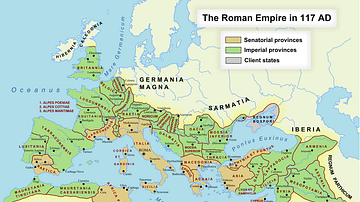

The Western Roman Empire is the modern-day term for the western half of the Roman Empire after it was divided in two by the emperor Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE) in c. 285/286 CE. The Romans themselves did not use this term. At its height (c. 117 CE), the Roman Empire stretched from Italy through Europe to the British Isles, across North Africa, down through Egypt and up into Mesopotamia and across Anatolia. By 285 CE the Roman Empire had grown so vast that it was no longer feasible to govern all the provinces from the central seat of Rome.

Soon after coming to power, Diocletian made a fellow-officer named Maximian (r. 285/286-305 CE) his co-emperor and, in doing so, divided the empire into halves with the Eastern Empire's capital at Byzantium (later Constantinople) and the Western Empire governed from Milan (with Rome as a “ceremonial” or symbolic capital). Both halves were known as 'The Roman Empire' although, in time, the Eastern Empire would adopt Greek instead of Latin as its official language and would lose much of the character of the traditional Roman Empire.

The Eastern Empire flourished while the Western Empire struggled and finally fell c. 476 CE. In time, it became the foundation of the Holy Roman Empire (962-1806 CE) - seen as a revival of the values and order of the Roman Empire at its height - first under the reign of Charlemagne (r. 800-814 CE) whose successors could not maintain it, and then officially founded by Otto I of Germany (r. 962-973 CE). The Holy Roman Empire steadily lost cohesion and authority as an outmoded institution incapable of governing in a modern age, becoming increasingly corrupt and ineffectual, until it was finally dissolved in 1806 CE.

Rome & Crisis

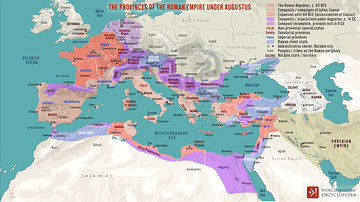

The Roman Empire was founded by the first emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE-14 CE) and steadily grew in power through the reigns of the Five Good Emperors, so called because of the prosperity and order they maintained. The Five Good Emperors were:

- Nerva (r. 96-98 CE)

- Trajan (r. 98-117 CE)

- Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE)

- Antoninus Pius (r. 138-161 CE)

- Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE)

After Marcus Aurelius, his son Commodus (r. 180-192 CE) became emperor and dissipated Rome's power through self-indulgent and inefficient rule. After Commodus was assassinated, Rome experienced a year of confusion (known as The Year of the Five Emperors) during which five different men took power and were deposed until Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE) founded the Severan Dynasty and restored order. Severus courted the favor of the military, having learned from The Year of the Five Emperors that this was in an emperor's best interest, and debased the currency in order to be able to generate more money to raise the salary of the troops. He further established the precedent of the emperor relying heavily on the support of the military, thus effectively compromising the traditional role of Roman emperor.

In 235 CE, the emperor Alexander Severus (r. 222-235 CE) was assassinated by his own troops who felt he was not acting in their best interests. This plunged Rome into the era known as the Crisis of the Third Century (also the Imperial Crisis, 235-284 CE) during which 20 emperors would come and go in almost 50 years, a startling statistic when compared with the 26 emperors who ruled in the 250 years between Augustus and Alexander Severus.

When Diocletian came to power, he restored order and divided the empire's rule between himself in the east and Maximian in the west. The Crisis of the Third Century had shown how perilous it was to have Rome dependent on a single emperor whose death could result in instability, and Diocletian also understood that the empire was simply too large for one man to govern effectively. After the division, Diocletian instituted his tetrarchy – rule of four – whereby the empire was further divided between four men who ruled their own distinct sections.

Under the reign of Constantine the Great (324-337 CE), the empire as a whole flourished but it was never as cohesive as it had been under the Five Good Emperors. The Eastern Empire established lucrative trade and prospered while the Western Empire struggled and, since the two sections tended to view the other as competition, they worked as separate entities who shared a common bond but served their own interests.

