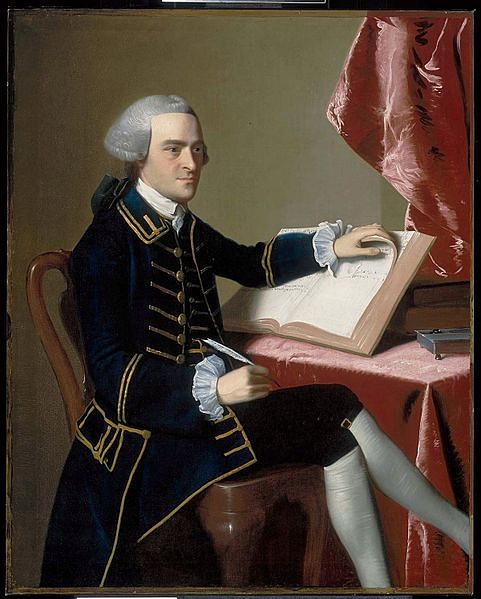

John Hancock (1737-1793) was a merchant, politician, and Founding Father of the United States, who helped lead the Patriot movement during the American Revolution (1765-1789). He served as president of the Second Continental Congress from 1775-1777, as governor of Massachusetts from 1780-1785 and again from 1787-1793. He is best remembered for his flamboyant signature on the Declaration of Independence.

Early Life

John Hancock was born on 23 January 1737 in Braintree, Massachusetts (modern-day Quincy). He was the second of three children born to Reverend John Hancock and Mary Hawke Hancock; he had an elder sister, Mary (b. 1735) and a younger brother, Ebenezer (b. 1741). John Hancock's childhood was a solitary one. His father was often preoccupied with the spiritual needs of the community while his mother preferred doting on his elder sister, leaving John to his own devices. He took to following around the older boys of Braintree, which included John Adams and Samuel Quincy; although the older lads tolerated Hancock's presence, they did not like the younger boy, whom Adams later described as possessing "a peevishness that sometimes disgusted and afflicted his friends" (Unger, 15).

In 1744, Reverend Hancock died after a brief illness at the age of 41. Faced with the impending horrors of poverty, Mary Hawke Hancock appealed to her late husband's brother, Thomas, for help. From humble beginnings as a bookseller's apprentice, Thomas Hancock had become one of the most successful merchants in Boston, having founded a world-famous firm called the House of Hancock. There was, however, a small problem threatening Thomas' commercial empire: he had no heir. He and his wife Lydia had been unable to have children. So, when his brother's widow reached out for help, Thomas decided to cut a deal. He agreed to financially support Mary and her children, on the condition that John be sent to live with him in Boston, to be groomed to one day inherit the Hancock family business.

Mary agreed, and John was sent to live in his uncle's lavish house atop Beacon Hill. The Hancock home was a three-story, Georgian-style mansion, made of square-cut granite blocks, with a superb view of Boston Harbor. The reverend's son would have marveled at the delicately imported mahogany furniture, beautiful oil paintings, and apricot trees imported from Spain. He was carefully tutored to fit the part of an elegant Boston gentleman, was taught etiquette and introduced to members of Boston's high society. He was dressed by his doting aunt in velvet breeches and silk coats, sparking a lifelong love affair with expensive clothing. In 1750, he was enrolled in Harvard at the age of 13, the second youngest in his class. During his college days, he regularly got into trouble; he drank frequently and, at one point, got the enslaved servant of the Harvard president dangerously drunk. Still, he managed to graduate in July 1754 (albeit without academic honors). Now 17, Hancock was tall, slender, and sophisticated, always dressed in the most fashionable clothes. It was time for him to learn the family business.

Merchant King

Immediately after John's graduation, Thomas began to prepare his nephew for an eventual partnership. He had John shadow him on all his business dealings, telling the young man to carefully observe every meeting and dinner discussion. It was an interesting time for John to be thrust into the world of commerce, as the French and Indian War (1754-1763) was rapidly escalating, creating a high demand for war supplies in the colonies. Thomas Hancock, with the kind of prescience only a savvy and cutthroat businessman could have, had anticipated the outbreak of hostilities and had spent the previous years stockpiling his warehouses with weapons and ammunition; he quickly made a fortune selling these supplies to the British army and the colonial militias, and by 1758, the House of Hancock had become the primary financier for the British war effort in North America. The Hancocks lent their small fleet of merchant ships to the British military, helping to transport troops and, on a darker note, with the forced removal of the French Arcadians from Canada.

