James Armistead Lafayette (l. c. 1748-1832) was an African American Patriot who served the Continental Army as a spy during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). During the Siege of Yorktown, he infiltrated the British camp to bring crucial intelligence to the Americans. After the war, he was freed from slavery with the help of the Marquis de Lafayette, whose name he adopted.

Early Life

James Armistead Lafayette was born into slavery around the year 1748 in New Kent County, Virginia (some sources give his birth year as 1760). He was born on the property of Colonel John Armistead, and became the colonel's slave; although later writers and historians would refer to him as James 'Armistead', he never adopted his master's surname during his lifetime and was instead simply referred to as 'James'. James was raised alongside Colonel Armistead's son, William, with the intention that James would eventually serve as William's personal manservant. For this purpose, James was given a basic education and was taught how to read and write, skills unusual for enslaved persons in Colonial America, but which James needed to know to be an effective servant. When William Armistead came of age, the colonel gifted him James as his manservant, with William inheriting the rest of his father's slaves and lands when the colonel died in 1779.

James likely would have remained a manservant for the rest of his life, fading into historical obscurity in much the same way that most of the other 450,000 enslaved individuals living in the Thirteen Colonies at the time did. However, in 1779, the same year that Colonel Armistead died, something happened that would change the course of James' life forever: the American War of Independence came to the south. By this point, the war was well into its fourth year; the United States of America had declared its independence, the decisive Battles of Saratoga had been fought in New York, the Continental Army had reorganized itself at Valley Forge, and the Kingdom of France had entered the war on the American side. But up until now, most of the fighting had taken place in the north, particularly in New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania; the British had been focused on seizing key American cities like Philadelphia and New York City, while simultaneously isolating New England, believed to be the heart of the American rebellion.

But after the failure of several northern campaigns, the British turned their focus to the southern states, which were rumored to be replete with Loyalists eagerly awaiting the return of royal authority. The British implemented their southern strategy, capturing Savannah, Georgia, in December 1778 and laying siege to Charleston, South Carolina, in early 1780. With the arrival of the redcoats on their shores, southern colonists were forced to choose where their loyalties lie; this included the tens of thousands of African Americans, such as James, who had to decide whether the Patriots or the Tories (Loyalists) offered the better chance at freedom.

Black Loyalists & Black Patriots

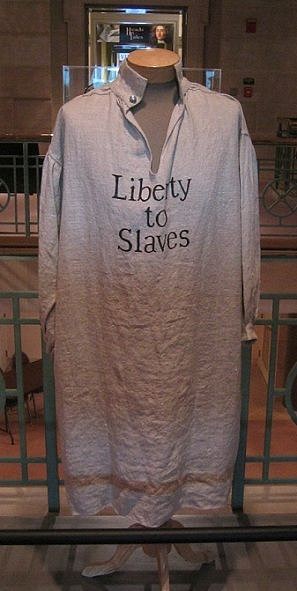

In November 1775, only a few months after the war had begun, the royalist governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation in which he promised freedom to any enslaved man who took up arms against the Patriots. Thousands of Black men from across the south traveled to Norfolk, Virginia, to answer Dunmore's call and fight for the British; many of these former slaves were organized into an all-Black Loyalist military unit, called Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment. The regiment seemed enticing, offering liberty, adventure, and a chance at heroism to men who had spent their entire lives performing forced labor for the benefit of their White owners. To underscore this point, the uniforms of the Ethiopian Regiment were even inscribed with the words "Liberty to Slaves". However, before the regiment could see any major battles, large numbers of its troops were incapacitated or killed by a bout of smallpox that ravaged the unit in the winter of 1775-76. Though the Ethiopian Regiment was disbanded in the summer of 1776, many Black Loyalists continued to aid the British war effort, still hoping to win their freedoms; perhaps the best example of this was the Black Brigade, an all-Black Loyalist militia led by a former slave named Colonel Tye, that ravaged the Patriot-controlled countryside of Monmouth County, New Jersey, in 1780.

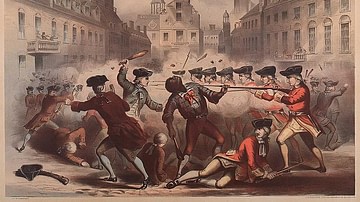

Although many African Americans fought for the Loyalist cause, there were many more who fought for the fledgling United States. Black Patriots had existed for about as long as the Patriot movement itself; in fact, one of the first casualties of the American Revolution was a mixed-race Black and Native American man named Crispus Attucks, who was one of the victims of the Boston Massacre (5 March 1770) and was afterwards hailed as a martyr for the cause of American liberty. Five years later, a slave named Prince Estabrook was one of the 77 Patriot militiamen to stand up to over 700 British regulars on Lexington Green; Estabrook was wounded in the ensuing fight, known as the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April 1775), but recovered in time to guard the headquarters of the Continental Army during the Siege of Boston. Another enslaved militiaman, Salem Poor, would distinguish himself during the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775). After most other American militiamen had already fled from the redoubt on Breed's Hill, Poor had remained behind to help evacuate the wounded. As the British stormed the American redoubt, Poor fired the shot that allegedly killed Lieutenant Colonel James Abercrombie, a British officer leading the charge.

By the time the Revolutionary War came to Virginia, therefore, there were thousands of Blacks serving with valor and distinction on both sides of the conflict, all of them believing that their side was their best chance at securing their freedom. By 1781, James had not yet chosen a side; he had not heeded Lord Dunmore's call for Black Loyalists, nor had he gone off to fight in the Continental Army, which had begun officially recruiting Black soldiers in 1778, offering enslaved men freedom in exchange for military service. Instead, James had remained as the personal manservant of William Armistead, who himself was an ardent Virginian Patriot. When James heard that the French general Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, was looking specifically to recruit African American men to aid the Patriot cause, James asked his master for permission to serve. William Armistead agreed on the condition that James remain his slave when his service was over.

