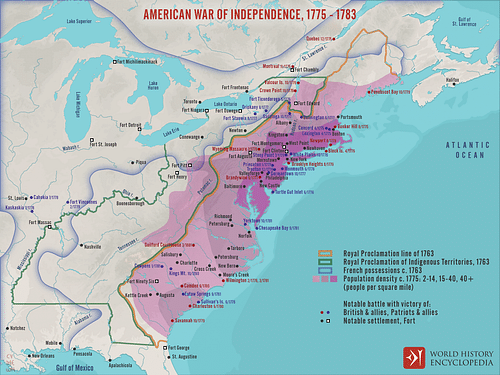

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were engagements fought between British regular soldiers and militia from the colony of Massachusetts on 19 April 1775. The British troops were on their way to seize military supplies stored in the town of Concord when they were confronted by the colonial militiamen. An American victory, the battles triggered the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

The battles were the culmination of a decade-long struggle between the British Parliament and the Thirteen Colonies of British North America over the issue of American rights and the idea of 'no taxation without representation'. Beginning in 1764, Parliament had attempted to impose several taxes on the colonies, including the Sugar Act (1764), Stamp Act (1765), and Townshend Acts (1767-1768). Each of these acts had been vehemently resisted in the colonies, on the basis that, since the Americans were unrepresented in Parliament, Parliament had no power to directly tax them. Incidents such as the Boston Massacre (5 March 1770) and the Boston Tea Party (16 December 1773) only deepened the rift between the mother country and her children; hoping to restore order, particularly in the impertinent Province of Massachusetts Bay, Parliament enacted the Intolerable Acts in 1774, which, among other things, closed Boston's port to commerce and replaced several of the colony's elected officials with royal appointees.

This was too much for the colonists to stomach. In September 1774, delegates from twelve of the Thirteen Colonies gathered at the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia to discuss a potential boycott of British imports. While there, the delegates approved the Suffolk Resolves, a measure that called for the local militias of Massachusetts to prepare to defend the colony's liberties. Tensions between the colony's Patriot and Loyalist factions increased over the winter, as British troops routinely marched into the Massachusetts countryside looking to confiscate weapons and ammunition from the militias. On 19 April 1775, a column of British troops set out to seize Patriot munitions stored in the town of Concord. On the way, they were confronted by roughly 70 American militiamen on Lexington Green; after a brief standoff, someone fired a shot, leading the soldiers to fire two volleys into the militia, killing eight and wounding ten.

The British continued on to Concord, only to find that most of the supplies had been moved or destroyed. Meanwhile, the British covering force at Concord's North Bridge was engaged by around 400 militiamen, and the soldiers were forced to withdraw. During their retreat to Boston, the British soldiers were harassed by a steadily growing number of New England militiamen, who took shots at the regulars from behind barns, trees, and stonewalls. When the British finally reached the safety of Boston, as many as 15,000 colonial militiamen waited outside the town, ready to begin the Siege of Boston (19 April 1775 to 17 March 1776). The Battles of Lexington and Concord, the first shot of which would later be described by Ralph Waldo Emerson as 'the shot heard round the world', led to the Revolutionary War and the independence of the United States of America, becoming one of the key moments of the broader American Revolution (c. 1765-1789).

Prelude

By late 1774, tensions were climbing in and around Boston, the capital of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. As punishment for the many transgressions Boston had committed against Parliamentary authority, including the recent Boston Tea Party, the British Parliament had closed the town's port to commerce, installed a military governor in Massachusetts, and replaced the colony's elected council with royal appointees. These policies, collectively known in the colonies as the 'Intolerable Acts', were egregious enough for colonial Patriots who feared for their liberties but were also disastrous for the town's merchants and dock workers.

The situation worsened when regiments of the British regular army arrived in Boston for the first time since the Boston Massacre; the sight of redcoats once again drilling on Boston Common and standing guard on King Street reopened old wounds. In September 1774, as the Continental Congress gathered in Philadelphia to discuss a unified colonial response to the Intolerable Acts, several Massachusetts Patriots convened to pass the Suffolk Resolves, which, among other things, called on the colony's local militias to begin preparing for a potential conflict with the British soldiers. Many of these militiamen were eager for a fight, with some firebrands even urging all of Boston's Patriots to evacuate the town so that they could burn Boston to the ground with the Loyalists and soldiers trapped inside. The proverbial powder keg was set and needed only a spark to explode.

General Thomas Gage, the recently appointed military governor of Massachusetts, was determined to snuff out this spark before it could even be lit. A naturally affable man with an American-born wife, Gage had initially hoped to restore royal authority in the colony without resorting to violence. However, his attempts to enforce the Intolerable Acts were frustrated by the colonists, while many of the men who had received royal appointments to the governor's council were intimidated into resignation by the Patriots. In a report to the king's ministers, Gage suggested that the Intolerable Acts should be repealed; if this could not be done, he requested reinforcements, believing he could not crush a rebellion with less than 20,000 troops (he currently only had 3,000 in Boston). As he waited for a reply, Gage decided that his best course of action was to postpone a conflict by seizing the arms and ammunition that could be used by Patriot militias. On 1 September 1774, Gage sent 260 regulars to seize the gunpowder stored in a magazine in modern Somerville, northwest of Boston. Although this was accomplished without incident, rumors were spread that the redcoats had murdered six men in the process, leading thousands of colonial militiamen to descend on Cambridge. Actual bloodshed was averted only when the militiamen learned that the rumors had been false.

