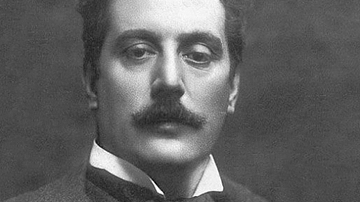

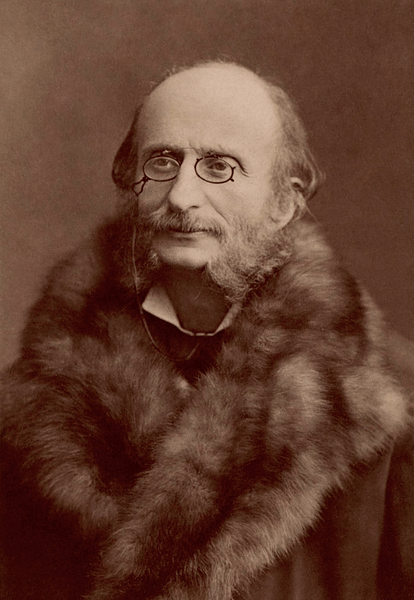

Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) was a composer of German birth who took French citizenship and became famous in Paris for his comic operettas, a genre he created, and for the more serious opera, The Tales of Hoffmann. A virtuoso cellist, conductor, and prolific composer of stage works, Offenbach was hugely popular across Europe through the 1860s.

Early Life

Jakob Eberst was born in Cologne, Germany, on 20 June 1819; his new family name of Offenbach was adopted later and derived from his grandfather's hometown of Offenbach am Main near Frankfurt in central Germany. His father, Isaac, was a leader of prayer and music in a synagogue. Jakob learnt to play the violin from age six and then the cello from age nine.

Jakob moved to Paris with his father and brother Julius in 1833. Jakob, now known as Jacques, was good enough to attend the Paris Conservatoire but he studied there only for one year. Living the bohemian life of Paris, his first job was in the orchestra of the Opéra-Comique. He paid for private lessons in composition from Fromental Halévy (1799-1862). In his spare time, Offenbach composed pieces for cello and piano, as well as a host of sentimental ballads, many of which were performed in salons in the French capital. Offenbach became best known as a virtuoso of the cello, but he also had a few waltzes played by the outdoor orchestra in the Jardin Turc. His career ticked along through the 1840s, but things took an upturn from 1850 when he became the conductor at the Théâtre Français.

Character & Family

The historian C. Schonberg gives the following rather uncomplimentary appraisal of Offenbach's physique and character:

Offenbach to the end was a citizen of the boulevards rather than a citizen of Paris. He was at home among the eccentrics about him, too. He was nearsighted (blind without his glasses), skinny, with an enormous nose, and long, wavy hair. He looked like an intelligent scarecrow with the head of a parrot.

(356)

In 1844, Offenbach married Herminie, the daughter of Madame Mitchell, a Spaniard and celebrated salon host in Paris. Offenbach was only given consent to marry by Herminie's parents if he converted to become a Catholic and earned some money by doing a concert tour in England; Offenbach did both. The couple had one son and four daughters together. In the 1860s, Offenbach also had a regular mistress, the singer Zulma Bouffar, with whom he had two children.

Opera as Musical Comedy

In the summer of 1855, Offenbach decided to promote his own work, mostly short comic pieces, by renting out the Théâtre Marigny, located on Paris' main avenue, the Champs-Elysées. Offenbach explains in his autobiography why he took this decision:

It occurred to me that comic opera was no longer found at the Opéra-Comique; that really funny, gay, witty music was gradually being forgotten…it is then that I got the idea of starting a musical theatre myself, because of the continued impossibility of getting my work produced by anybody else. (Schonberg, 357)

The theatre was renamed Bouffes-Parisiens to reflect its repertoire of opéra-bouffe. The genre of opéra-bouffe (aka opera buffa) was initially based on everyday life characters finding themselves in comic situations. Early examples include Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791). It is part of the wider genre of comic opera, the opposite of serious opera (opera seria) and distinguished from the latter by its retention of portions of spoken dialogue and the avoidance of more serious themes in the story. Opéra-bouffe usually involved scenes of romantic farce. A journalist for the New York Times, writing in 1876, noted that "The opéra-bouffe is simply the sexual instinct expressed in melody" (Wade-Matthews, 393). From this type of opera there developed works which have become known as operettas, which are light operas, include spoken dialogue, and often contain specifically inserted stand-alone tunes played alongside a dancing sequence of no particular relevance to the story (and from here there developed the modern stage and cinematic musical). Offenbach became a master and leading composer of operetta, and most of his works may be described as such. Indeed, the musicologist R. Orledge notes that Offenbach invented the term for his 1856 show La rose de Saint-Flour (Arnold, 1288).

