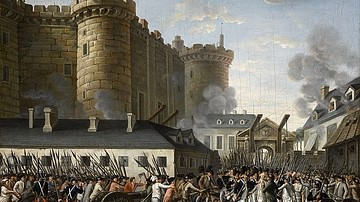

The Storming of the Bastille was a decisive moment in the early months of the French Revolution (1789-1799). On 14 July 1789, the Bastille, a fortress and political prison symbolizing the oppressiveness of France’s Ancien Régime was attacked by a crowd mainly consisting of sans-culottes, or lower classes. The anniversary is still celebrated in France as the country’s national holiday.

The event was the culmination of multiple different causes. Although the catalyst for the attack was the dismissal of popular Genevan commoner Jacques Necker (1732-1804) from the ministry of King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792), societal imbalances and financial hardships had been pressuring the French people for years. The perceived efforts of the king to undo the work of the Estates-General of 1789, which had resulted in the formation of a National Assembly dominated by members of the Third Estate, combined with rising bread prices to send the people of Paris into a panic, causing them to lash out against symbols of royal authority, including the ever-looming Bastille.

While the storming of the Bastille was significant in that it saw the first large-scale intervention by the sans-culottes in the Revolution, it was also one of the first instances of bloodshed and mob rule committed by revolutionaries in what had previously been a relatively peaceful and orderly affair. Still, the event marked a major turning point in which the powers of the king were diminished and the process of dismantling the monarchy began.

The Gathering Storm

On the night of 27 June, the skies above Paris were illuminated with fireworks to celebrate the reconciliation of France’s three orders into a single, unified National Assembly. 13 miles away, however, the skies of Versailles remained “mournfully silent” (Schama, 371). Louis XVI, heir to a legacy of absolutism, had been made to suffer the insolence of the Third Estate, who were even now working on a constitution which would strip power out from Versailles and into the hands of the people. The Assembly, which had rebranded itself on 9 July as the National Constituent Assembly, was acting as though it was now in control, something the king could not abide.

On 26 June, Louis XVI called six royal regiments into the Paris region, and on 1 July he summoned ten more. Before long, 30,000 troops were concentrated around Paris, many of them foreign soldiers in the pay of the French monarchy. This ominous build-up was seen by many as the king embarking on counter-revolutionary measures, a warning to the up-jumped members of the Assembly. It was not lost on the Parisians that these foreign troops would likely have fewer scruples firing on Frenchmen than French-born soldiers might have had. On 8 July, an uneasy Assembly formally asked the king to remove the troops, but he refused, declaring that their purpose was only to maintain order in Paris and to protect the proceedings of the Assembly.

At the same time, the king moved against members of his own ministry, dismissing many key figures and replacing them with ministers more hostile to the fledgling Revolution. Jacques Necker, Chief Minister and champion of the Third Estate, was the main target. Blamed by the conservative faction at Versailles for the failings of the Estates-General, Necker received the wrath of the Comte d’Artois, the king’s youngest brother, who referred to him as a “foreign traitor” who should be hanged (Schama, 373). At the urging of Artois and Queen Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), Louis fired Necker on 11 July, ordering him to leave the country immediately. It appeared Louis was tightening the noose on the Assembly and its supporters.

Meanwhile, Paris was already in a state of unrest. A poor harvest followed by a devastating winter meant that bread prices were the highest they had ever been in the 18th century, reaching an all-time high on 14 July. Since bread constituted a significant portion of the average French diet, the poorest workers were forced to spend up to 80% of their income on bread alone. Naturally, angry crowds began to gather. Ordered to disperse one such crowd on 27 June, five companies of the semi-military French Guard mutinied instead. When ten of these guards were imprisoned for indiscipline, 4,000 Parisians invaded the prison and freed them. This unrest, fueled by the presence of royal soldiers, would soon swell into a tempest when news reached the city of Necker’s dismissal.

Riots of 12-13 July

The Palais-Royal, Paris residence of the revolution-sympathizing Duke of Orléans, had become a favorite meeting spot for Parisian revolutionaries. It was here where the outraged masses gathered on 12 July, when word of Necker’s dismissal and exile became public knowledge. Passions were excited, as people carried busts of Necker, with others proceeding to publicly beat a “woman of quality” for spitting on Necker’s portrait. By the afternoon, over 6,000 people had congregated at the palace, looking for somewhere to direct their anger.

A purpose was given to them by 29-year-old journalist Camille Desmoulins (1760-1794). Leaping upon a table in the Café Foy in the gardens of the Palais-Royal, Desmoulins delivered a rousing speech in which he lauded Necker and emphasized the threat of the soldiers, whose oppressive presence could lead to another St. Bartholomew’s Massacre. Brandishing a pistol, Desmoulins issued a call to arms, stating that, “I would rather die than submit to servitude.” (Schama, 382).

