Totila (birth name, Baduila-Badua r. 541-552 CE) was the last great king of the Ostrogoths in Italy. He was the nephew of the Gothic king Ildibad who was succeeded by Eraric the Rugian (d. 541 CE). The Goths of Italy felt that Eraric was a poor king who pursued his own interests at their expense, and this is the accepted view of history as exemplified by the historian Thomas Hodgkin's observation that "Eraric reigned only five months, during which time he performed not a single noteworthy action" (4). He was deposed and assassinated by conspirators who wished to see Totila take the throne.

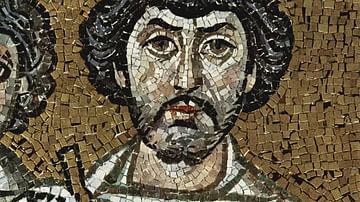

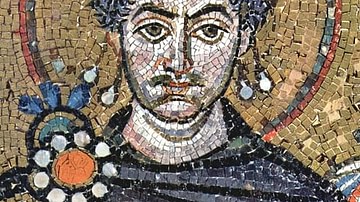

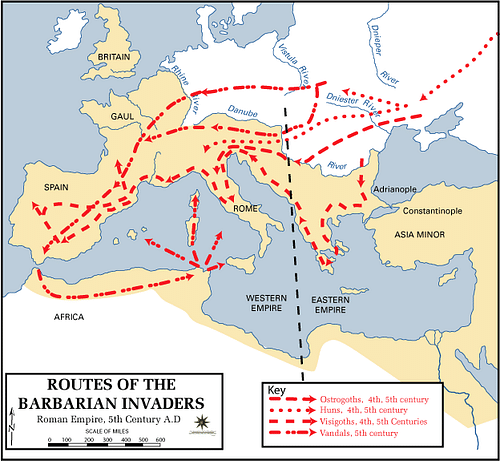

Once in power, Totila proved himself an able statesman and brilliant military commander. He led the Goths against the forces of the Eastern Roman Empire in a number of successful engagements before his defeat and death at the Battle of Taginae in 552 CE. He is often referred to as the last of the great Gothic kings and is frequently compared to Theodoric the Great (r. 493-526 CE). After Totila's defeat at Taginae, the Goths continued their resistance to Roman rule but were eventually crushed and Rome reasserted control of Italy until the 568 CE invasion of the Lombards.

Rise to Power

After the death of Theodoric in 526 CE, the land was ruled by a succession of incompetent kings, from the usurper Theodahad to the ineffective Witigis (r. 536-540 CE) and on to the self-centered Eraric. The Eastern Roman Empire, which had supported Theodoric's reign, also profited by it through taxes. These taxes increased after Theodoric's death and were overseen and managed by a special class of officials known as Logothetes. Hodgkin writes, "Both justice and expediency were disregarded by the freshly appointed Logothetes, and especially by the chief of the new department" (2). This chief was known as "Alexander the scissors" because he was so greedy that it was thought he could skillfully clip a gold coin for his own profit and return it to the treasury "still in perfect roundness" without being detected.

Alexander was chiefly responsible for enforcing the tax laws and overseeing veteran's pensions. In his capacity as comptroller of the military, he was well known for keeping veterans on the pension payroll, even after they had died; he was thus able to take their pensions for himself. His abuses were far from secret, but nothing was done to address them, since the other Logothetes prospered from them as well.

Along with the oppressive tax burden, the people felt they were being persecuted by their own government through low pay for service in the military, lack of promotion unless by special favor or nepotism, and the withholding of due pensions.

Alexander further alienated the Romans of Italy by forcing anyone who had once dealt with Theodoric in any financial capacity whatsoever to produce receipts and account for all monetary transactions they had engaged in during Theodoric's reign. Everything Alexander did seemed to enrich only Alexander and those around him at the expense of the people, while the king did nothing to stop him. Hodgkin writes, "By all these causes the smoldering embers of the Gothic resistance were soon fanned into a flame" (3-4).

