The involvement of France in the American War of Independence (1775-1783) was not only significant in the progress of the war itself but also as a critical moment for France. Whereas French intervention in the war would help turn the tide in favor of the Americans, the debt it incurred would contribute to the later French Revolution (1789-1799).

Tensions between France and Great Britain had existed for centuries and had only been exacerbated by the recent humiliating defeat of France in the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). A rise in pro-American sentiment combined with nostalgia for the great heroes of French history contributed to the French publics' desire for war, while the government of King Louis XVI (r.1774-1792) saw the war as an ideal way to regain some of the prestige and power lost after France's defeat.

The victory of France and its American allies, solidified with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, reaffirmed France's status as a great military power and saw the independence of the United States. France's involvement heavily damaged its finances, however, a problem that its government proved incapable of solving. Issues that arose from this debt combined with continued state spending were some of the most immediate causes of the French Revolution and the toppling of France's Ancien Régime.

Patriots & Politics

The conclusion of the Seven Years' War in 1763 would have long-reaching ramifications, the ripples of which would affect the rest of the 18th century and, indeed, the course of world history. One of these effects could be seen in the culmination of debt incurred by the British government during the course of winning the war. To pay off this debt, the British Parliament levied a number of different taxes against its thirteen American colonies during the rest of the 1760s and early 1770s. Part of Parliament's rationale in these taxes was that the war had begun in defense of these colonies, who should be made to help pay for its outcome. Resistance of the American populace, particularly its landowning class, to these taxes was a major contributing factor to the outbreak of the American War of Independence in 1775.

A second effect of the end of the Seven Years' War could be seen in France, the vanquished nation. The peace of 1763 had stripped France of much of its North American colonial possessions, most significantly the colony of Canada. Ceding Canada to Britain was not too great of a loss as the colony had become something of a financial burden in recent years, but the damage to France's status and prestige as a great power was a problem. The Seven Years' War had been but the latest conflict in a string of wars fought between France and Britain stretching all the way back to 1689, a series of conflicts referred to by some modern historians as the Second Hundred Years' War (1689-1815). As such, the defeat of France by Britain was especially embarrassing, and many French officials soon started looking for an excuse to get revenge on Britain.

With the ascension of Louis XVI (l. 1754-1793) to the French throne in 1774, this excuse seemed just on the horizon. Tensions between Britain and its thirteen colonies were almost at their boiling point, and many of Louis' ministers wanted in on the coming action. In 1776, as the outbreak of hostilities led to the colonies declaring their independence, the Comte de Vergennes (1719-1787), France's Foreign Secretary, declared that "Providence has marked out this moment for the humiliation of England" and worked to persuade the new king, inexperienced and only 22 years old, to intervene (Doyle, 66).

Although the argument could be made that the hawkish inclinations of men like Vergennes came from a dispassionate, calculated bid for power, the same could not be said for the French populace, many of whom genuinely supported the aims of the American Revolution and desired vengeance against Britain. Many in French aristocratic circles had already viewed America through a romanticized lens, seeing it as a renewed society separated from the cynicism and frailty of the Old World, its settlers possessing the much-admired traits of innocence and freedom. The commitments to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness put forth by Thomas Jefferson (l. 1743-1826) in the Declaration of Independence spoke to the similar Enlightenment ideals that had become so popular in France.

American leaders such as George Washington (l. 1732-1799) were much admired amongst the French, but perhaps no American was as famed as America’s ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin (l. 1706-1790). Playing into the French stereotype that the New World was a place of freedom and innocence, Franklin wore an unostentatious brown coat to court audiences and started to wear a beaver cap. Aware of the hunger for scientific learning amongst the French elite, Franklin leaned into his reputation as a scientific mind, and soon enough his journal, Poor Richard's Almanack, was being translated into French. Franklin's image as the enlightened, educated, and unpretentious American gave the French public exactly what they wanted. At the height of Franklin's celebrity, he could not leave his Paris home without being swarmed by adoring fans, and his likeness, appearing on dolls, snuffboxes, and inkwells, was for a time more recognizable than the king's.

As the War for Independence began, the French began showing their support with engravings commemorating American victories over the British, while French socialites soon began fetishizing the number 13 in solidarity with the 13 colonies; they would meet in groups of 13, each individual wearing an emblem of one of the 13 colonies before drinking 13 toasts to an American victory.

Popular support for the war in France came from a resurgence in its own patriotism. Many in France dealt with the defeat in 1763 by looking nostalgically back to historical French heroes. Figures such as Henry IV of France (r. 1589-1610) and Joan of Arc (1412-1431) were favorites, along with more recent heroes such as the Marquis de Montcalm (1712-1759), who had sacrificed his life fighting the hated British. In the words of scholar Simon Schama, the publication of a historical anthology, the Portraits des Grands Hommes Illustres de la France which celebrated such figures created "a new, exclusively French pantheon of heroes" (Schama, 32). Rising patriotism and anti-British feeling could also be seen on stage; dramatist Pierre de Belloy's 1765 play, The Siege of Calais, depicted French martyrs sacrificing their lives to the wrath of the invading English. This play, casting the English as villains, was immensely popular, attracting 19,000 spectators during its first run.

