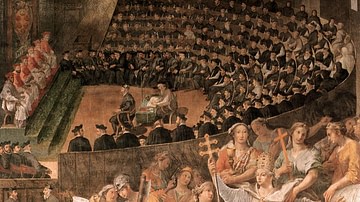

The Council of Trent (1545-1563) was a meeting of Catholic clerics convened by Pope Paul III (served 1534-1549) in response to the Protestant Reformation. In three separate sessions, the council reaffirmed the authority of the Catholic Church, codified scripture, reformed abuses, and condemned Protestant theology, establishing the vision and goals of the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

The Counter-Reformation (also known as the Catholic Reformation, 1545 to c. 1700), which was launched to affirm the Church's vision of Christianity and reform abuses, is understood to begin with the Council of Trent, convened to address these matters. Initially, the meeting was supposed to be ecumenical, involving both Protestant and Catholic clergy, and set for 1537, but war and various disagreements postponed the council until 1545, by which time the Catholic clergy had voted to deny Protestants the right to vote on any decisions or decrees. Although Protestants were invited, none participated. Many Catholic clergy from France and Germany also refused to attend for various reasons, including the difficulty of travel to the site in Northern Italy.

Although the Council of Trent has sometimes been characterized as one overly long meeting, it only met for three sessions (consisting of a total of 25 actual meetings) between 1545-1563:

- First Session: 1545-1549

- Second Session: 1551-1552

- Third Session: 1562-1563

The first and second sessions were prorogued (discontinued without dissolving a body of delegates), and so the council's dates are given as 1545-1563 because that is how long it was officially in session. The delegates did not meet regularly for 18 years, however, and many who attended the first differed from those at the last. The outcome was a series of decrees reforming abuses within the Church, condemning the Protestant Reformation and Protestant theology, affirming the truths of the Catholic Church and its spiritual authority, and codifying scripture.

Background & Necessity

The Protestant Reformation began in the Germanic territories of the Holy Roman Empire in 1517 with Martin Luther's 95 Theses. Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) was a Catholic monk and theologian who only issued the theses as an invitation to fellow clerics to debate the issue of the sale of indulgences. Indulgences were writs guaranteeing one's soul (or that of a loved one) a shorter stay in purgatory after death, and Luther objected to their sale as well as to the pope's authority over souls in purgatory and the apparent greed behind the policy. In objecting to the sale of indulgences, Luther challenged the authority of the pope and, therefore, the Church.

The Church responded by excommunicating Luther in 1521 and branding him a heretic and an outlaw at the Diet of Worms, but by that time, his 95 Theses and other works had been published, widely circulated, and translated from Latin into the vernacular. Other priests, such as Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531), initiated their own challenges, and the Reformation spread in Switzerland and then France. In June 1530, the Diet of Augsburg was convened by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556), in an attempt to reunify the Church. The Lutherans presented the Augsburg Confession (written by Philip Melanchthon, Luther's right-hand man, l. 1497-1560) while the Catholics offered the Confutatio Augustana (mainly written by Johann Eck, l. 1486-1543). Neither party accepted the confessions of faith of the other, and nothing was resolved.

Pope Paul III and Charles V made another attempt at reconciliation of Catholics and Protestants in 1537, but this meeting was never convened due to the military conflicts between Charles V and King Francois I (Francis I of France, r. 1515-1547). Charles V was still anxious to effect some form of reconciliation, not only because of the civil unrest and violence that accompanied the Reformation but because he needed his subjects united against a possible invasion by the Ottoman Empire. This next attempt was scheduled for 13 December 1545 in Trento (anglicized as Trent), Northern Italy.

First Session

Although it was called as an ecumenical conference, the Catholic contingent barred Protestants from voting or having any meaningful voice in the proceedings from the beginning. In response, Protestant clergy refused to attend (even though some, like Melanchthon, made initial attempts). The Council of Trent then became a Catholic conference whose goal was to reform the abuses of the Church (like the sale of indulgences), address claims of error in Church teaching and practice, and affirm (or reaffirm) the Church's authority and centrality in the lives of the people.

The Protestant Reformation may never have happened – or certainly would have developed differently – if the Church had simply considered Luther's early objection to the sale of indulgences instead of trying to silence him. As it was, however, he proceeded from that criticism to a rejection of the Church entirely, and central to his claim was that one was justified before God by faith alone and for communion with God one needed only the Bible. The Church claimed that one was justified by one's faith and the works which proceeded from that faith, citing the biblical book of I Corinthians 15:58, "Abound in every good work, knowing that your labor is not in vain in the Lord," and other similar passages. Luther responded with his own biblical texts, including, "For by grace you have been saved, through faith; and this not of yourselves, it is the gift of God, not of works, lest any man should boast" (Ephesians 2:8-9). The first issue to be addressed, therefore, was how one was justified in the eyes of God.

