The Counter-Reformation (also known as the Catholic Reformation, 1545 to c. 1700) was the Catholic Church's response to the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648). It is usually dated from the Council of Trent in 1545 to the end of the Great Turkish War in 1699, but according to some scholars, it continued afterwards and is ongoing in the present day.

Although efforts to reform perceived abuses and errors in the Church predated the Protestant Reformation, they were never as effective as those of the Counter-Reformation. The medieval Church was quick to crush challenges to its authority, although some members working within the Church would periodically encourage reform without suffering persecution. These efforts never made a significant difference in steering the Church back from its involvement in worldly pursuits to spiritual matters.

When Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) began the Reformation in 1517, the Church tried to silence him as it had earlier reformers, but due to widespread support generated largely by the printing press, it was unable to. By 1530, Luther's right-hand man, Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560), had written the Augsburg Confession, which was countered in that same year by the Catholic confession known as the Confutatio Augustana, and according to some scholars, this is when the Counter-Reformation began. The Confutatio Augustana clarified the Church's position on various topics and denounced the Protestant Reformation as heresy.

When it became clear that the new movement would not simply evaporate, Pope Paul II (served 1534-1549) convened the Council of Trent (1545-1563) to affirm the truths of the Church and reform abuses and errors. Throughout the period of the Council of Trent, and afterwards, Catholic authorities amended the sales of indulgences, improved the education of the clergy, established new rules for monastic orders, introduced profoundly significant doctrines regarding the use of art, music, and architecture in worship, and worked toward returning the Church to its prior centrality in people's lives. Primarily, it sought to elevate itself – and thereby its adherents – above the teachings and practices of the Protestant sects.

The main focus of the Counter-Reformation, however, was the establishment (or reestablishment) of the concept of ultimate, objective truth. The earliest Catholic argument against the activism of Martin Luther was that if anyone who could read the Bible could claim they knew the truth, then there was no 'truth,' only opinion, only interpretation. Without a strong, central, spiritual authority to determine truth from untruth, each person or group of like-minded people could claim 'truth' for themselves exclusively. This argument proved prophetic as this is precisely what did happen during and after the Protestant Reformation and continues to in the present. Scholars who claim the Counter-Reformation is ongoing today cite the Church's present stand on various social and cultural issues as evidence of the Counter-Reformation's claim that the Catholic Church is the sole arbiter of spiritual truth.

Medieval Church & Reform

The medieval Church was understood as the only valid spiritual authority for Christians, claiming a direct commission from Jesus Christ to Saint Peter (regarded as the first pope) as given in Matthew 16:18-19. In order to carry out its divine mission, a hierarchy had been instituted with the pope as head of the Church, followed by cardinals (advisors and administrators), bishops and archbishops (presiding over specific regions or cathedrals), priests (in charge of villages and parishes), and monastic orders. Although this hierarchy was originally intended to facilitate the Church's mission of saving souls, it had been corrupted by involvement in politics and the acquisition of power.

By the 8th century, Church documents like The Donation of Constantine claimed the Church's authority superseded a monarch's, and, by the early 14th century, the Unam Sanctam had been issued, making clear that there was no salvation outside of the Church and everyone – believers and unbelievers – should be subject to the pope, God's representative on earth. The pope issued his decrees in Latin, which traveled down the hierarchy and were transmitted to the people, but the majority of the European population felt no personal connection with these, nor with the Bible, prayers, or services, because they did not understand Latin. The disconnect between the Church hierarchy and congregations was worsened by poorly educated priests, bishops, and cardinals, even popes, who were more interested in their own comfort than in advancing the Christian message.

Movements advocating reform began in the 7th century when the Paulicians encouraged a return to the simplicity of the gospel message and early Christianity, as depicted in the Book of Acts. The Paulicians were persecuted by the Church and eventually wiped out by the 9th century. Others followed, also condemned as heretics, including John Wycliffe (l. 1330-1384) and Jan Hus (l. c. 1369-1415). There were others, however, who worked within the Church hierarchy for reform, such as the scholar and priest Lorenzo Valla (l. c. 1407-1457), who proved The Donation of Constantine was a forgery and had no scriptural authority, or Desiderius Erasmus (l. 1466-1536), the great humanist theologian, scholar, and priest.

Luther & Zwingli

The efforts of men like Valla and Erasmus to redirect the Church back to its mission failed to address the divide between ecclesiastical authority and the people and, further, did not prevent abuses of power by clergy or official policies that put a price on salvation. Among these was the sale of indulgences – writs promising to lessen the time spent in purgatory after death – which generated significant wealth for the Church. It was the sale of indulgences that prompted Martin Luther's 95 Theses in 1517, which set the Protestant Reformation in motion in Germany, while, in Switzerland, Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) initiated his own reforms in response to similar abuses.

By 1522, the activism of Luther and Zwingli had already inspired similar movements in Italy, France, the Netherlands, and Spain. The Church had attempted to silence Luther and, when this failed, engaged in debates and published pamphlets to discredit reformers and maintain its authority. Although most Europeans were illiterate at this time, publications on this new religious controversy were bestsellers that were given public readings, which drew wider support for the Reformation because it connected the people directly with their faith and, at first, seemed to promise a new order in which all social classes would be equal or, at least, the lowest class would not have to bear the financial burden of the others.

