The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (French: Declaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen) is a human rights document adopted in the early stages of the French Revolution (1789-1799). Inspired by Enlightenment Age principles, the Declaration consisted of 17 articles and served as the preamble to the French Constitution of 1791.

Originally drafted by Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), the document was based on concepts such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau's (1712-1778) general will theory, the separation of powers, and the idea that all men were subject to universal and natural human rights. The Declaration, first adopted in August 1789, served as an affirmation of the core values of the French Revolution and had a major impact on the development of liberty and democracy in Europe and across the world.

Although initially seen as an almost sacred document, the Declaration would be amended several times during the Revolution, first to fit the Constitution of 1793, and again for the Constitution of 1795 (Year III in the French Republican Calendar). However, the original 1789 version remains the most historically significant and has been included in preambles to the constitutions of both the Fourth French Republic (1946-1958) and the current Fifth French Republic (1958-present).

Origins

The summer of 1789 was a hopeful time for France. The three estates of pre-revolutionary France had reconciled into a single National Constituent Assembly, which had dismantled the shackles of feudalism and deprived the nobility and clergy of their privileges with the August Decrees. The common people had made their own voices heard with the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July, forcing stubborn King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) to reluctantly, and temporarily, comply with the Revolution. With the blood-soaked months of the Reign of Terror (1793-94) still years in the future, the summer of 1789 witnessed a peaceful and orderly Revolution, in which reconciliation with the king still seemed possible, and the French Revolutionary Wars were not yet a foregone conclusion. For many Frenchmen, this summer held a promise that a better life was just around the corner.

It was amidst this optimistic atmosphere that the Assembly approved the Declaration of the Rights of Man on 26 August 1789. The document, including a preamble text and seventeen articles, was meant to be merely provisional, to be amended as needed as the Assembly embarked on the laborious task of negotiating a new constitution. However, when the constitution was finalized two years later, no one dared offer revisions to the Declaration. By then, it had become practically sacred.

The French Declaration, birthed from Enlightenment ideals, took inspiration from the recent American Revolution, which many starry-eyed Assembly deputies saw as the premier success story of freedom triumphing over tyranny. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the Declaration's original author was Lafayette, a champion of American liberties who now sought to deliver those freedoms to his own countrymen. Vocally supported by other French veterans of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), Lafayette first proposed the need for an affirmation of citizens' natural rights to the Assembly on 11 July, a mere three days before the Bastille fell. The Storming of the Bastille, which strengthened the Revolution and gave Lafayette himself a position of authority as commander of the National Guard, could hardly have seemed like a better mandate for him to continue his work.

Lafayette worked closely under the guidance of his personal friend Thomas Jefferson (1743-1824), then serving as the United States ambassador to France. Although Jefferson declined the Assembly's offer to advise them in a formal capacity, citing duties to his own country, he made sure to read every draft Lafayette sent him, offering edits and considerations where he saw fit. Naturally, the resulting French Declaration closely mirrored American examples, specifically the Virginia Declaration of Rights and the American Declaration of Independence, both authored by Jefferson. As historian Ian Davidson notes, the French and American declarations are similar not only in their espousals of the natural rights of men but also as declarations of war and manifestos against tyranny: the Declaration of Independence was a declaration of war against King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820), while the French Rights of Man was a declaration of war against the Ancien Régime.

Yet, the French Declaration of Rights was not without its critics. Some within the Assembly disliked Lafayette's emulation of the American experience, pointing out that the two situations were completely different; the United States was a new nation, which was creating a separate identity for itself from scratch after casting off the yoke of its colonial rulers. By contrast, France was an ancient nation, which had known the rule of kings for over a millennium. Rather than crafting a completely new government, France was faced with the difficulty of establishing a new body politic within the confines of an existing government and of factoring the king's presence into any Declaration of Rights it approved. As the Comte de La Blanche crudely described the comparison, "We should not forget that the French are not a people who have just emerged from the depths of the woods to form an original association" (Schama, 443).