In order to fully address that concern, however, they had to first unanimously agree on what books of the Bible constituted Holy Scripture. The Lutherans had rejected certain books and, by this time, Luther had published his own translation of the Bible, and to counter this, an 'authoritative' version of scripture had to be decided on. This was concluded in April 1546 when the Vulgate translation of Saint Jerome was affirmed as the only authoritative text. By June 1546, they had unanimously agreed on the truth of the original sin which separated the soul from God and made justification necessary at all. They reached their conclusions on justification in January 1547 after months of debate. Scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch comments:

The Council rejected Luther's assertion that sinful humanity cannot fulfil the Law – "God does not command impossibilities". God's grace is available through the good works which humans can perform, including participation in the Church's sacraments of baptism and penance (in March 1547 all seven sacraments of the medieval Western Church were reaffirmed as "instituted by Jesus Christ")…the long and intricately balanced text of the Decree on Justification was finally passed in January 1547. (235-236)

In March 1547, the council also agreed on the spiritual necessity of infant baptism (a rejection of the claim of the Anabaptists that only adult baptism was valid) and the importance of and rites concerning confirmation in the Church. Further sessions were interrupted due to the plague, and, although there were meetings, no other decrees were issued, and the council was prorogued in September 1549.

Decrees & Canons of First Session

The first session issued a number of decrees (edicts) and canons (rules or laws) which reaffirmed Church teaching and practice while rejecting and condemning Protestant claims (it also reaffirmed and approved Pope Paul III's 1542 creation of the Holy Office, better known as the Inquisition). The decrees focused primarily on justification and how the Church's teachings provided the spiritual guidance for the soul to merit eternal life in heaven while Protestant works led one astray and would lead the soul to hell after death. The decrees included:

- The Impotency of Nature and the Law to Justify Man – People are born in sin and unable to abide by God's law.

- The Dispensation and Mystery of the Advent of Christ – Christ came as an intercessor between humanity and God.

- Who Are Justified Through Christ – Although Christ died for all people, only those who accept him will be justified (saved).

- A Description of the Justification of the Sinner and its Mode in the State of Grace – The transition from sin to salvation through the 'born again' experience offered by the Church through the sacraments.

- Against the Vain Confidence of Heretics – The claim that one only needed faith and the Bible to be justified is untenable because one is relying on one's own will and judgment to declare one's salvation instead of the established authority of the Church.

- The Fruits of Justification/Merits of Good Works – One is saved, not by faith alone, but by the good works that faith inspires. By performing good works, one glorifies God and announces one's salvation. (Janz, 406-411)

The other decrees also had to do with justification directly or indirectly, and the canons followed this same paradigm but were a careful and direct rejection of Protestant theology, criticisms, and practice. Each canon concludes with the statement, "Let him be anathema," meaning "cursed," excommunicated from the Church, and doomed to hell. They primarily target the Lutheran claim that faith alone and scripture alone are all one needs to be saved.

Drawing on Proverbs 3:5 – "Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and lean not on your own understanding" – the Council determined that Protestants were relying on their own judgment as to what constituted salvation and were rejecting any trust in God by denying the authority of the Church which claimed direct commission from Jesus Christ. Two examples of canons going directly to this point are 13 and 14:

Canon 13: If anyone says that, in order to obtain the remission of sins, it is necessary for every man to believe with certainty and without any hesitation arising from his own weakness and indisposition that his sins are forgiven him, let him be anathema.

Canon 14: If anyone says that man is absolved from his sins and justified because he firmly believes that he is absolved and justified, or that no one is truly justified except him who believes himself to be justified, and that by this faith alone absolution and justification are effected, let him be anathema. (Janz, 413)

The canons condemned the Protestant Reformation as heresy and its supporters as heretics. The underlying warrant (authority) for the Church's argument was that if anyone could claim to know 'truth' simply by concluding that what they knew was truth, then there was no truth, only individual opinion. Further, if anyone who could read the Bible could interpret it for themselves, there was no 'true' understanding of scripture possible, only individual interpretations. Since it was understood that people were born into sin and their will corrupted, one could not rely on one's own insight to interpret scripture but should adhere to the written works of the Church Fathers and traditional understanding and practice.

