Although there are certainly differences between Eastern and Western philosophical systems, they both aim at the same goal of apprehending Truth and understanding the best way to live one's life. Modern-day scholarship often makes a serious, and arbitrary, distinction between the two which is unnecessary and erects an artificial boundary between the two traditions.

Since the 'discovery' of eastern philosophy by western explorers and scholars in the 18th and 19th centuries CE, there has been an arbitrary division maintained, especially in colleges and universities, between 'western philosophy' and 'eastern philosophy' as though these two systems present radically different views of the world.

There is no division between eastern or western philosophy when it comes to the most basic questions of what it means to be a human being. The fundamental purpose of philosophy is to find meaning in one's life and purpose to one's path, and there is no major difference between eastern and western philosophy according to that understanding.

The Purpose of Human Existence

The similarities between eastern and western philosophy are greater than any differences cited by modern-day writers and lecturers on the topic. The most often cited difference is that western philosophy is 'fragmentary' while eastern philosophy is 'holistic'. The popular writer Sankara Saranam, author of the book God Without Religion, is one example of this when he claims that eastern philosophy is concerned with general knowledge while western philosophy aims at specific knowledge. This refers to the popular understanding that eastern philosophy - specifically Chinese philosophy - addresses the whole of human existence while western philosophy - beginning with the Greeks - only focuses on certain aspects of the human condition.

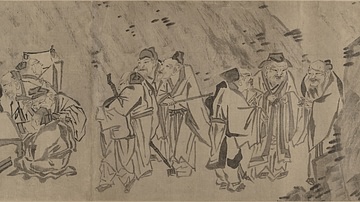

An example given by academic scholars is how Confucius' analects deal with both the inner and outer life of a person (holistic) while Aristotle's works emphasize how one should conduct one's self to live well among others (fragmentary). Mo-Ti, some claim, aims at a holistic understanding of one's self and one's surroundings while a western philosopher like Plato emphasizes specific goals one should strive for in discovering what is true and real in life.

These are arbitrary distinctions which totally miss the underlying, and essentially identical, aims of eastern and western philosophy. Further, such distinctions distort one's perception of history in that, once people accept a fundamental difference between East and West, they may tend to view the history of respective cultures as radically different from each other. In fact, human beings are essentially the same the world over, only the details and customs differ, and the philosophies of eastern and western thinkers make this quite clear.

One could compare the fundamental ideas of the great Chinese philosopher Confucius (l. 551-479 BCE) with those of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE) and find they are presenting the same basic concepts. Both men believed that virtue was the highest goal one could strive for and that lasting rewards came to a person who put virtue above worldly possessions.

The Korean philosopher Wonhyo (l. 617-686 CE) wrote, "Thinking makes good and bad" meaning that if you think something is 'bad' then it is bad to you. The Greek philosopher Epictetus (l. c. 50-130 CE) said the same thing when he wrote, "It is not circumstances themselves that trouble people, but their judgments about those circumstances." (Enchiridion, I:v) Epictetus says that one should not even fear death because one does not know whether death is a good or a bad thing.

Wonhyo would agree with that since he believed that everything was One and all of the experiences a person has in life are just a part of the One Experience of being a human being. The relativist philosophies of the Chinese sophist Teng Shih (l. 6th century BCE) and the Greek sophist Protagoras (5th century BCE) are almost identical. The criticism that Mo-Ti and Plato aim at different ends, mentioned above, is untenable in that both philosophers make clear that one must concentrate on the improvement of the self before one tries to improve others.

Innate Morality

The best example, however, of the fundamental sameness of eastern and western thought is epitomized in the works of two of the best-known philosophers from their respective hemispheres: Plato (l. 428-348 BCE) of the west and Wang Yangming (l. 1472-1529 CE) of the east. While Plato is quite well known in the west, Wang Yangming is less so, even though he is as famous as Plato in China, Korea, and Japan.

Both of these philosophers have exerted an enormous influence through their works, and both argue for the existence of innate knowledge; that human beings are born knowing right from wrong, and good from bad, and need only be encouraged to pursue goodness in order to live a fulfilling life. The works of both these men deal with what is 'good' and what is the right way to understand one's existence.

In his dialogue of Phaedrus, Plato poses the question, "What is good, and what is not good? Need we ask anyone to tell us these things?" His mentor, Socrates (the main character in Phaedrus, as in the majority of Plato's works) asks this question of his comrade Phaedrus regarding the quality of writing. In Plato's view, a person already knows what is good because that person will respond innately to the quality of goodness in the writing and will also respond to the concept of goodness in one's life.

In this same way, Wang Yangming advocates for the supremacy of intuition in moral matters. Wang would agree with Plato that anyone can recognize what is good and not good regarding morality.

Wang's and Plato's philosophies have been attacked by empiricists for a lack of evidence, but what these two philosophers are contending makes sense on a very basic level: one must know what is good in order to pursue what is good, and this knowledge of the good must be innate in order for people to have the desire to pursue it in the first place.

Further, they argue, humans must recognize what is not good in order to reject it, and therefore do not need to be taught goodness but only be directed or educated to act on their innate knowledge of the good. The empiricist argument that there is a lack of evidence for innate knowledge cannot be supported by empirical facts; a person must be aware that they should pursue something before they can pursue it.

Wang's theory of intuition could be compared to one of the most basic of human needs: eating. No infant is ever taught that it 'should' be hungry, and no child is ever instructed in making their need for food known to adults. The infant cries to let an adult know that it must be fed, and the child verbalizes that same need in words or deeds, such as saying, "I am hungry," or going to get something to eat.

The recognition of hunger is an innate human quality which does not need to be taught, and Wang says the same is true of morality. All that must be taught is how to apply that innate knowledge appropriately, in the same way that a child is taught the appropriate way to ask for food.

Conclusion

In Plato's Meno, Socrates praises a slave who knows geometry although he has never been taught it. Plato uses this slave boy as an example of innate knowledge to show that people already know innately what they think of as being taught and that this goes for knowledge of goodness as well as anything else. Just as a child knows when it is hungry, a person knows how to be good. Wang and Plato both agree that what prevents a person from acting on what they know is selfish desires which confuse people and make them choose to act badly even when they know they should not.

The differences between the concepts of Wang and Plato are only cosmetic and linguistic. There is no difference in their fundamental ideas. Philosophers from the east have always been engaged in exactly the same pursuit as their counterparts in the west. There is no 'eastern' or 'western' philosophy; there is only philosophy. The love of wisdom knows no separate region; philosophy defies all boundaries and every kind of petty regional definition.