The Saxons were a Germanic people of the region north of the Elbe River stretching from Holstein (in modern-day Germany) to the North Sea. The Saxons who migrated to Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries CE along with the Angles, Frisians, and Jutes came to be known as Anglo-Saxons to differentiate them from those on the continent.

The region they came from was referred to as Saxony, and their name is thought to derive from a type of knife they commonly used, known as a seax. The continental Saxons came into conflict with the Franks and were absorbed by them under Charlemagne after the Saxon Wars (772-804), while those who migrated to Britain established the kingdoms of Kent, Wessex (West Saxons), Sussex (South Saxons), Essex (East Saxons), East Anglia, and Mercia, with Middlesex (Middle Saxons) emerging later as part of Essex. Collectively, these people came to be known as Anglo-Saxons even though their communities were initially comprised of Angles, Frisians, Jutes, and Saxons. The term Anglo-Saxon initially had nothing to do with ethnicity and everything to do with clarity; as noted, it only designated those who had emigrated from Germanic territories to Britain and seems to have come into use primarily after 1066.

The Saxons were among the last European peoples to accept Christianity as they associated it with the Franks, their adversaries on the continent, but mainly because their belief system (Germanic paganism) was integral to their daily lives and social structure. Saxon adherence to pagan rites and traditions, even after their nominal conversion to Christianity in the 7th-9th centuries, influenced Christian observances just as their language contributed to the development of Old English in Britain.

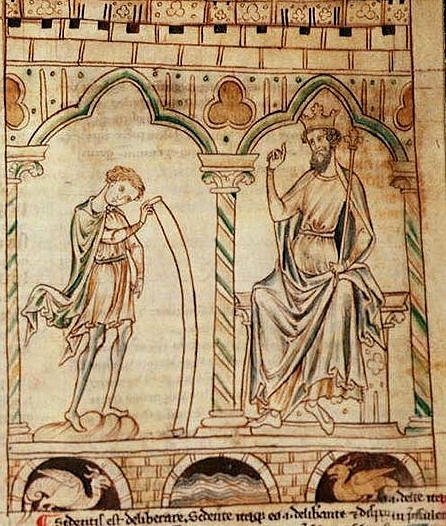

Anglo-Saxon kings, such as Alfred the Great (r. 871-899), encouraged literacy and the production of books in the English of that era until the Norman conquest of England in 1066 and the introduction of French as the language of the court, giving rise to Middle English which would eventually become modern English. On the continent, Saxon traditions continued even after they were conquered by the Franks under Charlemagne, influencing the development of Germanic culture and customs. In Britain, the Anglo-Saxon Period is dated to between 410-1066 – from the departure of the Romans to the Norman invasion – and on the continent from the 4th century to 804 (from their first mention in writing to their defeat in the Saxon Wars), but their legacy continued long afterwards and up through the modern era.

Origins

The Saxons are thought to have first been mentioned in the Geographia of Claudius Ptolemy (l. c. 100 to c. 170 CE), but it is possible he was referring to another people whose name was translated as Axones and later mistaken for Saxones because that name was better known. The most likely first mention of Saxones is in 356, referring to them as pirates along with the Franks, but no information is given on their origin. The Saxon chronicler Widukind of Corvey (l. c. 925-973), in his Deeds of the Saxons, writes:

First, I will present a little bit of information about the origin and status of the people. In this section, I am relying solely on tradition because the passage of so much time has clouded any certainty. There is a great deal of disagreement about this matter. (Ch. 2)

He then relates how the Saxons came from the Danes or from the Greeks or were Macedonian veterans from the army of Alexander the Great. All of these claims are rejected by modern scholarship. Widukind relates how they arrived at Hadeln (on the left bank of the lower Elbe River) by ship and came into conflict with the Thuringii living there. After several battles and many deaths, a treaty was concluded granting the Saxons freedom of trade in the region but prohibiting them from farming or establishing permanent settlements.

Widukind patterns his work on Greek and Roman histories and, in this section, either follows an earlier writer's lead or borrows freely from the tale of Queen Dido and the foundation of Carthage. He claims a Saxon youth, laden with gold, went to the Thuringii and said he would accept whatever they chose to give him for it. He was given a quantity of earth and returned to his ship. The Thuringii were delighted with the trade and thought the man who had made it quite clever, but the Saxon youth "took up the earth and spread it as thinly as possible over the nearby fields and then secured these places with fortified encampments" (Ch. 5). Since he had legally traded his gold for the earth, and the earth was now spread on the land, the land belonged to the Saxons and, when the Thuringii objected, the Saxons explained this and how they were within their rights to defend their property; and so the region of Saxony was established, and, according to Widukind, the Thuringii dramatically reversed their opinion on that gold-for-earth transaction.

