Margery Kempe (l. c. 1373 - c. 1438 CE) was a medieval mystic and author of the first autobiography in English, The Book of Margery Kempe, which relates her spiritual journey from wife and mother in Bishop's Lynn, England to a chaste Christian visionary and popular – if controversial – public speaker. Kempe was illiterate and dictated her life story first to her son and then to a priest, as she records in her book, and it remains a significant resource on Christian spirituality and life in the Middle Ages.

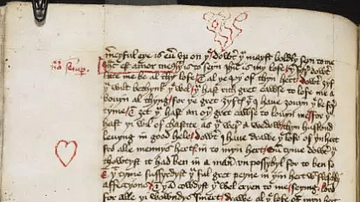

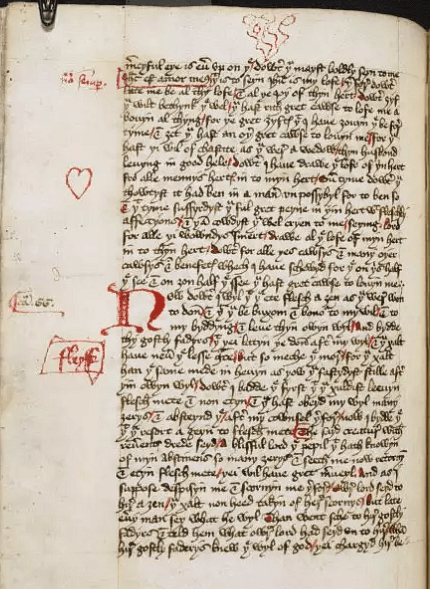

The final version of the book was completed in July 1436 CE and must have enjoyed some level of popularity because excerpts were printed in 1501 CE by Wynkyn de Worde (d. 1534 CE) who worked in England with the printer William Caxton (c. 1422 - c. 1491 CE), publisher of the works of Geoffrey Chaucer (l. c. 1343-1400 CE) and Sir Thomas Malory (l. c. 1415-1471 CE). The book itself was lost for centuries until the manuscript was found in a cupboard of the home of Lt.-Col. William Erdeswick Ignatius Butler-Bowden (1880-1956 CE) of Southgate House, Chesterfield, England and authenticated by the American scholar Hope Emily Allen (1883-1960 CE).

In the present day, it is considered a classic of medieval literature but is also considered significant in depicting the life of a woman in the Middle Ages, the lucrative pilgrimage business and travel, and the powerful role religion played in the lives of the people. The book is most memorable, however, for the honesty of the author's voice as she relates the story of her relationship with God and her adventures and near-fatalities among those who professed to believe in that same God but did not believe in her.

Early Life & Conversion

Almost all that is known of Margery Kempe comes from her book. Town records of Bishop's Lynn (now known as King's Lynn, Norfolk, England) record her father, John Brunham, as mayor of the town five times between 1370-1391 CE and a member of parliament, justice of the peace, and chamberlain. Kempe references her father with pride, often at the expense of her husband, John Kempe, whom she married at the age of 20 c. 1393 CE.

As she reports, she was proud of her upper-class family and fond of fine clothes and high fashion and would dress to impress her neighbors. Throughout her book, Kempe refers to herself in the third person as “the creature” or “this creature” to emphasize her humility. In Chapter Two she writes:

She was enormously envious of her neighbors if they were dressed as well as she was. Her whole desire was to be respected by people. She would not learn from a single chastening experience nor be content with the worldly goods that God had sent her – as her husband was – but always craved more and more.

After her first child was born later in 1393 CE, Kempe suffered a psychological crisis which, today, would most likely be recognized as postpartum depression. She experienced vivid hallucinations and visions of hell, biting and scratching herself until she was finally restrained by her husband and the house servants, tied to her bed.

These visions tormented her continually until one day when she woke alone in the room to find Jesus Christ sitting beside her. He asked, “Daughter, why have you forsaken me, and I never forsook you?” and then ascended slowly and vanished (Chapter One). Instantly, Kempe's mind was clear and she regained her senses, asked to be released, and resumed her former life.

Failing to understand what Jesus meant by “forsaking him”, Kempe not only continued her devotion to worldly pleasure, she increased it by opening up a brewery “out of pure covetousness” (Chapter One). The business failed, however, because Kempe had no idea how to operate a brewery and her servants, who seem to have been fine brewers, could not make the business work. When the brewery failed, she then opened a mill but the horses would not work, and this failed as well. These failures were interpreted by her neighbors as God punishing her and no one would work for her further. Only at this point did Kempe understand that she had to change and devote her life to something outside of herself and her own selfish interests.

She did penance for her sins, attending church services and going to confession two or three times a day. She records how, one night, she heard sweet music playing, more beautiful than any she had ever heard, and knew it came from paradise. The melody was so lovely, she began to cry and, afterwards, when she heard any music, was touched by sympathy for others or was moved by her devotion to God, she would fall into fits of loud, uncontrollable sobbing.

