The Merovingian Dynasty was the ruling family of the Franks from roughly 481 when Clovis I ascended the throne of the Salian Franks until 751 when Childeric III was deposed and the Merovingians were supplanted by the Carolingian Dynasty as kings of Francia. The Merovingians established the largest and most powerful realm in western Europe, solidifying the Franks' dominance.

The name of the dynasty is derived from one of its forebears, Merovech, a semi-mythical Salian Frank leader who was said to have fought alongside the Romans at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields (451). Merovech's grandson, Clovis I (r. 481-511), was responsible for expanding Merovingian power into most of Gaul and parts of northern Germany, and for uniting all the Frankish tribes under a single rule. Upon Clovis' death, his kingdom was partitioned in equal parts among his four sons. Although the Merovingian kingdom was viewed as a single political entity, it became common practice that, upon succession, each Merovingian son would be given a piece of it to rule in his own name. This led to disunity within the Merovingian Dynasty and fostered civil war.

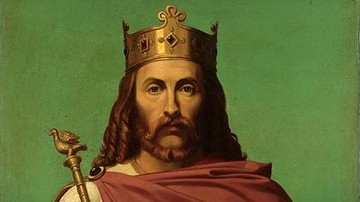

The Merovingians, often referred to as "long-haired kings", distinguished themselves from other Franks by keeping their hair long, and long hair soon became a symbol of their right to rule. A common way for Merovingians to dispose of rivals was to have them tonsured and sent off to a monastery since a Merovingian who cut his hair short was deemed unfit to rule. Another method the Merovingians used to maintain legitimacy was the ceremony of having new kings hoisted up on a bulwark, or shield, by a group of soldiers; this was meant to symbolize the Franks giving this new king their consent to rule. Such efforts to legitimize their rule worked to great effect: the Merovingians retained the throne for over a century after their power first began to fade, partly because the Franks would accept no other family as their rulers.

Eventually, however, the Merovingians became eclipsed by the power of the aristocracy and the dynamic natures of certain mayors of the palace like Charles Martel (l. c. 688-741). In 751, the Merovingians had become irrelevant enough for Charles' son, Pepin the Short (r. 751-768) to seize the throne for himself and become the first Carolingian king of the Franks.

Origins

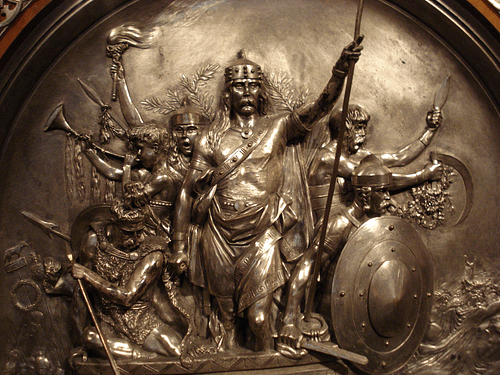

The Merovingian Dynasty originated as just one ruling family spread out across the loose confederation of Frankish tribes. The Merovingians belonged to the Salian Franks, a tribe that was settled in Belgic Gaul by the Western Roman Empire in 358 as foederati. Such an arrangement stipulated that the Salians had to provide the Romans with military service in exchange for use of land. Consequently, the Salians helped defend the empire's frontiers against barbarian incursions, and most famously participated in the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields against the Huns in 451.

This agreement with the Romans allowed certain Franks, and other foederati, to accumulate power within the existing Roman power structure. Certain individual "barbarians" rose through the ranks of the Roman army to attain high offices such as consul or magister militum (master of soldiers). Others simply solidified their power over the lands on which they had been settled, taking advantage of declining Roman authority. Chlodio, an early 5th-century leader of the Salian Franks, took the latter path; from his capital at Tournai, he expanded his influence over much of Belgium. Chlodio was able to entrench his authority by offering Gallo-Roman citizens protection and employment, things that could no longer be guaranteed by the Romans.

