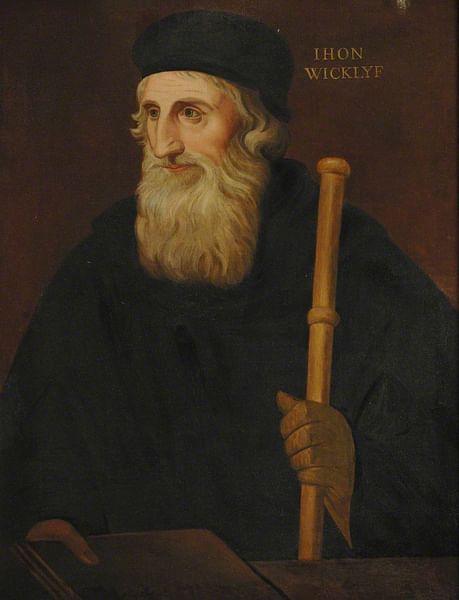

John Wycliffe (l. 1330-1384, also John Wyclif) was an English theologian, priest, and scholar, recognized as a forerunner to the Protestant Reformation in Europe. Wycliffe condemned the practices of the medieval Church, citing many of the same abuses that would later be addressed by other reformers. He is best known for translating the Bible into Middle English.

Wycliffe grew up in a period when the Holy Roman Catholic Church was the supreme power in Europe. The Church had already split into the Western Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church in the Great Schism of 1054, but this did nothing to diminish the power of the Church in Europe, which increasingly involved itself more in secular political matters than religious issues. Anyone objecting to the Church's policies was silenced, and there was no other religious authority one could turn to for appeal.

Wycliffe was an Oxford-educated theologian who objected to the Church's abuses, challenged the hierarchy, and claimed the Christian scriptures were the supreme authority, not the pope. He developed the theology of two domains, an earthly Church and idealized Church, clearly based on Platonic principles he had learned from his close reading of the works of Saint Augustine of Hippo, and claimed the earthly Church had strayed far from what it should have been.

He was protected from persecution by powerful political allies in England and by the distractions caused by the Western Schism (1378-1417) during which there were two popes, one at Rome and another at Avignon, France, with different factions of clergy supporting one or the other. His ideas were spread by his followers, known as Lollards, who also assisted him in translating the Bible from Latin into Middle English. Although he came into conflict with Church authorities in England between 1377-1382 and was deprived of his teaching position at Oxford, he was not excommunicated nor officially branded a heretic.

After his death, however, he was decreed both in 1415. His remains were dug up in 1428, burned, and thrown into the River Swift. He is recognized as a proto-reformer as many of his claims and objections were voiced first by Jan Hus (l. c. 1369-1415) and then by later reformers such as Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546), who took them further, sparking the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648) that broke the power of the Church.

Medieval Church in England

To understand the kind of courage it took to challenge the Church in the Middle Ages (c. 476-1500), one must recognize the authority it claimed and the kind of power it commanded. The Church was the only means by which one could attain eternal salvation, and as heaven, purgatory, and hell were recognized as certainties awaiting one after death, the precepts of the Church had to be followed without question if one wished to avoid the suffering of the latter and be rewarded in the former.

The Church claimed this authority directly through scripture citing Matthew 16:18-19, where Jesus appoints the apostle Peter as "the rock upon which my church will be built", which church authorities claimed made Peter the first pope and each pope to follow his successors. As the Church gained more power, however, it became more involved in extending its reach and expanding upon that power than concerning itself with spiritual salvation and the Christian walk. By the time of Wycliffe, the Church held approximately one-third of the land in England, tax-free, and through the practice of simony, officials were able to place friends and relatives, often unqualified, in comfortable and lucrative ecclesiastical positions.

Early Life & Education

The exact year of Wycliffe's birth is disputed, with some scholars placing it as early as 1320, but it is generally accepted he was born in the village of Hipswell, Yorkshire, England in 1330. His family may have been sheep farmers and seem to have been related to the wealthy Wycliffe family of Wycliffe-on-Tees, located a few miles from Hipswell, though this claim has been challenged as well as the suggestion Wycliffe was born in that village. Nothing is known of his youth except that he probably began his education at home, or nearby, at an early age.

