Voltaire (1694-1778) was a French author, historian, and philosopher whose thoughts on religious toleration and moderation of authoritarian power were influential during the Enlightenment. His most famous work today is the satirical Candide, which presents Voltaire's critical thoughts on other philosophers, the Catholic Church, and the French state in order to highlight the need for real solutions to everyday problems.

Early Life

François-Marie Arouet, better known by his chosen pseudonym Voltaire, was born in Paris on 21 November 1694. Françoise-Marie's father was a notary who sent him to the highly esteemed Louis-le-Grand college, then run by Jesuits. Going on to study law, Françoise-Marie's real interest was literature, and he was soon writing his own poems and plays. These early offerings were the beginning of what would turn out to be a momentous catalogue of works of all kinds by the end of Voltaire's long career.

In 1718, Voltaire's first play, Oedipus, was successfully staged, and he had his first poem, La Henriade, published to great acclaim in 1723. Voltaire might have had literary aspirations, but his fledgling career took a nosedive in 1726 when, after an argument with the Chevalier de Rohan, he was confined in the infamous Bastille prison. When he got out, Voltaire decided to broaden his horizons, and he visited first the Netherlands and then England, where he lived until 1729.

Philosophical Ideas

Voltaire's three years in England saw him embark on a more philosophical approach to literature. He wrote his Letters on England (aka Philosophical Letters) based on his experiences in that country. The Letters was published in 1734 and favourably compared the relative openness and liberalism present in England compared to France. Voltaire argues that different denominations of Christianity should be tolerated in the same society. This is based on his belief that toleration springs from no single group being able to claim absolute truth. He proposes that the best form of government is a monarchy limited in its power by a parliament and constitution. Voltaire believes that because humans are rational and act with reasonable self-interest, they should be given more liberty than current authoritarian government systems allow. He also gives biographies of four leading thinkers who influenced the later Enlightenment: Francis Bacon (1561-1626), John Locke (1632-1704), Isaac Newton (1642-1727), and René Descartes (1596-1650). In summary, Voltaire argues that the greater freedom and toleration he has witnessed in England compared to France is also the reason why that country is more prosperous and its citizens happier. The French Parlement did not take kindly to this assessment, and Letters on England was condemned.

Madame du Châtelet

Voltaire had returned to France, but given the uproar his Letters on England had caused with the Establishment, he was obliged to seek obscurity for a while. He lived with Gabrielle Émilie, Marquise du Châtelet (1706-1749), who first translated Newton's Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy into French. The two had met in 1733, and in 1734, Voltaire stayed with the marquise in her country retreat of Cirey in the Champagne region. Together, they pursued their mutual interest in biblical studies, history, and physics. The couple's romantic relationship, besides the complication of the marquise's husband, survived the presence of another love interest, Jean François de Saint-Lambert. Voltaire finally left Cirey in 1744. The marquise became pregnant with the child of Jean François, but she died giving birth in September 1749.

Encyclopedia & Rulers

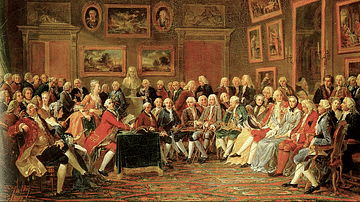

Voltaire was appointed the royal historiographer in 1745, a position he kept for two years. In 1746, he was elected to the prestigious Académie française and to the Accademia della Crusca in Florence. Voltaire contributed to the 17-volume Encyclopédie, published from 1751 and regularly expanded. This influential new compendium of knowledge, edited by Denis Diderot (1713-1784), presented provocative new ideas in philosophy and science.

Voltaire also involved himself in politics in the 1740s, typically in the form of diplomatic missions on behalf of the government. Keen to see firsthand how authoritarian rulers operated, Voltaire spent time at various royal courts, most notably Frederick the Great, King of Prussia (r. 1740-1786). Voltaire was interested in observing what historians later called 'enlightened despots', even if they rarely or ever achieved precisely what Voltaire and others proposed as the best strategies of statecraft for a fairer and happier society. Voltaire got into serious trouble in Prussia, involving himself in a scandalous legal case and taking a compromising book of Frederick's private poems without the ruler's permission (he was arrested and forced to return it). Ultimately, Voltaire wisened up to the darker side of monarchs, lamenting in a 1775 letter to Frederick: "You kings, you put us on our guard, you are like Homer's gods who make men serve their purposes without these poor people suspecting it" (Robertson, 668).

The tendency for some rulers to court philosophers and try to modernise their respective states (if only in the sense of abolishing some of the harsher medieval conventions) at least indicates that the Enlightenment was beginning to shine on practical politics and reflected "a rise in the status of intellectuals, and a new awareness of the potential uses of knowledge by those in power" (Chisick, 156).

The Great Historian

From 1755, Voltaire lived near Geneva in a château, such was his success. Essai sur les moeurs et l'esprit des nations (Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations) was published in 1756 but constantly revised by Voltaire, who seems to have considered it his greatest endeavour. Actually a work of history, Voltaire summarises European history from the 8th century to the early 18th century and so earned a reputation as one of the great historians of the Enlightenment. The history attempted to shift the usual focus on religious affairs and wars to a more secular treatment of cultural events. Voltaire refused to give rulers and generals the traditional prominence other historians had given them. Another innovation was that Voltaire considered the history and cultural practices of states typically ignored by European authors, such as China, India, and various Islamic states. These exotic cultures were often used to demonstrate that the French were not quite as enlightened as they thought they were and to show that claims that Christian ideals had a monopoly on how best to live were nonsense.