Chlodio died sometime before 451, at which point the Salians were being led by a certain Merovech who, according to 6th-century historian Gregory of Tours, was Chlodio's son. However, the Chronicle of Fredegar offers a different, fantastical account of Merovech's parentage; in the legend, Merovech was the offspring of a sea beast known as a Quinotaur, that forced itself on his mother while she was out swimming and impregnated her. The Quinotaur story, which may have been an attempt to connect the Franks with Greek mythology, also serves to give the Merovingians mythical origins, although there is no evidence that the story was told by the Merovingians nor that it was ever widely accepted. Outside of such myths, not much is known about Merovech except that he led the Franks against the Huns in 451 and that he was the father of Childeric I, who succeeded him as king of the Salians around 458.

There is evidence to suggest that King Childeric I (r. 458-481) maintained close ties with the Romans during his reign. In 463, he supposedly fought a battle at Orléans, possibly as a Roman ally. His military campaigns along the Loire are also often connected to the Romans, and a brooch was later discovered in his tomb that was only given to imperial officials of high standing. If Childeric truly was a Roman client or ally, he used this relationship to his advantage, greatly strengthening Salian power in northeastern Gaul. By the time he died in 481/82, the groundwork was laid for his son and successor, Clovis I, to conquer Gaul and unite the Franks.

Reign of Clovis

The reign of Clovis I was significant for two major reasons: his unification of the Franks, and his conversion to Christianity. The first project was begun in 486, when he attacked and defeated Syagrius, the last Roman official to wield power in Gaul, and captured the city of Soissons. From this new power base, Clovis campaigned against the Alemanni, defeating them at the Battle of Tolbiac in 496, and against the Visigoths, who he defeated at the Battle of Vouillé in 507. At Vouillé, Clovis curbed the power of the Visigoths, who were seen as a major threat to Frankish expansion, and extended his influence into Aquitaine.

After marrying Clotilde, daughter of a Burgundian king, Clovis campaigned in Burgundy, thereby expanding his influence further into Gaul. After his conversion, Clovis was recognized as an ally by the Byzantine emperor Anastasius I (r. 491-518), who awarded him with a consular office. During the later part of his reign, Clovis took over his neighboring Frankish kingdoms by employing a ruthless combination of conquest, cunning, and assassination. By the time of his death in 511, Clovis had claimed the title "King of All the Franks" and was master over most of Gaul, excepting only Burgundy, Provence, and Septimania on the Mediterranean coast. The Merovingian kingdom was established.

His second major achievement, his conversion to Catholicism, is traditionally said to have occurred in 496, the year of the Battle of Tolbiac. Prior to the battle, Clovis was a pagan who ignored every entreaty by his Catholic wife Clotilde to convert. At Tolbiac, when it became apparent that the Frankish forces were being defeated, the desperate Clovis prayed to God and vowed to be baptized if he could be granted victory. Immediately, the tide of the battle turned, and the Franks emerged victorious. True to his word, Clovis converted to Catholicism and was baptized alongside his sisters and 3,000 of his warriors.

This story, as told by Gregory of Tours, paints Clovis as a true convert, though many modern scholars believe that there were underlying political motivations. Clovis certainly knew that many of his new Gallo-Roman subjects were Catholics and perhaps wished to solidify his rule through conversion. His choice of Catholicism over Arian Christianity may have been done to justify his invasion of the Arian Visigoths by claiming to be the defender of Catholicism. Through this choice, he also gained access to several powerful Catholic allies including the Byzantine Empire. Whatever his motives, Clovis' conversion helped foster the growth of Catholicism over Arianism in Western Europe.

Sons of Clovis

After Clovis' death in 511, his kingdom was divided equally among his four sons, setting a precedent for future Merovingian successions. While this division is often explained as adherence to Germanic inheritance customs, scholar Ian Wood suggests that Queen Clotilde may have played a role in the partition to ensure her own sons would not be excluded from the succession. In either case, the partition would set a dangerous precedent for future successions which would become a major source of the rivalry and disunity between Merovingian kings.

