Constantine VII was Byzantine emperor from 945 until 959 CE. Sometimes known as Constantine Porphyrogennetos because of his birth in the purple chamber of the royal palace, he was served by various regents from 912 CE until reigning in his own right after a 33-year wait. Known for his prolific writing and as a sponsor of literature and the arts, the emperor's reign was a successful one and included notable victories against the Arabs in Mesopotamia.

Succession & Regents

Constantine was born in 906 CE; his mother was Zoe Karvounopsina, fourth wife of emperor Leo VI (886-912 CE). As such, the emperor was a member and fourth ruler of the Macedonian dynasty founded by Basil I (r. 867-886 CE). Constantine, as was the tradition, had already been crowned co-emperor by his father in 908 CE, and when Leo died on 11 May 912 CE, his only male heir, Constantine VII, took the throne just a few days shy of his eighth birthday.

Constantine VII, like his father Leo VI, was “born in the purple” or porphyrogennetos. The phrase derived from the porphyry, a rare purple-laced marble, that was used in the chamber of the palace at Constantinople where Leo's birth, and many subsequent ones, took place. The restriction that only royalty wore robes made with Tyrian purple dated back to Roman times, and this new tradition was one more attempt to further reinforce the legitimacy of dynastic succession and deter would-be usurpers. With many regents and pretenders to his throne, Constantine's claim to legitimacy would prove a very valuable one indeed.

Because of his young age, Constantine's uncle Alexander acted as his regent. Alexander, a drunken roisterer infamous for his cruelty and debauched lifestyle, died in 913 CE while performing pagan sacrifices in the Hippodrome of Constantinople. It was just as well for the young Constantine as Alexander had boasted he would have the boy castrated. Constantine's next regent was Nicholas I Mystikos, the Patriarch (bishop) of Constantinople, with one of Nicholas' first acts being to dismiss his rival the emperor's mother to a convent. Zoe was shorn of her hair and henceforth would only be known as Sister Anna. Although a revolt led by the usurper Constantine Doukas was quashed, the bishop proved inadequate in responding to the threat of Symeon, Tsar of the Bulgars, who was as troublesome now as he had been during Leo VI's reign. Symeon's armies were almost at the gates of Constantinople, and the reeling empire was obliged to meet his peace terms which included marrying his daughter to Constantine VII.

A faction of the Byzantine court baulked at the idea of merely handing over power to the Bulgar emperor and staged a coup d'etat. Consequently, in February 914 CE, Constantine's mother returned from the political wilderness, called off the proposed marriage alliance and acted as her son's third regent. Zoe, although enjoying some military success against the Arabs, turned out to be just as ineffectual in staving of the Bulgars' renewed attacks in the Balkans and Greece, and she was forced to step down in 919 CE, undergo another haircut and retreat back to her nunnery. Romanos I Lekapenos, commander of the Byzantine navy, took his chance and became regent number four in 920 CE. He enjoyed certain successes against the Arabs in Mesopotamia, capturing Melitene, Nisibis, Dara, Amida, Martyropolis, and Edessa. To cement his position, Romanos had his daughter Helena marry Constantine, had himself crowned co-emperor and declared senior to Constantine, and then even had his three sons crowned as co-emperors.

Romanos may have initially been planning to found a new dynasty of his own, but the project was practically sunk when his eldest and most capable son, Christopher, died in 944 CE. The co-emperor's other sons were too young and useless, and it seems likely their father planned to at last release the throne to its rightful occupant, Constantine VII. Romanos had, after all, a stake already in the Macedonian dynasty now that his daughter was empress. However, Romanos' two remaining sons had other plans and themselves staged a coup in 944 CE in which they exiled their father to a monastery. Fortunately for Constantine, there was significant support at court to return the throne to the legitimate line of descent, and the Romanos boys were kicked out of Constantinople on 27 January 945 CE. Constantine could finally take the throne in his own right, aged 39: it was better late than never.

Land Reforms

Constantine continued the agrarian reforms of Romanos I and sought to rebalance wealth and tax responsibilities, thus, the larger estate owners (dynatoi) had to return lands they had acquired from the peasantry since 945 CE without being given any compensation in return. For land acquired between 934 and 945 CE, the peasants were required to repay the fee they had received for their land. The land rights of soldiers were likewise protected by new laws. Because of these reforms “the condition of the landed peasantry - which formed the foundation of the whole economic and military strength of the empire - was better off than it had been for a century” (Norwich, 183).

