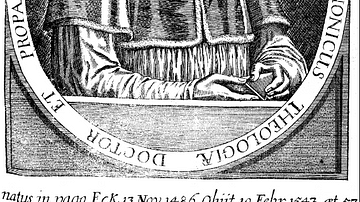

Johann Eck (l. 1486-1543) was a Catholic theologian and writer best known for his disputations with Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) beginning in 1517 and continuing until his death in 1543. Eck maintained the position that, if anyone could determine truth for themselves, then there was no truth, only opinion; a claim that became central to the Counter-Reformation.

Eck and Luther were friends until Luther published his 95 Theses in October 1517 and, from then on, were famous adversaries. He was the first to attack the 95 Theses in 1517, argued with Luther in print throughout 1518, and debated Luther and Andreas Karlstadt (l. 1486-1541) at Leipzig in 1519 where, although no winner was called, Eck was privately congratulated for his victory. He had clearly won over Karlstadt and forced Luther to publicly admit his challenge to papal authority leading to Luther’s excommunication in 1521.

As a leading faculty member at the University of Ingolstadt, Eck instituted the policies prohibiting the study of Lutheran works which included anything by Karlstadt, Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560), Martin Bucer (l. 1491-1551) or any of their supporters. In 1523 these policies led to the arrest of the young scholar Arsacius Seehofer (l. c. 1504 - c. 1539) at Ingolstadt who had presented a lecture on Melanchthon’s works. His arrest prompted the Lutheran activist Argula von Grumbach (l. 1490-c. 1564) to write her famous To the University of Ingolstadt defending Seehofer.

Between 1522-1526, Eck published at least eight major works in addition to letters denouncing the movement that came to be known as the Protestant Reformation and defeated the Reformer Johann Oecolampadius (l. 1482-1531) in public debate in June 1526. At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530 he represented the views of the Church against Melanchthon and the Lutherans, presenting his compilation of 404 heresies and contributing to the Pontifical Confutation of the Augsburg Confession, denouncing the Reformation and clarifying the Catholic confession of faith. In 1537 he published his own translation of the New Testament to counter Luther’s earlier translation and, in 1540, was a leading figure at the Colloquy of Worms which tried, unsuccessfully, to work out a compromise between Catholics and Protestants.

He died of fever in 1543 but his works informed the proceedings of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) and the Counter-Reformation (1545 - c. 1700) which formally denounced the Protestant sects as heresy and reestablished the authority of the Catholic Church. Although Protestant writers presented him in a negative light, he remains highly esteemed by Catholics and is recognized today as one of the greatest theologians and public speakers of his time and one of the very few who were a match for Martin Luther.

Early Life & Education

Johann Eck was born Johann Maier von Eck in the village of Eck in Swabia, Bavaria in 1486. Nothing is known of his mother but his father, Michael Maier, was the town magistrate. His uncle, Martin Maier, was the parish priest at Rottenburg am Neckar and took the boy in to educate him. No reason is given for Eck’s move to his uncle’s house and there are no records of any siblings. In 1498, at the age of twelve, Eck was enrolled at Heidelberg University where he studied for a year before moving to Tubingen where he was awarded his master’s degree in 1501 before moving on to Cologne and then Freiburg for further study.

By c. 1505, when he was nineteen years old, he was fluent in Latin, Hebrew, and Greek and had mastered the disciplines of mathematics, jurisprudence, philosophy, and theology. His advanced studies had been financed by his uncle who, around this time, cut off his allowance for unknown reasons and Eck supported himself through tutoring. He continued his studies at Freiburg, where he was appointed rector, and was ordained a priest in 1508. His ordination was granted by a papal dispensation (as he was too young to be eligible) recognizing his intellectual achievements and devotion to the Church. In 1510 he received his Doctorate in Theology at the age of 24 and was invited to take the post of Professor of Theology at the University of Ingolstadt where he was appointed pro-chancellor in 1512.

