Satyrs (aka silens) are figures from Greek mythology who were followers of the god of wine Dionysos. Satyrs were often guilty of excessive sexual desires and overindulgence of wine. Men with a horse's tail and ears or men with goat legs, these shaggy and unruly creatures lived wild in the forests and symbolised the dangers of unrestraint.

Satyrs are frequently depicted in ancient art, typically causing havoc by attacking women and performing lewd tricks with wine cups. They could be more industrious when Dionysos put them to work making wine. The most famous individual satyr is wise old Silenus, who was the tutor of Dionysos. A specific genre of Greek theatre was the satyr play which involved actors dressing up as satyrs and where there was an entire chorus of satyrs.

Wild Men of Excess

The name 'satyr' was used in the Peloponnese of ancient Greece while 'silen' was used in Attica. At some point in the 6th century BCE, the names came to be used interchangeably in Greek literature and in labels on Greek pottery.

Satyrs often appear in Greek myths as lustful and wine-loving wild men of nature who had some animal features. Intelligent yet mischievous, lewd yet skilled in music, the physique of the satyrs reflects their seemingly conflicting personality traits. Early depictions of satyrs show them as men with a horse's tail and ears while later versions are half-man and half-goat, sometimes with entire goat legs or just hoofed feet. The elements of goat may reflect a later association with the pastoral god Pan, also thought to inhabit forest areas. Satyrs often have snubbed noses, wild-looking hair, and long beards. A weapon of the satyr was the thyrsus, a staff entwined with ivy and topped with a pine cone. These forest dwellers were frequent companions or followers of Dionysos, the Greek god of wine and merriment, and made up his thiasos or troupe, which included nymphs and maenads.

The cult to Dionysos involved orgiastic rituals where the participants - both men and women - were taken over by a Dionysian frenzy of dancing and merriment to such a degree that they transcended themselves. The satyrs came to represent the more excessive side of the Dionysos cult. With their demonic energy, satyrs spent their time chasing and sometimes raping animals or they were employed by their master in wine-making. Consequently, with their transformation of nature into manufactured products, the satyrs bridge the gap between wild abandon and the creation of ordered culture.

Satyrs had a connection with several major festivals in the Greek religion. People dressed as satyrs for processions like the Anthesteria of Athens (a festival which honoured Dionysos and the drinking of new wine), in Alexandria in the Hellenistic period, and in Rome. Satyrs were involved in secret initiation ceremonies for some Greek cults, particularly those involving a connection with the next life and funerary rituals.

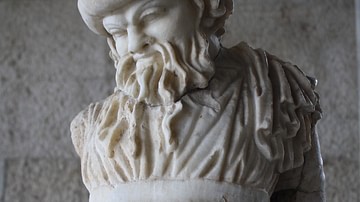

Silenus the Satyr

The satyr Silenus (or Silenos) was considered the father of all the other Greek satyrs and, famed for his great wisdom, he was the wise tutor of Dionysos and so was another bridge between the wisdom of nature and the intelligence of humanity. Silenus was once captured by King Midas, ruler of Phrygia in Asia Minor who was famous for his wealth. In one version of the myth, Midas merely found Silenus in his rose garden one morning suffering from the excesses of the night before. In an alternative version, Midas purposely set a trap for the satyr so that he could gain some of his fabled knowledge. Whether by luck or design, Silenus did spend five days and five nights with his host when he told him all manner of strange tales of faraway places. Midas then returned Silenus to Dionysos and, in gratitude, the god granted the king a wish. This was how he came to have his ‘Midas touch’ where everything he touched turned to solid gold. When he could not eat or drink, Midas pleaded with Dionysos to reverse his new talent and this he did by telling the greedy king to wash in the source of the Pactolus in Lydia.

Marsyas the Satyr

The great Greek god Apollo, who was believed to be the master of the lyre, defeated the Phrygian satyr Marsyas and his double flute or aulos in a musical competition judged by the Muses. Marsyas was then flayed alive for his impudence while the location of his defeat was the Marsyas River in Phrygia, a tributary of the Maeander River. According to Robert Graves, the specialist in Greek myths, this myth of a musical competition may have a deeper meaning:

Apollo’s victories over Marsyas and Pan commemorate the Hellenic conquests of Phrygia and Arcadia, and the consequent supersession in those regions of wind instruments by stringed ones, except among peasantry. (81)

How Are Satyrs Represented in Art?

