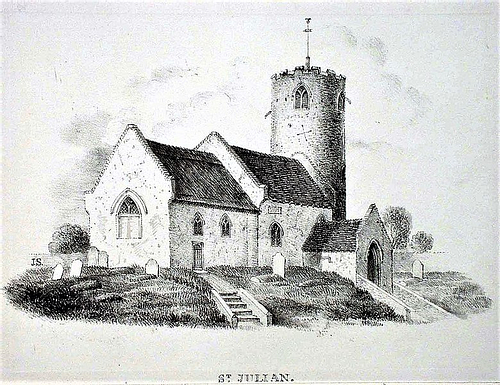

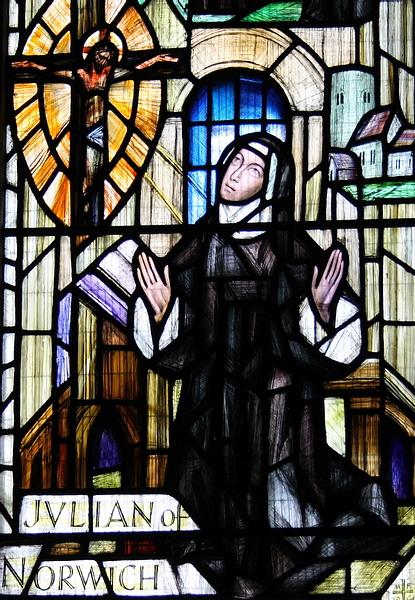

Julian of Norwich (l. 1342-1416 CE, also known as Dame Julian, Lady Juliana of Norwich) was a Christian mystic and anchoress best known for her work Revelations of Divine Love (Julian's original title: Showings). Almost nothing is known of her life since, as an anchoress (a woman who lives in seclusion, dedicated wholly to God), she would have been disinclined to discuss details of whatever previous life she led in the world. Even her actual name is unknown as “Julian of Norwich” derives from her residency at St. Julian's Church in Norwich, England.

According to her book, when Julian was 30 and a half years old, she was struck with an illness so severe she knew she would not survive. The parish curate administered last rites, and she began to experience visions from God. These visions lasted throughout the afternoon of 13 May 1373 CE (15 of them) and a final vision the next evening (for a total of 16), when she woke completely cured and, shortly afterwards, wrote them down.

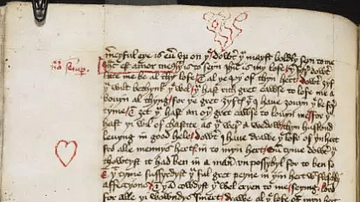

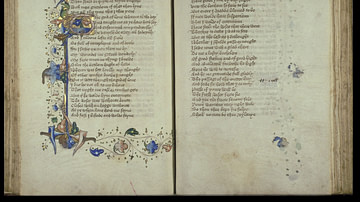

This early version of her visions is known today as the Short Text. At some point in the 1390's CE, Julian returned to the work and expanded it to create the manuscript now known as the Long Text. Neither version seems to have been known during her lifetime, but she was much sought after for spiritual counsel and became famous for her wisdom and piety. The Christian mystic Margery Kempe (l. c. 1373 - c. 1438 CE) visited her for counsel in c. 1413 CE and, along with bequests left to her in wills, substantiates Julian's historicity.

Biographical Information

Her book of brilliant, mystical revelations has intrigued and inspired reading audiences since they were first published by the Benedictine monk Serenus de Cressy (l. c. 1605-1674 CE) under the title Sixteen Revelations on the Love of God in 1670 CE. The beauty of the work and the complete lack of biographical information on the author has encouraged later writers and scholars to construct their own biographies for her based on 'clues' they seize upon in the book which are then linked to knowledge of life in the Middle Ages.

