Louis XVI (l. 1754-1793) was the last king of France (r. 1774-1792) before the monarchy was abolished during the French Revolution (1789-99). An indecisive king, his attempts to navigate France through the crises of the 1780s failed, leading to the Revolution, the destruction of the monarchy, and his death by guillotine on 21 January 1793.

Numerous attempts of reconciliation with the budding Revolution failed, and all hope of Louis XVI becoming a dutiful citizen king died after the Flight to Varennes in 1791. Ruling over France first as an absolutist king, then nominally as a constitutional monarch, Louis was finally forced to watch as his people established the First French Republic, and bestowed upon him the humble name of Citizen Louis Capet. He was the only French king to be executed, his death marking the end of a thousand years of uninterrupted French monarchy.

Early Life

The future Louis XVI of France was born on 23 August 1754 as Louis-Auguste de France in the palace of Versailles. He was the son of Louis-Ferdinand, dauphin of France, who himself was the only surviving son of King Louis XV of France (r. 1715-1774). The dauphin had first been married to Infanta Maria-Theresa of Spain, and their marriage was an affectionate one; her death in childbirth at age 20 devastated the dauphin, who was forced to quickly remarry to ensure the family line. In 1747, he took Marie-Josepha of Saxony as a second wife. Although this marriage was relatively loveless, it was fruitful, producing seven children.

Louis-Auguste, given the title Duke of Berry at birth, was the dauphin's third son, although neither of his elder brothers would survive childhood. His birth was followed by that of two younger brothers, Louis-Stanislas, comte de Provence in 1755 (the future Louis XVIII of France) and Charles-Philippe, comte d'Artois in 1757 (the future Charles X of France). The final two children to be added to the dauphin's fast-growing family were Marie-Clotilde in 1759, and Elizabeth-Philippa in 1764.

As a child, Louis-Auguste was strong and healthy. He enjoyed physical sports and often went hunting with his grandfather Louis XV and two younger brothers. He was also rather studious, particularly excelling in his studies of Latin, geography, and history. Yet despite these traits, Louis-Auguste was clearly not cut out to be king. Withdrawn, solitary, and charmless, the young duke of Berry was often overshadowed by his eldest brother, Louis-Joseph, duke of Burgundy, who was already showing signs of possessing the liveliness and charisma needed to be a good ruler. However, Burgundy's death in 1761 at the age of nine thrust Louis-Auguste into the second place in the line of succession. Four years later, his father succumbed to tuberculosis, the same disease that would also take his mother before the end of the decade. Upon his father's death on 20 December 1765, eleven-year-old Louis-Auguste inherited the title of dauphin, becoming heir to the Kingdom of France.

With the absence of a father figure, the responsibility of raising the future king fell to Duke de La Vauguyon. A strict and conservative tutor, Vauguyon's curriculum consisted mainly of religion, morality, and humanities, although he failed to shift the lessons to be more suitable for France's heir. Indeed, some historians credit Vauguyon's tutelage with Louis-Auguste's future indecisiveness as king, as he was taught that timidity was a virtue and that he should never reveal his true thoughts or opinions to others. Louis-Auguste would take this latter piece of advice to heart, leading to much debate over his intelligence level and his actual thoughts about the Revolution.

Marriage & Children

In 1768, to strengthen the new Franco-Austrian alliance, Louis XV arranged for his heir to marry the Austrian archduchess Maria Antonia, youngest daughter of Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa (r. 1740-1780). The wedding was celebrated in Versailles two years later, on 16 May 1770, when Louis-Auguste was 15 and his bride was 14. Despite going by the French version of her name, Marie Antoinette, the French populace would not forget the foreign origins of the new dauphine and referred to her derisively as 'the Austrian woman.' Still shy and awkward, Louis-Auguste was either unwilling or unable to consummate his marriage on his wedding day, a husbandly duty he would not perform for the next seven years. Moreover, the young dauphin often acted coldly towards his wife, preferring horseback rides or solitary hunts to her company. This would cause much grief and embarrassment to the young couple, as their lack of children would lead to ridicule on the part of Louis-Auguste and rumors about Marie Antoinette's faithlessness and sexual depravity.

The childlessness of their marriage has long been the subject of debate. Louis was not impotent, as had originally been thought, nor did he likely suffer from phimosis, a physical condition that would have prevented the act of sex. It was not the fault of Marie Antoinette, who clearly wanted a child. Some historians posit that Louis' self-imposed celibacy was a psychological issue; historian François Furet suggests that Louis XVI was afraid of being controlled and manipulated by his wife the same way his grandfather had been controlled by his various mistresses, most recently the Madame du Barry.

Whatever the reason, the couple only consummated their marriage after Marie Antoinette's brother, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1765-1790), visited Paris incognito in 1777. In a series of letters, Joseph described Louis XVI as "rather weak, but no imbecile," positing that there was "something apathetic in both his body and mind" (Fraser, 156). Describing Louis and Marie Antoinette as "two complete blunderers," Joseph gave the couple advice that appears to have been useful, since the following year both Louis and Marie Antoinette wrote the emperor announcing the queen's pregnancy and thanking him for his help (Fraser, 157).