The Goths had no leader, however, until election lighted upon Totila. Historian Herwig Wolfram comments on Totila's name citing "evidence from coin inscriptions and some literary sources" and observes that "we do not know what 'Totila' signifies [but] his original name [Baduila-Badua] means 'the fighter' or 'the warrior'" (353). Why he changed his name (or why it was changed) is unknown. Hodgkin comments on this writing:

The unanimous testimony of the coins of the new King proves that Baduila was that form of his name by which he himself chose to be known. From some cause, however, which has not been explained, he was also known even to the Goths as Totila, and this name is the only one which seems to have reached the ears of the Greek historians. (5)

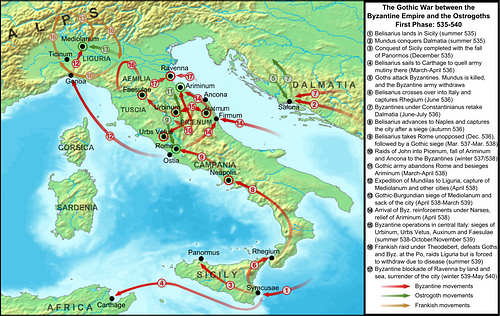

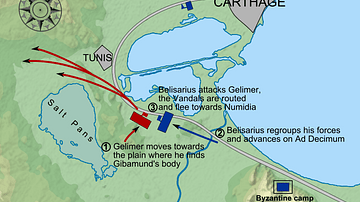

After Eraric was assassinated, Totila was "raised on the shield as King" and ruled for the next eleven years. By all accounts, even those of his enemies, he was "a valiant soldier and an able statesman" who redressed the wrongs of his people and defended Italy against the incursions of the Eastern Roman Empire. After Theodoric's death and the mess his successors made of rule in Italy, the Emperor Justinian wanted the region back directly under his control. His general Belisarius (l. 505-565 CE) had accomplished this for him, but Justinian was jealous of Belisarius' popularity and recalled him to Constantinople. This decision gave the region back to the Goths who, under Totila now, fought for their independence from the empire.

Totila's Reign and Military Engagements

News of the young king's rise to power reached Constantinople, and Emperor Justinian ordered his generals in Ravenna to march against Totila. Wolfram describes the beginning of the war:

Twelve thousand soldiers, the entire field army in Italy, left the area around Ravenna and marched north against Verona...While the generals were already dividing the spoils before they had won them, the campaign ground to a halt in a manner fit for a comedy show. The imperial army withdrew to the region between the river Reno and Faventia-Faenza, southwest of Ravenna. Totila called up his entire army of five thousand men and went in pursuit. (354)

The "comedy show" aspect of the campaign Wolfram refers to was due to the eleven generals who led the army and their insatiable greed. Hodgkin writes:

With the smallest fraction of military capacity the important city of Verona would now have been recovered for the Emperor. But the eleven generals, having started with the bulk of the army at the appointed time, began, when they were still five miles distant, to dispute as to the division of the spoil. (6)

This gave Totila, with his much smaller force, time to arrange his army skillfully for a pincer movement, which would surround the imperial forces and then close on them. He sent 300 men in a wide arc around the imperials to fall upon their rear and then launched a frontal assault. The imperial army was already suffering tremendous losses when the 300 Goths attacked from the rear. The imperials, thinking these men were the vanguard of another, larger, army, broke ranks and began to run from the field in a full-scale rout. Those imperials who were not killed were captured along with all the standards of the army.

This great victory in 542 CE brought scores of recruits to Totila's banner, swelling his ranks to over 20,000 men, many of whom had formerly fought for the empire. With this force he marched across the Apennines and lay siege to Florence. An imperial force was sent to relieve the city and drove the Goths into the nearby valley of Mugello. Totila, however, knew the region well and positioned his army at a high point in the valley from which, once the imperial army was arrayed below, he fell upon them with such force that their lines were broken almost immediately and the battle became another rout.

Those who were taken prisoner were treated well and invited to join Totila's army. Those who escaped, according to Hodgkin, went "galloping on for days through Italy, pursued by no man, but bearing everywhere the same demoralizing tidings of rout and ruin, and rested not till they found themselves behind the walls of some distant fortress, where they might at least for a time breathe in safety from the fear of Totila" (7-8). The imperial generals expected Totila to now return to his siege of Florence but, instead, he marched from Mugello into southern Italy and took the city of Beneventum, then the city of Cumae, and so on until the south of Italy was completely under his control.

The Siege of Naples and Rome

Totila then lay siege to Naples which eventually fell in 543 CE. His treatment of the garrison and the civilian population was so chivalrous and kind that even more soldiers flocked to his cause. The Roman imperial army was disintegrating in Italy, as more and more deserted the imperial standard for Totila's. Hodgkin writes, "The oppressions of the Logothetes had revealed to all men that one great motive for the Imperial reconquest of Italy was revenue; and Totila, by anticipating the visit of the tax-gatherer, stabbed Justinian's administration in a vital part" (8). The cities he had conquered were no longer, of course, paying their taxes to the emperor but to Totila.