He was already a student at Oxford in 1345 and survived the Black Death pandemic of 1347-1352. The suffering caused by the plague and the inability of the Church to address this deeply influenced the young theologian, who developed a generally pessimistic view of the human condition and, in time, a marked skepticism regarding the power of the Church to do anything to improve people's lives. Scholar Christopher Ocker notes:

[The Church maintained] that evil is an inherited trait (original sin) and that being good requires divine aid (a gift of grace). Implicit here is an inverse proportion of human moral disability to divine agency. The more disabled, the more constant and unilateral was God's intervention with grace. (Rublack, 25)

The only "divine aid" available was through the Church, but as Wycliffe would have observed, none of the Church's aid during the plague had any effect on alleviating the suffering of the people while many, if not most, of the clergy concentrated their efforts on protecting themselves and amassing more wealth and greater comfort. Wycliffe's mentor, Thomas Bradwardine (l. c. 1300-1349), scholar and archbishop of Canterbury, died of the plague, and his death, contrasted with the survival of so many clerics Wycliffe thought inferior, inspired in him greater piety and determination to live as closely as he could to the precepts of scripture rather than the ordinances of the Church.

Even though Wycliffe did not challenge the Church's teachings at this time, he did argue with highly respected theologians, notably William of Ockham (l. c. 1287-1347), over the meaning and significance of the Lord's Supper as celebrated at Mass. The insistence of the Church on human sinfulness and its claim as the only avenue for divine grace seemed to Wycliffe at odds with its preoccupation with rituals that, as far as he could see, were not supported by scripture in the way they were being observed.

Politics & Controversy

Still, he continued to adhere to the orthodoxy of the Church, receiving his bachelor's degree in 1369 and his doctorate in theology in 1372. As early as c. 1361 he was appointed Master of Balliol College at Oxford and represented the university in a dispute with the pope over local mendicant orders recruiting students, usually against the wishes of their families and sometimes, it seems, those of the students themselves. The pope ruled against Wycliffe and Oxford in this dispute, but it marked his first challenge to papal authority, and it may have been this event that caught the attention of the powerful noble John of Gaunt (l. 1340-1399), one of the sons of King Edward III (r. 1327-1377), who would become one of Wycliffe's most important allies.

It is more likely, however, that Wycliffe caught Gaunt's attention in 1374 when he was sent as part of a delegation to Pope Gregory XI (served 1370-1378) to settle disputes over the king's rights vs. the pope's in land ownership. Wycliffe had appealed to the pope for help in a private matter concerning an appointment at Oxford that had been denied but still took the king's side in this dispute, losing him his appointment but gaining him the favor of the royal house. This same year he received his appointment to the parish of St. Mary's Church in Lutterworth, which he would retain the rest of his life, indicating he was still in good standing with the Church at this time.

By 1377, however, he was censured by Pope Gregory XI for his work On Civil Dominion, which developed the theological arguments he had presented in 1374. Further, Wycliffe had begun using his position as pastor at Lutterworth to criticize the pope and the church hierarchy as corrupt and land-greedy. His central argument in On Civil Dominion was that the Church had no business acquiring enormous tracts of land and should relinquish these to civil authorities, return to the simplicity of Jesus and his apostles and, like them, live in a state of poverty to better minister to the people.

Conflict with the Church

Wycliffe was called to London to appear before William Courtenay (l. c. 1342-1396), archbishop of Canterbury, to explain himself and answer for the seeming errors he had fallen into. Courtenay seems to have regarded Wycliffe as a heretic or, at least, tending toward subversion, and thought to have made quick work of the problem. Wycliffe had been placed under house arrest when he was censured, and Courtenay appears to have thought he would be easily condemned by his own words at the examination in February 1377.

Wycliffe, however, appeared in London accompanied by John of Gaunt and another powerful noble, Lord Henry Percy (l. 1341-1408), Earl of Northumberland, as well as a number of clerics who supported him. The simple examination and condemnation Courtenay may have expected was upended by Gaunt and Percy challenging his authority and defending Wycliffe. By this time, Wycliffe's stand against church authority was well known, and so a large crowd of the peasantry had also arrived to support him as a challenge to the Church was understood by them as a blow against the established order that kept them in poverty.

Courtenay could not condemn Wycliffe without risking a riot and possibly incurring the wrath of the nobility but could not dismiss the charges (which are unknown since the examination never took place) without compromising the authority of the Church. He was left with no option but to warn Wycliffe against preaching unorthodox doctrines and then letting him go.