These life stories variously depict Julian as a widow who lost her family to the plague and renounced the world, a scholar who turned her back on society, and a layperson who only became an anchoress after her visions, among other possibilities. In reality, nothing can be claimed about Julian's life since all that is known is what she mentions in her work, and from that one learns that she lived in Norwich as an anchoress, experienced a near-fatal illness, had a mother who tended her while sick, and was served by a maid.

Her historicity is established through bequests left her in wills between 1394-1416 CE. One of these bequests mentions a maid named Sarah who served her and an earlier maid named Alice. She is also mentioned, in glowing terms, by the mystic Margery Kempe in her autobiography (the first in English), The Book of Margery Kempe. Kempe experienced visions and voices which she believed came from God but was routinely mocked and doubted. She therefore went to Norwich where her visions told her to seek out Julian for validation. Her account reads:

And then [I] was commanded by our Lord to go to an anchoress in the same city who was called Dame Julian…for the anchoress was expert in such things and could give good advice. (Chapter 18)

Kempe's description of Julian's answers to her questions is completely in keeping with Julian's own visions in her work. This detail validates the historicity of the author in that Kempe never mentions Julian's book anywhere in her autobiography even though she never misses a chance to tell a reader of any spiritual work she has heard of. At one point, Julian says to Margery:

The Holy Ghost never urges a thing against charity, and if he did, he would be contrary to his own self, for he is all charity. (Kempe, ch. 18)

This sentiment could as easily be interpreted as coming from scripture, but Margery further relates Julian referencing Saint Paul and Saint Jerome and linking them back to her emphasis on the transcendence and immanence of Divine Love, which echoes Julian's visions.

Life as an Anchoress

Further support for Julian's historicity is that the bequests, and details mentioned in her work, are consistent with the life of an anchoress in the Middle Ages. The treatise Ancren Riwle (“Anchorite Rule”, a guidebook for the anchorite/anchoress written c. 1127-1135 CE) stipulated how an anchorite or anchoress should behave, how they should be enclosed after taking their vow, and how they should be tended by whatever institution they were attached to. Scholar Margaret Deanesly comments:

Before either hermit, anchor or anchoresses established themselves, they had to seek permission from the bishop, show that they had sufficient endowment, or some prospect of maintenance, and were suitable in character. Anchorites and anchoresses must have sufficient [funds] to support one or two servants, as they could not fetch food for themselves. Many had cells in towns, where alms would be bestowed on them…Their primary work was prayer, though they might give spiritual counsel to those that sought it. An anchorage generally consisted of two or three rooms beside the chancel of a church. (211)

One interesting aspect of Julian's life, as evidenced by Margery Kempe, is that she seems to have been allowed to speak to people face-to-face instead of through a small window in the wall (similar to that in a Catholic confessional booth). She most likely came from a family of means who were able to support her at the anchorage for most of her life since bequests for her support do not appear until later, after 1394 CE (though one must consider the possibility that earlier bequests have been lost). The fact that her mother was present during her illness also suggests she came from an upper-class family of wealth since such families were always allowed special privileges denied the lower class, and it is a certainty that no anchoress of modest means would have been allowed family visitations.

Once an anchoress had entered her cell, she was considered dead to the world. Scholars Frances and Joseph Gies describe the ritual which began their service and how they then spent their lives:

Women committed themselves to living out their lives as anchoresses enclosed in cells attached to churches, monasteries, convents, sometimes even castles. The anchoresses were consigned to their cells with the saying of a mass – usually, as with lepers shut up in their colonies, that of the Dead; holy water was sprinkled in the cell, the recluse prostrated herself on a bier, earth was scattered over her, and the officiating priest left the cell with the instructions, “Let them block up the entrance to the house.” The cells were usually composed of more than one room, and often two or more anchoresses lived in adjacent cells, with servants to provide them with food and other necessities. The recluses' time was spent in prayer, and sometimes in work such as embroidery; often they were consulted as wise women and spiritual advisers. (92)

All of this is consistent with Julian's life as revealed in her book and that of Margery Kempe. It is possible, even likely, that Julian took religious orders at a young age since many aristocratic young women chose that life over the intrigues of court, domination in marriage, and the prospect of dying young in childbirth. Another famous Christian mystic of the Middle Ages, Hildegard of Bingen (l. 1098-1179 CE), was enrolled in a convent by her family at the age of seven and quite happily spent the rest of her life removed from the common lot.