Culture & Religion

How Saxony was actually founded or where the Saxons came from is unclear as the early Saxons left no written record. Widukind, writing much later, claims that, after the Saxons had established themselves, the Franks formed an alliance with them to defeat the Thuringii and then planned to turn on them. The Saxons heard of the plan, however, and slaughtered the Franks in a surprise attack. They then established the provinces that would become Angria, Eastphalia, and Westphalia of Saxony.

Information on Saxon culture and religion is also unclear. Their religion had no written scripture or liturgy and everything that is known of their traditions comes from later Christian writers. They seem to have practiced a form of Germanic paganism, which included veneration of a sacred pillar known as the Irminsul, which may have symbolized the World Tree (famous from Norse religion). Their chief god was Woden (Odin), and their religious rituals centered on the Irminsul erected in a sacred grove or on rituals observed in groves without the pillar. According to scholar Roger Collins, the Irminsul was "directly associated with military victory and conquest" and served to rally the Saxons for campaigns (281).

Saxon social structure was informed by religion as a hierarchy with nobles at the top, then freemen, then the lower class and slaves, based on the belief in higher, middling, and lower deities. Saxon law prohibited marriage between classes, but all three were fully represented at council meetings and had a voice in legal decisions and legislation.

Sacrifices were regularly made to the gods, and festivals were held annually on or around dates that were later Christianized – such as 25 December which was celebrated as Yule – and included the tradition of decorating trees and exchanging gifts. The Irminsul seems to have been understood to connect the underworld with the earth and on up to the heavens and so was honored as a symbol of the all-encompassing reach of the gods and their bond with humanity.

Migration, Piracy & Invasion Narrative

The Saxons, like many other peoples, were affected by the socio-political changes and population shifts of the so-called Age of Migration (or Migration Period) of the 4th-6th centuries. The Western Roman Empire was in decline during this period and formerly sedentary populations including the Alans, Alemanni, Goths, Huns, Slavs, and others clashed with each other and Roman communities as they tried to flee from invading forces, maintain cultural identity in a new land, and find secure regions with plentiful resources to establish communities.

Many of these groups had earlier allied themselves with Rome, sending soldiers as mercenaries in the Roman army, and among them were the Saxons, some of whom had already migrated to the coast of Gaul. Other Saxons, by this time, had long been engaged in piracy, along with the Franks and Frisians, from bases along the coast of the North Sea. These pirates regularly raided the coasts of Gaul and Britannia. According to some scholars, forts were built by the Britons to defend against these attacks, but this claim has been challenged, and it seems the structures that have been interpreted as forts were more likely trade centers, which were probably targets of Saxon raids.

Rome repeatedly sent forces against these pirates since Britain had been a Roman province since 43 CE and Roman interests needed to be protected. As the Roman Empire declined, it marshaled its resources closer to home, however, and did not have any surplus to send to Britain. The Gallo-Roman diplomat and poet Sidonius Apollinaris (l. c. 430 to c. 485) mentions the Saxon pirates and their raids on coastal towns and cities in his letters. Scholar H. R. Ellis Davidson comments:

A letter of Sidonius deplores the cruel custom of Saxon pirates, who would offer one prisoner in ten to the god of the sea as a thank-offering for a successful voyage. He admits, however, that they feel pledged to make their offering as a fulfillment of a vow: "These men are bound by vows which have to be paid in victims. They regard it as a religious act to perpetuate their horrible slaughter. This polluting sacrifice is, in their eyes, an absolving sacrifice." (64)

By 367, Frankish and Saxon coalitions had stepped up their raids, and attendant sacrifices, along the coast of Britain at the same time the Picts north of Hadrian's Wall began making more and more incursions into Roman Britain. Years before Sidonius was writing from Gaul, in 410, the Romans withdrew completely, and the Saxons began establishing permanent settlements in Britain by 429, but this does not seem to have stopped the raids of Saxon pirates on coastal ports. It may have been the actions of these pirates that led later medieval historians to craft their narrations of a Saxon invasion of Britain.

The Saxon migration has been characterized as an invasion, owing to the works of the historians Gildas (l. 500-570), Bede (l. 672-735), and Nennius (l. 9th century), the latter two drawing on the work of the first. Gildas depicts the Saxons as savages who were invited to Britain by its kings to deal with the Picts after the Romans left and then turned on their hosts. The Saxons then ravaged the land until they were defeated by the hero Ambrosius Aurelianus at the Battle of Badon Hill c. 460. Bede develops Gildas' version of events, and Nennius adds the detail of King Vortigern's betrayal by the Saxons and their defeat by the war chief Arthur at Badon Hill, a figure who would later be developed as the legendary King Arthur of the Britons.