Kempe's weeping would come to define her afterwards and, along with her newfound piety and tendency to tell her friends and neighbors about the joys of heaven and love of God, annoyed those around her who were used to the old Margery Kempe and her vanity and worldly values. She also came into conflict with her husband after telling him she no longer wanted to have sex with him as she was now devoted to God. She understood, however, that it was her duty as his wife to sleep with him but stipulated that he could have her body but that her soul had been given to Jesus.

Post-Conversion & Early Travels

When Kempe was 40 years old, married 20 years and having borne her husband 14 children, she made a bargain with her husband to allow her to live a chaste life. Kempe agreed to pay off her husband's debts and to give up her Friday fasts and eat and drink with him as she used to and, in return, he agreed to renounce any claims to her body and allow her to travel wherever God should lead her.

One of the first places she went, with her husband in tow, was Canterbury where she was almost burned at the stake for being a Lollard. The Lollards were a pre-protestant sect, initiated and inspired by the scholar John Wycliffe (l. c. 1320-1384 CE), advocating church reform – especially reform of the clergy – and a translation of the Bible into the vernacular. By the time Kempe came to Canterbury, the term “lollard” was synonymous with “heretic”. Kempe answered her accusers quoting scripture but was still in danger until she was rescued by two handsome men whom she suggests were angels and who guided her back to her inn unharmed (Chapter Thirteen).

Although she was illiterate, she had a fine memory and retained all that was taught to her. In Chapter Fourteen she says how she learned the Bible and other religious works by “conversing about scripture, which she learned in sermons and by talking with clerks.” She knew the Bible as well as the works of the English mystics Walter Hilton (l. c. 1340-1396 CE) whose Scale of Perfection had become almost required reading for religious orders (written especially for anchoresses) and Richard Rolle (l. c. 1300-1349 CE) and his highly influential Fire of Love, an account of his mystical experiences.

Probably her greatest influence, however, was the work and example of the mystic Saint Bridget of Sweden (l. 1303-1373 CE) whose Revelations Kempe had someone read to her and then internalized. Bridget was both mystic and prophet who began receiving visions from God at the age of ten and, after she became widowed, devoted her life to the service of others, particularly unwed mothers and their children. She encouraged complete devotion to God and the Church as the ultimate reality and supported the medieval Church's teachings fully even though those very teachings prohibited women from speaking or teaching in the presence of men.

Kempe's visions are similar to Bridget's in their depiction of Christ as husband, lover, close friend, and confidante as well as transcendent Lord and Savior. Bridget, an aristocratic widow with vast resources, was able to write and speak of her visions without rebuke from the Church and do as she pleased without condemnation from others; Kempe was in no such position as the wife of a merchant of modest means. When Bridget spoke, people listened; when Kempe spoke, people mocked.

Kempe's visions continued and Christ commanded that, henceforth, she should wear only white as a show of her purity and rebirth. White clothing for women was reserved for nuns in an order, however, and when she began wearing white later on, this caused her even more problems. She already had more than enough at this time as many people, especially male clerics, rebuked her, reminding her of Saint Paul's prohibition against women speaking in public or attempting to teach men. Even so, as she writes, her fame had spread and, on her way to London from Canterbury, “many worthy men wanted to hear her converse, for her conversation was so much to do with the love of God” and she appears at this time to have become a popular public speaker (Chapter 16).

Still, she began to doubt herself and her visions and so went to visit the mystic anchoress Julian of Norwich (l. 1342-1416 CE). Julian comforted and assured Kempe that her visions and her weeping for the sins of the world came from God, not her own mind or the Devil, and that she should continue as she had been doing. Scholar Barry Windeatt comments on the meeting specifically and what this says about Kempe's memory and memoir overall:

The accuracy of Margery's memory, where this can be cross-checked with recorded events, is impressively good, while her recollection of what was said to her at their meeting by Dame Julian of Norwich is also impressive with a different kind of accuracy in that what Margery records Julian as saying rings true in content, and even in style, with Julian's own writing. Since it seems unlikely that Margery would know anything of Julian's written work, her memory of this conversation is at once a precious witness to the wholeness of vision, life, and counsel in Dame Julian, and a witness to the quality of Margery's own power to recollect what was said to her both on this and, by implication, on other occasions. (26)

Having been assured by Julian, Kempe continued on her way and, after paying off her husband's debts as promised, she left on pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1413 CE in fulfillment of an earlier command from God.

Pilgrimage & the Book

Kempe's description of her travels is far from any recognizable travel writing of any time. As Windeatt notes, “Margery would probably not have believed that human experience was worth recording for its own sake” (22). Although she traveled to Jerusalem, Rome, Assisi, Norway, Germany, and went on pilgrimage through Spain to Santiago de Compostela, she notes little of the day-to-day details and instead focuses on her visions and how other people treated her.

