"The Holy Roman Empire was in no way holy, nor Roman, nor an empire," wrote Voltaire, and this interpretation still dominates the popular imagination, so the Holy Roman Empire is treated as a bad joke, a pale parody of the glory of Rome. But was Voltaire right? Here we will explore the ideology that explains, and perhaps justifies, the name.

Renewal of the Roman Empire

The Franks were one of the many peoples who had migrated into Europe in the waning centuries of the Roman Empire. In the centuries following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, people carved out kingdoms, fought brutal wars, and rose to greatness—and fell from it—with bewildering speed. In the middle of the 8th century, Pepin the Short (r. 751-768), joined in the scrap when he usurped the throne of the Franks

Importantly, Pepin sought and got the blessing of the pope in order to get legitimacy for the new Carolingian Dynasty. As the bishop of Rome and the heart of the missionary movement, the pope had enormous prestige and influence over the other bishops to the north and west. He was the most prominent figure of the medieval church in western Europe, and with prominence came danger, so partnership with a great lord was very beneficial. However, the dynasty that Pepin founded is known by the name of his son, Charles the Great, Carolus Magnus, or as he is commonly known Charlemagne (l. 742-814).

Charlemagne extended what was already the greatest kingdom in western Europe until it encompassed (roughly) modern-day France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, western Germany, Switzerland, Slovenia, and northern Italy. On top of that, he was keen to spread Christian and classical teaching, in Latin, throughout this vast realm. After Charlemagne had defeated the pope’s enemies, the Lombards of Italy, the pope took their alliance one stage further. On Christmas Day 800 CE, Pope Leo III crowned him Emperor of the Romans. The story goes that Charlemagne was shocked and humbled by such an honour, but very likely this was a shrewd political move by both him and Leo to cement the prestige of the Church and the Crown.

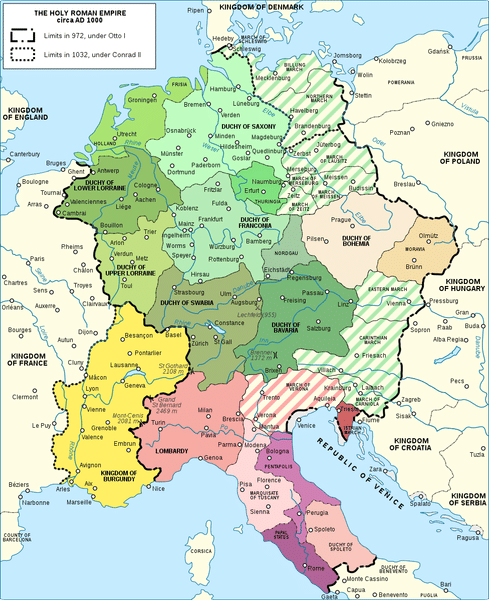

The lands of the Franks fractured on the death of Charlemagne’s son. The Treaty of Verdun, in 843, divided the Carolingian Empire among Charlemagne's grandsons. In theory, the northern Italian section continued to be the site of the imperial throne, but the eastern section—East Francia, covering much of what we now call Germany—was the most powerful. The Pope had long had problems with their northerly neighbours, and just as Leo had called in Charlemagne to conquer the Lombards in exchange for the imperial title, Otto the Great, ruler of East Francia, came and conquered northern Italy in 961. A year later, in 962, he was Holy Roman Emperor and a revitalised Holy Roman Empire came into being with its heartland in Germany.

Two Swords

Here the deal between pope and emperor became more than a bit of back-scratching. The partnership of a glorious lord and the leader of the church in the West underpinned a new civilisation, what today we call medieval Europe. Pope and emperor became known as the Two Swords, the symbolic leaders of Northern and Western Europe, or Latin Christendom. The pope would represent the shared religious life while the emperor would represent the political world they shared.

Emperor was not just some fancy title. It meant being the heir to mighty Rome, whose history sat heavily on the shoulders of Europe. To understand this, we need to look at the Old Testament Book of Daniel. Daniel prophesied that there would be four world empires before the Apocalypse. Translatio imperii was the name for how one world empire’s mantle was taken up by the next. In Late Antiquity, Christian interpretation of this prophecy was that each empire had shifted a little west, culminating in the Roman Empire. Given the world had not yet ended, as far as anyone could tell, this concept of translatio imperii could inspire and legitimise the renovation of a Christian Roman Empire, here in the post-imperial kingdoms of the far West. The revived Roman Empire was simply a continuation of the final earthly empire, and the people of Europe would see in the Apocalypse under its guidance.

