The Carolingian Dynasty (751-887) was a family of Frankish nobles who ruled Francia and its successor kingdoms in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. The dynasty expanded from Francia as far as modern Italy, Spain, and Hungary, and ruled the eponymous Carolingian Empire (800-887), the largest European political entity to exist until the 19th century.

The Carolingian name is derived from the dynasty’s common usage of the name Charles and refers to Charles Martel (688-741), remembered today for his leadership in repelling the expansion of the Moors into Gaul, and to Charlemagne, King of the Franks (r. 768-814) and Holy Roman Emperor (r. 800-814). Charlemagne’s coronation in 800 as Emperor of the Romans established the foundation of the Holy Roman Empire, although this terminology is anachronistic and was not standardized until the 12th century.

The Carolingian kings and emperors dominated the politics of Central Europe in their time but faced constant challenges to their rule. Despite its powerful height, the Carolingian Dynasty succumbed to succession disputes, civil war, and territorial partitions in the mid-9th century. The partitions established the political basis for the Holy Roman Empire, as well as modern France, Germany, and Italy. The Carolingian Dynasty’s territorial expansion, policies, and relationship with the medieval church are often viewed as foundational in the development of modern Europe.

Rise of the Carolingians

The Carolingian Dynasty was formed from the union of the Pepinid and Arnulfing houses and grew to power during the 8th century in Francia as its political predecessor, the Merovingian Dynasty (458-751), collapsed. Descended from Clovis I, King of the Franks (r. 481-511/513), the Merovingian kingdom encompassed Burgundy, Gaul, Swabia, and western Switzerland, which included the region’s routes through the Alps into Lombardy. The Merovingian domains abided by partition inheritance laws, which decentralized the kingdoms and made them vulnerable to internal conflict. The resulting territorial wars among the Merovingians caused the loss of dynastic influence to the mayors of the palace, officials similar to a modern prime minister. The mayors, acting as de facto political administrators, oversaw all court business and partition arrangements. As Merovingian influence atrophied from unrest and war, the mayors came to rule as power brokers while the kings acted as ceremonial figureheads.

Members of Carolingian lineage held the title of mayor in Austrasia, the northeastern region of Francia at the current-day intersection of Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, from the end of the 7th century, but the family’s historical prominence was not achieved until the life of Charles Martel. Charles became the mayor of Austrasia (r. 714-741) after the death of his father, Pepin II of Herstal, and overcame the Merovingian period’s civil wars. By the end of 718, Charles united the various regions of Francia under his sole mayoral authority. After the death of the Merovingian king Theuderic IV in 737, Charles refused to install a new monarch and effectively ruled over Francia himself until his death.

Charles Martel expanded his influence further by subjugating Francia’s rebellious kingdoms, forcing neighboring entities into becoming tributary states, and supporting Christian missionary goals in the pagan east, particularly those of Saint Boniface. A Christian warlord, Charles garnered contemporary and historical renown for his successes against the Muslim expansion into Francia by the Umayyad Caliphate and specifically for his victory at the Battle of Tours in 732. In 739, Pope Gregory III (r. 731-741) petitioned Charles Martel for his intervention on the Italian peninsula to defend the papal lands from the Lombards. Charles Martel died in 741, but the papal-Carolingian relationship would be forged over time.

At Charles’ death, mayoral control of Francia was passed to his sons, Pepin the Short and Carloman, who abdicated in 747. To start their rule with stability, the brothers reestablished the Merovingian monarchy and made Childeric III (r. 743-751) their puppet king. In 751, Pepin the Short (also known as Pepin III or Pippin III) deposed Childeric and usurped the throne for himself. Pepin was subsequently crowned by Pope Zachary (r. 741-752) as the first Carolingian King of the Franks (r. 751-768), thereby officially removing the Merovingians from power and legitimizing the rule of the Carolingian Dynasty.

Pepin used his new role to expand the Frankish kingdom’s influence in Europe. In 754, he intervened in the Lombard invasion of papal territory at the behest of Pope Stephen II (r. 752-757). The Franks successfully defeated the Lombards and captured the province of Ravenna, which Pepin then granted to the pope. The Donation of Pepin, as this transaction became known, established the foundation of the Papal States and supported future papal claims to secular authority.