This led to debate within the Assembly on what exactly a finished version of the Declaration should look like. Deputies in the monarchien (monarchist) faction argued that the Assembly should focus on the rights of the king with as much vigor as it was focusing on the rights of the citizen. It was imperative to the monarchiens that the king remain France's supreme executive power with the right to an absolute veto over any decision the Assembly made.

In stark contrast stood the anti-royalist deputies, some of whom believed they had a duty to go even further than the Americans had. Chief among these was Abbé Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748-1836), whose seminal pamphlet What is the Third Estate? had contributed significantly to the creation of the Assembly. Sieyès criticized the Americans for being limited in their vision, clinging to old ideas of power and authority, and contributed to further drafts that closer conformed to his goal of a "people resuming its full sovereignty" (Furet & Ozouf, 821).

The debate over the Declaration began in the Assembly on 1 August, was interrupted on the 4th while the deputies turned their attention to dismantling feudalism, and resumed on the 12th. A committee was then formed to sift through the various proposals submitted by deputies. The proposals were whittled down into 17 articles, which were accepted by the Assembly on 26 August as a preamble that would be attached to the forthcoming constitution upon its completion.

Articles

The Declaration begins with its own preamble, describing the characteristics of man's rights to be unalienable, natural, and sacred. It echoes the Assembly's previous destruction of feudalism and noble privileges while also restricting the monarchy and emphasizing the rights of all citizens to partake in the democratic process, through methods such as freedom of speech and expression. The Declaration embraces the theory of the general will put forth by Enlightenment philosopher Rousseau, which posits that the state represents the will of the citizens and that laws cannot be rightfully enforced without the peoples' consent.

The articles also contain other Enlightenment ideas, such as the separation of powers urged by Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755) and the notion that the individual must be safeguarded against arbitrary imprisonment, an echo of Voltaire (1694-1778). The influence of the physiocrats, an economic school of thought which viewed land as the source of wealth, is also prevalent in the Declaration's emphasis on the importance of property.

Significantly, and in contrast to the American Declaration of Independence, the French articles say nothing about the offenses of King Louis XVI and, indeed, say nothing about whether there should be a king at all. The articles do, however, offer the idea of popular sovereignty as a replacement for the concept of a king’s divine right to rule.

Below are the 17 articles (translation from Yale Law School's Avalon Project):

- Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

- The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

- The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.

- Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law.

- Law can only prohibit such actions as are hurtful to society. Nothing may be prevented which is not forbidden by law, and no one may be forced to do anything not provided for by law.

- Law is the expression of the general will. Every citizen has a right to participate personally, or through his representative, in its foundation. It must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes. All citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, are equally eligible to all dignities and to all public positions and occupations, according to their abilities, and without distinction except that of their virtues and talents.

- No person shall be accused, arrested, or imprisoned except in the cases and according to the forms prescribed by law. Anyone soliciting, transmitting, executing, or causing to be executed, any arbitrary order, shall be punished. But any citizen summoned or arrested in virtue of the law shall submit without delay, as resistance constitutes an offense.

- The law shall provide for such punishments only as are strictly and obviously necessary, and no one shall suffer punishment except it be legally inflicted in virtue of a law passed and promulgated before the commission of the offense.

- As all persons are held innocent until they shall have been declared guilty, if arrest shall be deemed indispensable, all harshness not essential to the securing of the prisoner's person shall be severely repressed by law.

- No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law.

- The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write, and print with freedom, but shall be responsible for such abuses of this freedom as shall be defined by law.

- The security of the rights of man and of the citizen requires public military forces. These forces are, therefore, established for the good of all and not for the personal advantage of those to whom they shall be entrusted.

- A common contribution is essential for the maintenance of the public forces and for the cost of administration. This should be equitably distributed among all the citizens in proportion to their means.

- All the citizens have a right to decide, either personally or by their representatives, as to the necessity of the public contribution; to grant this freely; to know to what uses it is put; and to fix the proportion, the mode of assessment and of collection and the duration of the taxes.

