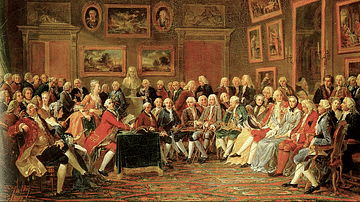

The salon was a notably French cultural event, a private social gathering where a mixture of guests openly discussed art, literature, philosophy, music, and politics. Salons were particularly but not exclusively associated with Paris and were most often hosted by wealthy and well-connected women.

The salon guests came from varied backgrounds, and so, as there was a democratic, cosmopolitan, and tolerant atmosphere to the proceedings, salons were an opportunity to hear different views from varied levels of society. They were also an opportunity to encounter new ideas, sometimes radical ones, in various fields, and so they contributed to the spread of Enlightenment thought. The salon certainly became a cultural institution, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, not only in France but also in several other European cities and in North America.

Development of the Salon

Salons became popular in Paris from the early 17th century. The term 'salon', however, was not used prior to the 18th century, and it is not to be confused with the contemporary Parisian public exhibitions of art that went by the same name. Typically hosted by aristocratic women, the weekly salon gatherings were for invited guests only and were held in special rooms where guests could mingle and talk in small groups. The historian W. E. Burns explains that "their original mission was the refinement of manners, speech, and literature" (285). Over time, a consideration of the arts, philosophy, and sciences came to be an important function of the event. Despite their often weighty intellectual pursuits, salons remained informal gatherings. Besides the food on offer, guests could hear musical performances by noted or up-and-coming musicians. Writers were encouraged to give readings of their latest work. There could be dancing, short acted dramas, intellectual debates, mimicry, and card and parlour games. Other guests included high society members, and while some hosts did separate guests based on social rank (either in different rooms or having them come to alternate salons), others did allow a mix between classes. Women were invited, too, which was another factor in making salons a genuine potpourri of gender, social status, and talent.

As a forum for new ideas, salons may have contributed to the European Enlightenment movement when traditional views began to be challenged by reason and science. The salons helped the spread of ideas by connecting writers to publishers, thinkers to other thinkers, and they gained many intellectuals the financial means to carry on their pursuits of knowledge. Given their openness as to who came along to their salons, hostesses often contributed as "catalysts for political and cultural tendencies" (Yolton, 471). In short, radical ideas did not always stay within the walls of the salon. The historian J. W. Yolton explains further:

Owing to their social permeability, salons became important forums for pre-Revolutionary thought in France. After the demise of court patronage, but preceding the maturity of the publishing industry, salons also functioned to help publishers, patrons, and readers to seek out authors to help to produce and distribute their works.

(471)

It should be remembered that salons were not established for intellectual reasons alone and that they were primarily social events. This latter fact has led some historians like R. Robertson to state that:

However diverse such gatherings were, they were of considerable importance for cultural life. It does not follow, however, that they contributed equally to the development of Enlightenment thought, and their significance in this respect may have been exaggerated.

(363)

The Role of the Hostess

As Yolton puts it: "In all salons the central figure was the hostess, often a mature woman of flair and authority. Her personal appeal and social ambition, her organizational skills, intelligence, wit, and good taste determined the ambiance" (471). Hosts were, too, of course, responsible for just who was invited to their weekly or twice-weekly gatherings.

Salon hosts were usually wealthy, well-connected, and with the required time, space, and money to pay for the refreshments. There were some male-only salons, such as those hosted by Baron d'Holbach (1723-1789) in his lavish Paris home, but the most famous ones were led by women. Several hostesses, or salonnières as they were known, became internationally famous for their salons. It is noteworthy that in a period when husbands still dominated their wives in almost every aspect, many (but certainly not all) salonnières had the freedom to organise public events because they were widows or separated from their husbands. There were some married salon hostesses, and there were unmarried hostesses, too.