Candide

Voltaire pioneered a new form of literature, the conte, a short and imaginative flight of fancy similar to ancient oral storytelling. The conte genre allows a writer to present serious ideas in an exotic or fanciful setting that both entertains the reader and sets them thinking. Voltaire's masterpiece in this new style was Candide, published in 1759. It is an often pessimistic work that sees the gradual disillusionment of the naive central character, Candide, who travels around the world in pursuit of his love Cunégonde. Through the story, Voltaire presents withering criticisms of the French state, especially the nobility, as well as the Church, and particularly his old school chums, the Jesuits. Others to feel the wrath of the author's pen include owners of Caribbean sugar plantations where slave labour is used and intellectuals who insist on defending an obviously defunct status quo. The single ray of hope Voltaire presents is that if we recognise the harshness of life, we can do something about it using reason to make practical improvements. Voltaire rejects the lofty utopian thoughts of other thinkers (especially Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz) in favour of simpler and more practical solutions to society's present problems. Despite the pessimism, Voltaire was confident that reason was being used as never before in his own lifetime, a period he described in another work as "the most enlightened age the world has ever seen" (Gottlieb, 238). Candide's other title was, after all, L'optimisme. Candide was a roaring success, and in its first year alone, the publishers were obliged to print eight editions. The book was translated into English in 1759. Meanwhile, Voltaire returned to history and worked on a flattering biography of Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725).

Final Thoughts

In 1759, Voltaire returned to France and lived at Ferney, near the French border with Switzerland. Here, he spent a great deal of time gardening when not writing. Voltaire published his Treatise on Tolerance in 1762 and Dictionnaire Philosophique (Philosophical Dictionary) in 1764. Here, like in his other works, he attacks superstition, metaphysics, religious dogma, and the dangers of authoritarian governments. The latter work is curious since it is neither a dictionary nor particularly philosophical, but rather a loose collection of articles (which Voltaire kept adding to in each new addition) providing enlightened readers with countless reasons why the Old Regime of France needs changing. It is in this work that Voltaire most clearly presents his view on morals.

Voltaire was a deist, that is, someone who believes in the presence of God as a creator but believes that, much like a watchmaker who then abandons his work, God is not available for communication or interaction in the world he has created. This led to Voltaire erroneously believing that life as we know it was unchanging, that is, for example, all species had always been the same since the Creation. Another consequence of Voltaire's thought of God's abandonment was that evil and misfortune will forever persist in plaguing humanity. One such catastrophe was the devastating Lisbon earthquake on 1 November 1755, which moved Voltaire to write another work disparaging the belief that ‘everything happens for the best', his Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne (Poem on the Disaster of Lisbon).

Voltaire believed that God had given all humans an innate need for a moral code (although not the code itself), which they create, employ, and abide by because they possess reason. What Voltaire did not believe in was the trappings of man-made religion. He states in the Philosophical Dictionary that religion "is the source of all the follies and turmoils imaginable, it is the mother of fanaticism and civil discord; it is the enemy of mankind" (Gottlieb, 233).

For Voltaire, there is a God, but that deity is unknowable, as are many things we know exist, such as the universal law of gravity. He again expresses his despair at never being able to grasp certain fundamentals in his Philosophe ignorant (Ignorant Philosopher), published in 1766:

Who are you? Where do you come from? What are you doing? What will become of you? This is a question one must put to every creature in the universe, but none of them give us any answer.

(Hampson, 122)

Voltaire, just as he had sought out practical experience to confirm his political views, was also willing to test his ideas on religious toleration in the crucible of a court of law. Through the 1760s, Voltaire took up the cases of three infamous miscarriages of justice involving Jean Calas, Chevalier de la Barre, and the Sirven family. Voltaire used the cases, all involving Catholic intolerance, as inspiration for more writings on the necessity of reasoned tolerance in society. His appeal for tolerance, particularly of Protestants, is summarised in this passage from the Treatise on Tolerance:

Is each individual citizen, then, to be permitted to believe only in what his reason tells him, to think only what his reason, be it enlightened or misguided, may dictate? Yes, indeed he should, provided always that he threatens no disturbance to public order.

(Robertson, 125)

Voltaire's Major Works

The most important works of the philosopher Voltaire include:

- Oedipus (1718)

- La Henriade (1723)

- Letters on England (1734)

- Zadig (1747)

- Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations (1756)

- Candide (1759)

- Treatise on Tolerance (1762)

- Philosophical Dictionary (1764)

- Ignorant Philosopher (1766)

Death & Legacy

Voltaire spent his final day on this earth in Paris, having just returned to the city of his birth the night before. He had accumulated great wealth through his literary career and banking activities, wisely investing in ever grander estates and so eventually becoming a part of the lower nobility. He died on 30 May 1778. Voltaire's remains were interred in the crypt of the Panthéon in Paris in 1791. This act of honour was carried out by the revolutionaries of the French Revolution, which is rather ironic since Voltaire would have been aghast at the trial and execution of Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) two years later. Voltaire's ideas on the dangers of authoritarian government and the abuses of church power had appealed to the revolutionaries, but he had never been a man of the people. As he once wrote in a letter to a friend: "Enlightened times will enlighten only a small number of honest people. The vulgar masses will always be fanatics" (Gottlieb, 233).

According to the historian H. Chisick, Voltaire, "more than any other represented the Enlightenment to his contemporaries" (430). Less an original philosopher and more a destroyer of the old attitudes that permitted fellow thinkers like John Locke to flourish, Voltaire has earned his place among the great group of French-speaking philosophes, which includes Montesquieu (1689-1757), Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), and Diderot. As the latter once stated: "we live in a century in which the philosophical spirit has rid us of a great number of prejudices" (Robertson, 27), and Voltaire had done more than most to challenge those prejudices.