The so-called "barbarian auxiliaries" of the imperial army could not be paid and so deserted en masse to Totila along with many regular soldiers of the imperial forces. Totila's string of military victories continued until, by December of 545 CE, he stood before the walls of Rome itself and lay siege to the city. Part of his success was due to his military skill, part to the incompetent generals of the imperial army, and a large part to Totila's impressive diplomatic abilities. Wolfram writes:

The Gothic successes of 545, which were even surpassed by those in 546, were possible in large measure because Totila's diplomacy had eliminated the Frankish threat...The friendly neutrality of the most important Frankish king meant that the Gothic rear was secure. (355-356)

King Theudebert of the Franks was handsomely rewarded by Totila for his neutrality in the conflict and refused the imperial request that he allow forces to make use of his land routes to attack Totila.

Rome fell when the Isaurian soldiers guarding the gates secretly invited Totila to take the city. Like many in the imperial army, they had not been paid in months and did not think it wise to risk their lives against a general who had thus far won every battle he engaged in. As with the other conquered cities, Totila treated the Romans with the utmost kindness and respect and, having now conquered the symbolic seat of Roman power in Italy, he opened communications with Constantinople to offer peace.

The emperor was not interested in speaking with him, however, and word came back that he should deal with General Belisarius who had recently arrived in the country to command the imperial forces. Totila then sent his emissaries to Belisarius with the message that, if the imperial forces were not withdrawn from Italy and if he were not recognized as the legitimate king by the empire, he would destroy Rome and execute the senators before marching on to raze other cities still loyal to the empire.

At this point, Belisarius' skill in diplomacy inflicted a serious defeat on Totila - the first the Gothic king had experienced - simply by writing him a letter. Belisarius made it clear that the empire could not possibly recognize Totila as the legitimate ruler of Italy because Italy rightfully belonged to the empire and Justinian was not interested in giving it up. Regarding Totila's threat to destroy Rome and murder the senators, Belisarius appealed to Totila's chivalry and honor. He noted the kindness Totila regularly showed to prisoners and emphasized the long history of the city of Rome and what a tragic mistake it would be on Totila's part to destroy it.

Belisarius wrote that, if Totila destroyed Rome, no good could come of it; if Totila won this war, he would have to rebuild the city he had destroyed at great expense, while if he lost, the empire would show no mercy to someone who razed Rome. Further, the great fame of the city would attach itself forever to Totila's name; if he showed mercy and left it intact, he would be remembered well by history, and if he did not, his name would be held in dishonor by future generations.

Wolfram comments on what happened next, writing, "And now Totila committed - or was he compelled to commit? - the momentous mistake of giving up Rome" (356). He could not simply keep his forces in Rome while there was still a war to be fought, nor could he leave a garrison of his soldiers behind because he felt he would need every man in the coming months to defeat the empire. Some historians have claimed that Totila simply marched out of Rome, while others, citing the same sources, argue that he tried to secure the city and, when that failed, he left it to the Romans. Wolfram, for example, writes:

It is not true that Totila abandoned the city carelessly; all attempts to secure and hold it must have failed because of the sheer size of Rome...Thus Totila lost his first 'battle for Rome' and with it much of his prestige. As late as 549/550, just before his second capture of the city, his suit for the hand of one of the daughters of a Frankish king was rejected with reference to this debacle. (356)

Belisarius marched his troops into Rome, repaired the walls, and fortified the city against future attacks. Totila, meanwhile, continued the war against the empire throughout Italy. He liberated the slaves of the Roman elite in the country and took special pains to ensure the safety of the common people and their lands. Wolfram notes that this tactic has been called "revolutionary" but argues that "what Totila did was not revolutionary; rather it was a shrewdly calculated, effective means of waging war" (356-357). The empire had inexhaustible resources, while Totila's were limited to the country of Italy. It therefore made sense to protect the land and its people as much as he possibly could. Unlike the imperial forces, Totila could not expect supplies from other lands; he had to make sure he could feed his troops from the produce of Italy.

Totila's Success and the Coming of Narses

Not only were his troops fed gladly by the peasant farmers but many joined his army. Between 547-548 CE, he experienced a number of victories but also a series of defeats and yet, even so, deserters from the imperial army continued to swell his ranks, along with farmers and other civilians who hoped for a free Gothic nation under Totila's rule. In the summer of 549 CE, he returned to besiege Rome.