- Society has the right to require of every public agent an account of his administration.

- A society in which the observance of the law is not assured, nor the separation of powers defined, has no constitution at all.

- Since property is an inviolable and sacred right, no one shall be deprived thereof except where public necessity, legally determined, shall clearly demand it, and then only on condition that the owner shall have been previously and equitably indemnified.

The Declaration in Relation to Women & Slavery

Certainly, the Declaration was a watershed moment in the history of human rights, going further in scope than most of the similar documents that came before. Yet, the rights it entailed were by no means extended to everyone. At the time of its framing, active citizenship was only granted to male property owners over the age of 25 who paid their taxes and could not be defined as servants. This amounted to roughly 4.3 million Frenchmen out of an approximate population of 27 million. Women, slaves, and foreigners were thereby omitted from the democratic process.

With the atmosphere of revolutionary change already hanging in the air, it did not take long for this status quo to be challenged. Shortly after the Women's March on Versailles in October, a petition was sent to the National Assembly that proposed a decree proclaiming women's equality. The writers of the petition expressed their anger at the Declaration's hypocrisy, which cast down the privileges of the upper classes even as it upheld the privileges of the male sex. The petition, which also called for the abolition of slavery, stated that while the Assembly had "divined the true equality of rights," it still "unjustly with[held] them from the sweetest and most interesting half among you!" (Women's Petition to the National Assembly).

The petition was not well received. Although some deputies were sympathetic, others claimed that these women were merely suffering from hysterics due to the stresses of a rapidly changing society. Outrage and frustration that women's rights had not been considered led the playwright Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793) to pen the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in September 1791. A direct response to the Rights of Man, de Gouges sought to expose the failure of the Revolution to live up to its promises of equality. De Gouges followed the original declaration point by point, using sarcasm to underscore the Assembly's hypocrisy in what has been described as a virtual parody of the original. Although de Gouges' work led to her execution in 1793, the Declaration of the Rights of Woman brought public attention to feminist concerns.

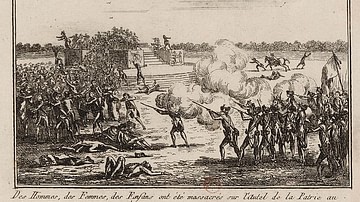

The Rights of Man also failed to end slavery, despite the efforts of Jacques-Pierre Brissot (1754-1793), who had long advocated for such with his abolitionist club Les Amis de Noirs. Although the Declaration did not mention slavery, its principles inspired many enslaved persons in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti) to revolt against their masters. These slave uprisings became the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804). The Jacobins would later abolish the practice of slavery in 1794, although it would be briefly reinstated in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) before Haiti's independence in 1804.

Conclusion

Despite its shortcomings, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was one of the most significant and enduring achievements of the French Revolution. "As far as history is concerned," writes Ian Davidson, "there is only one Declaration of Human Rights of any significance before that of the United Nations in 1948, and that is the French Declaration of 1789" (39). Although this statement is certainly arguable, the monumental impact of the Rights of Man on French and world history is not.

It did not always appear that the Declaration would endure, however. King Louis XVI refused to consent to it until the Women's March on Versailles forced him to do so in October 1789. Although the Assembly deemed it too sacred to revise for the Constitution of 1791, the shifting needs of the Revolution led to the Jacobins drafting a new version to fit their Constitution of 1793, hoping to go even further than the original in the name of democracy. This version was never implemented, however, and a third version of the Declaration was completed in 1795 as a right-wing reaction to the Reign of Terror. The Declaration in any of its forms was largely ignored by Napoleon and the restored Bourbons until the Revolution of 1830 continued to combine it with French constitutions.

Elements of the Declaration can be seen in the current constitution of 1958, established for the Fifth French Republic at the behest of General Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970). The legacy of the Declaration, originally meant as an affirmation of the core principles of the Revolution of 1789, therefore persists to this day.