Many of the women who hosted salons were friends with the intellectuals and artists they invited to their salons and some maintained a correspondence that lasted years. In addition, many acted as patrons, either through finance or direct recommendations to key decision-makers. Add to this the unique opportunity they were providing for exposure to artists and thinkers, and it is no surprise that these women became "power brokers who few could afford to ignore" (Chisick, 378).

Hostesses could also offer their own entertainments besides their charm and wit, such as one lady who kept chameleons in a heated cage so that guests could marvel as they changed their colours. Salon women did receive some unkind treatment in literature and the press. The playwright Molière (1622-1673) wrote The Learned Ladies in 1672, a satire that ridiculed women's interest in intellectual matters.

Les Salonnières

Some of the key salon hostesses are considered below.

Madame Anne Thérèse de Marganat de Courcelles, Marquise de Lambert (1647-1733) very much set the model for later salons, although she had one gathering for literati and another for high society members. These gatherings began in 1710, and there were some guests who attended both types. Madame de Lambert's intellectual salon was so well attended it became known as the "antichamber of the Academy" (Chisick, 377), indeed, her endorsement of Montesquieu (1689-1757) was a not insignificant contribution to that philosopher's eventual admittance to the prestigious Académie française.

Madame Marie-Anne de Doublet (1677-1771) hosted a salon in Paris for 40 years. Her salon was known for the presence of women as well as men and the tight bond between attendees, who called themselves "the parishioners" (Chisick, 149). The salon even printed its own journal.

Madame Claudine-Alexandrine Guérin de Tencin (1681-1749), a Parisian by birth and a marquise, was an author in her own right, penning novels and Mémoires du comte de Comminge in 1735. Madame de Tencin had a scandalous life: she fought against her enforced religious vows in 1714, had several lovers but never married, had an illegitimate child (the mathematician Jean Le Rond d'Alembert), procured mistresses for Louis XV of France (r. 1715-1774), and even spent a spell in the Bastille prison after she was charged with extortion by one of her lovers (who then committed suicide). Hosting salons from 1718, Madame de Tencin could pull in stellar guests, but she still called them all the "beasts" of her "menagerie" (Chisick, 410).

Madame Marie de Vichy-Chamrond, Marquise du Deffand (1696-1780), although married, had lived separately at the court of the French regent and then set herself up independently. She established her Parisian salon in 1745 and favoured non-philosophical guests with the sole exception of Voltaire (1694-1778).

Madame Marie Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin (1699-1777), another native Parisian, was, in many ways an apprentice of Madame de Tencin, attending her salons as a young woman. Madame de Geoffrin had the novel idea of hosting two dinners every week, one on Mondays for writers and the other on Wednesdays for artists. She gave money to help her guests who needed it, even buying their paintings. Known for her tact and discretion in manipulating conversation, her salons were noted for their respectability and avoidance of more radical discussions. Madame Geoffrin's daughter, the Marquise de Ferté-Imbault wrote a memoir of her mother's salon activities.

Madame Anne-Catherine Helvétius (neé de Ligniville, 1722-1800) ran the only salon to survive into the years of the French Revolution (1789-1799). Her salon, hosted at Auteuil, then a country retreat outside Paris (but today one of the capital's suburbs), encouraged attendance from poorer members of society and thinkers of different generations. The salon became a great cauldron for political debate with regular attendees including the renowned political theorist the Marquis de Condorcet (1743-1794).

Mademoiselle Julie Jeanne Éléonor de Lespinasse (1732-1776) was the illegitimate daughter of a countess. She became a companion to Madame du Deffand, although she was dismissed when the latter found out that Julie had been holding popular pre-salon meetings with guests who came early for the salon proper. With financial help from Madame de Geoffrin, Julie was able to set up her own salon, and she adopted an entirely different approach by having an open house every day from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m. Only nibbles were provided for guests, but it was popular, nonetheless. The historian and man of letters Jean-François Marmontel (1723-1799), a frequent salon guest, described Julie de Lespinasse in his memoirs as "an astonishing compound of decorum, reason, wisdom, with the liveliest mind, the most ardent soul, and the fieriest imagination since Sappho" (Robertson, 361).

