Johann Strauss II (1825-1899), aka Strauss the Younger, was an Austrian composer best known for his waltzes such as The Blue Danube. Famed throughout Europe and the United States in his own lifetime, Strauss was known as the 'Waltz King', but he also wrote many polkas, marches, quadrilles, and operettas such as Die Fledermaus and Der Zigeunerbaron.

Early Life

Johann Strauss Junior was born in Vienna on 25 October 1825. His mother was Anna Streim, and his father was the successful composer Johann Strauss the Elder (1804-1849), who wrote the Radetzky March besides many waltzes, polkas, and galops (a fast dance which included a hop after each phrase of music). Strauss Senior had his own orchestra which played at prestigious venues in Vienna and on tours across Europe, even participating in the celebrations that marked the coronation of Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901) in June 1838. Johann Senior was appointed the Imperial Director of Court Dance Music (a title his eldest son would inherit from him).

Johann Junior, surrounded by the heady success of his father, walked right into a musical career of his own but one that would far outshine his father's. He had to make a rather secretive start, though. Johann Senior did not want his eldest son to learn the violin, and so Johann, while appeasing his father's wishes by working as a bank clerk, learnt the instrument in secret (from his father's band leader of all people). Johann Senior was, fortunately for posterity, not successful in limiting his son's choices, and even Johann's younger brothers Josef Strauss (1827-1870) and Eduard Strauss (1835-1916) became talented musicians and minor composers. Johann Strauss Senior left his wife and the family home in 1842, which at least meant that Johann Junior could now openly study music.

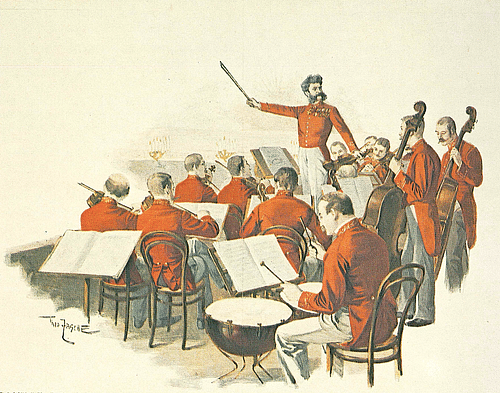

Since he could not join his father's orchestra, Johann Junior decided in 1844 to form his own orchestra in Vienna. Both Strausses were establishing a fanbase in a phenomenon that would become commonplace later in the century: people came especially to hear the conductor. Johann Junior's first contract was at Dommayer's Garden Restaurant, and it is significant that he closed his first public concert with his father's composition, Lorelei-Rheinklänge. Johann Junior's concerts met with rave reviews, and the success finally allowed father and son to reconcile their differences.

Johann Strauss Senior died in 1849 of scarlet fever; he was only 45 years old but had literally worked himself to death with his prolific concert tours. Aged 24 at the time, Johann Junior decided to merge his own orchestra with that of his late father. Johann, Josef, and Eduard all took turns conducting what became known as the Strauss Family Orchestra. Johann was so successful he was soon running six orchestras to cover as many venues in Vienna as possible; he would dash between them to make a brief conducting cameo at all six. It seemed the Strausses would take some dethroning as the musical masters of Austria.

Polkas, Marches, & Waltzes

Like his father, Johann was particularly attracted to the trio of waltzes, polkas, and marches. The lively polka, which derived from a Bohemian folk dance, is a duple-time (2/4) dance whose popularity is almost entirely down to the Strauss family. Marches were composed for playing as an aid for soldiers to march in moderate or quick time, hence its two-step rhythm. Johann was also interested in quadrilles which are an intricate form of group dancing with an equal number of couples. Again, the Strausses made quadrilles popular for a time, but the difficulty of the steps meant the dance soon went out of fashion.

The waltz is a triple-time (3/4) dance influenced by the Landler, an 18th-century Austro-German folk dance popular in Alpine communities. The 'waltz' name likely comes from a corruption of the French dance which involved much turning, the volta. In England, the volta was known as 'lavolta' and in German-speaking countries as 'volter'. The waltz was a more sophisticated version of this dance (and quite possibly others) where the usual throwing of one's female partner in the air and nimble footwork were replaced by an emphasis on gliding across the dance floor where everyone stayed on the ground. Despite the sophistication, the waltz still shocked many since the partners remained in close proximity throughout. As with most new fashions which rankled with the elder generations, young people of all classes loved it.

