In many societies, ancient and modern, religion has performed a major role in their development, and the Roman Empire was no different. From the beginning Roman Religion was polytheistic. From an initial array of gods and spirits, Rome added to this collection to include both Greek gods as well as a number of foreign cults. As the empire expanded, the Romans refrained from imposing their own religious beliefs upon those they conquered; however, this inclusion must not be misinterpreted as tolerance - this can be seen with their early reaction to the Jewish and Christian population. Eventually, all of their gods would be washed away, gradually replaced by Christianity, and in the eyes of some, this change brought about the decline of the western empire.

Early Beliefs & Influences

Early forms of the Roman religion were animistic in nature, believing that spirits inhabited everything around them, people included. The first citizens of Rome also believed they were watched over by the spirits of their ancestors. Initially, a Capitoline Triad (possibly derived from a Sabine influence) were added to these “spirits" - the new gods included Mars, the god of war and supposed father of Romulus and Remus (founders of Rome); Quirinus, the deified Romulus who watched over the people of Rome; and lastly, Jupiter, the supreme god. They, along with the spirits, were worshipped at a temple on Capitoline Hill. Later, due to the Etruscans, the triad would change to include Jupiter who remained the supreme god; Juno, his wife and sister; and Minerva, Jupiter's daughter.

Due to the presence of Greek colonies on the Lower Peninsula, the Romans adopted many of the Greek gods as their own. Religion and myth became one. Under this Greek influence, the Roman gods became more anthropomorphic – with the human characteristics of jealousy, love, hate, etc. However, this transformation was not to the degree that existed in Greek mythology. In Rome individual expression of belief was unimportant, strict adherence to a rigid set of rituals was far more significant, thereby avoiding the hazards of religious zeal. Cities adopted their own patron deities and performed their own rituals. Temples honoring the gods would be built throughout the empire; however, these temples were considered the “home” of the god; worship occurred outside the temple. While this fusion of Roman and Greek deities influenced Rome in many ways, their religion remained practical.

Even though there were four colleges for priests, there was no priestly class; it would always remain a public office. This practice would even extend to the imperial palace. From the time of Emperor Augustus the emperor would assume the title of pontifex maximus or chief priest. Other than the pontifexes there were augures, individuals who read the entrails of animals and the flight of birds to interpret omens, or in other words, the will of the gods. Elaborate rituals were performed to bring Roman victory in battle, and no declaration of war or major event was undertaken without the clear approval of the gods. Dating from the time of the Etruscans, a diviner or haruspices, was always consulted, and it was considered dangerous to ignore the omens. Spurinna, a Roman soothsayer, read animal entrails and foresaw Julius Caesar's death on the Ides of March. When Roman Commander Publius Claudius Pulcher ignored the omens - refusal of the sacred chickens to eat - before a battle during the First Punic War, he was defeated, as was his military career.

As the empire expanded across the Balkans, Asia Minor and into Egypt, Roman religion absorbed many of the gods and cults of conquered nations, but the primary influence would always remain Greece. With only a few exceptions, most of the Roman gods had their Greek counterparts. This Roman mythology would have a significant influence on the empire - politically and socially - as well as on the future of western civilization. One needs only to look at the names of the days and months (Tuesday, Saturday, January and June), the languages of European nations, and the names of the planets (Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Pluto) to realize this influence.

The Roman Pantheon

While the study of Roman mythology tends to emphasize the major gods - Jupiter, Neptune (god of the sea), Pluto (god of the underworld) and Juno - there existed, of course, a number of “minor” gods and goddesses such as Nemesis, the god of revenge; Cupid, the god of love; Pax, the god of peace; and the Furies, goddesses of vengeance.