Augsburg, Loyola, & Trent

The Reformation's message appealed to anyone who felt disenfranchised by the Church and social hierarchy, as evidenced by the Knights' Revolt (1522-1523), which sought to establish the 'new teachings' in Germany, and the German Peasants' War (1524-1525), an attempt to overturn the status quo. By 1530, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, understood he needed to resolve these issues and convened the Diet of Augsburg at which the Protestants of Germany presented their Augsburg Confession (written primarily by Luther's right-hand man Philip Melanchthon, l. 1497-1560) and the Catholics countered with their Confutatio Augustana (mainly written by Luther's antagonist Johann Eck, l. 1486-1543). Both sides rejected the confessions of faith of the other, and the confessions became rallying points for the opposing views.

In 1521, the Basque soldier Ignatius of Loyola (l. 1491-1556) was wounded at the Battle of Pamplona, and during his convalescence, he received visions he understood as calling him to the service of the Church. He renounced his former life, took up the study of theology, and with six others in 1534, vowed to defend the Catholic Church against heresy, spread its message of universal salvation, and help it in reforming its weaknesses. In 1539, Loyola received approval from Pope Paul III for the establishment of the Society of Jesus (better known as the Jesuits), which he formed in accordance with military hierarchy and discipline.

The Jesuits focused on countering the claims of the Reformation and maintaining the absolute authority of the Catholic Church. In his Spiritual Exercises (1548), Loyola made his stand clear, writing:

If we wish to proceed in all things, we must hold fast to the following principle: What seems to me white, I will believe black if the hierarchical church so defines. For I must be convinced that in Christ our Lord, the bridegroom, and in his spouse the church, only one Spirit holds sway, which governs and rules for the salvation of souls. For it is by the same Spirit and Lord who gave the Ten Commandments that our holy mother church is ruled and governed. (Point 13, Janz, 429)

In maintaining the singular authority of the Church to define truth, Loyola supported the argument first advanced by Johann Eck against Luther and Andreas Karlstadt (l. 1486-1541) at the debate in Leipzig in 1519: if there was no central spiritual authority to define 'truth,' then anyone's interpretation of 'truth' could be considered valid, in which case there was no truth, only opinion. Eck had claimed that only the Church could interpret scripture because the Bible was not just any book and its teachings were more complex than they appeared. One required educated theologians to interpret the work and preach its message to the laity.

Luther had rejected this claim as another attempt by the Church to maintain power and insisted that one only needed individual faith and the scripture to be justified before God. Loyola not only rejected Luther's claim but took measures against it by establishing universities and seminaries in which priests would be educated in scriptural interpretation and ministry in accordance with the Church's teaching that one was only justified by adherence to Catholic precepts. The Council of Trent also rejected Luther's claim, supporting Eck's, in a number of its final provisions, notably Canon 14:

If anyone says that man is absolved from his sins and justified because he firmly believes that he is absolved and justified, or that no one is truly justified except him who believes himself justified, and that by this faith alone absolution and justification are effected, let him be anathema. (Janz, 413)

Anathema meant to be condemned or cursed and, in this case, excommunicated. The Council of Trent was convened to reaffirm Catholic doctrine, amend errors and abuses, and condemn the teachings of the Protestant sects. Protestant delegates were invited to discuss and debate points, but it was made clear they would have no voice in voting on the decrees. The council rejected Luther's claim that one was justified by faith alone and maintained that the Church was the sole authority in both the interpretation of scripture and its teachings. The selling of indulgences was amended (though not abolished) as were traditions such as the veneration of the saints and relics, the understanding of the Eucharist, the use of Latin in celebrating the Mass, and the benefits of iconography and music in worship.

Truth & Untruth

The reforms of The Council of Trent, while sincere, were also aimed at undermining the Protestant criticism of the Church and marking a distinct difference between Protestant and Catholic visions of Christianity. The rejection of Luther's 'faith alone' and 'scripture alone' claims was central in establishing the Catholic claim as the sole authority in determining spiritual truth. By 1545, there were many different Protestant sects, each claiming they held to 'true Christianity' while the Church countered that, if all of these claimed to be right, none of them could be right, while the Church – which had the original mandate from Jesus Christ himself – could not possibly be wrong.

The Jesuits and other Catholic clergy did not just make this claim and leave it as though it were self-evident, but they sought to refute the Protestant claims of 'faith alone' and 'scripture alone' through recourse to classical literature and, specifically, the discipline of philosophic skepticism as formulated by Sextus Empiricus (l. c. 160 to c. 210 CE) and based on the views of the skeptic philosopher Pyrrho of Elis (l. c. 360 to c. 270 BCE). Pyrrho maintained that one's senses could not be relied upon in making judgments or coming to conclusions and so the best course was to refrain from doing either or taking other people's conclusions too seriously.

