The Second Continental Congress was the body of delegates that governed the Thirteen Colonies and, later, the United States during the American Revolutionary War. Between its first session in May 1775 and its disbandment in March 1781, the Congress oversaw the war effort, adopted the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation, and secured an alliance with France.

The First Congress

The quarrel between Great Britain and its 13 North American colonies began in the mid-1760s with the passage of the Sugar Act (1764), Stamp Act (1765), and Townshend Acts (1767-68). These policies, passed by the British Parliament, placed direct taxes on the American colonies, each one considered more egregious than the last; the Stamp Act, for instance, put a tax on all paper documents such as legal contracts, newspapers, and playing cards, while the Townshend Acts included taxes on items such as glass, paint, paper, and tea. The colonists protested these taxes on the basis that they violated their 'rights as Englishmen'. The British constitution, they argued, guaranteed the right of self-taxation for all the king's subjects. Since the colonists were unrepresented in Parliament, any attempt by Parliament to tax them violated this right. Parliament responded to this concern by passing the Declaratory Act in 1766, proclaiming that it had the right to legislate on behalf of the colonies "in all Cases whatsoever" (Middlekauff, 118).

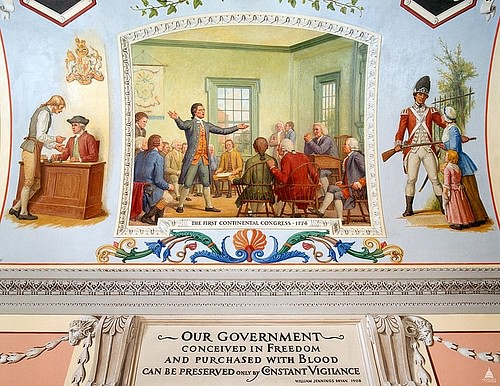

Rising tensions led to riots in the colonies, particularly in the town of Boston, Massachusetts, where a group of rabble-rousers known as the Sons of Liberty targeted tax officials and other royal representatives. In 1768, Parliament dispatched soldiers to Boston to restore order, ultimately resulting in the Boston Massacre (5 March 1770), when nine British soldiers fired on a crowd of Bostonian protestors, killing five. The situation escalated further on 16 December 1773, when the Sons of Liberty boarded three merchant ships tied up in Boston Harbor and dumped 342 chests of British East India Company tea into the water, in protest of Parliament's tea tax. The Boston Tea Party enraged Parliament, which decided to punish the insolent colonies with a series of retributive policies later known as the Intolerable Acts. This included the closure of Boston Harbor and the restriction of self-governance in the colony of Massachusetts, among other things. The other colonies voiced their solidarity with Massachusetts, viewing the Intolerable Acts as an attack against their collective constitutional rights; in September 1774, delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies gathered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for the First Continental Congress to coordinate a response.

The First Congress sat for nearly two months. Its first act, after electing Peyton Randolph of Virginia as its president, was to accept the Suffolk Resolves, which allowed the New England militias to begin preparing for war with the British soldiers. Next, the Congress agreed to boycott British goods until the Intolerable Acts were revoked, and some delegates drafted petitions to King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) and the British people, explaining their grievances. The First Congress disbanded on 26 October 1774 with the understanding that if the situation did not improve, its members would reconvene the following May. Indeed, the situation continued to deteriorate; by the time the Second Continental Congress convened at State Hall (later Independence Hall) in Philadelphia, the Battles of Lexington and Concord had been fought, and the American Revolutionary War had begun.

A Wartime Government

At the outbreak of the war, the Second Continental Congress was the only assembly keeping the Thirteen Colonies united, leading it to assume the responsibilities of a provisional, wartime government. But before it could direct the war effort, it needed a president; on 10 May 1775, Peyton Randolph was re-elected to fill that position, but illness forced him to step down two weeks later. He was replaced by John Hancock, the wealthy merchant from Boston who had long been recognized as the face of the Patriot movement. The Irish-born Charles Thomson of Pennsylvania was confirmed as the Continental Congress' secretary, a position he held for the Congress' entire existence. The rest of the Congress was, initially, made up of 56 delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies; Georgia, which had not sent any delegates to the First Congress, did not send delegates to the Second until July 1775, at which point the number of congressmen rose to around 60. The individual delegates who sat in the Congress fluctuated over the course of its existence, as certain members were voted in and out, died, or left on their own accord; however, the number of delegates sitting at any given time usually hovered around 60. In all, 342 individuals served in the Continental Congress and its successor, the Congress of the Confederation, between 1774 and 1789.

Once the president and secretary were confirmed, the Second Continental Congress turned its attention to the war. By this point (May 1775), the Siege of Boston was underway; nearly 15,000 New England militiamen had trapped an army of British regulars in Boston. On 15 May, Congress passed a resolve that put the rest of the colonies in a state of military readiness, asking them to prepare their own militias for conflict. At the same time, it raised several rifle companies from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, to supplement the New England army outside Boston. In June, Congress 'adopted' the New England army, which was reorganized as the Continental Army. Virginian aristocrat George Washington, whose experience in the French and Indian War (1754-1763) rendered him one of the most experienced army officers in the colonies, was appointed to head a committee to draw up the rules and regulations that would govern Congress' new army. On 15 June, Washington was appointed as the commander-in-chief of that army; four major generals and eight brigadier generals were selected to act as his subordinates.