In Rome, for example, she relates how she could not stop weeping for the suffering of others and how God sent her warnings about impending storms to keep her safe but little about the place itself (Chapter 39). On a later voyage, she begins to describe a storm at sea and how she had no money but again shifts focus to the power of prayer and how God swiftly sent them good weather to reach their destination and provided for her financially (Chapter 43). When a man of Norwich consents to have white clothes made for her, she begins to talk of her pilgrimage to Santiago in 1417 CE but then shifts to the criticism and cruelty she endured from others for wearing white, weeping, and for her talk of God (Chapter 44). At the same time, Kempe does provide details on the pilgrimage business in the Middle Ages and the various agencies at ports and along the routes who made considerable fortunes from it.

Throughout her travels, Kempe was repeatedly charged with heresy and, in 1417 CE, was detained at Leicester on her way back from Spain and put on trial. She was again cleared of heresy and, as usual, released with a warning to stop behaving as she did; a warning she consistently ignored. She returned home to care for her ailing husband who died in c. 1431 CE. It seems to have been about this same time that her son, also known as John Kempe, returned from where he was living in Germany and took dictation as Kempe told him of her experiences; thus creating the first draft of her book.

John-the-younger also died that same year, and Kempe and her daughter-in-law traveled to Norway and then back to Germany. When Kempe returned home c. 1436 CE, she found the work her son had done on the book incomprehensible and had a priest, most likely her long-time confessor and confidante, revise and add to the work. The Book of Margery Kempe, as it would later be called, was fully revised in 1438 CE, the same year Kempe is assumed to have died as she receives no further mention in town records after her admission to the Guild of the Trinity that April.

Discovery

The manuscript must have circulated for some time and gained some attention for excerpts from it, credited to her name, were chosen by Wynkyn de Worde for inclusion in a book of pious sayings in 1501 CE. These excerpts were all that was known of Margery Kempe until 1934 CE when her complete manuscript was found in the cupboard of the Butler-Bowden home. The family was playing ping-pong in the living room in the company of a friend who was visiting and one of them stepped on the ball. The extra balls and bats were kept in a cupboard in the living room and Lt.-Col Butler-Bowden went to fetch a new one but had a hard time finding it because of the mess of old manuscripts which were also housed there.

The visiting friend, one Charles Gibbs-Smith of the Victoria and Albert Museum, went to help and noticed the manuscript. He asked if he could show it to a colleague, Mr. Albert Van de Put, and Butler-Bowden agreed. The manuscript was authenticated by the independent scholar Hope Emily Allen (“independent” as in not affiliated with any university or institution) in 1934 CE and she prepared the first modern version published in 1940 CE.

How the manuscript came to the Butler-Bowden home is unknown, but Lt. Col Butler-Bowden offered this explanation:

It may be remembered that we are a Catholic family and I believe that, when the monasteries were being destroyed, the monks sometimes gave valuable books, vestments, etc. to such families in the hope of preserving them. Though there is nothing to prove it, this may have been the case with Margery Kempe's manuscript and Carthusians of Mount Grace may have given it to one of my family. (Kelliher, 260)

The reference to the monasteries being destroyed is to the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII between 1536-1541 CE during England's Protestant Reformation. The allusion to the Carthusians of Mount Grace refers to a priory in Yorkshire whose name was inscribed inside the leather cover of the manuscript and one of whose monks, a John Awne (d. 1472 CE), is noted as the copyist. As late as 1472 CE, then, Kempe's book was considered worthy of copying and preserving and there were no doubt a number of other copies in circulation, which would have made it worth Wynkyn de Word's notice.

Conclusion

Margery Kempe's work continues to intrigue and fascinate readers in the modern day just as it must have shortly after her death. Scholars have debated whether the book can rightly be called an autobiography when it was actually written by someone else, whether it should instead be called a hagiography (saint's life), and other details of the work, but no one has ever questioned the authenticity and sincerity of the narrator's voice.

The Book of Margery Kempe still enjoys such popularity because of the honesty of the narration. Kempe never tries to present herself as anything other than she is, and as Windeatt notes above, her memory of actual events – for the most part – is so consistent with known facts that it seems unlikely she would alter others for her own benefit. Her visions of God's all-embracing love echo those of other female mystics of the Middle Ages such as Saint Catherine of Sienna (l. 1347-1380 CE) and Julian of Norwich, and her constant weeping and uncontrollable sobbing is reported by still others such as Angela de Foligno (l. c. 1249-1309 CE) and Dorothea of Montau (l. 1347-1394) as noted by Windeatt (20-21).

In fact, considering how popular the Cult of Saint Bridget was in England at Kempe's time, how well-known and widely read Saint Catherine's works were by English clergy, and how well-established it was that both these women wrote of Christ as their husband – just as Kempe claimed for herself – one cannot help but question why she was so consistently doubted, ridiculed, and forced to defend herself against heresy. The most likely answer is that few people who profess a belief really want to meet up with the object of their faith as that would most likely require them to dramatically change their way of living; just as it did with Margery Kempe.