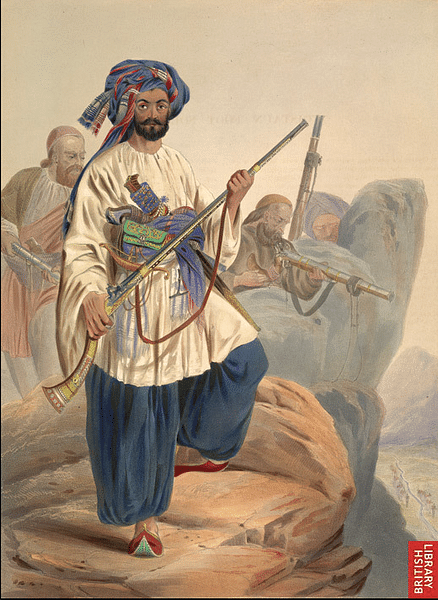

The British were armed with bayonetted muskets, swords, and artillery. The Afghans relied heavily on the long-barrelled and rather antiquated but highly accurate match- or flintlock musket known as the jezail. The jezail had a distinctive curved stock, which allowed more accurate fire from a horse. It was also an excellent weapon for snipers as the jezail had around twice the range of the standard British musket of the period. Afghan soldiers also had swords and knives, in particular, the super-sharp chora, which the British dubbed the "Khyber Knife".

The British force did face harassing attacks and sniper fire through the passes, but no great army came to meet it. Dost Mohammad, in any case, preferred to allow the British to stretch out their supply lines and let the terrain do the damage. Indeed, the greatest test was a logistical one given the great distance from the EIC army bases. Poor planning meant the British soldiers were soon put on half rations and the camp followers on quarter rations. Without roads, the supplies had to be transported by camel, but the land was so hostile that fodder had to be transported, too, ballooning the number of pack animals required. As so often in the region's history, entering Afghanistan and then keeping control there were two entirely different objectives.

Without significant military opposition in the field, the British felt confident enough to crown Shah Shuja the new emir on 25 April 1839 in Kandahar. In July 1839, the fortress of Ghazni – which guarded the route to Kabul – was taken after the British found out the Kabul Gate was not properly blocked. The wooden gate was blown up by a Bengal engineer Henry Durand using sacks of gunpowder, which was just as well since the British had neither heavy guns nor siege equipment to attack a fortress with a reputation for being impregnable. The fall of the fortress gave the British access to desperately needed food supplies.

The EIC army entered Kabul in August, and by September, the situation was already considered stable enough to send the Bombay army home. Dost Mohammad had fled Kabul when he had heard the news of the fall of Ghazni, but he did not give up his throne so easily; he led a force which defeated a small contingent of EIC cavalry at Purwandurrah on 2 November. The victory had no real value, though, as the former emir could not gather any united support from his countrymen, split as they always had been by family loyalties. Criticised ever since for being too cautious when a direct attack on Kabul may well have seen the British retreat in haste, Dost Mohammad gave himself up to the invaders later in November and was exiled to India shortly after.

Civil Unrest & War

The British now found themselves having to govern a people that did not want to be governed by foreigners. They tried to use bribes to exploit the age-old factions between the various Afghan tribes, which, though moderately successful at first, was a strategy that could not be sustained long-term as the British increasingly became the common enemy. Another weakness of the British occupation was the necessity to garrison forts in remote areas which then had little support from other British outposts.

The military coup and subsequent occupation, the unpopularity of Shah Shuja, Aukland's reforms in Afghanistan like the decision to reduce subsidies paid to local tribes, and anger at the fraternization between British soldiers and Afghan women, all combined to create the volatile conditions which led to a popular uprising and out-and-out war in 1841. The Afghan tribal leaders were still not at all united, but they at least had a common goal: kick the British out of Afghanistan.

Retreat From Kabul

Civil unrest in Kabul in November 1841 led to a mob killing Alexander Burnes, an important political officer of the East India Company. The unrest quickly spread as garrisons like the Gurkhas (EIC allies) at Charikar and the British at Ghazni were annihilated. There were some minor successes, such as the defence of the outpost of Tellalabad against the odds by a British force led by Sir Robert Sale, but the writing was on the wall for the British occupation. In Kabul, the lack of a decisive response to the unrest from the British only led to the situation worsening as more and more tribal leaders entered the fray. The EIC army was permanently camped outside the city, and its poor position for defence now became significant. The British troops came under fire from Afghan cannons and snipers hidden in the hills overlooking their camp.