The Byzantine Empire still claimed to be the Roman Empire, but the Latin West had an increasing sense of separation from the Greek East. Although the eastern and western churches were not yet formally divided in Charlemagne’s time, their cultures and associations had grown far apart. The western church, importantly, was dominated by the pope in Rome, while according to the East, he was only one bishop among many. The idea of a separate, western, Latin Christian-Roman civilisation made sense to the people who lived there. They tended to describe their state as the Renewal of the Roman Empire (Renovatio imperii Romanorum) rather than the Holy Roman Empire - that term took over in the 1100s - but the concept is the same.

Understood in this light, the light in which people at the time would have seen it, the combination of terms makes sense:

- Holy, the true Christians, the right-believers who uphold God’s truth in a world of heretics and heathens;

- Roman, the heirs of the Roman Empire and centred on the spiritual primacy of the city of Rome, whose bishop is representative of our shared religious life;

- Empire, led by an Emperor, the one ruler recognised by all the civilisation as the highest in rank and first in precedence, whose special authority represents common civilisation.

Interestingly the Eastern Roman Empire would later follow the same idea on different tracks. The Greek Orthodox and Latin Catholic Churches are considered to have officially split when the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople mutually excommunicated one another in 1054. The peoples who would become the East Slav had long been heavily influenced by the Greek Orthodox culture emanating from the Byzantines. After 1453: the fall of Constantinople to the Muslim Ottoman Empire, Moscow would claim the translatio imperii and call itself the ‘Third Rome’ with a caesar (Tsar) at the head.

Conflict between Pope & Emperor

This image of the Two Swords, pope and emperor as the ruler-representatives of Latin Christendom, was a rather dubious interpretation of a passage in Luke: "The disciples said, 'See, Lord, here are two swords.' 'That is enough,' he replied." (22:37-38). If it was built on shaky biblical foundations, the political ones soon cracked, too, and the Two Swords started to clash against each other.

First, reform movements in the 1100s energised the Church. They saw the Church as too lax, riddled with sin, and wanted to clamp down on priests getting married and monks living in luxury. The great Cluniac reforms sought to purify the daily life of medieval monks, and Pope Gregory VII wanted to impose good order and morality on all his priests, not just monks living in a medieval monastery. Now the church could not accept being a mere legitimising deputy to whoever happened to be in power, and because of its new, strict, hierarchical organisation, it had the power to fight for its influence.

Second, the Normans had entered Italy at the beginning of the 1000s. These warriors of fierce reputation had the power to fight for the pope and, as newcomers, craved the authority the church could give them. They did not always get along, but they always had the option of allying with the pope, who could now have a lordly protector other than the emperor.

The most famous example of a conflict featuring the pope against the emperor is the so-called Investiture Controversy. In 1076, Pope Gregory VII (r. 1073-1085) excommunicated Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1084-1105) after they disputed who could choose the bishop of Milan. It might seem like a very disproportionate action to a petty dispute, but the right to invest the bishops within the empire with the symbols of their office was deeply important to their authority. Unfortunately for Henry, his excommunication was the green light for a number of disaffected nobles to rise against him. He diffused the situation marvellously when he walked to Canossa, where Gregory was staying, and knelt barefoot in the snow until Gregory agreed to absolve him.

However, the question of investiture rumbled on, many more battles were fought, many more people died. The Concordat of Worms was a patch-up compromise in 1122, but the underlying tension between these two pre-eminent figures remained. Neither could quite fully assert their authority over the other, and conflict flared up again and again. Pope John XXII and Emperor Louis IV’s struggle in the 14th century is memorably depicted in Umberto Eco’s bestselling novel The Name of the Rose.

So the Two Swords stayed at each other's throats. It never worked seamlessly or, frankly, even particularly well. However, conflict should not be interpreted as failure. There was so much controversy precisely because the issue mattered to those involved. The Pope and the Emperor were like two boxers fighting in an arena they had built for a trophy they had invented. They were bickering over their place and relative power within the framework they had set up. It was very hard—and not at all in their interests—to think outside of that framework. The fact that they fought so hard is indicative of how important it was to them to claim the symbolic leadership of the new civilisation they had founded.

Sovereignty: Both Swords Broken

Over the course of the Middle Ages, the Holy Roman Empire began to lose its pre-eminence among the powers of Europe. The Two Swords concept gradually faded in relevance. For sure, there were mighty emperors like Frederick I Barbarossa (r. 1155-1190) and his grandson Frederick II (r. 1220-1250), who conquered Sicily and even briefly liberated Jerusalem in the Sixth Crusade. Occasionally they received direct homage from other kings, as when Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1191-1197) captured Richard I of England, (aka Richard the Lionheart, r. 1189-1199) in 1193. Of course, Richard did this under duress, but the fact it was possible is important. King Richard could not have legally given submission to any other monarch in Europe because no other monarch in Europe had a title that outranked. However, the claim to universal dominion was limited to occasions like this.

