Leo III was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 717 to 741 CE. He founded the Isaurian dynasty which ruled until 802 CE. The emperor was a talented administrator, and he revamped the empire's political apparatus and legal code. Leo's reign also saw several conflicts with the Arab world beginning with the successful defence of Constantinople and ending in the reconquest of Asia Minor. The emperor is best remembered today for beginning the destruction of icons in the Christian church which his successors pursued with even more passion, leading to a widening of the gap between the western and eastern Church.

Succession

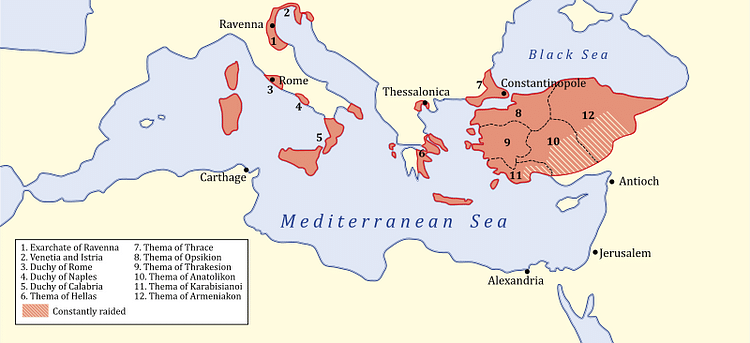

Leo, born Konon, was a shepherd in Thrace whose parents had relocated there from Syria. Despite his humble background, the ambitious Leo would push himself to the very top. A diplomat by the reign of Justinian II (r. 685-695 CE), he had assisted the emperor in regaining his throne in 705 CE after working his way up the ranks of the army. By the reign of Anastasios II (713-716 CE) Leo was the governor (strategos) of the military province (theme) of Anatolikon in central Asia Minor and, as such, had real political power. In 717 CE Leo joined forces with his fellow strategos Artabasdos, who governed Armeniakon in northeast Asia Minor. The latter was promised the title of curopalates, one of the three highest ranks in the empire if Leo's bid for ultimate power was successful. Facing and defeating a small army of the emperor at Nicomedia, the conspirators deposed Anastasios' successor, Theodosius III (r. 716-717 CE).

Theodosios was exiled to a monastery at Ephesus while Leo entered Constantinople in triumph as emperor on 25 March 717 CE. After the people had seen four emperors in six years, Leo would finally provide the empire with some stability. The new emperor was not, then, from Isauria (southern Asia Minor) but the later chronicler Theophanes the Confessor (d. c. 818 CE) described him as such, and the name has stuck for his dynasty, the Isaurian, which included three more emperors and one empress, lasting until 802 CE.

Military Campaigns

Leo's reign hit an immediate crisis when his capital Constantinople was besieged by an Arab force led by the brilliant general Maslama. Indeed, one reason why the Church and nobles of the empire so readily accepted Leo as their new emperor may well have been due to the imminent threat to the capital. The siege began in August 717 CE, conducted by an Arab army of 80,000 men and a fleet of 1,800 ships. It would last a year, but the city, protected by its formidable fortifications and the secret incendiary weapon of Greek Fire, withstood the onslaught. When the Bulgar khan Tervel sent a relieving force to aid his ally of convenience Leo, Maslama's army, already weakened by an unusually harsh winter, famine, and disease, was forced to withdraw on 15 August 718 CE. The saving of the city was commemorated each year, thereafter - Byzantium and the most important Christian city outside Jerusalem could breathe a huge sigh of relief.

Leo, having proven his defensive skills, next went on the offensive to try and regain some of the huge territorial losses the empire had sustained in recent decades. Attacking the Arabs in western and southern Asia Minor, he won several battles, notably at Nicaea in 726 CE. Leo's alliances with the Georgians and Khazars were proving very useful, especially the latter who, hailing from an area north of the Black Sea, could attack the rear of the Arab forces. The semi-nomadic Khazars had well-established ties with Constantinople, Justinian II having married the khan's daughter, and Leo sensibly ensured the good-relations continued by having his son marry one of the present khan's daughters. Then, in 740 CE, the decisive blow came, and the Byzantine army won a great victory at the battle of Akroinon in Phrygia which forced the Arabs to withdraw from the region. The conquered territories were organised into two new themes of the empire: Thrakesion and Kibyrrhaiotai.

