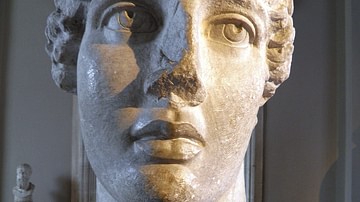

Sappho of Lesbos (l. c. 620-570 BCE) was a lyric poet whose work was so popular in ancient Greece that she was honored in statuary, coinage, and pottery centuries after her death. Little remains of her work, and these fragments suggest she was gay. Her name inspired the terms 'sapphic' and 'lesbian', both referencing female same-sex relationships.

It is possible that she was not gay and the Sappho (pronounced SA-fow) who appears in her works addressing an unnamed female lover is a persona. This does not seem likely, however, as ancient writers, who had access to more of her works than survive today, praised her poetry but criticized her for behaving as a "masculine woman". Very little is known of her life, and of the nine volumes of her work which were widely read in antiquity only 650 lines survive. What is known about her comes from three sources:

- The Suda (10th century CE)

- References by ancient writers

- Her poetry

Later legends claim her works were purposefully destroyed by the medieval church to suppress lesbian love poetry, and although there is evidence that Pope Gregory VII ordered her works burned c. 1073 CE, long before that time many had been lost simply because they were not translated and copied. Sappho wrote in the Aeolic Greek dialect which was difficult for Latin writers, well versed in Attic and Homeric Greek, to translate. They were aware that once there had been a highly-praised female poet from the works of others, and they preserved those poems of Sappho's which others had copied, but they did not translate new ones simply because they did not know her dialect.

Still, her reputation as one of the greatest poets of Greek literature was preserved by others writing about her life who quoted from her works. Some biographies must have been written during her lifetime or shortly after because the outline of her life was known by later writers but, aside from inscriptions such as the Parian Marble (a history of certain events in Greece between 1582-299 BCE) it is not known what these works were.

She was highly praised by Plato (l. 428/427 – 348/347 BCE), who also addressed same-sex relationships in his works and, according to some scholars, drew on Sappho for his own vision of romantic love. In the present day, she is understood as a great gay poet and inspiration to many both within and outside of the LGBTQ community.

Sappho's Life

Sappho was born on the island of Lesbos, Greece, to an aristocratic family. While scholars regularly claim that her wealth allowed her to live a life of her own choosing, this cannot be supported. Most women in ancient Greece married according to the traditions and customs of their city-states, and Sappho's wealth would not have made her immune to the expectations of her family and society. Most likely, she was able to live as she pleased because of the high esteem in which women were held on Lesbos and Sappho's own unique personality. The historian Wendy Slatkin writes:

Considering the severe restrictions on women's lives, their inability to move freely in society, conduct business, or acquire any type of non-domestic training, it is not surprising to find that no names of important [female] artists have come down to us from the classical era. Only the poet Sappho received high praise from the Greeks; Plato referred to her as the twelfth Muse. Significantly, she came not from Athens or Sparta but from Lesbos, an island whose culture incorporated a high regard for women. (42)

Slatkin’s reference to Plato calling Sappho "the twelfth muse" (usually given by scholars as "the tenth muse") alludes to his alleged praise of her as belonging in the company of the Nine Muses who inspired art, music, dance, and poetry. There is no evidence Plato actually made this statement, and it is thought to be a creation of later writers, attributed to Plato. Even so, the fact that this phrase exists highlights Sappho’s enduring reputation as a poet.

She is said to have operated a school for girls on Lesbos, but this seems to be a later invention of the 19th century CE which confused her with her protégée Damophila who ran a girl's school in Pamphylia. Still, it is probable she did run a girl’s school and passed that legacy down to her student. Wealthy parents are said to have sent their daughters to study eloquence with Sappho to elevate them as prospects for marriage.

Most details of her life have been lost, but it is known she was raised learning to play the lyre and came to compose songs, may have been married to a man at some point who died, may have had a daughter named Cleis (named after Sappho's mother), had three brothers, Erigyius, Charaxus, and Larichus, the latter two addressed in her poetry. She came from a well-to-do family who were most likely vintners or involved in wine export from Lesbos and is said to have been exiled twice to Sicily because of her political views. She was famous enough to have statues raised and ceramics fashioned in her honor, and, later, coins minted with her name and image on them. Historian Vicki Leon comments:

Mytilene, the capital of Lesbos, proudly issued Sappho coins; some have been found that date to the third century A.D. - nine hundred years after the poet's death. Sappho (or, rather, her fame) cornered the ancient equivalent of the T-shirt concession too: her portrait and name appear on vases, bronzes, and, later, much Roman art. (151)

She is described in ancient texts as being short in stature and dark in complexion. A romantic interest in women is evident from her poetry but most scholars advise against reading her works biographically. In the same way that poets through the ages have written works expressing a persona not their own, so too could Sappho have composed her poems.