On 22 June, Congress voted to issue $2,000,000 worth of bills to finance the war, beginning production of the ill-fated Continental currency of paper notes. Paul Revere engraved the plates for the initial bills, and Congress created the Bank of North America in Philadelphia to print them. In October, Congress also approved the creation of a Continental Navy and, two months later, authorized the construction of 13 frigates.

Meanwhile, as Congress desperately tried to create something resembling a war ministry from scratch, the war itself continued to escalate. Outside Boston, the bloody Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June) was fought, while news soon reached Philadelphia that the Americans had captured Fort Ticonderoga in New York (10 May). News of these successes emboldened Congress to officially invite the British Province of Quebec (Canada) to join the rebellion as the 14th colony, referring to the Canadians as "fellow-sufferers" of British tyranny (Middlekauff, 286). When the Canadians failed to respond, Congress authorized the American invasion of Quebec; although the invasion ultimately met with defeat, it brought into question Congress' insistence that it was fighting a purely defensive war.

Many delegates believed that reconciliation with Britain was still possible. On 5 June 1775, Congress adopted the Olive Branch Petition. The petition, penned by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, affirmed the colonists' desire to remain faithful subjects of the king and expressed their wish to find a peaceful solution to the problems created by Parliament. The Olive Branch Petition was made to appear just a touch disingenuous, however, when Congress adopted the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, in which the colonists explained why it had become necessary to fight against Britain. Thomas Jefferson, allegedly, wrote a first draft that was deemed too radical, leading Congress to appoint Dickinson to write a more moderate version. This declaration, as well as the news of Bunker Hill, led King George III to reject the Olive Branch Petition out of hand; instead, the king issued the Proclamation of Rebellion, in which he formally declared the Thirteen Colonies to be in a state of rebellion against the Crown. Afterward, no further attempts were made by Congress to reconcile with Britain.

Declaring Independence

By December 1775, the Americans had learned that the king had condemned them as rebels and that more British troops were on the way to oppress them. While total independence from Britain had been unthinkable even a month earlier, many colonists came to terms with the fact that it may be their only remaining course of action. In January 1776, the public desire for independence was inflamed by Thomas Paine's seminal pamphlet Common Sense, which offered several arguments for cutting ties with the British Crown and concluded with the statement that: "Reconciliation is now a fallacious dream" (Middlekauff, 325). Within Congress itself, a faction led by the Adamses of Massachusetts and the Lees of Virginia began to lobby the other delegates for independence. One of their arguments was that the European powers, particularly France, would not consider aiding the rebellion militarily unless the colonies became independent from the British Empire first.

In the spring of 1776, the Congress began to prime the colonies for independence. In early April, after heated debate, Congress voted to open colonial trade to the entire world except Britain. Then, on 10 May, it passed a resolution suggesting that any colony with a government that did not favor independence should form one that did. Five days later, it attached a preamble to this resolution, written by John Adams, calling for each colonial government to officially renounce its allegiances to the British Crown. Certainly, there was still a faction within Congress that resisted these steps toward independence, but it was quickly shrinking as the Adams-Lee independence faction gained momentum. On 7 June 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia proposed a motion that:

these United Colonies are, and of right out to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved (Middlekauff, 331).

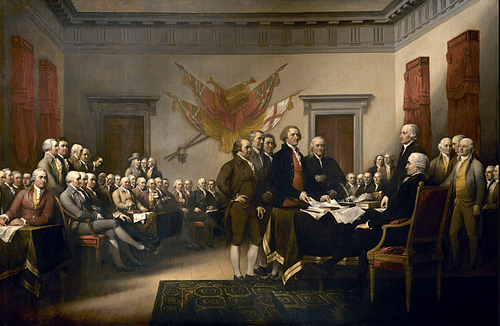

Lee's motion was debated over the course of the next two days; some delegates thought it was too soon to declare independence, believing that the middle colonies were "not yet ripe for bidding adieu to the British connection", while the Adams-Lee faction disagreed, arguing that the people were anxiously waiting "for us to lead the way" (ibid). Congress ultimately decided to postpone the vote until 1 July; in the meantime, a committee was put together to compose a declaration of independence, should Lee's motion carry. The committee was comprised of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert R. Livingston, and Thomas Jefferson, with Jefferson doing most of the writing. The committee finished its work on 28 June; by then all colonial governments except New York had authorized their congressional delegates to approve independence. On 1 July, the vote for independence carried by a large majority, and the Declaration of Independence was adopted on 4 July. The United States of America was born.