Initially, Clovis' sons worked together to finish the conquests that their father had started. They conquered the Kingdom of Burgundy in 534 and were ceded control of Provence by the Ostrogoths a few years later. The Merovingians also expanded into Germany, conquering Thuringia in 531 and expanding their influence as far as Bavaria. The Saxons fought against the Merovingians in 555, but they were defeated and forced to pay the Franks a yearly tribute of 500 cows. These conquests made the Merovingians the largest and most powerful realm in the West following the death of Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great in 526.

Yet despite cooperating in these conquests, the sons of Clovis constantly looked for ways to undermine one another and enhance their own power. In 531, Theuderic I (r. 511-534) attempted to kill his half-brother Chlothar I (r. 511-561). When Theuderic died, Chlothar tried to seize his kingdom by force, and civil war was only avoided by a miraculous storm that hindered the armies. In 532, Chlothar and his brother Childebert I (r. 511-558) murdered two of their nephews to secure their own power. In 555, Childebert I incited Chlothar's son, Chramn, to rebellion, while Chlothar was off campaigning against the Saxons. Chramn's revolt ended in 560 when he was defeated by his father in battle and subsequently burned alive, alongside his wife and daughters, on the orders of Chlothar himself. This kind of infighting would become characteristic of the Merovingian Dynasty and would only worsen in the next generation.

By 558, Chlothar I had outlived his brothers and inherited their kingdoms, allowing himself to claim Clovis' old title "King of All the Franks". However, he would only rule over a reunited Merovingian kingdom for less than three years; upon his death in 561, the kingdom was once again partitioned among his four sons.

Rival Queens

By 567, the Merovingian kingdoms were ruled by three of Chlothar's surviving sons:

- Sigebert I (r. 561-575) reigned in the easternmost kingdom, soon to be known as Austrasia

- Guntram I of Orléans (r. 561-592) ruled over the territory of Burgundy

- Chilperic I (r. 561-584) ruled over the territory of Neustria from Soissons.

Both Sigebert and Chilperic were married to Visigothic princesses: Sigebert had married Brunhilda, and Chilperic wed Brunhilda's elder sister Galswinth. Yet Chilperic and Galswinth were not a happy couple, and it was not long before Chilperic had her murdered in order to marry his mistress, a servant named Fredegund. Galswinth's murder caused friction between Sigebert and Chilperic, which would boil over into civil war in 572.

The war lasted until 575 when Sigebert, on the cusp of achieving victory, was assassinated by two men likely hired by Queen Fredegund. Chilperic moved to take over Sigebert's kingdom but was stopped by Guntram, who guaranteed the independence of Sigebert's five-year-old son, Childebert II (r. 575-596). When Chilperic himself was assassinated in 584, Guntram offered similar protection to Chilperic's four-month-old son Chlothar II (r. 584-629). For a time, Guntram was the only adult Merovingian king and ruled all Francia in trust for his two nephews. When Guntram died in 592, this precarious peace was broken, and Childebert II invaded his cousin's kingdom.

This new round of civil wars was fueled by the young kings' mothers; the rivalry between Queen Brunhilda of Austrasia and Queen Fredegund of Neustria, which stretched back to the murder of Galswinth, had only deepened in the intervening years. The war between Childebert II and Chlothar II in 592 could be seen as a proxy war between the two queens; when Fredegund died in 597, Chlothar II continued the fight against his mother's rival. In 596, Childbert II died a mysterious death. His two sons (Brunhilda's grandsons) resumed the war against Chlothar II, eventually reducing his territory to just 12 counties between the Seine, the Oise, and the sea. But before the brothers could finish Chlothar off, they began quarreling with one another; after a bloody civil war in 612, both of Brunhilda's grandsons were dead, leaving the combined kingdom of Austrasia-Burgundy in the hands of the infant king Sigebert II and the elderly Brunhilda, who ruled as regent.

By this point, the Austrasian and Burgundian nobles were sick of Brunhilda's overbearing influence, and invited Chlothar II to invade, which he did in 613. After meeting little resistance, Chlothar II put Sigebert II to death. He had Brunhilda tortured for three days before she was tied to the limbs of horses and ripped apart. The gruesome execution of Brunhilda signaled the end to the conflict that had begun in 567 and allowed Chlothar II to reunite the Merovingian kingdoms under his own rule.