Modern scholarship has challenged the narrative of a Saxon invasion as it seems increasingly certain that Saxons, Angles, Frisians, Jutes, and Britons lived together in Britannia and engaged in mutually beneficial trade. As noted, the 'forts' which were earlier thought to have been built for defense against the Saxons were probably trade centers, and archaeological excavations have determined peaceful trade in the interior between the Saxons and others who seem to have lived side by side.

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, the Saxon chief Cerdic of Wessex, and his son Cynric, arrived in Britain in 495, defeated the Welsh and then the Briton forces, and founded the Kingdom of the West Saxons (Wessex). Cerdic is recognized as the first king of this region, and many later genealogies of the English monarchy claimed him as their ancestor. Modern scholarship, however, has challenged the traditional interpretation of Cerdic as Saxon chief, noting that his name is British and he was most likely a British earl who had taken refuge with the Saxons, learned their language, and returned in 495 to reclaim a lost kingdom. The interpretation of Cerdic as a leader, or the leader, of a Saxon invasion of Britain has been largely debunked.

Whoever Cerdic was, however, he established one of the most vibrant Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the land. The Anglo-Saxons had first landed at Kent and established themselves there before moving on to settle other areas with their own governments. In Wessex, only a man who was descended from Cerdic could claim kingship from the time of his son Cynric down through the reign of Alfred the Great.

Alfred defeated the Vikings, first at Eddington in 878 and again at London in 886, and emerged as King of the Anglo-Saxons, governing all those regions not still held by the Danes. He unified his kingdom through his law code, upgrades to the infrastructure, trade agreements, and educational programs. His grandson, Aethelstan (r. 927-939), continued his policies as the first King of England, reigning over a diverse but unified people.

The Saxon Wars

On the continent, however, it was a different story as the Franks rose in power and the Saxons resisted efforts at assimilation. Charlemagne, as King of the Franks (r. 768-814), then King of the Franks and Lombards (r. 774-814), and finally as Holy Roman Emperor (r. 800-814), was not interested in diversity, only unity. Shortly after becoming King of the Franks, he launched a military campaign against the Saxons in 772 in an effort to eradicate Germanic paganism and Christianize Saxony. On the pretext that the Saxons had burned a church, Charlemagne invaded Westphalia and cut down the Irminsul there in an effort to break the Saxons' spirit. He then looted the shrine associated with the Irminsul and slaughtered any Saxons in his path as he marched away.

The Saxon Wars raged, on and off, for over 30 years as Charlemagne claimed victories, which the Saxons refused to recognize. In 777, a Saxon war chief named Widukind negotiated with King Sigfried of Denmark to allow Saxon refugees into his kingdom, which Charlemagne interpreted as a challenge to his authority, and hostilities resumed. In 782, he ordered the execution of 4,500 Saxons (the Massacre of Verden) to break their will and force them to abandon their traditions, accept Christianity, and submit to Frankish rule, but they continued to resist. Widukind disappears from the historical record after 785, and no other leader of note took his place.

In 798, Charlemagne halted all Saxon migration to Denmark and continued to pressure the people of Saxony to submit to his authority. When they continued to resist, he abandoned his usual policies and, in 804, had 10,000 Saxons deported to Neustria, replacing them in Saxony with Franks, and ending the Saxon Wars. The Saxons in Denmark, Neustria, and those left in Saxony then assimilated with the rest of the population.

Conclusion

Britain had become Christianized beginning in 597 with the arrival of St. Augustine of Canterbury and the conversion of the court at Kent, but Anglo-Saxon religious traditions, such as the observance of Yule, continued, as did folk beliefs, which were transmitted through stories that became folktales and legends, forming the basis for the development of English literature. The earliest European literary epic, Beowulf, is an Anglo-Saxon work as are other famous pieces of medieval literature such as Caedmon's Hymn. The literary tradition established by such works was later developed by writers including Geoffrey Chaucer and William Shakespeare.

Anglo-Saxon contributions to culture range from contract and property law to trial by jury, the construction of houses, the development of weaponry and armor (famously evidenced by the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial), and many others, but the term Anglo-Saxon has unfortunately been appropriated in the modern era by members of far-right organizations advocating white supremacy. It should be remembered that, by the time the Saxons enter the historical record, the Indus Valley Civilization and those of Mesopotamia and Egypt had already risen and fallen over a thousand years before. The legacy of the Saxons and Anglo-Saxons has and continues to exert a vital influence on world culture but should be understood in the context of global, not just European, history.