The couple's first daughter, Marie-Thérèse, was born in 1778. This was followed by the birth of a dauphin, Louis-Joseph, in 1781, and another boy, Louis-Charles, in 1785. A final daughter, Sophie, was born in 1787, although she would live only 11 months. Louis and his wife doted on these children, whose births brought warmth and affection into a previously cold marriage. Still, reputational damage had been done; Louis XVI became the butt of jokes while the queen was accused of being an adulterer, with some going so far as to claim that the royal children were not really the king's. Marie Antoinette would also be accused of being a careless spendthrift and traitorous spy, yet Louis XVI would continue to defend her through major scandals like the affair of the diamond necklace in 1786. The fact that Louis XVI, seen as a moral king, could be married to a woman like Marie Antoinette turned many against him and hastened his downfall.

King of France & Navarre

On 10 May 1774, King Louis XV died at the age of 64. Only 19 years old, Louis-Auguste ascended the throne as Louis XVI, King of France and Navarre. However, along with his grandfather's kingdom, Louis XVI also inherited massive state debt and societal issues that were already eating away at the Ancien Régime's structure. Louis' official coronation at Reims in June 1775 was preceded by a massive wave of bread riots known as the Flour War, a telling portent of what was to come.

The issues facing the country were dire, and France needed the guidance of a strong and steady leader, the type of leader that Louis XVI was not. He came to the throne young and impressionable, lacking both social graces and self-confidence. Already, he was a plump, slow-moving, nearsighted man who enjoyed eating and drinking to excess. He rarely let his true opinions be known, not even in his daily private journals, which resemble ledgers more closely than anything else. Furet notes how Louis XVI's diary is a telling indication of his character, writing that, "this daily diary never betrays the slightest hint of emotion, the least personal commentary: it reveals a soul without strong feelings, a mind sluggish for lack of exercise" (237).

Furet's assessment may be a little harsh, for the king certainly did feel strongly about some things. However, it was usually the things he felt strongest about that contributed to his undoing. For instance, the early part of his reign would be characterized by his strong desire to win the love of his people. For this purpose, he reversed the controversial decision made by his grandfather's chancellor, René Maupeou, and restored power to the parlements, France's 13 judicial courts. Certainly, Louis XVI would have known this decision was unwise since the parlements had been a thorn in Louis XV's side during the final years of his reign, blocking any agenda the old king had tried to put forth. Still, Louis XVI seemed to believe the compromise was worth it to gain his people's love. He thought it was his duty to listen to them; public opinion, he once said, "is never wrong" (Andress, 13).

Louis XVI listened to public opinion again in 1778, when he decided to aid Great Britain's 13 rebellious colonies in North America. Spurred on by a circle of hawkish advisors, Louis XVI became convinced that French involvement in the American Revolution would embarrass Britain and restore to France the prestige it had lost after its defeat in the Seven Years' War. The war was also popular amongst the people, who romanticized America and its plight. Louis' government officially declared war on Britain in March 1778. Although the military endeavor was ultimately successful, it greatly added to the already mountainous pile of state debt, while the success of the Americans further disillusioned many Frenchmen with the idea of despotic monarchy.

Louis XVI patronized the sciences, particularly the aeronautic experiments of Étienne Montgolfier, who amazed a crowd by sending a hot air balloon 18 m (60 ft) above Versailles, carrying a sheep, a duck, and a rooster in its basket. Pilâtre de Rozier would later take off in a balloon from Versailles, and stay airborne for 25 minutes. In 1785, the king's interest in all things nautical led him to commission explorer Jean-François de La Pérouse's circumnavigation of the earth; this same maritime obsession would lead to his visit to the naval port of Cherbourg in 1786, where an expensive harbor was being constructed. Met with great fanfare and shouts of "Vive le roi" ("Long live the king"), Louis would later describe his trip to Cherbourg as one of the only times he was truly happy during his reign. Despite his devout Catholicism, Louis XVI would also pass the Edict of Versailles in 1788. Also known as the Edict of Tolerance, this restored civil rights to French Protestants 102 years after they had been taken away by Louis XIV and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (full freedom of religion would not come until the Revolution).

Decay of Monarchy

By the 1780s, the financial crisis became impossible to ignore. Drawing up a list of financial reforms, Louis' ministers were thwarted by the parlements, who saw an opportunity to regain some of their authority. The Revolt of the Parlements of 1788 helped intertwine French financial difficulties with the mounting social upheaval, as people across the nation called for an Estates-General, the meeting of the three estates of pre-revolutionary France (clergy, nobles, commons). By August, Louis XVI had no choice but to oblige.