The siege lasted until 16 January 550 CE when, as before, Isaurian soldiers guarding the gates, who again had not been paid in months, opened the way for Totila's forces. This time, however, the Roman garrison was not going to give up so easily and fought for their city with great loss of life. Those who survived the battle in the streets were allowed to leave the city in peace if they chose; many, instead, joined Totila's army.

With Rome again under his control and even more of the country conquered, Totila again sent emissaries to Constantinople requesting peace with the empire. In case his offers should be refused, he led part of his army to Sicily and conquered it in 550 CE, thus cutting off an important source of supply and trade to the empire. It is thought that perhaps Totila felt this victory would improve his bargaining power with the emperor. Before Justinian even heard of the Sicily campaign, however, he gave his answer: Totila's emissaries were denied admittance to his presence and then arrested.

Justinian called Belisarius back from Italy and appointed his cousin Germanus as high commander. Germanus was the husband of Theodoric the Great's granddaughter and was highly regarded by the Goths. Justinian's strategy was to win back those troops who had deserted to Totila by sending a member of Theodoric's family as head of imperial forces. Germanus, however, died of disease in the summer of 550 CE before reaching Italy and was replaced by another general named Narses (l. c. 480-573 CE).

Narses was a eunuch at the court who was in charge of the treasury but, prior to this, had commanded troops under Belisarius. He was a very religious man and highly respected by his troops. He landed in Salona in the summer of 551 CE and, almost immediately, turned the tide of the war in favor of the empire. Gothic morale was low. The emissaries who had been sent to Constantinople were finally released and returned with the message from Justinian that there would be no peace and the war would continue.

The Gothic army had recently suffered another defeat, and their newly built fleet had been badly beaten by the imperial navy in a raid on the Greek mainland. Totila took Sardinia and Corsica in 551 CE and, with the interior of Italy securely under his control, felt he would still win the war no matter what forces Justinian sent against him. The interior of Italy was completely his, his alliance with the Franks still held, and he now had Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica as important sources for supplies; he would soon have all of Italy under his control, and Justinian would have no choice but to sue for peace.

He would probably have been correct in this if he had not been facing a general like Narses. Narses quickly evaluated the situation in Italy, recognized that it was pointless to engage in city-to-city battles across hostile terrain to reach the remaining imperial army in Ravenna, and so devised a plan no one could have foreseen. Wolfram describes the situation:

Neither the Franks nor the Goths paid any attention to the coastline, since they both considered it trackless because of its many estuaries and marshes. Yet the unimaginable happened: led by superb guides, Narses moved with a gigantic army of close to thirty thousand men along the coast toward Ravenna. The water courses were crossed on portable pontoon bridges; in this way all Gothic defenses in the interior were circumvented. (359)

Historian J.F.C. Fuller adds that the imperial fleet followed the troops on land and "ferried them across the estuaries of the numerous Venetian rivers and lagoons" (323). All this was accomplished without alerting the Goths. Narses entered Ravenna in June 552 CE, resupplied his troops, and then marched toward Rome. He took Rimini easily and continued on toward Fano, routing whatever Gothic resistance he met.

The Battle of Taginae

In late June or early July, Narses found himself in proximity to Totila's army which was marching from Rome to meet him. He pitched camp somewhere between Scheggia and Tadino in the Apennine ridge, choosing the high ground carefully so that he could arrange his army above a narrow plain through which Totila's forces would have to pass to meet him. Totila, meanwhile, had encamped 13 miles away at the village of Taginae. Narses sent messengers to ask the Gothic king when he would be ready to join in battle. Totila responded that he would be ready in eight day's time, but actually planned to attack the imperials the next day.

Narses received the reply but dismissed it as a ploy and rightly guessed at Totila's actual intentions. He therefore moved his army into position on the high ground of the plateau of Busta Gallorum and waited for his opponent's advance. Narses "arranged no less than eight thousand archers in a crescent-shaped formation well adapted to the broken ground" (Wolfram, 360). Behind the archers he placed his foot soldiers in phalanx formation and set his cavalry on the wings.

Fuller, citing the scholar Sir Charles Oman, notes that this particular formation "seems to have been his own invention", and that Narses took care to place the center of his line far back from the flanking archers "so that an enemy advancing against the centre would find himself in an empty space, half encircled by bowmen and exposed to a rain of arrows from both sides" (325-326). Narses gave orders that no one was to break ranks and meals would be taken in position, in full gear, until the battle was won.