The intimacy and depth of feeling would seem to suggest that Sappho was lesbian but that does not mean she was. Homer's description of Greek warfare and the dust and blood before Troy does not mean he was a participant in the battle; only that he was a great poet. As there was no distinction between homosexual and heterosexual relationships in ancient Greece (or elsewhere, as the terms are a modern-day invention), it is likely that Sappho addressed a wide range of topics and had no reason to exclude her characters’ sexual orientation any more than she would any aspect of an individual. The scholar Sir Richard Livingstone comments:

Greek simplicity recalls us to the central interests of the human heart. Greek truthfulness is a challenge to see the world as it is and shun the emptiness of mere music, the falsities of rhetoric or sentiment, the incompleteness of writers who, instead of seeing life as a whole, ignore or emphasize a part of it as their own sympathies dictate. (286)

While it is possible, then, that Sappho was a lesbian, it is equally possible that she wrote on many subjects but that her works expressing lesbian love are the ones that have survived most intact. These were possibly her most popular as they addressed romantic love, a subject as popular among audiences in ancient Greece as it is today.

Sappho’s Sexuality

It is generally accepted that Sappho was a gay poet whose work became so popular that, by the late 6th century BCE, the meaning of the term lesbian has changed from "one from Lesbos" to "a woman who prefers her own sex". The Greek lyric poet Anacreon (l. c. 582 - c. 485 BCE), writing after Sappho, alludes to women of Lesbos as lesbians in the modern-day sense of the term. In the following verse, the speaker warns a suitor away from a girl who has no interest in men:

Not that girl – she’s the other kind,

One from Lesbos. Disdainfully,

Nose turned up at my silver hair,

She makes eyes at the ladies. (Salisbury, 316)

In Plato’s dialogue of the Phaedrus, Socrates praises both Sappho and Anacreon as authorities on love referring to them as "Sappho the lovely and Anacreon the wise" (235c). Scholar E. E. Pender notes, "the reason why Plato pays tribute to Sappho and Anacreon is that they have captured and expressed so vividly the shock of love" (1). That Sappho herself, not a persona, is expressing romantic feelings for a woman is supported by later writers who reference Lesbos as Anacreon does after Sappho’s fame was established.

Even so, and although she is regularly referenced as a gay poet in the modern day, there is no definitive text positively identifying her as such. Claiming she was gay based on her lyrics is the same as someone today claiming Bruce Springsteen was a blue-collar worker based on his songs. The best one can say is that she was most likely gay and became famous for articulating the experience of love anyone, of whatever sexual orientation, had felt.

Scholars Mary R. Lefkowitz and Maureen B. Fant note that "Many of [Sappho’s] poems describe a world that men never saw: the deep love women could feel for one another in a society that kept the sexes apart" (2). Along these lines, Sappho’s ability to so perfectly express lesbian love in her work argues for lesbian sexual orientation though, again, this cannot be claimed with certainty.

Sappho's Poetry

Her surviving works are deeply personal reflections on desire, love, and loss. Livingstone writes:

In life, human beings return from a distracting variety of interests to a few simple things; or, if they do not return, run the risk of losing their souls. In literature, which is the shadow of life, they need to do the same. (259)

Sappho seems to have understood this clearly and focused her work on the most basic and most enduring human emotions. Scholar Suzanne MacAlister comments:

Sappho is the first extant Greek poet to write expressly about the feeling generated by love. The best example of this is found in what is perhaps Sappho’s most famous fragment – phainetai moi – which also stands apart from surviving love poetry written by men in that it talks about the physical manifestation of emotion. The physical manifestation of love in Sappho’s lyrics is not expressed as sexual. There is next to nothing in any of her fragments that mentions any sexual act between women. (Aldrich & Wotherspoon, 392)

Sappho, instead, focuses on what the speaker in the poem is feeling, the rush of excitement at falling in love. The original titles of her works, except her Ode to Aphrodite, have been lost and today the fragments are known either by numbers (which vary according to translations) or the first line, as in Phainetai Moi (“He seems to me”) in which the speaker expresses her feelings while watching a couple, perhaps at a banquet, and addresses these feelings toward the woman:

He seems to me to be the equal to the gods –

Whoever sits opposite you

And listens to you

Talking sweetly

And laughing desirably, which makes

The heart in my breast fly.

For whenever I look upon you for an instant

I can no longer find a single word,

But my tongue is broken, and instantly

Delicate fire runs beneath my skin,

And I see nothing with my eyes, my

Heart pounds

A cold sweat covers me, trembling

Grabs my all, I am paler than grass,

And I think I am little short

Of dying.

But everything can be ventured.(Plant, 14-15)

The last line is also given as "everything can be endured", changing the meaning of the poem from the speaker wanting to pursue a relationship (ventured) to her having to endure her feelings without being able to express them to the beloved.