With his speech, Desmoulins lit the powder keg of the crowd, which quickly took to the streets. Thousands of Parisians made their way to the Champs-Élysées, alarming royal officials. A cavalry unit, the Royal German regiment, was sent to drive the protestors out of the Place Louis XV (modern Place de la Concorde), pushing them back toward the gardens of the Tuileries Palace. There, Parisians showered cavalrymen with chairs, rocks, and pieces of sculptures, while the soldiers continued to charge, injuring several people. Seeing that the crowds would not back down, the royal commander reluctantly ordered a withdrawal of all troops to the Champ de Mars to avoid a bloodbath.

The next day, with much of the city in the hands of the masses, the true rioting began. Over 40 tollgates were burned, along with the documents and tax records within, and the monastery of Saint-Lazare was pillaged for all its foodstuffs. Fearing imminent retaliation from the king’s soldiers, people began raiding every gunsmith and armory in the city. Although the Hotel de Ville, seat of city government, authorized the formation of a Paris citizens’ militia (later renamed the National Guard) for defense, this did not placate the crowds, who raided the armory at the Invalides on the morning of the 14th, making off with over 30,000 muskets. Lacking ammunition, the crowd looked to a location where they could find some: the fortress of the Bastille.

The Bastille: Symbol of Tyranny

Built in the 14th century to defend Paris against the English, the Bastille was a fortress in every sense of the word. With eight round towers, two drawbridges, and walls eight feet thick, the Bastille loomed over the city as a physical manifestation of the power of the old regime. Converted into a state prison at the start of the 15th century, most of the prisoners kept there had been detained at the express warrant of the king, having been denied judicial process. The prison was famous for its subterranean cells overrun with pests, the horrors of what went on behind its walls were the subject of much gossip. Memoirs by former inmates became popular reading material, enough to frighten any freedom-loving Frenchman.

Yet by 1789, the Bastille was very much a paper tiger. Officials had recently entered talks to close the prison and replace it with a public forum. Although it had been formidable in its past, the Bastille was now considered one of the more desirable places of incarceration for high-born prisoners, with many of its infamous underground cells having fallen into disuse. Many prisoners were allowed beds, tables, and stoves, with one inmate, the infamous libertine writer the Marquis de Sade, permitted the luxuries of a full wardrobe and a 133-volume library. On 14 July 1789, seven people were imprisoned there, including four forgers, an Irish “lunatic”, a deviant young aristocrat imprisoned at the behest of his family, and a man who had conspired to assassinate Louis XV of France over 30 years before.

Still, the idea of the Bastille was more important than its reality. People were still being arbitrarily arrested and hauled off to prisons, a practice symbolized by the fortress. So, although the crowd of roughly 1,000 Parisians arrived before the prison’s walls ostensibly to seize the arms and powder kept there, it was no coincidence that they made for a place as despised as the Bastille.

Storming the Bastille

Bernard-René de Launay, governor of the Bastille, had been born within the very walls that he was now responsible for defending. He had little at his disposal with which to do so: his garrison consisted of 82 invalides, veteran soldiers incapable of serving in the field, as well as 32 Swiss troops who had come as reinforcements. Cannons sat atop the walls, but de Launay only had two days’ supply of food and no water, limiting his ability to withstand a siege. The prize the crowds were after, 250 barrels of gunpowder, sat guarded within.

At 10 AM, as the crowd gathered outside, three delegates from the Hotel de Ville entered the Bastille, asking de Launay to remove the cannon from the walls and hand over the prison’s powder and arms to the custody of the Paris militia. The governor, persuaded by his officers that it would be dishonorable to surrender without direct orders, responded that he could do nothing without permission from Versailles. Having reached an impasse, the delegates left the fortress to ask for further negotiating instructions from their superiors.

Meanwhile, the immense and impatient crowd outside the walls had inched closer, spilling over into the outer courtyard, which was separated by a single wall from the inner, where the real gate of the fortress was located. The wall separating the two courtyards contained a small drawbridge. Half an hour after the Parisian delegates had left, two men climbed the wall and cut the drawbridge’s chains. It fell, killing an unsuspecting man standing beneath. The crowd, believing de Launay had decided to let them in, streamed across by the hundreds. Calls by the soldiers to turn around or be shot were misheard as encouragement to come closer. Before long, someone panicked and a shot rang out, followed by further volleys.

Amidst the chaos, as several revolutionaries fell, people began to accuse de Launay of luring the crowd into the inner courtyard so they could more easily be massacred. Those Parisians with weapons began firing back at the defenders, while carts filled with dung and straw were lit aflame before the gate to provide the attackers with a smoke screen. The fighting intensified, and a delegate waving a white flag of truce was ignored.

Close to 3 PM, the crowd was reinforced by mutinous companies of the French Guard, among them veterans of the American Revolutionary War. Led by Pierre-Augustin Hulin, a former non-commissioned officer, the rebellious soldiers brought up five cannons and took aim at the Bastille’s gate. This was the decisive moment. De Launay, realizing that no royal reinforcements were coming and that the gate could not withstand an artillery assault, offered to capitulate, threatening to ignite the barrels of powder and blow the whole fortress up if his terms were not met. When the crowd refused to accept any terms, de Launay backed down. A white handkerchief was raised above the Bastille in place of a flag of truce, and the second drawbridge was lowered.