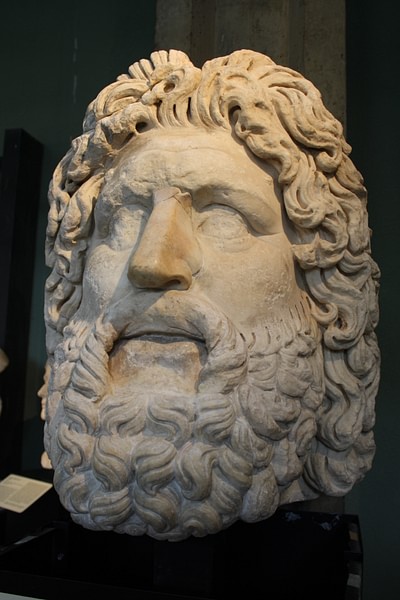

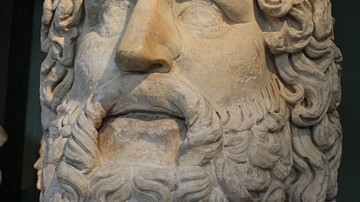

However, when looking at the religion of Rome, one must examine the impact of the most important gods. Foremost among the gods were, of course, Jupiter, the Roman equivalent of Zeus (although not as playful), and his wife/sister Juno. He was the king of the gods; the sky god (the great protector) - controlling the weather and forces of nature, using thunderbolts to give warning to the people of Rome. Originally linked with farming as Jupiter Elicius, his role changed as the city grew, eventually obtaining his own temple on Capitoline Hill. Later, he became Jupiter Imperator Invictus Triumphator - Supreme General, Unconquered, and ultimately, Jupiter Optimus Maximus - Best and Greatest. His supremacy would be temporarily set aside during the reign of Emperor Elagabalus who attempted to replace the religion of Rome with that of the Syrian god Elagabal. After the emperor's assassination, his successor, Alexander Severus, returned Jupiter to his former glory. Next, Jupiter's wife/sister was Juno, for whom the month of June is named - she was the equivalent of the Greek Hera. Besides being the supreme goddess with a temple on Esquiline Hill, she was the goddess of light and moon, embodying all of the virtues of Roman matron hood - as Juno Lucina she became the goddess of childbirth and fertility.

After Juno comes Minerva, the Roman name for Athena (the patron goddess of Athens), and Mars, the god of war. According to legend, Minerva sprang from Jupiter's head fully formed. She was the goddess of commerce, industry, and education. Later, she would be identified as a war goddess as well as the goddess of doctors, musicians and craftsmen. Although no longer one of the Capitoline triad, Mars remained an important god to Rome - similar to Ares, the Greek god of war. As Mars the Avenger, this son of Juno and her relationship with a flower, had a temple dedicated to him by Emperor Augustus, honoring the death of Julius Caesar's assassins. Roman commanders would make sacrifices to him before and after battles and Tuesday (Martes) is named for him.

There are a number of lesser gods (all with temples built to them) - Apollo, Diana, Saturn, Venus, Vulcan, and Janus. Apollo had no Roman equal and he was simply the Greek god of poetry, medicine, music, and science. He was originally brought to the city by the Etruscans to ward off the plague and was rewarded with a temple on Palatine Hill. Diana, Apollo's Roman sister equivalent to the Greek Artemis, was not only the goddess of wild beasts and the harvest moon but also the goddess of the hunt. She was seen as a protector of women in childbirth with a temple at Ephesus in Asia Minor. Another god brought to the Rome by the Etruscans was Saturn, an agricultural god equal to the Greek Cronus and who had been expelled from heaven by Jupiter. A festival in his honor, the Saturnalia, was held yearly between the 17th and 23rd of December. His temple, at the foot of Capitoline Hill, housed the public treasury and decrees of the Senate. Another Roman goddess was Venus, who was born, according to myth, from the foam of the sea, equal to the Greek Aphrodite. According to Homer, she was the mother of Aenaes the hero of the Trojan War. Of course, the planet Venus is named for her. Next was Vulcan, also expelled from heaven by Jupiter, who was a lame (caused by his expulsion), ugly blacksmith and the god of fire. Lastly, there was Janus who had no Greek equal. He was the two-faced guardian of doorways and public gates. Janus was valued for his wisdom and was the first god mentioned in a person's prayer; because of his two faces he could see both the past and the future.

One cannot forget the Vestal Virgins who had no Greek counterpart. They were the guardians of the public hearth at the Atrium Vesta. They were girls chosen only from the patrician class at the tender age of six, beginning their service to the goddess Vesta at the age of ten and for the next thirty years they would serve her. While serving as a Vestal Virgin, a girl/woman was forbidden to marry and had to remain chaste. Some chose to remain in service to Vesta after serving their thirty years since, at the age of forty, they were considered too old to marry. Breaking the vow of chastity would result in death - only twenty would break the vow in over one thousand years. Emperor Elagabalus attempted to marry a vestal virgin but was convinced otherwise.