During his early years at Ingolstadt, he wrote a number of works on philosophy, geography, and theology. His theological works became standard texts at Ingolstadt and elsewhere and he was already well known as a scholar and writer by the age of 28.

Eck & Luther

Eck had embraced the philosophy of Humanism while in school at Tubingen and, at some point, (probably at Heidelberg) had met and become friends with the Humanist scholar and jurist Christoph von Scheurl (l. 1481-1542). In 1517, von Scheurl introduced Eck to Martin Luther, a professor at Wittenberg where von Scheurl had taught law. Von Scheurl no doubt thought the two of them would bond over their shared admiration for Humanist thought and religious devotion and seems to have been right as later documentation notes that Eck and Luther initially regarded each other highly.

In October 1517, Luther posted his 95 Theses condemning the Church’s policy of the sale of indulgences and Eck responded with a brutal refutation which left Luther “deeply hurt by what he saw as a personal betrayal” and he “retaliated with anger” (Roper, 84). Eck responded to the retaliation in kind, and this marks the beginning of the decades-long feud between the two former friends.

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses were quickly printed and distributed throughout 1518 during which time Eck consistently argued against them. Karlstadt had come out in support of Luther and Eck challenged him to debate on the condition that Luther, should he be present, remain silent. Luther responded with a letter to Karlstadt, clearly actually addressing Eck, expressing his interest in debating Eck anytime.

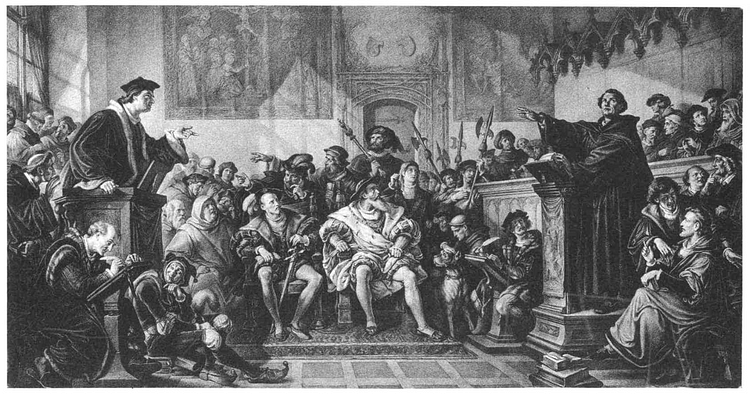

The Leipzig Debate

The debate was set for June-July 1519 at Pleissenburg Castle in Leipzig and would be presided over by George, Duke of Saxony (r. 1500-1539), who supported Eck against the Reformation. Eck invited Luther to participate but still with the stipulation he could not engage in the debate with Karlstadt. Although Karlstadt argued well, Eck was the superior debater and, even though he may have technically lost, was able to confuse his opponent well enough to be declared the winner.

After Karlstadt, Luther took the floor and, after arguing various topics, the debate came down to the authority of the Church as led by the pope and directed by learned councils. When Luther insisted that faith alone and scripture alone were all one needed for communion with God, Eck attacked him as a Hussite, one of the followers of Jan Hus of Bohemia (l. c. 1369-1415), who had been condemned for heresy by the Council of Constance in 1415 and burned at the stake. Luther at first rejected the label but then argued that some of Hus’ points had been valid and that his claims were not the “Bohemian virus” the Church regularly dismissed them as. Scholar Roland H. Bainton recreates Eck’s response from the original transcripts:

But this is the Bohemian virus, to attach more weight to one’s own interpretation of Scripture than to that of the popes and councils, the doctors and universities. When Brother Luther says that this is the true meaning of the text, the pope and councils say, `No, the brother has not understood it correctly.’ Then I will take the council and let the brother go. Otherwise, all the heresies will be renewed. They have all appealed to Scripture and have believed their interpretation to be correct and have claimed that the popes and the councils were mistaken, as Luther now does. (107)

Luther responded that he would assert the truth as God had revealed it to him and it did not matter whether popes or councils or universities agreed with that truth. When pressed, Luther then had to admit publicly that he challenged the authority of the pope and disagreed with the verdict of the Council of Constance that had condemned Hus. No verdict was given on the debate as George, Duke of Saxony seems to have become bored with the discussion and needed the hall cleared for another event.