The Guests

Salons were for invited guests only, and if not known personally to the host, a prospective guest usually required letters of introduction from a person who was an acquaintance of the host. Conversation was the main purpose of a salon. A good salon guest had something to bring to this conversation, at the very least wit and elegant French. Those gifted with particular skills were especially appreciated. Writers, painters, musicians, and philosophers were particularly valued by their hosts since they could not only guarantee entertainment for the other guests but also reveal avant-garde trends in their respective fields. There were, too, guests invited for their wealth and social rank as they gave a different sort of prestige to the hostess. Age was no barrier, as shown by the presence of young prodigies like the mathematician Blaise Pascal (1623-1662). Foreigners like the American statesman Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) and the historian Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) were also welcomed at the salons.

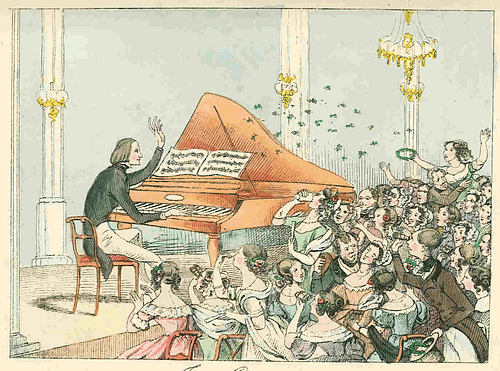

Although salon music was often frowned upon as rather frivolous and certainly not up to the standard of concert performances with an orchestra, some noted musicians, notably Franz Liszt (1811-1886), did do the rounds with personal appearances. Others, like Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880), wrote sentimental ballads and works for the cello and piano specifically for the salons. Some composers hosted their own salons, notably Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868), who, in his retirement, used his hugely popular salons in his grand villa in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris to promote the careers of future stars such as Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) and Georges Bizet 1838-1875).

Liszt, in particular, became such a popular attraction in the salons that his idolisation became known as 'Lisztomania'. Ladies gasped and swooned before this devil of the keyboard, they even scuffled to have possession of the maestro's gloves if he was careless enough to leave them at his piano or if he had tossed them dramatically to the floor, as he often did before he began to play. Liszt fuelled the mania by playing as often as possible and selecting the showiest pieces to play, usually his own music. In this way, Liszt pioneered the recital and helped make soloist performers a staple feature of salon entertainment.

Philosophers who frequented salons included Montesquieu, Voltaire, David Hume (1711-1776), and Adam Smith (1723-1790). Scientists were welcome at the salon, too, especially if they were able to bring along their apparatus and make an entertaining demonstration. The Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) was a frequent guest at salons, a setting he used, like many other intellectuals, to make contacts and further his career.

Writers included Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle (1657-1757) and Horace Walpole (1717-1797). Men of letters often took advantage of reading out extracts from as-yet-unpublished work to gauge the audience's reaction and make revisions when required. Some writers despaired at the fickle patronage on offer, others were downright critical of the intellectual capacity of the aristocratic audience. Voltaire disparagingly wrote in Candide, published in 1759:

The supper was like most suppers in Paris. First, silence; then a cacophonous welter of words that no one can make out; and then jokes, which mostly fall flat, false rumours, false arguments, a smattering of politics, and a quantity of slander.

(Robertson, 362)

The Spread of Salons

Although the precise influence of salons on Enlightenment culture may be debated, the historian H. Chisick notes that salons "provide a rare instance of women playing a dominant role in elite culture" (379). The idea certainly caught on elsewhere soon enough. Elizabeth Montagu (1718-1800) in London hosted a famous salon, which included female authors on the guest list. In Prussia, Henriette Herz (1764-1847) and Rachel Levin organised frequent salons for the Jewish community in Berlin. In Philadelphia, the author Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson (1737-1801) hosted a popular literary salon that pioneered the event in North America. It seems that women everywhere, not only those in Paris, were keen to explore the opportunities of this unique avenue of social and intellectual enrichment.