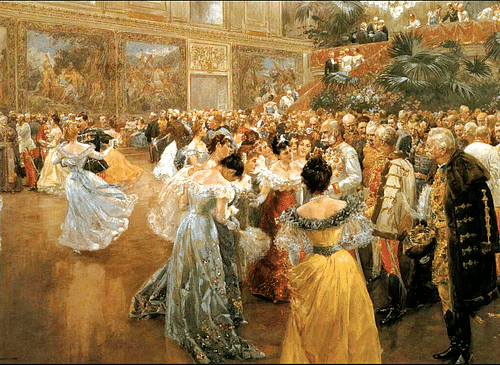

The waltz had arrived in the 1770s, but the dance became immensely popular in the 19th century, not only with the well-to-do in their chandeliered ballrooms but also with the working classes in beer halls. Strauss' waltzes seemed made for the times, a period when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was at its cultural peak and when, for many, Vienna was the musical capital of Europe. Political, economic, and military matters were an entirely different story. The ruling Habsburgs struggled to deal with a stock market crash and the threat of a rising Prussia, and in many ways, Strauss' music was a source of escapism that helped mask the cracks appearing in the fragile empire.

Vienna's famous Musikverein concert hall opened its doors in 1870. The home of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, after the premiere of Strauss' waltz, Freuet euch des Lebens (Enjoy Life), the hall swiftly became a temple of waltzes and Vienna the home of the dance. The music historian P. Gammond notes the following peculiarity of Viennese waltzes:

The Viennese waltz developed the characteristic of a slight anticipation of the second beat of the bar, a device known as the Atempause (literally, ‘breathing space'), which gives a delightful and distinctive lilt to the playing.

(Arnold, 1966-7)

Johann Strauss carried on where his father left off and rose to new heights of popularity; his success was simply enormous. As early in his career as 1852, a visiting French journalist noted that "in every house, on every piano in Vienna lie Strauss waltzes" (Schonberg, 347). Strauss' personal life was more problematic. He married three times in his life: in 1878 to Henrietta Treffz ('Jetty'), a singer, and after her death, an actress, Angelika, who then left him after nine years, and finally Adele, a Jewish widow. The latter marriage was an interfaith one and so prohibited under Austrian law. Strauss got around the problem by renouncing his Austrian citizenship, becoming a citizen of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, and marrying Adele in what is today Romania.

The Blue Danube

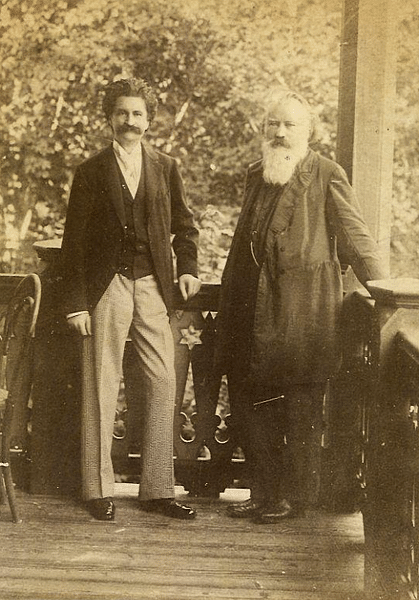

Strauss' waltz masterpiece is An der schönen, blauen Donau (By the Beautiful Blue Danube), most often referred to simply as The Blue Danube. The most famous waltz of all those written by 'The Waltz King' was composed in 1867 and performed with great success at the Paris Exhibition ball that year. The Blue Danube swept Vienna off its feet, even that most serious of 'serious' composers Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) admired it and its creator, once saying of Strauss, "There is a master of the orchestra, so great a master that one never fails to hear a single note of any instrument" (Schonberg, 353).

Strauss' fame grew as he toured Europe with his orchestra; he was particularly popular in St. Petersburg. By the 1870s, Strauss' reputation had crossed from Europe to the Americas. He toured the United States in 1872. Contracted for 14 concerts for a huge fee, Strauss was as popular in America as anywhere else. One New York newspaper reported: "Johann Strauss, the waltz king, personally is evidently a good fellow. He talks only German but he smiles in all languages" (Schonberg, 354).