Charlemagne

While Pepin the Short was the first of the Carolingian kings, it was his son Charlemagne who brought the dynasty to historical immortality. Known for his military leadership, pagan intolerance, and aggressive expansionism, Charlemagne reigned as King of the Franks (r. 768-814) after the death of his father and as Holy Roman Emperor (r. 800-814) following his coronation by Pope Leo III (r. 795-816). From his capital at Aachen in Austrasia, he ruled alongside his brother Carloman I as co-king, but the siblings’ poor relationship kept them at odds until Carloman died in 771. Charlemagne then ruled alone as king with the support of the Frankish aristocracy and church.

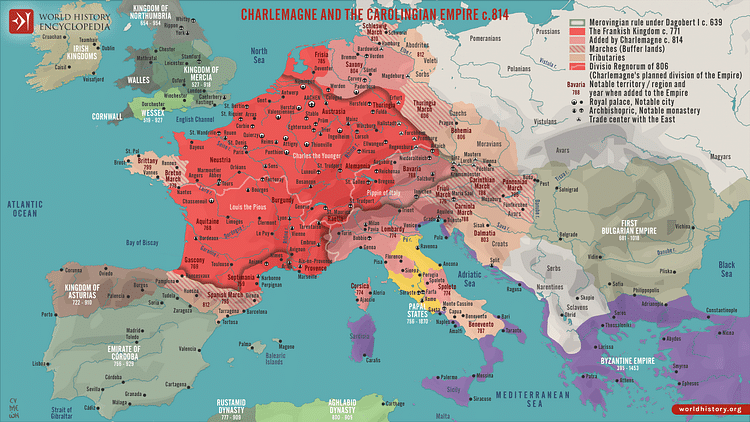

During his reign, Charlemagne developed the Frankish kingdom into a prosperous Western and Central European empire by expanding his influence on all territorial fronts by conquest. In 772, he initiated the Saxon Wars, a violent conquest of pagan Saxony which lasted until it was entirely under Carolingian jurisdiction in 804. Charlemagne continued Pepin’s papal alliance and came to the papacy’s defense in 773 against the Lombards. Victorious, he conquered the Lombard kingdom by 774, absorbed it into his burgeoning empire, and adopted the title King of the Franks and Lombards. By his death in 814, Charlamagne had doubled the size of the Frankish kingdom, expanding it to its territorial height through conquest westward to Barcelona, Catalonia, and Brittany, south through Italy to Rome, and eastward to Bavaria, Bohemia, Carinthia, Croatia, and Hungary.

Charlemagne concurrently and successfully conducted a kingdom-wide religious and moral reform program referred to as the Carolingian Renaissance. In addition to the Christianization of conquered populations, the Carolingian reforms included the standardization of church practices and canon, developments in education and literacy among the nobility, and the production of religious and intellectual texts.

Charlemagne arranged an alliance with Pope Leo III (r. 795-816), who sought protection from his local adversaries and foreign threats to church authority. On 25 December 800, the pope crowned Charlemagne as Roman Emperor. Although the coronation was the pope’s attempt at reviving the Roman Empire with papal oversight, the title was purely honorific and instead established the basis for a new Carolingian Empire (800-887) as well as its successors, the Holy Roman Empire. The immediate consequences, however, were more concrete: Charlemagne’s Roman title provided him with legitimate claims to the Lombard and Italian kingdoms.

Partition & Decline

Charlemagne’s last living son, Louis the Pious (Louis I; r. 813-840), inherited the Carolingian Empire at Charlemagne’s death in 814 after ruling a short time as co-emperor. Though he was not a warrior like his father, Louis engaged in conflicts with neighboring populations, including the Basques, Danes, and Vikings. He also continued many of Charlemagne’s reform programs and advocated for Christian unity within his kingdom but was particularly noted for his reorganization of the empire’s political structure. In his early years as emperor, Louis distributed the control of regional kingdoms within the empire to various kin, opting for the "imperial leadership of subordinate kingdoms, rather than a centralized, unitary state" (Wilson, 41).