Toward the end of the war, John Hancock was sent to London to establish closer ties with the family's agents there. But Hancock, dandy that he was, could not resist reveling in the extravagant lifestyle of London high society; during his year-long trip, he spent over £500, which, as one biographer points out, was five times more than most skilled craftsmen made in a year (Unger, 56). But the party came to an end in October 1761, when Thomas Hancock's failing health precipitated John's return to Boston. As Thomas' condition worsened, John took over the day-to-day business operations; he purchased the remaining shares of Clark's Wharf, quickly renamed Hancock's Wharf, and focused on cornering the lucrative whale oil market. On 1 August 1764, Thomas Hancock collapsed from a stroke and died shortly afterward. John inherited not only the House of Hancock and its associated businesses but also his uncle's mansion on Beacon Hill; at only 27 years old, Hancock was now one of the wealthiest men in America.

From Merchant to Patriot

The end of the Seven Years' War in 1763 coincided with an economic depression in the Thirteen Colonies. Many smaller merchant companies folded beneath the financial pressure and even businesses as large as the House of Hancock were struggling; "trade has met with a most prodigious shock," Hancock wrote to his London agents in 1765, "times are very bad and precarious here" (Unger, 71). It was at this moment of economic hardship that the British Parliament, eager to pay off its mountainous war debt, voted to levy a series of taxes on the colonies. The first sign of trouble was the Sugar Act, passed in 1764 with the intention of collecting revenue from the molasses trade. Colonial merchants like Hancock had previously avoided sugar taxes by smuggling in molasses from the French and Dutch West Indies and bribing customs officials to look the other way; since molasses was integral to the economy of the New England colonies, most Americans regarded the smuggling as a victimless crime. With the Sugar Act, Parliament cracked down on smuggling operations and stipulated that merchants could only purchase molasses from British-owned plantations, which were far less productive.

The Sugar Act dealt a blow to Hancock's business. By May 1765, he was over £9,000 in debt, and the next tax policy passed by Parliament did not seem likely to aid his financial situation. The Stamp Act, which placed a tax on all paper documents, was widely opposed by colonists for a multitude of reasons. For Hancock, whose business dealings relied on the signing of many contracts, each of which was now susceptible to the tax, it was a financial burden he could ill afford. He wrote to his representative in London, asking him to lobby to repeal the Stamp Act, which he referred to as "very cruel" (Unger, 88). Around this time, opposition to Parliament's taxes had led to a frenzy of resistance in Boston; mobs of Bostonians, led by an underground group known as the Sons of Liberty, had ransacked the homes of several prominent officials in August 1765. Although Hancock also detested the tax, he was nervous that the fury of the mob would soon be turned against him as one of Boston's wealthiest citizens.

Hancock's fear of mobs and his desire to protect his business interests drove him to seek refuge with Samuel Adams, one of the intellectual leaders of the Patriot movement in New England. Adams had long been preaching to his fellow colonists that the Parliamentary taxes were a violation of their rights; since the Americans were unrepresented in Parliament, Parliament had no authority to directly tax them. To accept these unjust taxes, Adams warned, would be for the colonists to subject themselves to the state of "tributary slaves" (Schiff, 73). Hancock soon became something of a protégé to Adams. While some biographers have accused Adams of manipulating Hancock in the same manner that "the Devil is represented seducing Eve" (Unger, 95), it was, in reality a symbiotic relationship; Adams' words reached a larger audience coming from the lips of one of Boston's wealthiest and most influential men, while Hancock enjoyed protection from the mobs and could claim the moral high ground in defending his business interests from Parliament's taxes.