The Dissolution of the Empire

Even so, the two halves of the empire continued to prosper equally until the reign of the Emperor Theodosius I (379-395 CE) when internal and external forces exerted themselves to break the two halves apart. These forces included, but were not limited to:

- Political instability

- The self-interest of the two halves

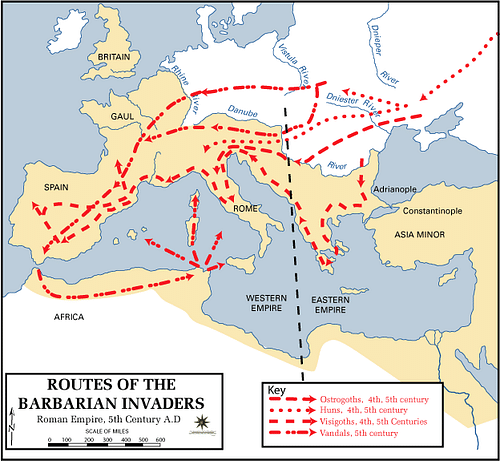

- Invasion of barbarian tribes

- Government corruption

- Mercenary armies

- Over-reliance on slave labor

- Massive unemployment and inflation

- The rise of Christianity

As noted, Eastern and Western Rome pursued their own interests instead of working in concert toward shared goals. This lack of cohesion fostered political instability which was made worse by government corruption, especially among provincial authorities who abused their positions for personal gain. The Goth and Hun mercenaries in the Roman army owed no allegiance to Rome, they were just fighting for pay and, further, were not treated as well as they felt they deserved. The over-reliance on slave labor took jobs away from the lower classes who then relied on public assistance and the earlier debasement of the currency under Septimus Severus had become a policy of later emperors, resulting in inflation.

Theodosius I's zeal in spreading Christianity and crushing pagan influences has also been noted as a contributing cause to the fall of Rome. The earlier pagan belief system of the Romans had been a state religion; the faith informed the state, and the state supported the faith. The Roman gods were concerned with Rome and its success; the new Christian god had no vested interest in Rome per se and was the god of everyone. The nature of Christianity, according to some scholars, served to weaken the traditional cohesion Roman paganism provided to the empire. That point has been debated for centuries but Theodosius I's persecution of the pagans is a far more certain factor since, as emperor of both the east and the west, he had the power to unite the Roman Empire but, instead, divided it further through religious intolerance.

Theodosius I came to power following a number of serious setbacks for Rome. The Gothic War of 376-382 CE severely weakened the Western Empire even though the battles were routinely fought by forces from the Eastern Empire. At the Battle of Adrianople in 378 CE, the Eastern Emperor Valens (r. 364-378 CE) was defeated by Fritigern (d. c. 380 CE) of the Goths and many historians agree that this marks the beginning of the end of the Roman Empire. The emperor Gratian (of the Western Empire, r. 367-383 CE) had elevated Theodosius to co-emperor status and, when he died, Theodosius I became emperor of both halves of the empire. Theodosius I's treatment of the mercenary Goths – especially at the Battle of the Frigidus in 394 CE – provoked the Goth king Alaric I (r. 395-410 CE) to sack Rome in 410 CE.

This is not at all to claim that Theodosius I's reign led to the end of the Western Roman Empire. There is no single cause for the decline and fall of Rome. A steady deterioration in power and prestige had been ongoing prior to the Roman defeat at Adrianople and all these challenges and pressures culminated in the deposition of the emperor Romulus Augustulus (r. 475-476 CE) by the Germanic king Odoacer on 4 September 476 CE, prior to Adrianople. The Western Roman Empire, essentially, fell with the rise of Odoacer who ushered in a new era which would see the Kingdom of Italy replace the power of Rome in the west.

The Kingdom of Italy

While c. 476 CE is the traditionally accepted date for the end of the Western Roman Empire, that entity did continue on under the rule of Odoacer (r. 476-493 CE) who, officially anyway, was simply ruling in place of the deposed emperor Julius Nepos (who had been deposed by the general Orestes who had placed his son, Romulus Augustulus, on the throne). Therefore, there are historians and scholars who date the end of the Roman Empire to the assassination of Julius Nepos in 480 CE. After Nepos' death, Odoacer annexed the region of Dalmatia to his own lands which concerned the emperor of the eastern part of the empire, Zeno (r. 474-475, 476-491 CE), by whose authority Odoacer had been allowed to rule. In Zeno's view, Odoacer was acting with too much independent authority and was beginning to pose a significant threat.

His suspicions were confirmed when Odoacer was found to be backing Zeno's rival, the general Illus, in a revolt. Zeno employed the Gothic leader Theodoric (later known as Theodoric the Great, r. 493-526 CE) to defeat Illus but then Theodoric turned his formidable army on Zeno and Constantinople. Scholar Guy Halsall explains:

The Goths threatened Constantinople and ravaged the Balkans but could not take the capital, whilst Zeno, secure behind the city's famous triple line of walls, was unlikely to drive the latter completely from his territories. A solution was required, agreeable to both parties, and found: for Theodoric's Ostrogoths to move to Italy and dispose of the 'tyrant' Odoacer. (287)

Theodoric invaded Italy at the head of his army in 488 CE and battled the forces of Odoacer across the region for the next four years. A compromise was finally brokered by John, Bishop of Ravenna, by which Odoacer and Theodoric would jointly rule but, at the feast to celebrate the end of hostilities in 493 CE, Theodoric assassinated Odoacer and claimed the kingship for himself.