Totila moved his army forward from Taginae and arranged them on the other side of the plain. He placed his cavalry in front, as was customary, and his infantry in the rear. Fuller notes that "his idea was to win the battle by a single charge which would break his enemy's centre. According to Procopius, he ordered his entire army 'to use neither bow nor any other weapon...except the spear'. Should this be true, it may well be asked what purpose he hoped to achieve with his infantry?" (324-325). Totila's son, Teias, was commanding 2,000 cavalry, which were separated from the main army, and Totila needed to stall for time.

He put on his most splendid armor and rode to the area between the two armies, where he performed the "djerid", a mounted lance-ride demonstration/dance, which Procopius describes as being admired by friend and foe alike. When he was done, he rode back to his lines where he found Teias had arrived with the cavalry. He took off his parade armor and changed into his battle armor so as to appear as just another member of the cavalry and not draw attention to himself as the king of the Goths.

Shortly after mid-day the battle began with a skirmish in which 50 imperial soldiers took and held a nearby hill and drove the Goth forces back to their lines. Totila hoped he would be able to charge unexpectedly across the plain and catch Narses' men at lunch, but he would have no such luck. Fuller gives an account of the battle based on Procopius' description:

The Goths took no notice of the bow-wings of their enemy's line and charged straight forward against the phalanx of the dismounted barbarians [at the centre] with the inevitable result that, while their central squadrons failed to break through its bristling hedge of spears, those on the flanks were raked by the Roman archers. Hundreds of Goths must have fallen immediately and scores of riderless horses have galloped away, plunging and careering over the battlefield to add confusion to the central squadrons which, presumably, were out of bow-shot. It would appear that the initial charge was the only organized one, and that those which followed were improvised by individual leaders, for no mention is made of the Gothic horse retiring behind their infantry to reorganize. Toward evening the Romans began to advance, and the Gothic cavalry, no longer able to offer resistance, gave ground and finally broke back on their infantry, not, as Procopius writes, `with the purpose of recovering their breath and renewing the fight with their assistance, as is customary but to escape. Consequently the infantry did not open intervals to receive them nor stand fast to rescue them but they all began to flee precipitately with the cavalry, and in the rout they kept killing each other just as in a battle at night'. (326-327)

Totila was mortally wounded in the battle, either early on or later (there are two different accounts) and was carried by his men to Caprae-Caprara, where he died and was quickly buried. According to Procopius, he was either killed early in the battle in the hail of arrows or was struck by a spear while fleeing the field after the failure of the first charge. Either way, Procopius notes, "his death was not worthy of his past deeds" (7.40.9).

Procopius, who presents Totila as an admirable man, general, and king throughout his work, seems disappointed with his conduct at Taginae and notes that there was no good reason to lead his army against an enemy who was so well fortified and positioned, nor did it make any sense to restrict them to only the use of the spear in battle when they had able archers in their ranks. Six thousand Goths died in the battle, and more later from their wounds. The losses to the imperial army were so slight they were not recorded. The Battle of Taginae, and the death of Totila, ended any hope of Gothic supremacy over the imperial forces of the emperor Justinian.

Aftermath and Legacy

The Goths immediately crowned Teias as their king and fled to Sarno while Narses, after paying off his mercenaries and sending them home, occupied Rome. Once he had re-supplied his troops, he pursued Teias at Sarno, who retreated to a position at Mons Lactarius where the final full-scale battle of the Gothic war was fought in October of 552 CE. Teias was killed, and the remainder of the Gothic army surrendered. They were allowed to gather what wealth and possessions they claimed and leave the country.

Some Gothic commanders continued the resistance and fought on until 555 CE with the assistance of the Franks. Narses, however, would not tolerate such a situation and destroyed the Frankish army at Capua in 554 CE using the same tactics he had employed at Taginae. He then hunted down the remaining Gothic leaders in the resistance and executed them. Italy was again under the rule of the Eastern Roman Empire, and the Logothetes returned to prey on the people until the Lombard invasion in 568 CE.

Although Totila lost the Battle of Taginae, the war, and his life, he is remembered as the last great king of the Ostrogoths, who tried to free the land of the Goths from the grip of Rome. Procopius refers to him constantly as "honorable", "just", "compassionate", and "courageous", even though Procopius was writing from a Roman point of view and, typically, Roman writers did not elevate the characters of enemies of the state. Historians speculate that, had Totila lived, he would probably have been an even greater ruler than Theodoric; as it was, however, he is remembered as a noble champion of his people who fought, and died, for his people.