Military Campaigns & Diplomacy

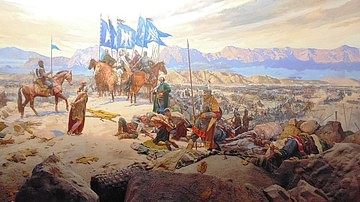

Constantine's foreign exploits usually saw him face the now familiar enemy of the Arab Caliphate as, fortunately for the Byzantines, Symeon the Bulgar had now been succeeded by the more accommodating Peter and a peace treaty was signed eliminating that particular enemy of the empire. 949 CE saw a failed attempt to take Crete, but Germanikeia on the Mesopotamian frontier was captured the same year. In 953 CE Germanikeia was lost again, but several victories came in the following years, thanks to the able generals Nikephoros II Phokas and John I Tzimiskes, both of whom would be future emperors. Nikephoros, particularly, enjoyed such successes that he became known as the “Pale Death of the Saracens” and even a rumour of his army merely mobilising caused the Arabs to retreat. In 958 CE Tzimiskes led a force which captured the strategically important Samosata on the upper Euphrates river.

The Byzantine Empire was regaining some of its lost lustre and Constantine's court began to attract dignitaries eager to see for themselves this learned young emperor who had set Constantinople back on its feet. The historian L. Brownworth makes the following comments on the diplomatic sparkle Constantine showered on his visiting peers from foreign powers:

Dignitaries and ambassadors from the caliph of Cordoba to the crowned heads of Europe came flocking to Constantinople, where they were dazzled with the breadth of the emperor's knowledge and the splendor of his court. Entertained in the sumptuous palace known as the Hall of the Nineteen Couches, visiting guests would recline to eat in the ancient Roman fashion, clapping in wonder as golden plates laden with fruit would be unexpectedly lowered from the ceiling. Cleverly concealed cisterns would make wine splash from fountains or cascade down carved statues and columns, and an automatic clock in the city's main forum would complete the imperial tour de force. Most impressive of all, however, was the emperor himself. (188)

Literature & Arts

Constantine VII gained a reputation as a great scholar, and we know he was a collector of books, manuscripts, and artworks, and an accomplished painter, too. His most famous written works are the De administrando imperio, a handbook for rulers and diplomats (especially aimed at his son and heir) which includes notes on the cultures bordering the empire, the De thematibus, on the geography and history of the empire's various provinces, and the De ceremoniis on the protocols and ceremonies of the Byzantine court. Constantine drew on many earlier works, and his own thus preserve a rich Byzantine heritage, undaunted as he was by the task of sifting through the immense imperial archives, as he himself states in one of his books:

Research into history has become clouded and uncertain, either because of the scarcity of useful books or because the quantity of written material has aroused fear and dismay. (Herrin, 182).

The emperor sponsored the literary works of others, notably the Geoponika encyclopedia on agriculture and the catalogue of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople by his asekretis (imperial secretary), the poet Constantine of Rhodes. Another important commission was the Synaxarion, a comprehensive calendar of saints, each figure having a short biography. Constantine revived the Magnaura university within the royal palace, which had four chairs: philosophy, geometry, astronomy, and grammar. Historians were another group supported by the emperor, including such noted figures as Genesios and Theodore Daphnopates. One of the most important histories of the period is the anonymous Theophanes Continuatus, a chronicle of Byzantine rulers and events from 813 to 961 CE.

Constantine was especially keen not to have any tarnish spread to his own image from some of his more dubious predecessors in the Macedonian dynasty, especially its founder Basil. Consequently, he wrote the whitewashed biographical Vita Basilii which became the accepted historical record of Basil's life and achievements. Besides his own literature, Constantine also supported other arts, especially the production of illuminated manuscripts and carved ivories.

Death & Legacy

Constantine's reign was a successful one, and he is remembered today as one of the more accomplished Byzantine rulers, as the historian J. J. Norwich here summarises:

He was an excellent Emperor: a competent, conscientious and hard-working administrator and an inspired picker of men, whose appointments to military, naval, ecclesiastical, civil and academic posts were both imaginative and successful. He did much to develop higher education and took a special interest in the administration of justice. That he ate and drank more than was good for him all our authorities seem to agree; but there is unanimity, too, on his constant good humour: he was unfailingly courteous to everyone and was never known to lose his temper. (181)

When Constantine died of natural causes on 9 November 959 CE, he was succeeded by his 20-year old son with Helena Lekapenos, Romanos II. Unfortunately for Romanos, his reign would be a short one, and his throne passed to his two young sons Basil II, “the Bulgar-Slayer”, and Constantine VIII in 963 CE, who would continue the Macedonian dynasty for another half-century.