One memorable American concert was held in Boston on 17 June when Strauss conducted the largest orchestra ever created. The event was the World Peace Jubilee, and to conduct the 1,087 musicians and 20,000 singers in front of him, Strauss required a special illuminated and extra-size baton and 20 assistant conductors. Perhaps rather predictably, the difficulty of ensuring so many musicians were all playing as one meant that the quality of the music suffered somewhat. Strauss described the experience:

Now just conceive of my position, face to face with a public of 100,000 Americans. There I stood at the raised deck, high above all others. How would the business start, how would it end? Suddenly a cannon shot rang out, a gentle hint for us 20,000-odd to begin playing The Blue Danube. I gave the signal, my twenty assistant conductors followed as quickly and as well as they could, and there broke out an unholy racket such as I shall never forget. As we had begun more or less together, I concentrated on seeing that we should finish together, too. Thank heaven, I managed it! (Schonberg, 354-5)

Operettas

Strauss was encouraged to try his hand at operettas by both his wife Henrietta and his friend and fellow composer Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880). Operettas are shorter and lighter versions of operas, with entertainment a high priority for the composer and librettist. For this reason, operettas came to represent works of comedy or satire. The format became popular in the mid-19th century. Strauss wrote 17 operettas and ballets. His first operetta was Indigo based on the adventures of Ali Baba, but most of his work in this genre is plagued by terrible librettos, with Strauss often focussing entirely on the music side of the performance. In amongst the mediocrity were two outstanding works: Die Fledermaus (The Bat) and Der Zigeunerbaron (The Gypsy Baron), first staged in 1874 and 1885, respectively.

Die Fledermaus' libretto is based on the French play by Meilhac and Halévy, Le Réveillon, which, as its title suggests, is set at a lavish party on Christmas Eve. Even better for Strauss, the play contains a magnificent ball scene – right down his street in terms of musical composition. Once the libretto was ready, Strauss shut himself away for six weeks to write the score. Perhaps unsurprisingly, when the public saw Die Fledermaus at its premiere on 5 April 1874, they were treated to a rousing waltz Overture.

In Der Zigeunerbaron, Strauss combines his flair for Romantic music with Hungarian folk music roots and comedy with Viennese urbanity. The story tells of a landowner who marries a gypsy girl only to find out that she is actually the daughter of a Turkish ruler. The operetta was immensely popular in German-speaking countries, receiving well over 7,000 performances in the first 40 years after its debut.

Strauss' Major Works

The most popular works of Johann Strauss II include:

- Tritsch-Tratsch polka (1858)

- Champagner-Polka – Champagne Polka (1858)

- Morgenblätter waltz – Morning Newspapers (1864)

- An der schönen, blauen Donau waltz – By the Beautiful Blue Danube (1867)

- Künstlerleben waltz – An Artist's Life (1867)

- Geschichten aus dem Wienerwald waltz – Tales from the Vienna Woods (1868)

- Unter Donner und Blitzen polka – Thunder & Lightning (1868)

- Wein, Weib und Gesang waltz – Wine, Women and Song (1869)

- Freuet euch des Lebens waltz – Enjoy Life (1870)

- Wiener Blut waltz – Vienna Blood (1873)

- Die Fledermaus operetta – The Flittermouse or The Bat (1874)

- Rosen aus dem Süden waltz – Roses from the South (1880)

- Frühlingsstimmen waltz – Voices of Spring (1882)

- Der Zigeunerbaron operetta – The Gypsy Baron (1885)

- Kaiser-Walzer – Emperor Waltz (1889)

Death & Legacy

Johann Strauss II died of lung problems in Vienna on 3 June 1899; he was interred in the Central Cemetery of Vienna. Strauss had produced what is often disparagingly called 'light' music, but he was a product of his period when there was a reaction to the 'serious' music which had gone before. As the Classical Music Encyclopedia notes: "The operettas and waltzes of Offenbach and Johann Strauss the Younger probably contributed more than anything else to the serious business of deliberately not being serious about the second half of the nineteenth century. Their punishment was eventual respectability and, for a time at least, undeserved historical neglect. But their reward was phenomenal social success" (326).

Besides Brahms already mentioned, other composers who rated Strauss included Richard Strauss (no relation, 1864-1949) who once wrote that "Of all the God-gifted dispensers of joy, Johann Strauss is to me the most endearing…I respect in Johann Strauss his originality…As for the Rosenkavalier waltzes…how could I have composed those without thinking of the laughing genius of Vienna" (Schonberg, 355). Meanwhile, Maurice Ravel (1875-1937), described his La Valse as "a sort of homage to the memory of the Great Strauss, not Richard, the other – Johann" (Steen, 542-3). More immediately, Strauss' work influenced fellow-Austrian composer Franz Lehár (1870-1948) who, as a prolific writer of waltzes and operettas, was seen as Strauss' successor by the Viennese.

The symphonic-like quality of many of Strauss' grander waltzes has ensured they remain a favourite of orchestras and concert audiences alike around the world, even though few people are dancing to them anymore. The music clearly can stand on its own in performance without any quick turning feet needed. Representing the glamour, charm, and romance of a Vienna long gone, Johann Strauss' music is famously showcased each year in the most watched musical concert of them all, the Vienna New Year's Concert seen by tens of millions every 1 January.