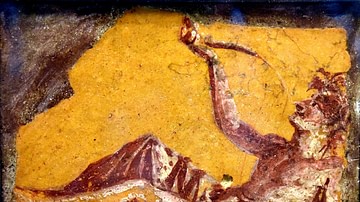

Representations of Dionysos in Greek Archaic and Classical art frequently show him in the company of satyrs. Typically, Greek satyrs are portrayed naked with long hair, a long beard, a long tail like a horse, and are ithyphallic. Sometimes these horse-like satyrs have hairy bodies and their whole legs are animal as on the celebrated Francois Vase, a 6th-century BCE Attic volute-krater found in Chiusi and now in the Archaeological Museum of Florence. They are often dancing, cavorting, and generally causing a disturbance as peripheral figures in scenes showing Dionysos, other gods, at weddings and similar community celebrations. Other common scenes include a guard of satyrs escorting Hephaestus back to Mount Olympus to free the captive Hera, and fighting giants in sculptural Gigantomachies.

Satyrs making wine frequently appear in scenes on Greek pottery, crushing the grapes with their feet in large vats, pouring the wine into storage vessels, balancing cups on unusual parts of their body, and often drinking plenty as they work. A fine example of this type of scene is a 5th-century BCE black-figure belly amphora now in the Antikenmuseum of Basel. There are also some unexplained scenes on pottery, the significance of which has been lost such as satyrs torturing a woman tied to a tree on a lekythos now in the National Museum in Athens. Satyrs sometimes attack a tomb or religious monument and sometimes sneak up on Hercules to steal his weapons, perhaps a reference to a now lost satyr play. Actors wearing the costume of a satyr and doing everyday tasks like sport or in family scenes appear on many 5th-century BCE pottery vases.

The capture of the satyr Silenus by King Midas is captured in a number of scenes on Greek pottery from c. 560 BCE. A 6th-century BCE Attic black-figure vase from Aegina shows two men escorting the satyr after having captured him using rope and a wineskin (Altes Museum, Berlin).

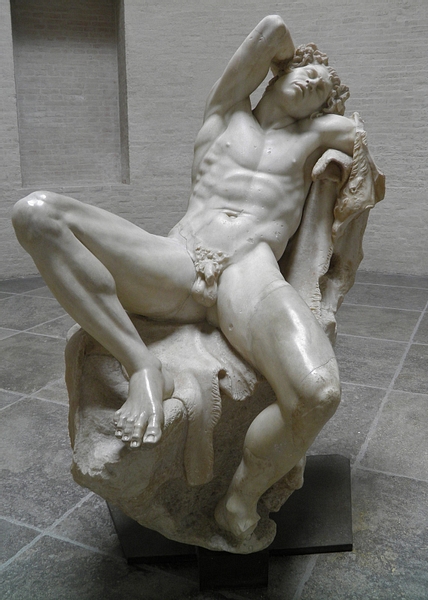

The unfortunate Marsyas appears in sculpture, often as a striking figure with his hands tied high above his head while he is dealt his terrible punishment. A fine example is an early imperial Roman sculpture, which copies an earlier Greek original. It is now in the Capitoline Museums of Rome.

What is a Satyr Play?

Satyr plays were an important element of Greek theatre from the end of the 6th century BCE. The most famous competition for the performance of Greek tragedy was a part of the spring festival of Dionysos Eleuthereus or the City Dionysia in Athens. Each festival, famed tragedians like Aeschylus (c. 525 - c. 456 BCE), Sophocles (c. 496 - c. 406 BCE), and Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE), submitted a trio of tragedy plays and one satyr play.

There was a strong connection between Greek drama and Dionysos. It is believed that theatre sprang from the orgiastic rituals of wine, Greek dance, and song as, like Dionysos' worshippers, actors strove to leave behind their own persona and become one with the character they were playing. Indeed, priests of Dionysos were given seats of honour in Greek theatres.

The short satyr play, specifically, had actors dressed as satyrs with a mask, hairy body, and a pair of shorts with a horse tail behind and a false erect phallus in front. The satyrs could be important characters in the play, and the chorus was composed entirely of them. The subject of these plays was typically a parody of a well-known myth. Satyr plays were more sober than a comedy play but not as highbrow as a tragedy. Unfortunately, only one complete satyr play survives, the Cyclops by Euripides, which has 709 lines. Many fragments do survive of other satyr plays, the most substantial being about half of Ichneutae (the ‘Trackers’) by Sophocles. These pieces show that the satyrs took centre stage in the plays, and there were many scenes involving their skills at wine-making, acrobatics, and making mischief for the more heroic central characters like Hercules or Odysseus. Although satyr plays were no longer part of Greek theatre competitions from the 4th century BCE, they did continue to be performed in isolation right into the Roman period.