Cult Worship

Besides the worship of these gods there were several cults - Bacchus, Cybele, Isis, Sarapis, Sibyl, and most of all the Imperial Cult. Some were readily accepted by Roman society while others were feared by those in power. Bacchus was a Roman deity associated with both the Greek god Dionysus and the early Roman god Liber Patri, also a wine god. Bacchus is best remembered for his intoxicating festivals held on March 17, a day when a Roman male youth would supposedly become a man. As his cult spread, the Roman Senate realized its dangerous potential and ordered its suppression in 186 BCE and afterwards, the cult went underground.

Another cult centered on Cybele, the “great mother” - a fertility goddess with a temple on Palatine Hill who was responsible for every aspect of a person's well-being. The goddess arrived in Athens in the fifth century BCE and first appeared in Rome during the Punic Wars. All of her priests were eunuchs, and many of her male followers would have themselves castrated. Next is Isis, the ancient goddess of Egypt who is best remembered in Egyptian mythology as the wife of Osiris and the mother of Horus. After becoming Hellenized, she became the protector of sailors and fishermen. Arriving in Rome from Alexandria, Sarpis was a healing god and the sick would travel to her temple to be cured. Sibyl was a priestess of the Greek and Roman god Apollo who came to Rome from the Greek colony of Cumae. She offered the Etruscan King Tarquin the nine Sibylline Books which were books of prophecy, but the price was considered too high, so he refused. After she had burned six of the books, he reconsidered and bought the remaining three; these three books were consulted by the Roman Senate in times of emergencies but they were lost during the barbarian invasions of the fifth century CE.

Lastly, there was the Imperial Cult. The idea of deification of the emperor came during the time of Emperor Augustus. He resisted the Senate's attempts to name him a god during his reign as he thought himself the son of a god, not a god. Upon his death, the Roman Senate rewarded him with deification which was an honor that would be bestowed upon many of his successors. Often, an emperor would request his predecessor to be deified. Of course there were a few exceptions, notably, Tiberius, Caligula, Nero and Domitian, who were considered too abhorrent to receive the honor. Caligula and Nero believed themselves living gods while Domitian thought himself the reincarnation of Hercules.

Roman Religion Challenged

Judaism and Christianity, while posing separate threats to the empire, had one thing in common - they both refused to participate in the worship of the Roman gods and make sacrifices at their temples. Although the Jews had firmly established themselves in the empire, they were often the target of the emperors, often blamed for any ills that befell the empire. Nero had them expelled from Rome, and Titus, the son of Emperor Vespasian, would continue his father's war against the Jews in the Jewish Wars, eventually destroying the city of Jerusalem and killing thousands of its citizens.

Although Christianity was initially seen as a sect of Judaism, Emperor Nero grew more suspicious as this small sect began to grow, especially after the Great Fire of Rome; he even blamed them for the fire. They returned the favor, calling him the anti-Christ. As time passed, Christianity continued to spread across the empire, appealing to women and slaves as well as intellectuals and the illiterate. Persecutions increased where Christian churches were burned and all of this continued under the reign of Diocletian (emperor in the east), ending in the Great Persecution. To many, Christians offended the pax deorum or “peace of the gods".

Finally, under Diocletian's successor Emperor Constantine, Christianity would finally receive recognition in the Edict of Milan in 313 CE. Constantine's benevolence towards Christianity can be traced to the Battle of Milvan Bridge in 312 CE where he beheld a vision (a cross in the sky), enabling him to be victorious and become the emperor of a united Roman Empire. Later, in 325 CE he held the Council of Nicaea, reconciling the differences between the various Christian sects. He rebuilt the churches destroyed by Diocletian, and according to some sources, converted to Christianity on his deathbed (his mother was a Christian). After his death Christianity would continue to grow and eventually overshadow and replace the traditional Roman religion and Rome would even become the new center of Christianity. However, in the end, Christianity would still receive blame for the ills of the empire. In his book The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire Edward Gibbon blamed, in part, the fall of the empire on Christianity. In his eyes it absorbed the energy of the people making them unable to suffer through the adversities that plagued the empire. Yet, despite its highs and lows, from the days of the spirits inhabiting all things through the Roman/Greek gods and emperor deification to Christianity, religion always remained an important part of Roman society.