The debate continued in print with Eck and Luther attacking each other in open letters, pamphlets, and longer works. In 1519, Eck published major works denouncing Luther’s theology and the Reformation movement while also advocating for the banning and burning of Protestant books. He also appealed directly to Rome, resulting in Pope Leo X issuing the Papal Bull Exsurge Domine refuting Luther’s claims as errors. Eck personally carried the bull back to Saxony in July 1520, read it in public, and had it posted but, by this time, popular opinion had sided with Luther and Eck was attacked and driven from town after town. Luther burned the bull and, in January 1521, was excommunicated.

Defender of the Faith

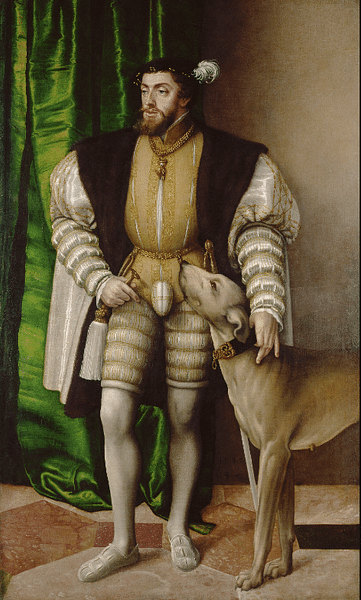

Eck was not foolish enough to believe the ex-communication would silence Luther and continued his attack in 1521 encouraging Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, to call the Diet of Worms at which Luther was ordered to appear. Luther’s Speech at the Diet of Worms (known as the 'Here I Stand' speech) in April 1521 made his position clear and Eck appealed to Charles V to take harsher measures, resulting in the Edict of Worms of May 1521 declaring Luther an outlaw who could be killed without consequences. Luther was secretly kidnapped by a noble supporter, Frederick III (the Wise, l. 1463-1525) and brought safely to his castle at Wartburg seeming to disappear at first until he began publishing more of his works, including his translation into German of the New Testament.

Eck retaliated by imposing a ban on all works by Luther and any of his supporters at Ingolstadt by 1522 and invited officers of the Inquisition to examine anyone suspected of reading or distributing such works. In 1522, the scholar Arsacius Seehofer was warned by Eck against introducing Lutheran doctrine to the school which Seehofer ignored, delivering a lecture on Melanchthon’s theology in the spring of 1523. Eck had Seehofer censured and, when a search of his apartment turned up 17 Lutheran texts, he was expelled, arrested, and threatened with execution unless he recanted. This event inspired Argula von Grumbach’s To the University of Ingolstadt, an open letter condemning the faculty for persecuting Seehofer and demanding they explain how Luther’s or Melanchthon’s views were heretical as they were drawn directly from the Bible.

Eck and the other faculty ignored the letter and so von Grumbach had it published at the urging of a fellow Protestant and reformer, Andreas Osiander (l. 1498-1552), who wrote a preface to the piece. The pamphlet became a best-seller, encouraging von Grumbach to write further, and may have helped secure Seehofer’s release in 1524. Eck continued to ignore von Grumbach as he continued his attacks on Luther, but her arguments were certainly dealt with in the works he continued to publish against the Reformation through 1526 and included refutations and condemnation of Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) and his followers as well as the Anabaptist movement. That year (1526), he debated Oecolampadius and was declared the victor, continuing to base his essential argument on the claim that if every individual who read the Bible could then say they understood the ultimate truth and Will of God, then there was no truth, only opinion.