Miscommunications, blunders, and the loss of supplies (which had all been incautiously stashed in one fort now taken over by the Afghans) meant the British lost control of the city. Low on supplies of ammunition and food, and with little prospect of any relief coming to their aid, the British army was forced to negotiate a withdrawal from Kabul in December. During this wrangling of terms, Sir William Macnaughten (1793-1841), the EIC envoy to Kabul was murdered by Akbar Khan (1816-1845), the son of Dost Mohammad. Clearly, the British position was a desperate one. To make matters even worse, the winter weather was bleak, and heavy snow was falling in Kabul and in the passes the EIC army would have to negotiate to reach the safety of India.

On 1 January 1842, the Afghan leaders agreed to permit a peaceful withdrawal of the British army and its attendants from Afghan territory. The British force was commanded by Major-General William Elphinstone (1782-1842), who came in for much criticism for not decisively quashing the rebellion when it had been in its early stages.

The British force of 4,500 soldiers (700 Europeans and 3,800 sepoys) and 12,000 camp followers left Kabul and headed for Jalalabad. To ensure the withdrawal was peaceful, four British officers were taken hostage. As it turned out, the more aggressive of the Afghan leaders got their way and consistently attacked the rear of the British column as it departed the country. In the chaotic withdrawal, camels and supplies were taken by raiders and 12 wives and 22 children of British officers were taken hostage. One of these, Lady Sale, survived her nine-month ordeal to write a bestselling diary of her captivity. The British had no tents and very few supplies as they crossed rivers and the inhospitable terrain. Hypothermia claimed many lives. By 10 January, there were only around 4,000 survivors from the original 16,500 that had departed Kabul.

On 11 January, the British column was attacked while going through the Jagdalak Pass. On 12 January, Elphinstone was taken hostage when he naively attended a conference with Akbar Khan to negotiate some sort of ceasefire; the general later died of dysentery. With only around 80 men left to fight, a last stand was made on 13 January on Gandamak Hill just outside the village of that name. Only one European survived the retreat from Kabul, Dr Brydon, who made it to Jalalabad on a lame pony. The retreat and destruction of an entire army was one of the worst military disasters in the history of the British Empire. Meanwhile, Shah Shuja was assassinated in April 1842. The British occupation of Afghanistan was at an end.

Retribution

The new Conservative government in Britain led by Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850) was determined to end the British meddling in Afghanistan, but not before a riposte was made for the Retreat from Kabul debacle. Kabul was recaptured by the experienced and meticulous Major-General George Pollock (1786-1872). Pollock had learnt valuable lessons on mountain warfare during the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814-16), and he became the first general in history to successfully lead an army through the Khyber Pass in April 1842. This army, known as the Army of Retribution, was essentially tasked with saving British face in the region. It was given the secondary objective of recovering any British prisoners still alive in Kabul. The army defeated Akbar Khan at Tezin and reached Kabul in September 1842 where the surviving British hostages were released – 10 women, 11 children, ad 85 soldiers. On 9 October, in a symbolic act of vengeance, the British torched and blew up the Great Bazaar in Kabul using barrels of gunpowder. The bazaar was selected for this treatment as it was here that William Macnaughten's body had been exposed to public insult. A round of revenge attacks, rapes, and plunder followed. Three days later, the British army marched out of Afghanistan and retraversed the Khyber Pass.

It was now clear that neither the British nor a puppet emir could rule without the consent of the local militant tribal leaders. Accordingly, Dost Mohammad was restored to power in 1843, and the Afghan tribes were permitted to live as they had always done, secure in their terrific mountains. As neither the Russians nor the British could control such a hostile region, the British settled for a policy of containment, one which became known as 'masterly inactivity'.

Aftermath

As the historian Surjit Mansigh here summarises, the EIC came to regret its folly in the mountains: "[the] war in Afghanistan cost the British in India fifteen million pounds sterling and 20,000 lives in four years of military disasters" (38). British imperial confidence was dented, as was the reputation of the armies of the East India Company, but in no way were colonial ambitions curtailed. The EIC now concentrated on defeating the Sikh Empire in the Punjab, that state having been beset with political turmoil since the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839. The EIC won both the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-6) and the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9) to take over yet another large slice of the Indian subcontinent. The British never gave up on the dream of controlling Afghanistan and so, despite a peace treaty signed with Dost Mohammad in 1857, there were two more conflicts to come, the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-80) and the Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919). The Great Game of empires continued into the 20th century, but the vital piece of Afghanistan remained fiercely independent and seemingly unconquerable.