This event, known as the Powder Alarm, woke Gage up to the reality that he was not dealing with a "rude rabble" confined to Boston, as the king's ministers had asserted, but a burgeoning political movement that was rapidly spreading throughout the Massachusetts countryside (Middlekauff, 272). As Gage spent the winter fortifying Boston Neck, a so-called Provincial Congress met in the town of Concord; presided over by John Hancock and consisting of many of Massachusetts' leading Patriots, the Congress was meant to serve as the provisional government of the colony should war break out. Luckily for Gage, the Congress knew it could not strike first; to do so would be to risk losing the support of the other twelve colonies, who would only come to Massachusetts' aid in the event of a defensive war. Thus, the standoff between the militia and redcoats continued into the new year, as Gage nervously awaited instructions to arrive from London.

The Expedition

As early as November 1774, King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) had written Prime Minister Lord North that "the New England governments are in a state of rebellion, blows must decide whether they are subjected to this country or independent" (Middlekauff, 268). Parliament shared the king's bellicose opinion, with both houses voting in February 1775 to proclaim Massachusetts to be in a state of open rebellion. It is hardly surprising, then, that the king's ministers brushed off Gage's suggestion to repeal the Intolerable Acts, as well as his request for more troops; surely, they believed, the backwoods rabble-rousers of Massachusetts could easily be crushed with the troops Gage had at his disposal. Lord Dartmouth, secretary of state for the colonies, stated as much in his instructions to Gage, which arrived in Boston on 14 April 1775. Admonishing Gage's inactivity, Dartmouth urged the general to act decisively and suggested the arrests of the members of the Provincial Congress. Such an action would undoubtedly lead to war, but Dartmouth argued that it was better for a conflict to begin now than to wait for the colonies to attain "a riper state of rebellion" (Middlekauff, 272).

These instructions, although in Dartmouth's words, were implied to have come directly from the king. Gage could not afford to dither any longer, but the leaders of the Provincial Congress were outside his reach, and Gage knew he could not arrest them without alerting the entire colony. Instead, he opted to seize the arms and ammunition widely known to be stored in the town of Concord, which included four brass cannons, two mortars, and ten tons of lead balls. Beginning on 15 April, Gage discreetly detached 700 elite troops from their regiments for the expedition to Concord; these included roughly 400 grenadiers and a slightly smaller number of agile light infantrymen. Major John Pitcairn of the Royal Marines would lead the light infantry, while command of the entire expedition was given to Colonel Francis Smith. To explain the sudden concentration of elite British troops, Gage announced that they would be headed into the countryside for training exercises.

Yet Gage was not being as discreet as he thought. Before even Colonel Smith's troops knew their true intentions, half of Boston was aware that the munitions in Concord were in danger. Rumors even began to circulate that John Hancock and Samuel Adams, who were staying in the town of Lexington on the route to Concord, were the true targets of the expedition. Hancock was considered the face of Massachusetts' Patriot movement while Adams was thought to be the brains; their arrests would be a considerable blow. On 16 April, Dr. Joseph Warren, one of Boston's leading Patriots, dispatched silversmith Paul Revere to Lexington to warn Hancock and Adams. On his way back to Boston that night, Revere stopped in Charlestown to arrange a signal for when the British were on the move: if the troops were to move by land over Boston Neck, one lantern was to be hanged, two if they came by sea (the signal was immortalized in Longfellow's poem as 'one if by land, two if by sea').

Lexington Green

At around 10 p.m. on the night of 18 April 1775, the troops selected for Colonel Smith's expedition were quietly woken by their sergeants. Rubbing the sleep from their eyes, the troops were quietly rowed to Lechmere Point in East Cambridge, where they waded ashore to wait along a road for their instructions. These instructions did not come until 2 a.m., at which point the regulars waded across Willis Creek; Colonel Smith avoided the bridge to not alert the colonists by the sound of the soldiers' footfalls. The colonial militias, however, had already been roused. Dr. Warren had sent Revere and another rider, William Dawes, along the two best-travelled roads to Concord to alert the towns. After evading two British officers on the road, Revere arrived in Lexington close to midnight, while the regulars were still waiting for orders in East Cambridge. When the silversmith approached the house where Hancock and Adams were staying, he was reprimanded by a militiaman for making too much noise. "Noise!" Revere responded. "You'll have noise enough before long! The regulars are coming out" (Philbrick, 238).

