The Ancient Greek symposium is often considered an important part of Greek culture, a place where the elite drank, feasted and indulged in sometimes decadent activities. Although such practices were present in symposia, the writing and performance of poetry is perhaps the most interesting and thought-provoking element of the ancient sympotic tradition.

This essay aims to investigate the interestingly varied relationship between the symposium and poetry by approaching it on a number of different levels: the first exploring poetry's capability to inform its reader about the symposium and its associated practises; the second probing poetic relationships with and similarities to other key sympotic components, such as wine; the third questioning the suitability of poetry as a source for establishing the nature of such a relationship.

From a modern perspective, that the symposium was a context for the performance of literature immediately and incontrovertibly implies a connection between poetry and the symposium. This then raises questions of the nature of said relationship: did poetry simply sing of sympotic activity, opening up the exclusive and elusive world of the Ancient Greek elite? How was the environment of the symposium particularly suited to the performance of poetry, and did this setting determine or in any way influence the kind of poetry performed?

Xenophanes, a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and critic, provides a splendid account of sympotic customs, noting the setup of the wine mixing bowl, the food available, and the prayers and libations to the deities before proceedings begin, insinuating that there was a heavily ritualised character to the symposium. In addition, though writing almost a century earlier, Alcaeus, a Greek lyric poet, wrote the line, 'from Teian cups the wine drops fly,' which indicates the playing of drinking games of sorts. It is interesting to note the different times within which each poem was written; the large chronological gap between the two shows that the tradition of depicting sympotic events in poetry was not only maintained, but important.

Although in many cases, as examined above, sympotic poetry seemingly provides descriptions and depictions of activities and events during the symposium, it has been argued that pictures of moderate drinking parties may not necessarily mirror reality but are rather a guide as to how to drink 'properly'. Considering also that the symposium was considered a centre for the transmission of traditional values, it seems logical that poetry should reflect not only the happenings but also the aims and intentions of the symposium.

For example, Anacreon, writing in the 6th century BCE, provides not only guidance regarding the proper ratio of mixing water to wine: 'come boy, bring us a bowl so I can drink a sconce. Pour in ten ladlesful of water, five of wine, so I can bacchanize once more with no disgrace,' but he also advises on the manner in which one should consume wine, ' come now, this time let's drink not in this Scythian style with din and uproar, but sip to the sound of decent songs.' In addition, Alcaeus, a poet from around the 7th-6th centuries BCE, warns of the dangers of wine, 'if wine fetters the wits, often he hangs his head and blames himself, regretting what he's said, but its too late to take it back.'

The occurrence of such guiding themes in poetry written almost 100 years apart emphasizes their importance and hints that such a relationship between the symposium and poetry was strong and continuous.

These three instances demonstrate this poetic role and highlight a mutual exchange between the symposium and poetry; while the symposium may provide the subject matter, poetry can provide the constraints and guidance for such subject matter. This shows that already, although only following a brief investigation, the relationship between poetry and the symposium is more intricate than meets the eye.

It has been established that a key aspect of the relationship between the symposium and poetry is poetry's ability to depict sympotic activities - the 'seen' components of the symposium, so to speak. However, the relationship assumes a new dimension when one considers the portrayal of the 'invisible' sympotic atmosphere through, rather than imagery and words, the very nature of sympotic poetry. The symposium as an exclusive gathering of elites implies an intimate and sheltered environment for the recitation of poetry.

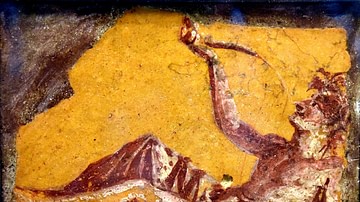

Pottery carrying depictions of the symposium show a keen focus on internal events amongst the participants, and an inward facing layout is suggested by Xenophanes, who points out 'the altar in the middle bedecked with flowers', which gives rise to the idea that the symposium was a gathering separate from the outside world. The repetition of this imagery in different kinds of sources lends strength and credibility to the case for an inwardly directed symposium. From here, parallels can be drawn between sympotic poetry and the arena in which it was performed for and written in.