Spying for the Patriots

At this point in the war, General Lafayette was leading a detachment of American troops in pursuit of a British army led by Benedict Arnold, who had once been an American general before famously turning coat and going over to the British. Lafayette had been ordered by George Washington to capture Arnold and hang him as a traitor. To achieve this mission, Lafayette hoped to gather intelligence as to Arnold's intentions and troop numbers; the best way to do this was to use African Americans as spies, under the pretext that they were runaway slaves looking to join the British to secure their freedom, as was still guaranteed by the Dunmore Proclamation.

It was in this capacity that James was used when he joined Lafayette in early 1781. Posing as a runaway slave, James made his way to Arnold's camp in Portsmouth, Virginia, where he pledged his services to the British. James, who knew the local territory quite well, was able to gain Arnold's trust by guiding British troops through the surrounding lands; Arnold, thinking in much the same way that Lafayette had been, also decided to use James as a spy, and sent him back to the American camp to gather intelligence. It was in this manner that James became a double agent, moving back and forth between the American and British camps. He would gather intelligence from the British camp to bring back to Lafayette, while simultaneously feeding false information to Arnold's officers. It was a dangerous game; since James was a spy and not an enlisted soldier, he was not protected by the rules of war that governed the fates of soldiers who were captured in battle. Like the famous Nathan Hale before him, James was liable to be hanged if the British ever discovered that he was secretly working for the Americans. James, however, proved to be a rather successful spy; using the intelligence brought to them by James, Washington and Lafayette were able to prevent 10,000 British reinforcements from linking up with the main British army in Virginia, led by Lord Charles Cornwallis.

After Arnold departed Virginia and headed back north, James stayed behind and served as an ostensible 'courier' for Lord Cornwallis. In this capacity, he was able to overhear conversations between British officers and read letters entrusted to him by Cornwallis' staff; since he was a slave, few expected that James knew how to read and write, which greatly aided his effectiveness as a spy. He continued providing the Continental Army with intelligence from Cornwallis' headquarters during the Siege of Yorktown (28 September to 19 October 1781), with his espionage work helping to lead to the ultimate American victory in the siege. With the surrender of Lord Cornwallis' army at Yorktown, the last major engagement of the Revolutionary War was over; two years later, the Treaty of Paris was signed, officially ending the war. The last British troops evacuated from the United States in November 1783, taking thousands of refugee Black Loyalists with them.

Emancipation

After the war, the US Congress freed those enslaved men who had served in the Continental Army. This did not apply to James, however, since he had served as a spy and had never been enlisted as a soldier. Instead, James returned to his old master, William Armistead, to resume his duties as an enslaved servant. This did not stop him from petitioning the Virginia Assembly for his freedom, however, as he argued that he had provided the United States with as much service – and had risked his life just as much – as men like Prince Estabrook and Salem Poor who had fought on the Revolution's battlefields and had won their freedoms. But since he was not a soldier, James' first petition was denied.

In 1784, Lafayette learned that James was still enslaved; remembering the services that James had done for the American cause, the marquis agreed to meet with James in Richmond, Virginia. There, Lafayette provided James with a written testimonial in which he praised the services that James had rendered to the new republic. The marquis attested that James had done:

essential service to me while I had the honor to command in this state [of Virginia]. His intelligence from the enemy's camp were industriously collected and most faithfully delivered. He perfectly acquitted himself with some important commissions I gave him and appears to me entitled to every reward his situation can admit of (Unger, 200).

Armed with Lafayette's testimonial, James again petitioned the government of Virginia for his liberty. This time, he was aided by his master, William Armistead, who had won a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates in 1786. Both houses of the Virginia legislature voted to accept James' petition, which was signed by the governor of Virginia on 9 January 1787; James was finally freed, with Armistead being financially compensated for the loss of his slave. Upon securing his freedom, James adopted the surname 'Lafayette' to show his gratitude to the French general.

Later Life

After winning his freedom, James Lafayette moved 9 miles (15 km) south of New Kent County, where he purchased 40 acres (16 ha) of land and started a farm. He married and raised a large family, although he did not receive the military pension owed to him by Congress until 1819, 27 years after the war had ended. After many years of petitioning Congress for the money owed to him, he was finally granted an annual pension of $40, as well as $60 in back pay.

In 1824, nearly 50 years after the start of the War of Independence, President James Monroe invited the aged Marquis de Lafayette on a tour of the United States. The marquis, who had not been in America for decades, happily accepted, visiting each of the 24 states where he was cheered by ecstatic crowds of Americans who hoped to catch a glimpse of one of the Revolution's last surviving heroes. When the marquis was visiting Yorktown, Virginia, he heard someone call out his name; looking into the crowd, the marquis saw the familiar face of James Lafayette, whom he recognized immediately. The Marquis de Lafayette then leaped off his horse, rushed into the crowd, and embraced the former spy to the applause of the gathered throngs of Virginians.

James Lafayette died in either 1830 or 1832 when he would have been around 80 years old. His long life was certainly an extraordinary one: born into slavery, he risked his life spying for the Americans, helping to bring about the final American victory at Yorktown. He then entered into another kind of battle – a legal one – in which, with the help of the Marquis de Lafayette, he won his freedom. Certainly, James Lafayette is an often overlooked figure who deserves mention as one of the notable figures of the Revolutionary War.