Revere convinced Hancock and Adams to flee Lexington for their own safety, while approximately 130 of the town's militia gathered on Lexington Green. The militia was commanded by Captain John Parker, a veteran of the French and Indian War, who was already suffering from the tuberculosis bout that would soon kill him; the other men were all neighbors and extended family members, who knew and trusted one another. It was a bitterly cold morning, and as they waited for the regulars, some of the militiamen returned home to warm up with the understanding that they would reform on the Green once the troops had arrived. Having successfully done their duty, Revere, Dawes, and a third man named Dr. Samuel Prescott mounted up and rode to Concord. Along the way, Revere was captured by a group of British officers but was eventually released and made his way back to Lexington on foot. It was not until 4:30 a.m. when the first elements of Major Pitcairn's scarlet-coated light infantrymen entered Lexington. With muskets loaded, the regulars formed into battle lines opposite Captain Parker's militiamen, of whom only 70 had returned. Pitcairn and several mounted officers rode ahead of their troops, yelling at the colonists to "throw down your arms, ye villains, ye rebels! Damn you, disperse!" (Philbrick, 252).

Captain Parker had initially told his men, "Stand your ground. Don't fire unless fired upon. But if they want to have a war, let it begin here" (Philbrick, 251). Outnumbered and staring down the barrels of British muskets, Parker decided it was best to let the regulars pass and ordered his men to disperse. Some of the militiamen obeyed this command, others held their ground. Before long, a shot rang out; it is unknown which side fired it, but it was a shot long remembered as 'the shot heard round the world'. A series of disjointed crackles were heard as the light infantrymen fired a volley, without orders; some of the militia initially thought the troops were firing blanks to intimidate them until their comrades started crumpling to the ground around them. Several militiamen returned fire as the regulars unleashed a second, more coordinated volley. When the smoke cleared, eight militiamen were lying dead on Lexington Green, with ten more wounded. The only British casualty was an infantryman whose leg was grazed by a bullet.

Concord & Menotomy

Once the Lexington militia had scattered, the British troops let out three cheers and continued along the road to Concord, fifes and drums blaring; the skirmish at Lexington had negated the need for discretion. But William Dawes, who escaped from the officers who had captured Revere, arrived in Concord in time to warn them of the regulars; the town's ringing bell attracted companies of minutemen, highly mobile militia who were trained to be combat-ready at a minute's notice. By the time Colonel Smith's force arrived at around 7 a.m., militiamen from surrounding towns had long been filtering into Concord.

The militiamen initially offered no resistance as the regulars progressed over the North Bridge toward Colonel James Barrett's house, where the munitions were rumored to be stored. Smith posted three companies of light infantry to guard the North Bridge, while his grenadiers raided Barrett's house and the surrounding buildings. Aside from some bags of flour and 500 pounds of musket balls, the soldiers found nothing of value; at some point during their search, the blacksmith shop and courthouse caught on fire, though it is unknown if this was intentional. The militiamen, whose numbers had swollen to over 400, were enraged when they saw the flames from atop nearby Punkatasset Hill. Many of them descended the hill and made their way to the North Bridge, where they encountered the three companies of light infantry. After exchanging some insults, the British opened fire, killing two Americans and wounding a third. At this, militia Major John Buttrick cried, "For God's sake, fire!" (Philbrick, 281). The colonists' answering volley left three British privates dead, and nine more soldiers wounded.

The regulars, shocked, soon broke ranks and fled. The Americans, perhaps equally shocked and flooded with adrenaline, pursued. Despite the confusion, Colonel Smith was able to gather his troops and, at noon, commenced an 'orderly' retreat to Boston. The British were able to make it unmolested for about a mile before the American militiamen were able to launch an attack. But when the attacks came, they were devastating; all along the twelve-mile road back to Boston, British soldiers came under fire from the Americans who took cover behind trees, barns, fences, and stonewalls. The British returned fire when they could, unleashing deadly volleys whenever they were able to pin the militiamen against the road. However, the number of militiamen continued to grow, leaving the British on the verge of panic by the time they returned to Lexington. At 2:30 p.m., as Smith reformed his shaken troops on Lexington Green, he was joined by about 1,000 reinforcements under Earl Hugh Percy; Smith's troops were able to take an hour of much-needed rest as Percy's artillery kept the Americans at bay.

At around 3:30 p.m., Earl Percy led the British column out of Lexington and on toward the town of Menotomy (modern-day Arlington), where the regulars were set upon by as many as 5,100 militiamen; fresh companies from surrounding towns had joined those who had been pursuing the British since Concord. The fighting in Menotomy turned particularly bloody, as homeowners took shots at British troops from within their houses, leading to barbaric hand-to-hand combat. Percy soon lost control of his men, who were fueled by fear and rage to pillage the Menotomy houses and attack the civilians inside. It was only with great difficulty that Percy's officers restrained their men from killing every civilian they found. Once order had been restored, the British resumed their bloody journey to Boston.

Aftermath

Percy's ragged force only escaped danger once it reached Charlestown after sunset. Throughout the day's fighting, the British suffered 273 casualties while the Americans lost 95 dead and wounded. The Americans, who had demonstrated that they were more than capable of standing up to British regulars, were determined to follow up on their victory. By the next morning, over 15,000 militiamen from across New England had surrounded Boston and began to lay siege; these militiamen would form the basis of the American Continental Army. The Battles of Lexington and Concord, therefore, had been a dramatic start to the eight-year-long war that would ultimately result in the independence of the United States of America.