Offenbach's theatre might have been tiny, and his performance license only permitted a cast of two or three characters per show, but the performances were very well-received by the multitude of Parisians who crammed themselves in up to the rafters. One witty journalist noted: "It is the David of opera houses and, in an indirect way, scatters worse wounds among the Goliaths, its big rivals, than they would care to acknowledge" (Schonberg, 357). Such was the financial success, Offenbach was able to permanently take over another theatre, the Théâtre Comte.

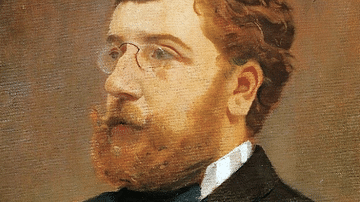

Offenbach's first full opera was Orphée aux enfers (Orpheus in the Underworld). It premiered in October 1858 and was a raging success, running for 228 consecutive performances. The original work had two acts, but Offenbach revised and extended it to four acts in 1874. Orpheus and his subsequent comic operas lampooned the traditional genre of operas, which told tales from Greek mythology. Offenbach made particular fun of the traditional rousing endings of French operas by adding, for example, a waltz. The composer never missed an opportunity either to take a satirical swipe at Parisian society. Offenbach not only staged his own works but also those of young up-and-coming composers, notably Georges Bizet's (1838-1875) Le Docteur Miracle.

Offenbach eventually wrote around 100 works for the stage, although at least half of these had only a single act. His most frequent librettists were Ludovic Halévy (who later co-wrote the libretto for Bizet's Carmen) and Henri Meilhac (1830-1897), while his chief soprano was Hortense Schneider, one of the singing superstars of the day. Offenbach's "witty, light-hearted operettas satirized composers such as Wagner and Meyerbeer and captured the prevailing hedonistic spirit of the Second Empire Paris, with its passion for music-hall dances and its relentless debunking of the Establishment" (Wade-Matthews, 393). La vie parisienne was a typical work with its famous can-can dance (aka galop infernal) finale. Orledge summarises Offnebach's particular slant at comedy as follows:

His musical parody consisted largely of quoting familiar themes in incongruous surroundings and the farcical element often lay more in the situations and texts he set, though he possessed an ability to heighten comic situations, to exploit rhythm and the stresses of the French language, and to build up excitement in his sparkling finales.

(Arnold, 1288)

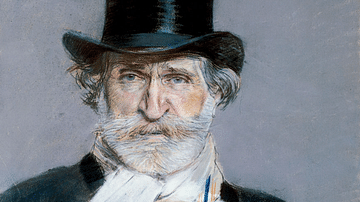

The Italian composer of comic operas Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) once described Offenbach as "the Mozart of the Champs-Elysées" (Wade-Matthews, 393). In a century beset with wars and revolutions, the historian S. Sadie notes that "the operettas and waltzes of Offenbach and Johann Strauss the Younger probably contributed more than anything else to the serious business of deliberately not being serious about the second half of the nineteenth century" (326). Offenbach was at the height of his fame in the 1860s. Big names like the English novelist William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-1863), the Russian author Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910), and even Emperor Napoleon III (r. 1852-1870) attended his operettas. Offenbach's reputation became international following commissions for performances in Vienna and in Bad-Ems in Germany. London and the United States soon staged Offenbach's works, too. Offenbach could afford to live in a grand residence in Paris and buy a large holiday home on the coast at the fashionable resort of Étretat in Normandy.

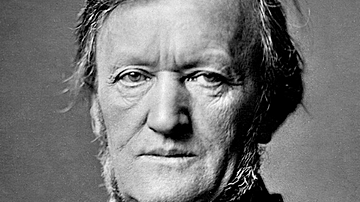

There were some critics of Offenbach and the ultra-comedic direction he had almost single-handedly swerved opera into. The German composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883) denounced Offenbach's work as "a dung heap on which all the swine of Europe wallowed" (Schoberg, 358). Neither did more prudish cultures appreciate the air of risqué innuendo and sheer naughtiness that seemed to cling to all of Offenbach's operettas. The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin felt that the composer's "pruriency is inexcusable" and that "he is the purveyor of bald, bad indecency" (ibid). This type of review only made people more curious to see what all the fuss was about.

Tales of Hoffmann

Offenbach's comedies continued to be wildly successful despite the snobbery and even antisemitism of several noted critics. In 1873, the composer had three productions all running simultaneously in Paris: Fantasia, La Boule de neige, and Le Corsaire noir. This was the peak, though, and from 1874, Offenbach's operettas fell out of fashion as the 1870s progressed; their comfortable predictability had become just a bit too predictable, and audiences tired of the social satire. As a consequence, Offenbach endured a run of flops that ruined him financially. The composer was obliged to find other means to raise funds, and so he toured the United States in 1876. The 30-night tour was lucrative, earning the composer an impressive $1,000 per performance. Still, when he returned to his beloved Paris, the composer was happy to state that "I am Offenbach again" (Schonberg, 362).

Offenbach noted that a different type of opera had gripped the public's imagination, operas like Die Fledermaus (The Bat) by Johann Strauss II (1825-1899), which was first staged in 1874. Ironically, it was Offenbach who had persuaded Strauss to write operas besides his famous waltzes. Now the master learnt from the student and completely changed his approach to stage music.