Overseeing the War

Upon declaring independence, the Continental Congress assumed the position of the provisional government of the United States, but it soon seemed that Congress' status as the government of an independent nation would not last for long. In August 1776, the British defeated Washington's army at the Battle of Long Island and occupied New York City several weeks later. On 11 September, a congressional delegation met with the British on Staten Island to discuss terms for peace, but talks quickly broke down once the British demanded a renunciation of independence as a prerequisite for negotiation. The British army, under Sir William Howe, proceeded to chase the Continental Army through New Jersey; disease, desertion, and the expiration of enlistments reduced the American army to less than 3,000 men by December. Congress, fearful that the British army was too close, evacuated Philadelphia for the safer location of Baltimore, Maryland.

Washington, realizing he did not have enough men, asked Congress to raise more battalions. Congress agreed, issuing a resolve on 27 December 1776 that invested Washington with the "full, ample, and complete powers to raise and collect together…from any or all of these United States, sixteen battalions of infantry" as well as to "displace and appoint all officers under the rank of brigadier general", to take "whatever he may want for the use of the army, if the inhabitants will not sell it", and to arrest all persons who remained "disaffected to the American cause" (Boatner, 1170-71). Many viewed this as Congress bestowing Washington with dictatorial powers, although it allowed Washington to build his army more freely without having to constantly appeal to Congress. That winter, Washington won two important victories at the Battle of Trenton (26 December) and the Battle of Princeton (3 January 1777), allowing Congress to return to Philadelphia.

In September 1777, Congress was once again forced to evacuate Philadelphia when it was captured by the British; Congress took up residency in York, Pennsylvania, where it remained until the British evacuated Philadelphia in June 1778. During this time, Congress blamed Washington for the recent defeats; several delegates conspired to replace Washington with General Horatio Gates, a scheme that became known as the Conway Cabal. Washington, however, was able to win enough support in Congress to defeat the vote to replace him.

Articles of Confederation

Meanwhile, Congress had dispatched several commissioners to Europe to secure foreign aid, including Arthur Lee, Silas Deane, and Benjamin Franklin. These commissioners were easily able to obtain financial aid from the Kingdom of France; hoping to get revenge on Britain for France's defeat in the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), Comte de Vergennes, the French foreign minister, secretly supplied the Americans with money, weapons, and officers to train their troops. Once the Americans triumphed over a British army at the Battles of Saratoga (autumn, 1777), France entered negotiations with Congress about a potential alliance. Congress ratified the French alliance on 4 May 1778, and France entered the war.

Around the same time, Congress passed the Articles of Confederation on 15 November 1777, after over a year of debate, and sent it on to the states for ratification. Meant to serve as a constitution for the new country, the Articles established a weak central government in order to preserve the sovereignty of the states. Congress, as it waited for the states to approve the Articles, used it as the basis for all foreign policy and legislation that it conducted. However, the states themselves did not quickly ratify the Articles; one of the major concerns was that the Articles would leave the smaller states powerless against the tyranny of larger states. By February 1779, twelve of the thirteen states had ratified the Articles, with Maryland as the sole holdout.

Congress, in the meantime, was facing a new set of problems. Its currency, the 'Continental', had quickly depreciated in value; by January 1779, it had dropped to 90% below face value, leading to widespread inflation. As a result, Continental soldiers became frustrated with their pay, which was often backed up to begin with, and citizens preferred to sell their goods to the British for real hard currency rather than to the Americans for the worthless 'Continentals'. Indeed, the phrase 'not worth a Continental' became a commonplace saying (Boatner, 275). In 1781, the Continental currency was discontinued. Congress also had to deal with a series of defeats in the South such as the Siege of Charleston (29 March to 12 May 1780) and the Battle of Camden (16 August 1780). Once Congress' own choice for the southern command, Horatio Gates, was defeated, Congress allowed Washington to select a replacement; Washington's choice, General Nathanael Greene, proved more successful.

Disbandment

In February 1781, Maryland finally ratified the Articles of Confederation, which went into effect on 1 March. The Second Continental Congress was therefore disbanded and replaced by the Congress of the Confederation, which governed the United States under the Articles. Later that year, Washington forced the surrender of Lord Charles Cornwallis' British army at the Siege of Yorktown (28 September to 19 October 1781), ending the active phase of the Revolutionary War. On 3 September 1783, the war was officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which was ratified by Congress in January 1784.

The Congress of the Confederation continued to operate as the legislative body of the United States. It was, essentially, a continuation of the Second Continental Congress; it was a unicameral assembly that acted with both legislative and executive powers. In 1787, however, issues with the Articles of Confederation led to the United States Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, where it was decided to replace the Articles with the Constitution of the United States. The Constitution went into effect on 4 March 1789 after being ratified by the states, and the Congress of the Confederation was disbanded. It was replaced by the Congress of the United States, a bicameral body consisting of a House of Representatives and a Senate, with only legislative functions. This version of Congress remains in use today, as the legislative branch of the United States federal government. But certainly, modern Congress owes its existence to the Second Continental Congress which, despite its many faults, governed the United States during one of its most uncertain times.