The Conway Cabal was a movement undertaken by American military officers and political leaders to remove General George Washington from command of the Continental Army during the winter of 1777-78. These Patriot leaders had lost confidence in Washington's cautious style of leadership and plotted to replace him with the more energetic General Horatio Gates, hero of Saratoga.

The so-called 'cabal' centered around the New Englanders in Congress who were both frustrated by Washington's lack of boldness on campaign and fearful that the Virginian general was growing too powerful. It was not a 'cabal' or 'conspiracy' in the strictest sense of those words, but rather a loose network of disgruntled Patriot leaders who preferred Gates' leadership to Washington's; this network included Samuel Adams, Thomas Mifflin, Dr. Benjamin Rush, and, of course, Brigadier General Thomas Conway, after whom the 'cabal' was named. In November 1777, Washington was made aware of a letter written by Conway that disparaged him, leading the general to suspect a plot to replace him with Gates. Washington's generals and political allies responded by announcing their support of the commander-in-chief, thwarting any plans to replace him. The 'cabal' then unraveled as Conway resigned and Gates issued an apology. The Conway Cabal was the only serious political threat Washington faced during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

Reasons for Discontent

There were several reasons why prominent Patriot leaders became frustrated with, or in some cases suspicious of, Washington's leadership. The primary reason rested in Washington's insistence on waging the war with a Fabian strategy. Named after the ancient Roman dictator Quintus Fabius Maximus, who employed such tactics against the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca, the Fabian strategy advocates for the avoidance of major pitched battles in favor of wearing down the enemy through attrition and small skirmishes. This style of fighting appealed to Washington, who was opposed by one of the best-trained militaries in the world and was aware that the destruction of his army would most likely spell the end to the American Revolution and kill all chances of an independent United States.

For these reasons, Washington prioritized the preservation of his army over the glory of battlefield victories. Especially after the stinging American defeat at the Battle of Long Island (27 August 1776), Washington preferred to retreat whenever the odds were stacked against him, attacking only when an opportunity presented itself; this combination of retreat and attack proved fruitful in late 1776 when Washington was able to surprise and defeat a German garrison at the Battle of Trenton. Washington's Fabian tactics were not appreciated by everyone; indeed, many congressmen were frustrated by Washington's reluctance to fight major battles, blaming the general's leadership style for the loss of important cities like New York and Philadelphia. Washington's strategy was certainly working – the prolonged war was becoming less popular in England, while frustrated British field commanders began to bicker amongst themselves – but was not enough for those Patriot leaders who sought a single decisive battle to win the war.

Another reason for the discontent was a fear that Washington was growing too powerful. By 1777, he was already lionized by the American public, who revered him as a savior. John Adams, who believed such hero worship to be incompatible with the ideals of the revolution, wrote a letter in which he grumbled, "the people of America have been guilty of idolatry in making a man [Washington] their God" (Boatner, 278). Men like Adams would have grown increasingly disturbed in late 1776, when the Second Continental Congress voted to give Washington near-dictatorial powers in order to prosecute the war. These powers included the ability to recruit soldiers from any state, the authority to dismiss officers at will, and the power to jail enemies of the revolution. This horrified many in Congress, particularly the New Englanders, who were already skeptical of a standing army and preferred to rely on militias. The idea of a popular commander-in-chief, already regarded as a hero by the masses, with near-dictatorial powers at the head of a standing army conjured up images of an American Oliver Cromwell or Julius Caesar. By 1777, men like John Adams, Samuel Adams, and Richard Henry Lee were searching for ways to bring the army back under tight congressional control.

The final major reason for the Conway Cabal rested in Washington's military failures during the Philadelphia Campaign of 1777. On 25 August, a British army had landed at Head of Elk, Maryland, with the intention of marching on the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia. Washington, forced to abandon his Fabian strategy to defend the seat of Congress, met the British at the Battle of Brandywine (11 September) and was defeated, though he succeeded in extricating his army before it could be decisively destroyed. The British then outmaneuvered Washington and captured Philadelphia, which Congress had only recently evacuated; Washington's attempt to retake the city was thwarted at the Battle of Germantown (4 October), and the campaign season ended with two of North America's most valuable cities, Philadelphia and New York, under British control. As Washington moved his army into winter quarters at Valley Forge, some members of Congress – temporarily located in the town of York, Pennsylvania – began to search for candidates for his replacement.