The Church drew directly on the work of Empiricus, who wrote extensively on the subject, to argue that the claims made by the Protestant leaders were in error because they were nothing more than opinion. Empiricus writes, "To every argument an equal argument is opposed" (Outlines, XXVII.202), in clarifying Pyrrho's claim that all argument is simply opinion, cannot objectively be defined as related to 'truth' and, therefore, is nothing to engage in or become upset by. The Church proceeded, so to speak, from this point to the question, "What if there were someone or something that could resolve an argument objectively, so it was no longer a matter of opinion but truth?"

They then answered that question with the line from scripture: "Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and lean not on your own understanding" (Proverbs 3:5). The Church, they claimed, as God's representative on earth, could be trusted to tell the truth about the nature of the divine, while the Protestants were leaning on their own understanding and had rejected truth for untruth. This argument is the basis for Loyola's claim that one should accept white is black if the Church says white is black and was also the underlying justification for other decrees by The Council of Trent, such as The Inquisition and the Index of Prohibited Books. The Church had allowed its authority to be challenged in 1517 and was not about to make that mistake again. The Jesuits, especially, vowed to uphold that authority and defend the Church with their lives.

Architecture, Art, & Music

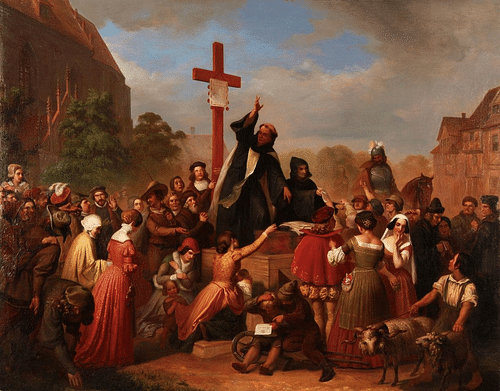

The Jesuits became famous for their skills in debate and refutation of Protestant claims and were among the best-educated and most articulate defenders of Catholicism. While these 'soldiers of Christ' were at work as missionaries and apologists, the Church furthered its aim of reestablishing its centrality and authority through grand architectural projects and commissioning compositions and artworks to elevate the souls of believers and exemplify the grandeur of the Catholic vision.

This style – whether in art, architecture, dance, or music – came to be known as baroque, meaning "irregularly shaped" to differentiate it from the classical style. Baroque churches and cathedrals featured wide, open spaces, illuminated windows, and elaborately painted domes, with the altar as the focal but inviting a congregant into a sacred space, which encouraged one to look up and around at the various works of art, including the building itself. The immensity of a Catholic house of worship was purposefully designed to impress upon one the greatness of God and the individual's place in His world, to serve as an embodiment of the scriptural admonitions "The earth is the Lord's, and the fullness thereof" (Psalm 24:1) and "God is in heaven and you are on the earth; therefore let your words be few" (Ecclesiastes 5:2). The artwork commissioned for these structures was intended to serve the same purpose.

Although not all baroque art dealt with religious themes, many of the most famous did, such as The Calling of St. Matthew by Caravaggio or The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa by Bernini. Music followed the same paradigm as composers created works celebrating Christian themes whose aim was an elevation of an audience as in the cases of two of the best-known works, George Frideric Handel's Messiah and Johann Sebastian Bach's St. Matthew's Passion. Although the Lutherans had allowed music as part of worship and, eventually, art, it was more modest. The Calvinists (followers of John Calvin, l. 1509-1564) banned music, dance, and any kind of iconography as idolatrous. The Catholic Church sought to distance itself from these sects by encouraging an appreciation of art and music, which was intended to encourage one's faith and close the previous divide between clergy and laypeople in the Church through direct communion with God.

Conclusion

The Church responded to the criticism that the hierarchy ignored individual interpretations of Christianity by recognizing figures such as Saint Theresa of Avila (l. 1515-1582) and Saint John of the Cross (l. 1542-1591) while also noting their earlier recognition of other mystics including Hildegard of Bingen (l. 1098-1179) and Julian of Norwich (l. 1342-1416). These individuals, it was noted, claimed personal revelations just as Luther and other Protestants did but these were in line with the accepted teachings of the Catholic Church and so could be regarded as true. The claims of the reformers were dismissed as individual interpretation, which amounted to opinion, not truth.

The Counter-Reformation continued pursuing its goals throughout the 17th century, sending Jesuit missionaries around the world to further establish the authority of the Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church until it concluded with the dissolution of the Holy League in 1699. The Holy League was an alliance of Christian nations mobilized against the aggression of the Ottoman Empire, and once that threat was neutralized after The Great Turkish War, the league disbanded.

This event is considered by some scholars as the end of the Counter-Reformation in that it concluded a century of conflict encouraged by, or directly attributed to, differences in religion. According to some views, however, the Counter-Reformation has never ended as, by definition, it was a response to the challenge of widespread heresy and continues to stand against what it considers heretical views today. In this view, the Counter-Reformation is ongoing as the Church continues its claim as the first and, therefore, truest embodiment of the Christian vision.