In 817, Louis selected as heir and co-emperor his eldest son, Lothar I, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 840-855), and granted his other sons control over the subordinate regions. These territorial divisions and succession plans gave way to rivalries and factions among the Carolingians and other Frankish nobles. This decentralization of the Carolingian Empire gave increased authority to local governments and lords, thereby supporting the development of European feudalism and weakening the influence of the imperial throne. Like the preceding Merovingian rulers, the Carolingians gradually lost power due to the decentralization they fostered.

In 830, familial rivalries over Louis’s distribution of power and his plans for imperial succession sparked intermittent Carolingian civil wars over the next decade. After Louis the Pious died in 840, Lothar I claimed authority over the entire Carolingian Empire, bringing the conflict to its height. In 843, war was halted by the Treaty of Verdun, which partitioned the Carolingian realm into three domains - East Francia, Middle Francia, and West Francia - allocated to the sons of Louis the Pious. The imperial title was held solely by Lothar I, who claimed Middle Francia, the central portion of the empire which stretched from Italy in the south to Frisia in the north. East Francia went to Louis the German, while Charles the Bald, the youngest son, became king of West Francia. From this point, the Carolingian Dynasty faced a sharp decline as the three heirs and their descendants clashed with each other and with regional nobles over claims to greater power.

The kingship of Louis the German (r. 843-876) in East Francia was met with conflict in Saxony and on its eastern frontier. While the Rhineland regions of the kingdom were well established and home to the royal courts, the eastern reaches were largely decentralized and vulnerable to outside influences. In Saxony, Louis encountered the Stellinga uprising, a revolt by Saxon peasants who aligned themselves with Lothar I during the previous civil wars after Lothar promised to return the rights stripped from them by Charlemagne before their conversion from paganism to Christianity. Louis the German’s military quelled the Saxon revolt and eastern conflicts with the Bohemians and Moravians. Louis the German died in 876, and his territories were inherited by his three sons, Carloman of Bavaria (r. 876-879), Louis III the Younger of Saxony (r. 876-882), and Charles the Fat (r. 876-887).

After Lothar I died in 855, Middle Francia was partitioned further into the kingdoms of Lotharingia, Italy, and Provence by the Treaty of Prüm. Lothar’s son, Louis II of Italy, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 855-875) and King of Italy (r. 843-875), inherited the imperial title and ruled Italy with the wide aristocratic support, while Lotharingia was allotted to Lothar II (r. 855-869), and Provence went to the youngest son, Charles of Provence (r. 855-863). From Louis II’s inheritance in 855 until 924, the king of Italy typically held the imperial title.

During his reign as emperor, Louis II waged a lengthy assault on the Emirate of Bari in the Benevento region of southern Italy. It was successful, but the Beneventans rejected his rule in favor of the Byzantine Empire. After the Treaty of Mersen (Meerssen) in 870, the northern region of Middle Francia was fragmented further and transferred to the neighboring Frankish kingdoms, which left only the Burgundian and Italian domains to the Lotharingians. Louis II died without a legitimate heir in 875, resulting in the extinction of the Lotharingian line and a bout of succession conflicts over the transfer of Italy.

Charles the Bald, the youngest son of Louis the Pious, reigned as the king of West Francia (r. 843-877) and Italy (r. 875-877) and, following the death of his nephew Louis II, as emperor (r. 875-877). Of the three successors to Louis the Pious, Charles faced the most conflict. Throughout his reign, the Kingdom of West Francia was under constant threat by Danish Vikings and by another nephew, Pepin II, King of Aquitaine (r. 838-864), who inherited Aquitaine in 838. Pepin II refused to submit to Charles the Bald after the Treaty of Verdun granted him the entire western kingdom, which ushered in over two decades of intermittent warfare. Shortly after the death of Louis II in 875, Charles invaded Italy and usurped control from his nephew, Carloman of Bavaria. Charles the Bald died in 877, returning Italy to Carloman. In West Francia, he was succeeded by his sons, Louis the Stammerer (Louis II of West Francia; r. 877-879) and Carloman II of West Francia (r. 879-884). The imperial throne, however, went unfilled until 881.