Beyond the lands they held with their kingly titles, like Germany and northern Italy, the emperors had little authority. They held court and raised their armies more in their capacities as Kings of Germany rather than Holy Roman Emperors. Philosophers began to argue for the sovereignty of monarchs and cities. That means that each king, queen, and city-state was free to rule as they wished within their realm over temporal matters, without reference to the emperor. In spiritual matters, they still had to respect the church, of course. Some scholars argued that this was a right as a member of the universal empire, some that the Roman Empire had never been restored at all, and others that it sprang from the special laws and customs of each people. Whatever the details, the effect was the same: the rejection of imperial authority by Europe outside the empire.

The emperor’s vassals in Germany continued to assert their independence. In 1078, during the Investiture Controversy, the strongest of these vassals had responded to Gregory’s excommunication of Henry IV by electing a new king. Their ‘anti-king’ died within two years, and Henry had regained the initiative by then, but the legacy of that action was that the most prominent German princes reserved the right to decide who the next king of Germany would be. Candidates now had to placate and bribe these electors and so they stayed very commanding and autonomous. They even broke the link between the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor when they declared, in 1356, that the imperial title would be assumed automatically by whoever they elected as King of Germany. This made successions smoother, and the electors more influential, but damaged the idea that the empire might represent the Latin Christian world.

Europe’s shared civilisation was changing. Voltaire called it "a sort of great Republic divided into several states" of which the empire was only one. It had, at best, ceremonial precedence, a first among equals kind of title. Even when Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556) united the Holy Roman Empire with Spain and its vast overseas colonies and it looked as if a universal empire was once again possible, the states of Europe jealously guarded their sovereignty. Henry VIII of England’s (r. 1509-1547) 1533 Act in Restraint of Appeals, part of his break with the Catholic Church, begins by stating that "this Realm of England is an Empire". The point of this flourish was to assert that England would respect no law but its own. It was explicitly rejecting the idea that anyone was above the king. Of course, this was directed at the pope. The medieval concept of sovereignty had rejected the emperor, now Henry VIII was taking the logical next step and rejecting the pope, too. In the duel of the Two Swords, both lost.

Civil War

However, the Holy Roman Empire was not just another European state. Outsiders may not have paid its imperial trappings much mind by the Early Modern Period (from about 1500 onwards), but its peculiar, imperial history gave it special features and special meaning to the people who lived in its boundaries.

Charlemagne changed Europe forever when he was crowned in Rome on Christmas Day 800, so too did a German monk named Martin Luther when he fixed his 95 theses to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral on Halloween 1517. Luther set in motion a chain of events that we now called the Protestant Reformation. This was the context to England’s break with Rome, and that was only one of many revolutionary events sparked by reformers like Luther.

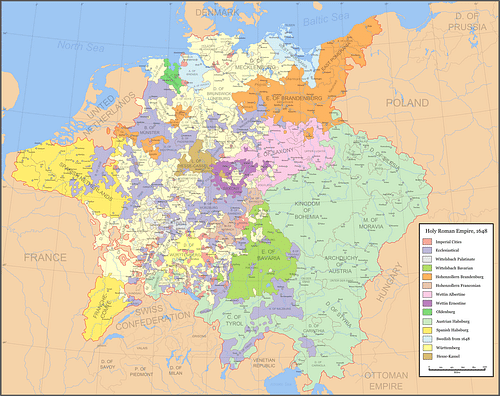

Religion tore apart the empire for a hundred years. The very word Protestant comes from those Lutheran princes who protested a Catholic decision in the Reichstag (the meeting of all the rulers in the empire) of 1529. Those Protestants formed the Schmalkaldic League and negotiated the Peace of Augsburg (1555) in which, despite their defeat in war, they got official privileges to practice their religion. As the Spanish Netherlands and France descended into civil war, Catholic and Lutheran princes alike rallied around the empire as a neutral framework in which they could practice their religions. The settlement broke down as certain influential princes converted to Calvinism, another form of Protestantism not accepted by the Peace of Augsburg, and the different denominations bickered over whose candidates would control the lucrative prince-archbishoprics. These tensions exploded while the emperor was distracted fighting the Ottomans. Many historians consider the subsequent Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) as the real breakup of the Holy Roman Empire, a time when the whole edifice descended into horrifying butchery and, afterwards, was nothing but a hollow shell. Indeed, Voltaire wrote his famous quotation in the period after the Thirty Years’ War.

For the people of the Holy Roman Empire, though, all of these were civil wars into which external powers (controversially) intervened. People were fighting inside their empire over disagreements about what it should become. Unlike Anglican England, Lutheran Sweden, or Catholic France, the empire accepted several Christianities and could do this because it was not the property of a single dynasty or dominated by a single group. It remained a non-ethnic, non-religious, overarching identity that could embrace many particular and local identities. Where people stood inside that framework was perpetually the source of conflict, on and off the battlefield, but the framework itself survived. The final death of the empire in the first years of the 19th century was the omen of new, very different ideas about empires.