Exemplifying the notion of sympotic isolation, it has been suggested that Theognis, a sixth century BCE Greek lyric poet, saw the themes of sympotic poetry and the symposium as providing refuge from the corruption of Megara, which supports the idea of the sympotic environment as being very sheltered from the outside world. Similarly, although in a slightly lighter-hearted manner, Alcaeus shows the symposium to be an escape from the outside world, but in this case from the weather, 'defeat the weather; light a fire, mix the sweet wine unstintingly and put a nice soft cushion by my head.' Furthermore, although the earliest sympotic poetry may have actually been contemporary with early epic, the content of the respective genres varies widely, due in part perhaps to the different performance environments and audiences of each genre?

Having investigated the more straightforward features of the relationship between the symposium and poetry, the time has come to direct attention to its more subtle and elusive constituents. Possibly the most interesting fact about this increasingly intricate relationship, is that poetry finds itself not only associated with the symposium as a whole, but linked in a labyrinthine manner to key elements within the symposium itself, such as wine. In other words, the connections between poetry and the symposium represent relationships within a relationship.

It hardly needs to be said that wine was a key component of the symposium. What is curious is the way in which the characteristics of wine and poetry are closely related and in some cases interwoven. On the one hand, one could almost go so far as to argue that, poetry is the literary compliment of wine, and that in the context of the ancient symposium, poetry was approached in a manner not so far removed from the way in which wine was viewed. However, on the other, it could be claimed that poetry was the sympotic antithesis of wine, revealing a more complicated relationship between poetry and wine than may have previously been appreciated.

It is evident that many characteristics of wine and poetry are intimately linked in the symposium. Alcaeus remarks that 'wine puts cares out of mind,' and that 'wine is a window into a man' properties shared also with poetry, especially that within the sympotic context which played upon particularly pleasurable themes, as aforementioned. Although parallels between the effects of wine and poetry have begun to emerge, this is not to say that wine and poetry work in the same way. Parallels can also be drawn, establishing a relationship, between wine and the composition of poetry. The historian Whitmarsh states that solids and liquids are not the same as food and drink, which require artfulness and cultivation.

It is well established that wine was very much a cultivated and refined product, having been brought from outside into the home, drawing many parallels to the god Dionysos, a key player in the symposium. The writing and 'cultivation' of poetry by the author seems to reflect closely the winemaking process. Additionally, the heavily ritualised and controlled practice of mixing water with wine, mentioned previously in Anacreon's verse, can be interpreted as a mirroring of the careful art of fitting words into a regularly repeated meter then singing them to a tune of a similarly repetitive nature to the meter. Thus it is not unreasonable to suggest that poetry could in fact masquerade as the literary equivalent of wine.

Despite the appearance of a harmonious and close relationship between poetry and wine, it can be seen that while poetry may hypothetically offer itself as the literary equivalent of wine in the symposium context, it can simultaneously act as a literary antithesis to wine, almost as a sympotic antidote. The fact that poetry and wine share similar capabilities, as expressed above, raises the question of whether poetry could be interpreted as a medium providing all the benefits of wine, yet without the risk of social embarrassment.

The usefulness of ancient poetry as a source for studying the symposium cannot and should not be denied. However, it is important not to let this usefulness get in the way when trying to establish the relationship between the symposium and poetry, as the modern perspective of the relationship could cloud the ancient relationship. On the one hand, as shown above, poetry has a great deal to tell the reader, both implicitly and explicitly about the ancient symposium, demonstrating that it is a good source for establishing the relationship between the symposium and poetry.

Yet on the other hand, the fact that a relationship can be seen between poetry and the symposium without much in-depth investigation into the matter raises the question of whether it would be better to consider other sources, such as pottery for example, so as to gain a wider and clearer perspective on the relationship. Lastly, it is interesting to ask why poetry is considered such a suitable source for establishing the relationship between the symposium and poetry; is it because, like the symposium, poetry was a key element of Greek culture which endured through time, therefore, the modern scholar is keen to link the two together in the aim of figuring out their method of survival?

The relationship between poetry and the symposium was complex, increasingly so the deeper into individual sympotic elements one delves, finding more subtle connections and similarities all the time. There was also almost certainly a degree of mutual exchange between the two, with one influencing and inspiring the other and vice versa.

One thing in particular stands out; that interpretations of the relationship between poetry and the symposium will continue to change and evolve over time, in much the same way that poetry and the symposium can be seen to have helped one another develop in the ancient world. The fact that an active relationship between two aspects of Ancient Greek culture can still be seen today is very exciting.