Julian's Illness & Visions

Whoever she was, and whatever her background, she had a near-death experience at the age of 30, which would lead her to write the book that has made her famous. Julian writes:

And when I was thirty and a half years old, God sent me a bodily sickness in which I lay for three days and three nights; and on the fourth night I received all the rites of Holy Church, and did not expect to live until day. But after this I suffered on for two days and two nights, and on the third night I often thought that I was on the point of death; and those who were around me also thought this. But in this I was very sorrowful and reluctant to die, not that there was anything on earth that it pleased me to live for, or anything of which I was afraid, for I trusted in God. But it was because I wanted to go on living to love God better and longer and, living so, obtain grace to know and love God more as he is in the bliss of heaven. For it seemed to me that all the time that I had lived here was very little and short in comparison with the bliss which is everlasting. (Short Text, ch. II; Long Text, ch. III)

In her opening chapter, Julian says how she prayed for this kind of illness since she was a young girl after hearing the story of Saint Cecilia who received three wounds to her neck from a sword, died, and was translated to heaven. Julian says that afterwards she prayed for three graces from God:

- To have a recollection of Christ's Passion

- To have a bodily sickness so severe that it should appear mortal

- To have three wounds from God: Contrition, Compassion, and Longing for God

The recollection of Christ's Passion and the three wounds, she says, would arise from the sickness which would draw her closer to an understanding and love of God. She writes:

In this sickness, I wanted to have every kind of pain, bodily and spiritual, which I should have if I were dying, every fear and assault from devils, and every other kind of pain except the departure of the spirit, for I hoped that this would be profitable to me when I should die, because I desired soon to be with my God. (Short Text, ch. I; Long Text, ch. II)

After recovering from her illness, Julian wrote the Short Text which she later expanded. The Short Text is the unadorned account of what she saw and what she thought the visions meant without further elaboration. Julian was a daughter of the Church in the Middle Ages when it was understood that the Church's word and God's were synonymous. Many of the visions seemed to contradict and criticize the actions of the medieval clergy, if not Church teaching itself (especially in regard to women), but it would take Julian years of prayer and meditation to reconcile her faith-as-learned with her faith-as-experienced in the visions. Julian scholars Edmund Colledge and James Walsh comment:

In 1388, if not later, she at last understood for the first time the totality of the revelations, and what is now found in the long text, but is unrepresented in the short text and in the long text's introductory summarizing chapter, shows us which mysteries in the revelations were unlocked for her and described by her only after final enlightenment. (26)

Among these mysteries is Julian's famous understanding that, in spite of appearances to the contrary, God assures humanity that all will be well in the end. God is eternal love, Julian understands, and can only offer of Himself what He is; in God, therefore, there is no condemnation, only acceptance.

Necessary Sin & Mother Jesus

Julian receives this message in her 13th revelation, recorded fully in Chapter 27 of the Long Text. She understands that “all would have been well” in life, for everyone, if there had been no sin but, because there was, Jesus had to suffer and die and people every day suffered and died. She recognizes that this is a dangerous line of thought because she is questioning the will of God and says how she knows “the impulse to think this was greatly to be shunned” but she cannot help herself and grieves over the suffering of humanity caused by sin and death.

Jesus comforts her, though, telling her that sin is necessary but that “all will be well, and all will be well, and every kind of thing will be well.” She understands then the nature of sin as transitory and having “no kind of substance, no share in being, nor can it be recognized except by the pain caused by it” and further recognizes that what one calls 'sin' is an important aspect of life in the flesh in that it “makes us know ourselves and ask for mercy.” She internalizes Jesus' words and concludes with the comforting thought that, because of God's love freely given to all, “it is true that sin is the cause of all this pain but all will be well and every kind of thing will be well.”