Hancock quickly became the face of the Patriot movement in New England and was perfectly suited to the role. He was already well-liked amongst Boston's working class; hundreds of Bostonians worked for him and regarded him as a generous boss. When a fire destroyed twenty houses in 1767, Hancock contributed to the relief fund and oversaw the distribution of firewood to the city's poor. He was also quite the showman, ensuring that news of the repeal of the Stamp Act arrived in Boston aboard one of his own ships, and setting out casks of Madeira wine on Boston Common so the city could celebrate. When Parliament passed yet another tax policy, the Townshend Acts, Hancock urged Massachusetts' merchants to boycott British goods and pushed a resolution through the Massachusetts assembly urging colonists to make their own goods to reduce dependence on Britain.

The Liberty Affair

As Hancock's profile as Patriot leader continued to grow, he made some powerful enemies. In November 1767, when five British tax commissioners arrived in Boston to enforce the Townshend Acts, Hancock refused to speak or even shake hands with them at the docks. This show of disdain led to the commissioners' ostracization from Boston high society; Hancock was the city's most eligible bachelor, and the Boston elite did not want to risk offending him by inviting the commissioners to dinners. So, when the Customs Board decided it needed to make an example out of a leading Patriot figure, it naturally targeted Hancock.

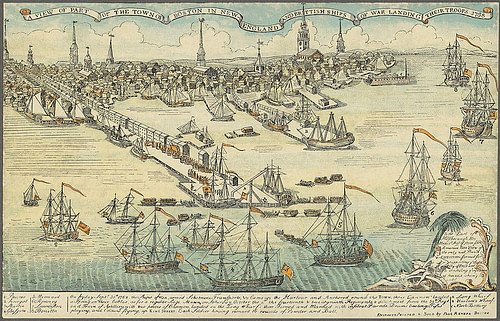

On 9 May 1768, one of Hancock's sloops, the Liberty, arrived in Boston Harbor carrying crates of Madeira wine. Two customs officials inspected the ship the following morning and passed it; however, a month later, one of the inspectors changed his story, alleging that the Liberty had been carrying smuggled cargo and that he had been forcibly detained below decks while the ship's crew had unloaded it. This was enough of a pretext for the Customs Board to seize the Liberty and, on 10 June, the warship HMS Romney prepared to tow it away. The Bostonians were already angry with the Royal Navy for impressing dock workers, and the sight of the Romney seizing an American ship proved too much to bear. An altercation between Bostonians and British sailors soon erupted into a city-wide riot, forcing the tax commissioners to flee to Castle William in Boston Harbor for their own safety.

Hancock was then prosecuted in a highly publicized trial before a Vice-Admiralty court, represented by his childhood companion John Adams. Hancock managed to get the charges dropped after dragging the proceedings out for five months; but this small victory for the Patriots was overshadowed when, on 1 October 1768, two regiments of British soldiers arrived in Boston to restore order after the Liberty riots. Tensions between the soldiers and colonists escalated, culminating in the Boston Massacre (5 March 1770). After the massacre, Hancock led a committee demanding the withdrawal of British troops from the city, which was done shortly thereafter. Although he did not take part in the Boston Tea Party (16 December 1773), he voiced his approval, condemning anyone who supported the British Tea Tax as an 'enemy of America'.

A Hunted Man

In 1774, Parliament passed the so-called Intolerable Acts to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party. These included the closure of Boston Harbor, the suspension of representative government in Massachusetts, the return of British soldiers to Boston, and the installation of General Thomas Gage as military governor. In response, Massachusetts Patriots formed a revolutionary government called the Provincial Congress that met in the town of Concord. Hancock was elected its president and helped the colony's militias prepare for a potential conflict. He also served as one of Massachusetts' delegates to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, where it was decided to boycott British goods until the Intolerable Acts were repealed.

In early 1775, rumors began to circulate that General Gage meant to arrest Hancock and Samuel Adams for their leadership in the illegal Provincial Congress; instead of risking a return to Boston, therefore, Hancock and Adams stayed in Hancock's childhood home in the town of Lexington, on the road to Concord. In the early morning hours of 19 April 1775, Hancock and Adams were awoken by Paul Revere, a member of the Sons of Liberty who came bearing news that British regulars were marching toward Lexington. Fearing that the soldiers were coming to arrest them, Hancock and Adams fled, making their escape mere hours before the Battles of Lexington and Concord kicked off the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). The two men made their way to Philadelphia to take their seats in the Second Continental Congress; on 24 May 1775, Hancock was unanimously elected president of the Congress.