Iconoclasm

The idea that the Christian worship of religious images is idolatrous goes back to the Old Testament but over the centuries icons (that is images of holy persons: Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary and saints) had become a normal feature of many churches. Leo III was the first ruler to involve himself in the debate, and he supported iconoclasm, that is the “breaking of images.” Quite what motivated Leo besides personal conviction is unclear. Byzantine Christian historians, all of whom, significantly, were in favour of icons, propose that the emperor was unduly influenced by Jews and Muslims, but modern historians discount this as unlikely. Alternatively, there may have been a belief that the terrible losses to the Muslim armies of the Arab Caliphate prior to Leo's reign were because God was displeased to see his image plastered on the walls of his churches and elsewhere. It may be that, as God's representative on earth, the Byzantine emperor merely wished to exercise his right as he saw it to dictate not only political policies but ecclesiastical ones too. The exact motivations are lost in the mists of time, but the consequences would resound for centuries.

Leo began his campaign of smashing icons with the biggest of them all, insisting that the golden image of Jesus Christ above the ceremonial entrance of his own royal palace, the Chalke, be removed. A riot of protestors broke out, and rumblings of discontent could be heard everywhere from Ravenna to Greece. A more formal statement of intent was needed, and so, in 730 CE, Leo officially decreed that all religious images and relics must be destroyed. To ensure his wishes were carried out, the emperor dismissed Germanos I, the Patriarch (bishop) of Constantinople who had objected to his decree and replaced him with Anastasios, a staunch iconoclast. Monasteries (which produced the icons), several bishops, and a great many ordinary Christians still wished to venerate their images, though, and a great rift in the Byzantine Church was opened which would only partially close towards the end of the 8th century CE and return again in 9th century CE.

As with most persecutions, the effect was to drive iconophiles underground and to continue their veneration in secret, although, Leo seems largely to have concentrated his efforts on destroying the images themselves rather than the people who venerated them. People who protested on the spot against the destruction of images at sacred sites were imprisoned, but iconophiles were not pursued individually - yet.

The popes had long been in favour of the use of icons in holy places and so it came as no surprise that Pope Gregory II protested about the policy, and his successor Gregory III, too, but without any effect. The popes were none too pleased either that a former shepherd was now deciding Church dogma. Leo pressed on regardless and used the debate as an excuse to withdraw the ecclesiastical administration of Sicily, Calabria, and Illyricum (in the Balkans) away from papal authority to that of the Patriarch of Constantinople. The Byzantine emperor sent a task force to Rome with the express purpose of arresting the Pope (it never got there, floundering in a storm), and the Pope responded by proclaiming anyone destroying icons would be excommunicated. It was the beginning of a messy, bitter, and irreconcilable split in the western and eastern Churches, not to mention one of the greatest assaults in history on art and religious relics.

Administrative & Legal Reforms

A keen and able administrator, Leo was fully aware that his own path to the throne might well be followed by another ambitious strategos, and so he divided some of the Empire's bigger themes into smaller units and centralised government in general to reduce the power base of the military governors. Anti-corruption measures were taken such as the introduction of salaries for judges to make them less liable to take bribes. In 721 CE coinage was improved by the addition of the silver miliaresion, worth one-twelfth of a gold nomisma (solidus).

Regarding other legal affairs, in 726 CE (or possibly 741 CE) Leo introduced a new manual on Byzantine laws called the Ecloga; replacing and updating the old and often contradictory Justinian code of 529 CE, its laws would not be superceded for another 150 years. One of the changes was to replace the practice of punishing many crimes with the death penalty for mutilations such as cutting off the nose, blinding, and removing a hand or the tongue. Below are some example laws relating to personal relationships from the new code:

- A married man who commits adultery shall by way of correction be flogged with twelve lashes; and whether rich or poor he shall pay a fine.

- An unmarried man who commits fornication shall be flogged with six lashes.

- A person who has carnal knowledge of a nun shall, upon the footing that he is debauching the Church of God, have his nose slit [cut off], because he committed wicked adultery with her who belonged to the Church.

- The husband who is cognizant of, and condones, his wife's adultery shall be flogged and exiled, and the adulterer and the adulteress shall have their noses slit.

(Gregory, 202)

Other legal reforms included making divorce more difficult, protecting the rights and property of married women, outlining an impressive list of sexual crimes and generally incorporating a strong influence from Christianity. Instead of the usual Latin, the new laws were written in the wider-known Greek language to help their practical application in everyday life by judges, governors, and lawyers across the empire; the Ecloga was also translated into the Armenian and Slavic languages, amongst others. It was the first time that ordinary people could access and understand the laws according to which they were supposed to conduct themselves.

Death & Successor

Leo made his son Constantine co-emperor in 720 CE and put him on Byzantine coinage to spread the message that a dynasty had been founded. When Leo died in his sleep in 741 CE - a rare luxury for a Byzantine emperor - Constantine took his rightful place, and he would reign as Constantine V until 775 CE. He continued his father's military successes, notably against the Bulgars in the Balkans and the Arabs in Syria and Armenia. Constantine continued to vehemently attack the veneration of icons but went even further than his father, insisting only the True Cross was a suitable image to be seen within churches and actively persecuting iconophile Christians.