When the Diet of Augsburg was convened in 1530, Eck compiled his 404 articles on the errors of the Reformers and submitted them to Charles V with a cover letter:

All Catholics believe that, in the midst of these numerous tumults of wars and afflictions of Christianity, you, most worshipful Emperor, are the divinely appointed, chosen, and consecrated instrument of stopping the decline of the Catholic faith, for helping the afflicted Church and the oppressed ecclesiastics, for saving the Christian empire from the Turk…

But Martin Luther, the Church’s enemy within the Church, has refused to heed the high admonitions addressed to him by your Majesty and hurled himself into a veritable whirlpool of godlessness. He blasphemes God; he has no reverence for saints or sacraments and no respect for ecclesiastical or secular magistrates; he is contumelious and rebellious; he kindles the fires of sedition throughout the empire; he is making ardent preparations for a deluge of Christian blood; he is arming the hands of the Germans in order that they may bathe in the blood of the Pope and Cardinals.

Thus, he has produced a vast offspring, much worse than himself, bringing forth broods of vipers. They destroy the churches, demolish the altars, and trample upon the most holy Eucharist; they burn images of Christ and the saints, extinguish the worship of God, cast the relics of the saints into the dirt, and steal the church’s treasures…

For the purpose of stamping out their deceitful vaunts, I present myself before your most worshipful Majesty, ready to perform the same service that I performed at Leipzig against Luther and at Baden against Oecolampadius, namely, to defend all the ordinances, usages, doctrines, and ceremonies of our Catholic religion and faith and to attack the arguments of the antagonists. Let them come on, these enemies of the church, these instruments of godlessness, these advocates of heresies, and vessels of iniquity. (Lindberg, Source 8.10, pp. 143-144)

At the Diet of Augsburg in June 1530, Melanchthon presented the Lutheran Augsburg Confession of faith which was approved by the Protestant princes in attendance. Eck contributed to the Pontifical Confutation of the Augsburg Confession, rejecting Melanchthon’s work while asserting the beliefs of the Catholic Church.

Conclusion

Between 1530 and 1542, Eck continued his attacks on the Reformation movement while defending the authority and traditions of the Catholic Church. In 1542, a rumor circulated that he had died. Scholar Lyndal Roper comments:

In 1542, Luther’s old enemy Eck had been one of those fortunate (or unfortunate) individuals able to read their own obituaries. Believing that their antagonist was dead, Bucer had written a tract against him, and Eck responded with a counterblast, boldly affirming on the title page that he was very much alive. But just days after his riposte had appeared, Eck fell into a fever, soon becoming delirious. Insisting that it was too early to call a priest, he grew increasingly incoherent, and when the priest was finally summoned Eck could no longer follow the words of the rite. (391-392)

He died in early 1543. Luther, who would die three years later, seized on Eck’s sudden exit, which he suggested denied him the Last Rites since he could not understand them, as God’s judgment for his old adversary’s endless persecutions. He concluded Eck had gone straight to hell just as he had done with Zwingli in 1531 when the latter fell in battle in the Kappel Wars. Eck was mourned by the Catholic community, however, as a defender of the faith and a champion of traditional religious belief.

In the present day, Johann Eck is always featured in any film or documentary on Martin Luther as the villain of the piece, persecuting Luther and his brave followers for their convictions while hiding behind the traditions of the Church. This depiction is unfair and inaccurate, however, as Eck proved himself as courageous as any of the reformers and was recognized, in his time, as the most distinguished theologian, intellectual, writer, and public speaker in the Holy Roman Empire.

His work informed the Counter-Reformation which reestablished the authority of the Church and reformed its abuses and, most importantly, his central argument was never refuted: If anyone’s interpretation of the Bible is valid based on their faith in that conviction, then no one’s is because there is no longer any authority to determine validity. If truth is only opinion, then there is no Truth. Eck’s argument was proven correct as Protestant sects proliferated throughout the 16th century, each one claiming they alone represented true Christianity.