Rise of the Aristocracy

The reigns of Chlothar II and his son Dagobert I (r. 623-639) are considered by some historians to be the height of Merovingian power and a time of peace and prosperity for the Frankish kingdoms. Yet this success was achieved because of massive concessions given to the aristocracy that would weaken Merovingian crown authority over time. In 614, Chlothar II delivered the Edict of Paris, which decentralized power in his realm and gave more authority to regional elites. Then, in 617, more power was given to the mayors of the palace. This was an office that had originated as the head of the king's household but had risen to become the second most powerful position in the realm. There were three mayors in Chlothar's realm, one for each of the Merovingian kingdoms (Neustria, Austrasia, Burgundy). The concessions made in 617 allowed each mayor to legislate his own kingdom as he saw fit and forbade the king from legally removing a mayor from power. This, alongside the Edict of Paris, served to secure Chlothar II's own power by earning him the support of the aristocracy, but it also led to the long-term diminishment of Merovingian power by enhancing the authority of the aristocrats. It was, in the words of scholar Susan Wise Bauer, a "devil's deal" (251).

In 623, the Austrasian aristocrats began complaining that the king spent all his time in Neustria, arguing that the royal presence gave Neustria an unfair advantage. Since the Austrasian aristocracy had become too powerful to ignore, Chlothar decided to appease them by turning Austrasia into its own semi-autonomous subkingdom ruled by his eldest son Dagobert I. As king of Austrasia, Dagobert enjoyed minimal independence, since he was constantly subjected to the whims of the powerful Austrasian magnates. When Chlothar II died in 629, Dagobert became King of All the Franks and moved his capital from Metz to Paris, hoping to disempower the Austrasians. This only further vexed the Austrasians, who revolted against Dagobert's rule. In 634, Dagobert was forced to once again turn Austrasia into its own subkingdom and appointed his three-year-old son Sigebert III (r. 634-656) as its king.

Last Merovingians

When Dagobert died in 639, Sigebert III continued ruling in Austrasia while the crown of the combined kingdom of Neustria-Burgundy passed to Dagobert's younger son, Clovis II (r. 639-657). Since Sigebert and Clovis were both underage, the nobles of their respective kingdoms began to rule in their names. Thanks to the power given to the aristocracy during the reigns of Chlothar II and Dagobert, the magnates were able to further entrench themselves so that even once the young kings came of age, the mayors of the palace continued to run the show. Therefore, Sigebert III and Clovis II are sometimes considered the first of the "rois fainéants" or "do-nothing kings", so called for their lack of any real royal authority. The last century of Merovingian rule (639-751) saw the gradual erosion of Merovingian power until the kings were nothing more than ceremonial figureheads.

But even after the dynasty ceased to hold any actual power, the Merovingian name still meant something to their Frankish subjects. When Sigebert III died in 656, Grimoald, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, tried to put his own son on the throne. He had Sigebert's son, Dagobert II, tonsured and exiled to an Irish monastery before crowning his own son, known to history as Childebert the Adopted, as king of Austrasia. This angered the Austrasian magnates, who still refused to accept a non-Merovingian king; in 657, Grimoald and Childebert were captured by the Austrasian nobles and shipped to the court of Clovis II, who had them executed. Clovis then placed his own son, Childeric II, on the Austrasian throne.

As the decades wore on, Merovingian power continued to fade, as the authority of the mayors increased. One particular aristocratic clan, the Pippinids, rose to prominence as mayors of the palace. Charles Martel, a scion of the Pippinids and the founder of the Carolingian Dynasty, came to power as mayor of the palace of Austrasia in 715. Famous for leading the Franks to victory against the Umayyad Caliphate at the Battle of Tours (732), Charles Martel became the de facto ruler of Francia; for the last part of his reign, he did not even bother to appoint a puppet Merovingian king, and the throne remained vacant until Charles' death in 741. The dynamic reign of Charles Martel shattered the illusion that the Merovingians still had any power. In 751, the last Merovingian king, Childeric III, was deposed by Charles' son Pepin the Short. Pepin seized the throne for himself and became the first Carolingian king of the Franks.