Theodoric's reign brought order and prosperity to the region in the form of laws, building projects, and increased food production but, after his death in 526 CE, his successors could not hold the kingdom together as well. The Eastern emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) asserted his control over the Kingdom of Italy and met the greatest resistance from the Ostrogoth king Totila (r. 541-552 CE) who claimed the right to the same autonomy Theodoric had won from Rome. Justinian I sent the famous general Belisarius (l. 505-565 CE) to Italy but even he could not outsmart or outfight Totila. The general Narses (l. 480-573 CE) finally defeated Totila at the Battle of Taginae in 552 CE, returning Italy to Roman authorities until the invasion of the Lombards in 568 CE.

The Holy Roman Empire

The Lombards grew in power, establishing dukedoms throughout Italy until they were defeated in 774 CE by Charlemagne at the Battle of Desiderius. By this time, most Lombards had assimilated with the people of Italy and the neighboring Franks and Charlemagne's victory simply accelerated this process. Christianity was now the dominant religion of Europe and, since it had been legitimized and spread under Roman rule, there were many Christians who refused to let the concept of the Roman Empire disappear. Charlemagne of the Franks was proclaimed Western Roman Emperor in 800 CE by Pope Leo III and entrusted with protecting and perpetuating the Christian message.

Charlemagne became the preeminent Christian champion of his time, extending his empire while at the same time launching crusades against the Muslim Saracens as he had previously done against the pagan Saxons (through the Saxon Wars of 772-804 CE). Many tales and poems, including the famous Chanson de Roland (the Song of Roland), were written praising Charlemagne and his knights for their chivalrous adventures defending Christian values at the cost of Christian and non-Christian lives. This new Christian empire claimed to be the direct descendant of the old Roman Empire only championing the cause of Christ instead of that of an individual emperor.

Charlemagne set the foundation for the new empire but, as with many powerful and effective rulers, his successors could not maintain his same level of efficiency and the realm fell apart. It was reunited by Otto I of Germany who had followed Charlemagne's example of the path to power through crusades against non-Christians (in this case, the Magyars). Continuing to associate himself with Charlemagne, Otto I had himself proclaimed emperor of The Holy Roman Empire of Germany in 962 CE.

Otto I then continued the policies of maintaining a Christian nation following Charlemagne's example throughout his reign and set the standard for those who would follow him. The Holy Roman Empire continued to see itself in this role as an entity championing Christian truth through warfare until, in a steady decline involving political intrigue, corruption, almost incessant war, and constant internal strife, it was dissolved in 1806 CE.

The famous French writer, Voltaire, in Chapter 70 of his 1756 CE work Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations, notes, “This agglomeration which was called and which still calls itself the Holy Roman Empire was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire” and historians since Voltaire have agreed. The Holy Roman Empire was so in name only and after the last emperor, Francis II, abdicated the throne, Napoleon disassembled the existing political structure which supported it and the territory came under French control through the Confederation of the Rhine.

Conclusion

The fall of Rome and its various causes has been the subject of debate for centuries. Even though there is presently a general consensus on the causes, no two lists emphasize the same point or even include the same reasons. Halsall offers an interesting insight into Western Rome's fall in addressing the decline of the 5th century CE:

The most ironic thing of all is that during the preceding century it is almost impossible to identify a single figure who had actually tried to cause [Rome's] demise. All the decisive acts in bringing down the Empire were carried out by people attempting to create a better position for themselves within the sorts of imperial structures that had existed in the fourth century. In a famous dictum, Andre Piganiol wrote that 'Roman civilisation did not die a natural death; it was assassinated.' Neither alternative seems correct. The Roman Empire was not murdered and nor did it die a natural death; it accidentally committed suicide. (283)

Halstall's point is that, in trying to maintain a system of government and social structure which could no longer work, Rome doomed itself to fall. Rome “accidentally committed suicide” by holding onto a model of its past which could not work anymore. The mistreatment of the Goths by Roman provincial governors, which resulted in the Goth rebellion, wars, and the Battle of Adrianople, is just one example of this. The so-called “barbarians” would no longer tolerate poor treatment at the hands of the Romans as they had in the past and as the Romans thought they should continue to do.

The attempts to revive, preserve, and force the model of the Roman Empire on an era which could no longer support it should be considered as a significant underlying cause for the fall of Rome in the west. This same passion for reviving the “glory days” of the empire also contributed to the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. The times had changed, the people had changed with it, and an outmoded form of government simply had no hope of surviving in the new political and social climate.

Forms of government, like people, do not survive by clinging to the past but by adapting to the challenges of the present and moving on toward the future. Rome was incapable of that kind of vision and so, like any entity which holds tightly to the past, it could not survive the kinds of challenges which present opportunities for change and growth.