Wycliffe was popular with the nobility because they saw in his works a legitimate challenge to the authority of the Church as he was himself a doctor of the Church and was arguing from scripture. The Church's loss of power and land could only mean a gain for the nobility of England. The peasantry also supported Wycliffe, generally speaking, for more or less the same reason as they hoped that any upset of the status quo would alleviate the poverty they lived in. The power of Wycliffe's arguments came from his understanding of scripture, the writings of the Church Fathers (primarily St. Augustine), and his skill as a writer, orator, and preacher, as well as his vision of what the Church should be as contrasted with what it had become. Scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch comments:

Wycliffe was a philosopher in a tradition which saw invisible, eternal realities as more representative of reality than the experiences of the everyday world. He drew on the assumption to make a damning contrast between the material, powerful, and wealthy Church over which the bishops and the Pope presided, and the eternally existing Church beyond materiality: this latter true Church was a mystical source of grace which the Bible revealed not simply to clergy but to all God's chosen faithful. (35)

Accordingly, one did not need the Church to receive God's grace, one only needed scripture, which revealed the personality of God, and prayer, which placed one in direct communion with the divine.

Translation of the Bible

The Bible at this time was only available in Latin, which few people outside the educated clergy could read. The work had been translated from Hebrew and Greek to Latin by Saint Jerome (l. 347-420) with the help and encouragement of his associate Saint Paula (l. 347-404), and their version (known as the Vulgate) was mandated by the Church as completely authoritative and infallible. Any suggestion that the Bible should be translated into the vernacular of the time, such as English, was regarded as heresy and anyone who attempted it as a dangerous threat to the Church.

Wycliffe, however, noted that St. Jerome had himself translated the work from the original languages to the vernacular of his day, Latin, as the term "vulgate" made clear, and so commenced his own translation from Latin to English in the early 1380s, with the first version appearing in 1382. The work was printed using xylography (woodblock printing), the same process by which he had disseminated his earlier works (as the printing press had not yet been invented), and became a bestseller. Although most people could not read English, they could understand it when read to them, and the Bible in the vernacular was a direct challenge to church authority, which no longer controlled how the scriptures were to be understood.

The Church was incensed, and worsening Wycliffe's position, many of his allies among the nobility (notably Gaunt) deserted him when he challenged the validity of transubstantiation (the transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ during Mass) claiming it was unbiblical and noting it was a fairly recent concept invented by the Church. The archbishop of Arundel summarized the feelings of the Church toward Wycliffe when he condemned him as a heretic after his death, writing:

This pestilential and most wretched John Wycliffe of damnable memory, a child of the old devil, and himself a child or pupil of Anti-Christ, crowned his wickedness by translating the scripture into the mother tongue. (Stewart, 15)

Wycliffe was also blamed, rightly or wrongly, for the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, which, although he condemned, he is thought to have contributed to by challenging the accepted social order. However the church hierarchy felt about Wycliffe, the people responded eagerly to the English translation, which went through multiple printings and has survived to the present in over 200 copies, attesting to its popularity in its time. Contrary to some claims, however, his is not considered the first English translation of the Bible as it only worked from the Latin; the first English translation is the Tyndale Bible in 1535 by William Tyndale (l. c. 1494-1536), who worked from the original Hebrew and Greek.

Conclusion

Although Wycliffe was censured by the Church, he was never excommunicated nor branded a heretic in his lifetime. His followers came to be known as Lollards, a pejorative term coined by their opponents whose meaning is unknown but thought to refer to a "lolling" of the tongue as they were thought to be speaking nonsense. These adherents are thought to have been vital in the work of translating, printing, and disseminating the English version of the Bible, which was adopted as orthodox by many lay preachers and parish priests who continued to use it even after Wycliffe was posthumously condemned.

In 1382, Wycliffe was again summoned to answer for his "errors" and again left the synod in good standing with the Church and continued preaching the same condemnations of clerical abuses as before. He is thought to have repeatedly avoided the fate of others condemned as heretics due to the continued support of nobility, even though many had distanced themselves from him. He died of a stroke in late December 1384 and was buried in consecrated ground.

At the Council of Constance in 1415, however, after his works had inspired the reform movement of Jan Hus, Wycliffe was condemned as a heretic, his remains were exhumed and burned, and scattered into the River Swift. His supporters would later note that the Church's actions in this only highlighted Wycliffe's profound influence, as just as his ashes were dispersed into the river that ran to the sea that hugged distant shores, so had Wycliffe's words, and the example of his life touched people around the world