The citizen army immediately rushed through the gate, liberating the prisoners, and taking what arms and powder they could find. De Launay’s Swiss soldiers, who had wisely removed their uniforms, were mistaken for prisoners and treated well by the crowd. Many of the invalides were less fortunate. An officer by the name of Béquard had his hand cut off while he was opening the gate to the crowd. Mistaken for a prison warder, the hand was later paraded about the Parisian streets, still gripping the gate key. Later that evening, Béquard was again misidentified, this time for the cannoneer who had fired the first shot, and was hanged.

De Launay, too, would suffer at the hands of the crowd. Believing that he had ordered their massacre, the revolutionaries marched him tto the Hotel de Ville. Along the way, he was insulted and spat upon, with his captors making periodic stops to beat him. Upon arriving at the Hotel, his captors paused to debate the most agonizing methods with which to kill him. When a pastry cook named Desnot suggested bringing him inside before deciding his fate, de Launay, having had enough of the torment, snapped and shouted, “Just let me die!” before kicking Desnot directly in the groin. Immediately, de Launay was met with a shower of daggers, sabers, and bayonets, before the crowd riddled him with pistol shots. After tossing the corpse in the gutter, Desnot leaped upon it and sawed off the head with a pocketknife.

When Jacques de Flesselles, the prévôt des marchands (roughly equivalent to mayor) emerged from the Hotel to see what was causing the commotion, he was shouted down as a traitor and shot dead on the spot. His severed head soon joined de Launay’s on pikes, which were then paraded about Paris by the cheering, laughing, and singing crowds.

82 revolutionaries had been killed during the Storming of the Bastille, with 15 others later dying of their wounds. The event marked the first time that the sans-culottes of Paris had a major impact on the revolution, which was up until this point largely a bourgeoisie affair.

Aftermath

As the famous anecdote goes, when Louis XVI asked if the attack on the Bastille had been a revolt, the Duke de La Rochefoucauld responded, “No, sire, it is a revolution” (Schama, 420). And indeed, it was. The sans-culottes had had their say and refused to be ignored. On 15 July, the king announced the withdrawal of troops from the Paris region, to much applause from the Assembly, and on the 29th, he recalled Necker to serve in his ministry for a third time.

On the evening of the 15th, the king and queen greeted a crowd from atop a balcony in Versailles. The Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) gave a speech in which he assured the crowd that the king had been misled, and that he had meant no ill-will and was returned to full benevolence. That same evening, Lafayette was given command of the National Guard and Jean Sylvain Bailly, orchestrator of the Tennis Court Oath, was made mayor of Paris.

Significantly, neither appointment had been made by the king, who accepted a red and blue revolutionary cockade from Bailly the following day. To symbolize the king’s reconciliation with his people, Lafayette later added Bourbon white to the design, creating the modern French tricolor. Yet it was becoming increasingly clear that Louis XVI was losing power. Unnerved by this thought, the Comte d’Artois stole away from Versailles in the dead of night on 16 July, taking with him an entourage of royalists. Fleeing first to the frontier and then from the country altogether, Artois and his followers would become the first wave of emigres to leave France because of the Revolution.

In Paris, meanwhile, it was decided that the Bastille should be demolished, lest it be reclaimed by royal troops. With the labor of 1,000 workers, the fortress was entirely gone by November. Lafayette would later gift the Bastille’s key to United States President George Washington, who would display it at his home of Mount Vernon.

On 14 July 1790, the first anniversary of the storming was celebrated nationwide as the Fête de la Fédération, with a massive celebration taking place in the spot where the Bastille once stood. Today, 14 July, called the Fête nationale française (French National Celebration), or “Bastille Day” in the English-speaking world, is celebrated on the anniversary of the storming to honor the Revolution, the unity of the French people, and the emergence of democracy in the country.

While the storming of the Bastille was significant for putting power into the hands of the sans-culottes and being one of the first major events of the Revolution, it was also notable for introducing bloodshed into the Revolution. Nine days after the Bastille fell, the deaths of de Launay and de Flesselles were followed by the similar murders of Bertier de Sauvignay, intendant of Paris and Foulon, one of the ministers who was to have replaced Necker’s government. Their heads were stuck on pikes, the mouth of Foulon stuffed with grass to signify his apparent involvement in a famine plot against the people. Even before the introduction of the guillotine and the Reign of Terror, the Revolution had already acquired a taste for blood.

The Storming of the Bastille, therefore, marked both the emergence of liberty in France and the start to the violence for which the French Revolution is so infamous. Due to its monumental importance to the progression of the Revolution, the fall of the Bastille marks a significant place in western history and in the story of the rise of western democracies.