The simplicity of construction in her work concentrates the reader's attention on the emotional moment itself and, like all great poetry, creates an experience which is easily recognizable. Another famous example of this is her poem, "I Have Not Had One Word from Her" also sometimes titled Parting. The poem is thought to have been written by Sappho to her lover who was a courtesan and may have been forced to part from her due to her occupation when she was hired by a client and had to move:

I have not had one word from her

Frankly I wish I were dead

When she left, she wepta great deal: she said to me, "This parting must be

endured, Sappho. I go unwillingly."I said, "Go, and be happy

but remember (you know

well) whom you leave shackled by loveIf you forget me, think

of our gifts to Aphrodite

and all the loveliness that we sharedall the violet tiaras,

braided rosebuds, dill and

crocus twined around your young neckmyrrh poured on your head

and on soft mats girls with

all that they most wished for beside themwhile no voices chanted

choruses without ours,

no woodlot bloomed in spring without song."(Barnard Translation, Sappho, 1)

The intimacy of this poem is characteristic of all Sappho's surviving work. She was not only a brilliantly honest poet, however, but also a virtuoso of technique. She invented a completely new meter for poetry, now known as Sapphic Meter or the Sapphic Stanza which consists of three lines of eleven beats and a concluding line of five. The following poem, known by its first line but also as Please, is an example of this (although the present translation does not preserve the steady eleven beats of the first three lines of each stanza):

Come back to me, Gongyla, here tonight,

You, my rose, with your Lydian lyre.

There hovers forever around you delight:

A beauty desired.Even your garment plunders my eyes.

I am enchanted: I who once

Complained to the Cyprus-born goddess,

Whom I now beseechNever to let this lose me grace

But rather bring you back to me:

Amongst all mortal women the one

I most wish to see.(Roche Translation, Sappho, 1)

Not all of her poetry praised her beloved, however, as fragment 32 makes clear: "I never found any woman more annoying, Irana, than you…" (Plant, 18). Most, though, are intimate confessions of love, including her Ode to Aphrodite, the only complete poem extant, in which she begs the goddess of love to help her win the affections of a young woman.

Her poetry would have been sung to the accompaniment of the lyre (which is how lyric poetry gets its name) and performed publicly at events and private dinners. A famous story related by Stobaeus (l. 5th century CE), who collected such ancient anecdotes, writes:

Solon of Athens heard his nephew sing a song of Sappho's over the wine and, since he liked the song so much, he asked the boy to teach it to him. When someone asked him why, he said: 'So that I may learn it, then die'." (Florilegium 3.29.58)

Whether the story is true is not as important as what it says about Sappho's poetry. Solon was considered one of the wisest men who ever lived and was counted among the Seven Sages of Greece. He was known for teaching the precept "moderation in everything" and so for him to react so emotionally in this anecdote to Sappho's song is significant in that one so famous for his wisdom could be so deeply moved that he would desire nothing more after learning the song.

Conclusion

The manner of Sappho's death is unknown. The Greek comedy playwright Menander (l. c. 341-329 BCE) started the legend that she committed suicide by leaping from the Leucadian cliffs over the unrequited love of a beautiful ferryman named Phaon:

...they say that Sappho was the first,

hunting down the proud Phaon,

to throw herself, in her goading desire, from the rock

that shines from afar. (Fragment 258 K, of Leukadia)

This seems highly unlikely and has been rejected by historians in the present day and as far back as the Greek writer Strabo (l. c. 64 BCE - 24 CE). The Leucadian cliff (also known as Cape Leukas on the island of Lefkada) was a famous "lover's leap" following a story in which Aphrodite flung herself into the sea while mourning the dead Adonis. Menander could have been simply making fun of romantic love by having a woman known for her lesbian love poetry kill herself over a man.

Interestingly, Artemisia I of Caria (c. 480 BCE), another strong woman of note, was also said to have committed suicide by throwing herself into the sea and, according to some sources, from the same spot. Artemisia's suicide story has also been discredited. Sappho seems to have lived into old age and died of natural causes but this, like most of the events of her life, is far from certain.

What is clear is that she was a poet of immense talent whose work made her famous. Her poetry was so popular, according to Leon, that,

Not only was her work sung, taught, and quoted - but the very phrases she coined, from 'love, that loosener of limbs' to 'more golden than gold', entered the Greek language and were used so much they eventually became clichés. (150)

She was a much sought-after performer and her compositions continued to be sung and admired long after her death. Sappho understood her poetry as her legacy as one of her most oft-quoted fragments suggests: "Someone, I tell you, will remember us, even in another time" (Fragment 77, Plant, 24). She referred to her poetry as her "immortal daughters" and so they continue to be as readers 2,000 years after their creation continue to respond to them with the same enthusiasm they inspired when they were first written.