Second & Third Sessions

The second session convened in May 1551 under Pope Julius III (served 1550-1555) with the goal of resolving questions concerning the Eucharist. Some Protestant sects (beginning with Zwingli in Switzerland) claimed the celebration of the Mass was only a memorial of Christ's sacrifice and denied that God was present in the consecration or that the bread and wine were transformed into Christ's body and blood. The Council rejected this as heresy and decreed that Christ was substantially present in the Eucharist, condemning anyone who disagreed in Canon 1 from 1551:

If anyone denies that in the sacrament of the most holy Eucharist are contained truly, really, and substantially the body and blood together with the soul and divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ, and consequently the whole Christ, but says that he is in it only as in a sign, or figure or force, let him be anathema. (Janz, 416)

They proceeded along the same lines with penance and extreme unction, maintaining that these rites, as with the others, were instituted by Christ himself and could not be denied without placing one's soul in peril of eternal damnation. The session was set to continue on to other subjects, but it was prorogued when the Protestant prince Maurice, Elector of Saxony (l. 1521-1553), formerly an ally of Charles V in the Schmalkaldic War (1546-1547), deserted him to ally with the French King Henry II in 1552 in the Second Schmalkaldic War.

The Council next convened under Pope Pius IV (served 1559-1565) in January 1562. This session dealt primarily with reforming abuses in the Church, including poorly educated clergy who lived off tithes of parishioners without providing spiritual guidance or comfort. Decrees were issued for establishing seminaries and reforming the requirements for clergy. Ignatius of Loyola (l. 1491-1556) had already formed his Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in 1534 and, once approved by the pope, had begun an initiative regarding education which, by 1562, had taken root and spread. The Council approved the establishment of more seminaries and more in-depth study by clerical candidates in 1563.

In response to the Protestant claim that clergy could marry, the Council maintained that neither Christ nor his apostles were married and noted that Saint Paul had addressed the issue in the biblical passage, "It is good for them to stay unmarried, as I am" (I Corinthians 7:7). It was decided that the clergy would follow Paul's suggestion and example and remain unmarried. The Protestant objection to the sale of indulgences was addressed in that the writs would no longer be sold but could be had for a donation, and the process would be regulated. Protestant rejection of icons and religious art was condemned, as well as their objection to the veneration of the saints and relics.

In countering the iconoclasm of the Protestants, the Council approved the commissioning of religious art and musical compositions (George Frideric Handel's Messiah is a direct result of the Catholic Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent), which gave birth to the baroque style. Catholic churches would henceforth be grander and more elevating than the modest Protestant houses of worship, and the architecture, art, and music would work together to bring a congregant into a closer relationship with God and the Church. Music, especially, was to be used to celebrate the sacred mysteries of faith and encourage one to open oneself to divine joy and contemplation of the wonder and majesty of God.

At the same time, to prevent the spread of Protestant thought, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Prohibited Books), created in 1559, was approved by a decree in 1563, which began by specifically naming the works of Reformers such as Luther, Zwingli, John Calvin (l. 1509-1564), and others. The Index was detailed in its prohibitions but, essentially, stated any book condemned by the pope or Holy Office or by one's priest or bishop was to be rejected by a Catholic in good standing with the Church. Unrepentant reading of books on the Index was understood as a grave sin and an act of rebellion that imperiled the soul. The Index continued in effect until 1967 when it was suspended.

Conclusion

The delegates who established Church doctrine and issued the decrees of the Council of Trent were not representative of the whole Catholic clergy at that time. Delegates from France only participated in the third session, German delegates made uneven appearances, and most of the decisions were made by Italian clergy who lived in relative proximity to Trent and had an easier time traveling for meetings. Even so, their decrees were met with approval, and the petition to ratify the decrees was granted by Pope Pius IV in January 1564.

The decisions, decrees, and canons of the Council of Trent became the blueprint for the Catholic Counter-Reformation, which reestablished the Church's authority through clear rules, regulations, and definitions of what it meant to be Catholic. The Council essentially upheld all of the policies and traditions of the medieval Church while reforming any of their abuses as well as errors in policy. Having addressed these problems, the Council affirmed the Church's primacy as the sole authority of the Christian vision. Although some of the decrees, such as the Index, have since been suspended, the decisions of the Council of Trent continued to inform Catholic belief and practice up through the 1960s and, in part, continue to in the present.