Political Career

Hancock oversaw the creation of the Continental Army, as well as the appointment of George Washington as its commander-in-chief. When Congress had its first recess in August, he married his fiancée, Dorothy Quincy Hancock in Fairfield, Connecticut; tragically, neither of the couple's two children would survive to adulthood. After his hasty marriage, Hancock returned to Philadelphia and presided over the debate for independence. He was the first to sign the Declaration of Independence when it was adopted on 4 July 1776; his large, flourishing signature became so famous that, in the United States, the phrase "John Hancock" is a colloquialism meant to refer to one's signature.

During Hancock's time as president, Congress was forced to evacuate Philadelphia twice; the first evacuation occurred in late 1776 when Washington was nearly defeated in the New York and New Jersey Campaign, and the second came a year later when the British briefly occupied Philadelphia. In both instances, Washington ultimately prevailed, allowing Congress to return to the capital. Despite such uncertainties, Hancock worked tirelessly to provide the Continental Army with recruits, money, and resources. In October 1777, Hancock resigned from Congress. By this point, he had fallen out with Samuel Adams, who believed that Hancock's vanity and ostentatiousness were inconsistent with republican principles. Hancock returned to Boston and, hoping to win some military glory, led 6,000 militiamen to partake in the Siege of Newport, Rhode Island, in the summer of 1778. The ensuing Battle of Rhode Island (29 August) ended in disappointment for the Americans, putting an end to Hancock's brief military career.

Hancock returned to politics in October 1780, when he was elected the first governor of Massachusetts, winning 90% of the vote. He continued to govern Massachusetts until the end of the war, at which point he remained popular even though his state was experiencing economic troubles. Hancock, however, anticipated that these economic issues would worsen before they got better, leading to his preemptive resignation in January 1785; this crisis would ultimately lead to Shays' Rebellion (1786-87), which was left to Hancock's successor to deal with. In 1787, after the uprising was suppressed, Hancock returned to the governorship and was continually re-elected for the rest of his life. In between his two tenures as governor, he was once again elected president of Congress. However, his gout prevented him from making the trip to New York City to take up his office, leading him to resign from Congress in 1786.

Later Life

In 1787, Hancock experienced tragedy when his nine-year-old son, John George Washington Hancock, died from a head injury obtained while ice skating. By this point, Hancock's own health was deteriorating, as he was constantly afflicted by gout and other illnesses. When the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention drafted a new US Constitution in September 1787, Hancock greeted the news with skepticism; the Constitution, which would place greater power in the hands of the federal government, lacked a Bill of Rights to safeguard American liberties. He presided over Massachusetts' ratification convention in 1788, staying silent throughout much of the debate. However, when it seemed as though ratification might fail, Hancock rose and gave a speech in favor of the Constitution. Thanks in part to his speech, the committee approved the Constitution by a narrow margin, 187 to 167. In 1791, a Bill of Rights was finally added to the Constitution, easing Hancock's initial concerns.

Hancock was a contender for the first US presidential election of 1789; though it was obvious that Washington would become president, the office of vice president was up for grabs, leading Hancock to quietly campaign for the position. The office ultimately went to John Adams, and Hancock remained governor of Massachusetts. His ill health meant that his cabinet members looked after issues of governance as Hancock spent more time confined to bed in his Beacon Hill mansion. On 8 October 1793, John Hancock died at the age of 56. Samuel Adams, succeeding him as governor, gave his old friend an extravagant state funeral, which may have been the largest funeral given to any American up until that point.

Shortly after his death, Hancock disappeared from the pantheon of American Revolutionary heroes; indeed, his Beacon Hill mansion was torn down in 1863. He was criticized by several historians for his vanity and lust for popularity, with many doubting his Patriotic sentiment. However, because of his leadership during the American Revolution, he undoubtedly deserves to be in the same conversation as the other recognized founders of the United States.