Fall from Power

The deaths of Carolingian kings between 875 and 880 sent the dynasty into instability as regional nobles in each of the kingdoms attempted to seize power. With the Lotharingian and Western kings having died, the kingdoms were transferred to Louis the German’s last living son, Charles the Fat, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 881-887), King of East Francia (r. 876-887), Italy (r. 879-887), and West Francia (r. 884-887). From 876, Charles reigned as co-king of East Francia with his brother, Louis III the Younger, and as the sole king from the latter’s death in 882. He inherited Italy in 879 after the abdication of his eldest brother Carloman of Bavaria and, in 880, defended the Papal States against an invasion by Guy III of Spoleto (r. 872-882), a distant relative of the Carolingians. In exchange for his military intervention, Charles the Fat was crowned emperor by Pope John VIII (r. 872-882). Following the death of his nephew Carloman II of West Francia in 884, Charles the Fat was invited to assume the kingship of West Francia by the kingdom’s nobles.

Charles the Fat briefly reunited the Carolingian Empire after becoming the ruler of three main Carolingian kingdoms in 894, but his supremacy was challenged throughout the land. The empire collapsed for the final time when he was deposed in 887 by regional nobles after East Francia was usurped in a coup by his illegitimate nephew, Arnulf of Carinthia (r. 887-899). The Carolingian Dynasty has typically been considered to have ended with Charles's deposition. While the Carolingian line survived and some individuals maintained control in local duchies and counties, their power never reached the heights of their ancestors.

The Carolingian realm was split once more into separate territories: the kingdoms of East Francia, West Francia, Burgundy, and Italy. Nobles of the western kingdom elected Odo of West Francia (r. 888-898), an ancestor to the Capetian Dynasty of France, as their king, while Rudolf I of Burgundy was similarly elected the king of Burgundy. Arnulf retained East Francia and sought to revive the Carolingian Empire. In 894, he invaded Italy, which was contested by Guy III of Spoleto and Berengar I of Friuli (r. 888-924), a matrilineal grandson of Louis the Pious. Guy III’s strength made him Italy’s primary ruler over Berengar, and his proximity to the papacy influenced Pope Stephen V (r. 885-891) to crown him the first non-Carolingian emperor in 891. Arnulf successfully defeated Guy III in 896 and was crowned emperor, but he failed to consolidate his power and reinstate the empire before he died in 899.

East Francia was inherited by Arnulf’s son, Louis the Child (r. 899-911), but rule by regents and the uprising of local nobles made his reign ineffective. When Louis died heirless at age 17 or 18, the eastern royal Carolingian line also died. An election in the eastern kingdom passed control to the non-Carolingian Conrad I of Germany (r. 911-918), then to Henry the Fowler (r. 919-936), the Saxon patriarch of the Ottonian Dynasty (919-1024).

Italy was invaded after Arnulf’s death by Louis III, King of Provence (r. 887-928), a matrilineal grandson of Emperor Louis II. Successful in 900, Louis III was crowned King of Italy (r. 900-905) and Holy Roman Emperor (r. 901-905). Berengar repelled Louis III from Italy in 905 and blinded him in the process (from then, Louis the Blind). Berengar was later crowned Holy Roman Emperor (r. 915-924), but his death in 924 ushered in an imperial interregnum which ended in 962 with the coronation of Henry the Fowler’s son, Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 962-973).

Legacy

The Carolingian partitions of 843, 855, and 887 have all been viewed as the origin of modern European states. While the former partition has been interpreted as the end of Charlemagne’s great empire by its establishment of separate kingdoms, the latter division permanently separated West Francia, East Francia, and Italy, setting the three regions on unique paths of development. In West Francia, Frankish nobles continued to reign as kings after the collapse of the Carolingians, but the eastern kingdom transitioned to Saxon rule. This difference is usually considered the definitive split of the former Frankish empire into unique French and German political bodies. Similarly, the revival of the imperial title in 962 by Otto I, ethnically Saxon rather than Frankish, has also been interpreted as the birth of Germany. Italy, however, was contested for several centuries more by dukes, counts, and kings, though it remained within the Holy Roman Empire’s sphere of influence.