Despite this fervor for action both by French ministers like Vergennes and the general public, there were still those who thought intervention to be a bad idea. Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot, the French Controller-General, was aware of the burden of debt brought about by France's previous wars and predicted that France could not financially handle another war. In 1776, Turgot denounced Vergennes' planned involvement in America, warning that such a war would permanently destroy any hope of financial reform, predicting that "the first gunshot will drive the state to bankruptcy" (Doyle, 66). Turgot's rather prophetic warnings fell on deaf ears, and he was fired in May 1776.

Aiding the Americans

In 1776, the governing body of the 13 colonies, the Continental Congress, sent Connecticut lawyer Silas Deane to Paris, tasking him with negotiating French support. Deane met with Vergennes, telling him that the Americans had enough men to beat the British in theory but they required ammunition, arms, and money. Seeing this as a relatively low-cost way to fight the British, Vergennes established a private trading company to secretly funnel uniforms, ammunition, and surplus French arms left over from the Seven Years' War to the Americans, in exchange for American products such as tobacco, cotton, and whale oil.

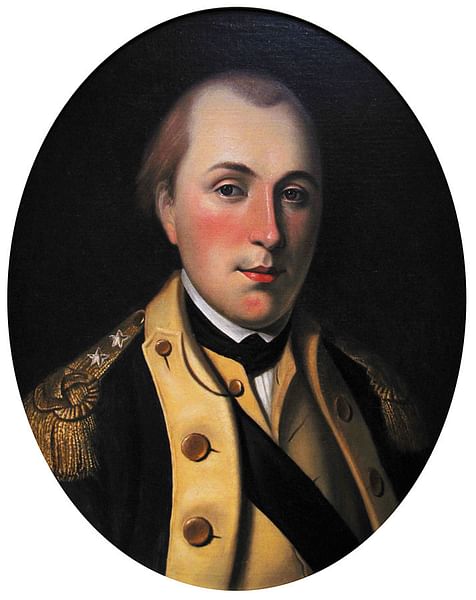

When the Americans under George Washington suffered setbacks at the Battle of Long Island, Congress realized this aid was insufficient and sent Deane back to Vergennes to negotiate a more substantial French alliance. Unable to commit to outright war with Britain, Vergennes agreed to send French officers to train American troops in exchange for these officers to be given high positions in the Continental Army and for a French generalissimo to replace Washington at its head. The man Vergennes had in mind for such a command was Victor-François, 2nd duc de Broglie, who was ordered to come up with a list of officers to present to Deane for consideration in the Continental Army. One of the officers recommended to Deane by de Broglie was a young, ambitious aristocrat, Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (l. 1757-1834).

Vergennes' clandestine scheme to aid the Americans was at first opposed by Louis XVI, who, remembering Turgot's warning, was still reluctant to provoke war with Britain. Vergennes argued that it was France's duty to defeat Britain at all costs, reminding the king that:

England is the natural enemy of France…The invariable and most cherished purpose in her politics has been, if not the destruction of France, at least her overthrow, her humiliation, her ruin…All means to reduce the power and greatness of England…are just, legitimate and even necessary. (Unger, 19)

The king was persuaded by his minister's words and changed course, approving the scheme, but Vergennes' plan would soon be thwarted when it was discovered by British agents. When threatened with war should the French officers be allowed to depart for the Americas, Louis XVI backed down. Despite the king's subsequent decree forbidding any French officer from adventuring in the Americas on penalty of imprisonment, Lafayette sneaked out of France aboard the ship Victoire. Upon arriving in the colonies, Lafayette was given the rank of major general in the Continental Army, achieving fame through his battlefield exploits and becoming one of Washington's right-hand men. Other French officers would follow suit, although Vergennes' plot to replace Washington with de Broglie would ultimately never materialize, as Washington quickly regained his popularity.

The heroics of Lafayette, the public desire for war, and the persuasion of men like Franklin and Vergennes soon pushed Louis XVI closer to favoring war. When news came of the Americans' astounding victory at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, a renewed enthusiasm for the American Revolution swelled in France, and Louis finally gave Vergennes permission to negotiate a military alliance with the Americans.

The Bourbon War

Having finally achieved his goal of embroiling France in the American War, Vergennes sprung to action. On 6 February 1778, France recognized the independence of the United States and entered a Treaty of Alliance with it. Crafting an alliance with the Spanish Bourbons and the Dutch Republic, Vergennes presented Britain as an aggressor, declaring that this new coalition was only intervening to preserve the Americans' independence. By March, France and Britain were officially at war. Although part of the American War for Independence, the specific conflict between Britain and France during this time also became known as the Anglo-French War of 1778 or alternatively as the Bourbon War.