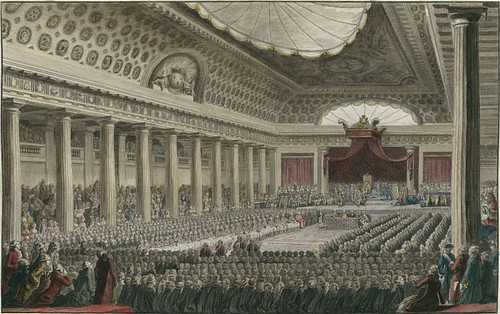

On 5 May, the Estates-General of 1789 met at Versailles, with deputies of all three estates presided over by the popular chief minister, Jacques Necker. However, the meeting was immediately derailed, as the Third Estate refused to call roll until it was assured the three estates would not vote separately, knowing that it would be outvoted by the upper estates on all issues. As the estates stalled, Louis XVI demanded they come to a swift conclusion. However, his attention was called away when his seven-year-old son and heir, Louis-Joseph, suddenly died on 4 June. While Louis was distracted, the Third Estate declared itself a National Assembly and proclaimed all existing taxes to be illegal. After a series of misunderstandings, members of the Assembly took the Tennis Court Oath, swearing not to disband until they had delivered a new constitution to France. The Revolution had begun.

Feeling his power draining through his fingers, Louis XVI decided to act. He ordered 30,000 soldiers into the Paris Basin and fired the royal ministers he felt to be sympathetic to the revolutionaries. One of these was Necker, whose dismissal on 11 July was too much for the people to take. On 14 July, an army of Parisian commons stormed the Bastille, a prison fortress that symbolized the power of the French monarchy. After the Bastille fell, Louis relented, reinstalling Necker and ordering the troops away from Paris before greeting the people from atop a balcony to show his supposed commitment to the revolutionaries' goals. Other royalists were more disturbed by the Storming of the Bastille; on 16 July, Louis' brother Artois fled France along with an entourage of supporters.

The National Assembly was determined to destroy the Ancien Régime and build a new society based on liberty, equality, and fraternity. On the night of 4 August, it drafted the August Decrees, which abolished feudalism; weeks later, it passed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which guaranteed citizens' natural rights; in July 1790, it passed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which subjected the French Catholic Church to the authority of the state. Louis XVI accepted all three of these decrees, albeit against his will. When he had tried to refuse the first two, thousands of Parisian market women and National Guardsmen descended on the palace of Versailles, forcing him and his family to move to Paris, where they were kept as prisoners in all but name in the Tuileries Palace. As the Revolution radicalized, and his position as absolute ruler faltered, even one as indecisive as Louis XVI could realize something had to be done.

Enemy of the Revolution

On the night of 20-21 June 1791, Louis and his family attempted to escape the Tuileries. The king's Flight to Varennes was a failure; although in disguise, Louis was recognized from his portrait on a 50-livre assignat and was escorted back to Paris by the National Guard. This was a watershed moment in the Revolution; prior to this, the king had been looked upon by many as a benevolent king, who was simply being misled by his corrupt ministers. Now, it was clear that Louis XVI himself was hostile to the Revolution, as he had left behind a manifesto condemning the Revolution, its goals, and the constitution. There would be no going back, as people called for his removal, and cries mounted for the creation of a republic.

Throughout the fall and winter of 1791, Louis' position worsened. In September, he consented to the Constitution of 1791 and was officially known by the constitutional monarchist title of "King of the French", rather than his previous absolutist title of "King of France and Navarre". Confined in the Tuileries, he and Marie Antoinette continued to look for salvation from abroad, where his brothers Artois and Provence were rallying an army of emigres, and where Marie Antoinette's brother, Austrian emperor Leopold II (r. 1790-1792) was becoming increasingly hostile to the Revolution. In April 1792, tensions boiled over, as France preemptively declared war on Austria and Prussia, kicking off the French Revolutionary Wars. Louis and Marie Antoinette hoped that the Austrians could prevail and restore them to power.

This hope would be in vain. On 10 August 1792, a crowd of Parisians stormed the Tuileries Palace, driven by fear of the foreign army's threat to destroy the city. Louis XVI was officially arrested three days later and imprisoned with his family in the Temple, the prison fortress where he would spend the rest of his life. On 21 September, the Assembly declared France a republic, and Louis would henceforth be known simply as Citizen Louis Capet. Following the discovery of his private letters in an iron chest, Citizen Capet was put on trial for treason in December and found guilty in January 1793. The Assembly decided on immediate execution; Louis' own cousin was amongst those who voted for death.

Louis said goodbye to his wife and children on the night of 20 January, promising a tearful Marie Antoinette that he would visit them again the following morning. It was a promise he could not bring himself to keep. On the morning of 21 January, the former king received communion at 6 am, asking his valet to give his wedding ring to the queen and the royal signet to his son. He was led to the scaffold on the Place de la Revolution, where he attempted to address the 20,000 people in the square: "I die innocent of all crimes of which I have been charged. I pardon those who have brought about my death and I pray that the blood you are about to shed may never be required of France…"(Schama, 669).

The rest of his speech was drowned out by a sudden drum roll. Louis was then strapped onto a plank and pushed forward beneath the guillotine's blade. After it fell, the executioner lifted the severed head to display it to the cheering crowd, who dipped paper and ribbons in the royal blood as souvenirs. The king was 38 years old, his death a major turning point in the Revolution and the wars to follow.