She consistently depicts Jesus as a kind and loving guide who explains and listens patiently without judgement. Julian's Jesus is consistent with the figure from the biblical gospels but not so much with the Christ figure of the Middle Ages who was routinely cited by clerics as inspiring and justifying various slaughters and other injustices. Like Hildegard of Bingen, Julian recognizes in the Divine a feminine aspect – just as vital as the male – a nurturing force, immanent in nature, which draws souls close to it, comforts, and elevates.

In the 60th chapter of the Long Text, Julian discusses the penetration of the Divine into human consciousness. She writes:

I understand three ways of contemplating motherhood in God. The first is the foundation of our nature's creation; the second is his taking of our nature, where the motherhood of grace begins; the third is the motherhood of work. And in that, by the same grace, everything is penetrated in length and breadth, in height and in depth without end; and it is all one love. (Long Text, ch. 60)

The motherhood of creation is clear in that God gives birth to all things; the motherhood of nature is God taking human form in Christ; the motherhood of work is God's ongoing relationship with humanity through which he draws people to a higher purpose. Julian depicts God as the All-Mother nurturing her children:

The mother's service is nearest, readiest, and surest: nearest because it is most natural, readiest because it is most loving, and surest because it is truest. No one ever might or could perform this office fully except only him. We know that all our mothers bear us for pain and for death. O, what is that? But our true Mother Jesus, he alone bears us for joy and for endless life, blessed may he be. So he carries us within him in love and travail, until the full time when he wanted to suffer the sharpest thorns and cruel pains that ever were or will be, and at the last he died…And he revealed this in these great surpassing words of love: If I could suffer more, I would suffer more. (Long Text, Ch. 60)

Julian's Jesus is mother, friend, confidante, protector, and savior, always present but never intrusive, available for advice and guidance but never judgmental or bullying. Her visions showed her a transcendent God who was also close as a mother's love and gentle as the best of friends.

Conclusion

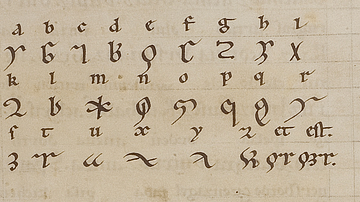

Even if her work had been popularized in her lifetime, it would have been ignored by the medieval Church who needed a far more robust and angry Jesus, bristling with righteous, masculine rage, for its purposes. Her Showings had to have been known at least in her community, though, because the Short Text survives in a copy while the Long Text in more than one, the work of female scribes who ensured the preservation of her visions. Her work is never mentioned by any medieval writers, however, and if it were not for Serenus de Cressy's publication of it in the 17th century CE, Julian's name might never have been known and the work of one of the greatest mystics of all time lost.

Even though throughout Revelations of Divine Love, Julian refers to herself as 'unlettered', this is a simple rhetorical device commonly used by writers of the time asking for a reader's indulgence should there be any offense (Colledge & Walsh, 19). She wrote well and was clearly well-read as her work shows an acquaintance with the Bible, the writings of the Church Fathers (such as St. Jerome), Augustinian philosophy, and Boethius' famous Consolation of Philosophy, which she would probably have read in the translation by Geoffrey Chaucer (l. c. 1343-1400 CE), her contemporary.

Her work was republished in 1901 CE in a complete version modernized and introduced by Grace Warrack, who took it upon herself to painstakingly copy Julian's book by hand. Warrack's work found an admiring audience in the writers and thinkers of the time. The poet T. S. Eliot in his Four Quartets (1941 CE) popularized the line, “All will be well and every manner of thing will be well,” and other artists have drawn inspiration from Julian before and since Eliot's work. Julian has been praised by demographics as diverse as the modern-day Church and so-called New Age and Wiccan adherents as her voice is timeless and her concept of a divine and all-encompassing love resonates above doctrinal differences, dogmas, or artificial divisions in articulating a vision of God in which everyone is welcome.