The early years of France's involvement in the war proved unsuccessful. A fleet commanded by the Comte d'Estaing arrived off British-controlled New York in summer 1778 but was unable to enter the harbor and attack the city. D'Estaing then sailed toward Newport, Rhode Island, hoping to combine with the Americans and take the city. The attack failed due to a combination of poor weather and the lack of cooperation between French and American soldiers. D'Estaing returned the next year, this time moving against British-controlled Savannah, Georgia. After an unsuccessful naval bombardment, d'Estaing launched a ground assault, which also was repelled. The same year, the planned invasion of mainland Britain, involving a 30,000-man army commanded by Lafayette that was to be ferried across the English Channel by an armada of Spanish ships, was foiled by the outbreak of smallpox amongst the Spanish crews, stormy weather, and a British flotilla that moved to guard the Channel.

The situation improved markedly in 1780 when 6,000 French soldiers under the command of the Comte de Rochambeau landed in Rhode Island. Unlike d'Estaing, who refused to take orders from the Americans on account of his nobility, Rochambeau put his aristocratic feelings aside and deferred to the command of General Washington. After an American army under the command of Lafayette trapped a larger British army in the port village of Yorktown, Washington and Rochambeau worked together to press their advantage; while Washington moved in by land to reinforce Lafayette, a French navy cut the British off by the sea. The surrender of this British army in October 1781 was the decisive moment that effectively brought the war in North America to an end.

The North American theater proved to be one of many, however, as the entry of France, Spain, and the Netherlands enlarged the war to a global scale. On 24 June 1779, the combined Bourbon armies of France and Spain besieged the British at Gibraltar. The siege would continue long after the North American theater was decided at Yorktown, with the final large-scale assault on Gibraltar not coming until September 1782. The siege was not lifted until February 1783.

The war was also carried into the Caribbean and into India, where the two great powers still had colonies. Following the victory at Yorktown, the French navy captured Dominica, Grenada, Saint Vincent, and Tobago in the West Indies before finally being stopped by a British fleet at the Battle of the Saintes in April 1782. This naval battle was considered Britain's greatest victory over the French during the war. In India, the conflict between Britain and France caused the British to go after France's ally, the Kingdom of Mysore, sparking the Second Anglo-Mysore War in 1778. The Siege of Cuddalore, beginning in July 1783, was one of the last actions of the war and ended only when preliminary talks of peace were announced.

As the conflict dragged on in many different parts of the world, the need for more funds grew increasingly vital. It fell to Jacques Necker (l. 1732-1804), a Genevan banker who had been named Louis XVI's Director of the Treasury in 1776, to procure these funds. Determined not to increase taxes, Necker financed France's intervention in the war through loans. Between 1777 and his resignation in 1781, Necker raised 520 million livres in loans, piling even more debt on a state that already had debt in abundance. After his resignation, his successor, Joly de Fleury, felt obliged to raise the taxes and raised 232 million more livres. By the end of the war in September 1783, France had spent over 1.6 billion livres fighting the British.

Aftermath

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 did not see any of the lands taken in the 1763 peace returned to France. All territories captured in the War of Independence were returned to their original owners, with the exception of Tobago and part of the Senegal River area, which France kept. Spain regained Florida and Minorca, although Gibraltar remained under British control. The United States, of course, had their independence recognized and officially became a nation.

For all intents and purposes, it appeared that France had achieved everything it had set out to do. It had both embarrassed Britain and deprived it of the 13 colonies, while simultaneously regaining its status as a formidable power. King Louis XVI, impressed with the performance of the French navy during the war, continued the financing of the military port at Cherbourg, which could theoretically provide a base for a future invasion of Britain. This would prove an expensive endeavor that would amount to very little payoff.

Regarding France itself, the legacy of its intervention in the American Revolutionary War was one of massive debt. Necker's policy of not raising taxes may have endeared him to the public, but it did nothing to alleviate the state's financial burden. In fact, Necker had gone so far as to publish an account of France's finances in February 1781, known as the Compte rendu au roi (report to the king), in which he reported that ordinary revenues were exceeding expenditure by over 10 million livres. However, Necker's report did not include the extraordinary accounts, which contained the real cost of the war. Had this figure been published, it would have shown France in a significant deficit.

The American Revolution also continued to endear itself in the minds of members of the French public. Many in France still saw the revolution as a manifestation of Enlightenment ideals. Patriotism in France had already been on the rise before the American Revolution, but the success of such an enterprise came as proof that change was indeed possible.

Without French support, it is doubtful that the Americans could have prevailed against Britain. Yet, the impacts of the war on France were almost entirely negative; despite regaining some prestige and glory, France did not weaken Britain nearly as much as it had wanted to and put itself over 1 billion livres deeper in debt than it previously had been. The war and the spending that accompanied it would prove to be fatal to the French monarchy; less than six years after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, the continual downward spiral of French finances would lead to the beginning of the French Revolution.