Offenbach's turn to more serious drama and return to his German roots resulted in Les contes d'Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann) of 1881, oddly enough, the work he is most famous for today. In a work he actually started in 1877, Offenbach went from the extreme of one-act comedies to a massive, five-act serious opera (or three acts plus a prologue and epilogue). Les contes d'Hoffmann's bulky libretto is mostly based on three tales written by the German Romantic Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (1776-1822). The three stories are The Sandman, The New Year's Eve Adventure, and Councillor Crespel.

The work was more or less finished, but because Offenbach died during rehearsals, it was made ready by Ernest Guiraud in 1881, who notably cut the Giulietta act. The premiere came in Paris on 10 February 1881 at the Opéra-Comique. An instant success, the opera was also staged in New York (October 1882) and London (April 1907). The Giulietta act was reinstalled for later performances. The correct sequence, as Offenbach envisioned it, should be:

Prologue

This takes place in the cellar of a wine seller in Nuremberg, Germany. Andrès receives a letter from Stella but is persuaded to give up this note to Councillor Lindorf, who then arranges a rendezvous between Stella and the poet Hoffmann. Hoffmann proceeds to recount the stories of three love affairs, one tale for each of the next three acts.

Act 1

This is the story of Hoffmann and Olympia, who is a speaking doll invented by Dr Coppelius (the same performer as Councillor Lindorf) and Spalanzani. By wearing magic spectacles (made by Coppelius), Hoffmann sees Olympia as a real person. The pair dance at Olympia's coming-out party and fall in love, but disaster strikes when, in revenge for being swindled by Spalanzani, Coppelius smashes Olympia.

Act 2

Hoffmann is now in Munich, where he falls in love with Antonia, the daughter of Councillor Crespel and a young singer frail with ill health. Dr Miracle (Councillor Lindorf in disguise again) uses the ruse of bringing a picture of Antonia's late mother to life in order to persuade her to sing once again. Antonia's singing results in her death, and Hoffmann loses his second love.

Act 3

Finding himself in Venice, Hoffmann falls in love for a third time, his heart's desire being Giulietta, a courtesan. Giulietta is under the control of the sinister magician Dapertutto (Lindorf once again). Dapertutto wants nothing less than Hoffmann's soul, and so Giulietta is forced to entrap him. Hoffmann kills Schlemil in a duel so that he can possess the key that will unlock the chamber Giulietta has been imprisoned in. Hoffmann is too late, though, and Giulietta is spied leaving on a gondola in the company of a dwarf called Pitichinaccio. For the third time, Hoffmann loses in love.

Epilogue

We return to the wine seller's tavern in Nuremberg, where Hoffmann is too drunk to notice the arrival of Stella, who is taken away by Councillor Lindorf, his nemesis and seemingly the effortless controller of Hoffmann's fate.

The "Barcarolle" – originally a genre of boating song with a distinctive 6/8 rhythm – from the Entr'acte of the opera is perhaps the single most recognisable piece of music by Offenbach, although he had first written the tune for his three-act opera Die Rheinnixen back in 1864.

Major Works

The most important operatic works by Jacques Offenbach include:

Orphée aux enfers – Orpheus in the Underworld (1858)

Geneviève de Brabant (1859)

La belle Hélène – The Beautiful Helen (1864)

Die Rheinnixen – The Rhine Nixies (1864)

Barbe-bleue – Bluebeard (1866)

La vie parisienne (1866)

La grande duchesse de Gérolstein – The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein (1867)

La Périchole (1868)

Les contes d'Hoffmann – The Tales of Hoffmann (1881)

Death & Legacy

Offenbach died in Paris on 5 October 1880. His funeral service was held in La Madeleine church in Paris, the coffin was taken on a tour of the theatres of the city and then interred in the cemetery of Montmartre. In one obituary, the noted critic Eduard Hanslick summarised Offenbach's unique contribution to the theatre:

Much as he wrote, Offenbach was always original. We recognise his music as Offenbach-ish after only two or three bars, and this fact alone raises him high above his French and German imitators, whose buffo operas would shrivel up miserably were we to confiscate all that is Offenbach-ish in them. He created a new style in which he reigned absolutely alone.

(Schonberg, 362)

Offenbach's approach to comic opera influenced other composers, notably in France where he led a sort of school of operetta composers that included Hervé (1825-1892), Charles Lecoq (1832-1918), Robert Planquette (1848-1903), and André Messager (1853-1929). Offenbach was also influential in England. Many of Offenbach's operettas were successfully staged in London and "the element of the theatre of the absurd that Offenbach invented in his operettas…did find its way into the Savoy operas of Gilbert and Sullivan" (Sadie, 326). One might also reasonably claim that it was Offenbach more than any other composer who, with his operettas, provided the crucial link between the comic opera which preceded him and the modern musical which followed in the 20th century.