The Hero of Saratoga

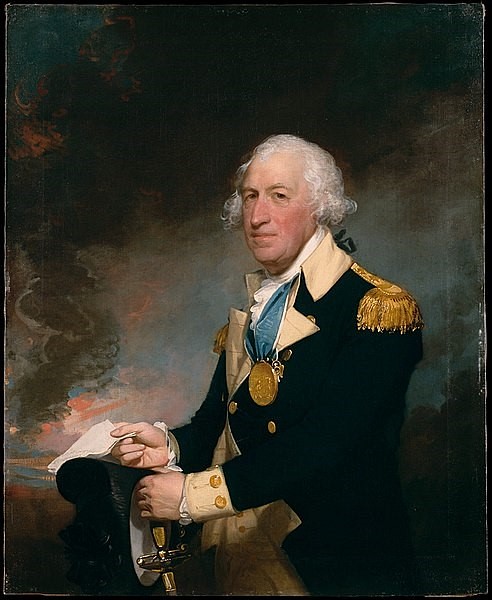

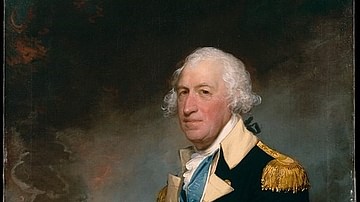

During the same campaign season in which Washington lost Philadelphia, another American general was winning glory for the fledgling United States. General Horatio Gates, commander of the Northern Department of the Continental Army, had won a great victory over a British army at the Battles of Saratoga (19 September and 7 October 1777), in which he compelled the surrender of General John Burgoyne and captured an entire British army. The victory was so spectacular that it would serve as the catalyst for France's entry into the war as a US ally the following year. While it is debatable how much of the credit belongs to Gates himself – Benedict Arnold played a major role, as did Daniel Morgan and several other officers – the general certainly did not hesitate to take full credit in his official report of the battle, which did not mention Arnold's name at all. Gates, perhaps aware of Washington's waning popularity, sent the report directly to Congress, breaching protocol by not sending it to his commander-in-chief first. Almost a full month passed before Gates finally reported the victory to Washington, adding the snide comment that he assumed the general had already heard the news.

Washington interpreted the snub to mean that Gates was gunning for his job. Indeed, several members of Congress secretly welcomed the idea of Gates as the new commander-in-chief; Gates had, so far, been the only American general to force the surrender of an entire British army and was therefore believed to possess the energy and drive that Washington apparently lacked. General Thomas Mifflin of Pennsylvania lamented as much in a letter to Gates:

We have had a noble army melted down by ill-judged marches – marches that disgrace their authors and directors and which have occasioned the severest and most just sarcasm and contempt of our enemies. How much are you to be envied, my dear general? How different your conduct and your fortune…in short, this army will be totally lost unless you come down and collect the virtuous band who wish to fight under your banner…prepare yourself for a jaunt to this place. Congress must send for you. (Fleming, 72)

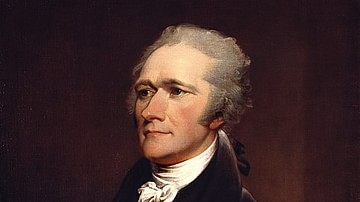

As Washington prepared to enter Valley Forge for the winter, he knew that he must reassert his authority over Gates. In early November 1777, he sent his aide-de-camp, Colonel Alexander Hamilton, to Albany, New York, to request that Gates send most of his army down to join Washington in Pennsylvania. Hamilton, a devout supporter of Washington's, did not try to hide his contempt for Gates when he arrived at the general's headquarters and demanded that he send additional troops to Pennsylvania. Gates, although insulted by Hamilton's headstrong attitude, nevertheless agreed to send at least two brigades south. Hamilton, arriving back at Valley Forge, still could not speak of Gates without disdain, referencing the general's "impudence, his folly and rascality" (Chernow, 102).

Conway's Letter

In December 1777, Washington led his 12,000-man army into winter quarters at Valley Forge, where it would spend one of the most difficult winters of the war. While dealing with the existential troubles that faced the army, such as smallpox and a lack of supplies, Washington simultaneously had to put up with a personal headache, one that went by the name of Thomas Conway. An Irish-born veteran of the French army, Conway had joined the Continental Army the previous spring, enlisting as the most junior of the 24 brigadier generals in the army. It did not take long for Conway to become disappointed with Washington's leadership, particularly regarding Washington's failure to spot a British flanking maneuver at the Battle of Brandywine. At the same time, Conway felt entitled to the rank of major general and continually petitioned Congress for such a rank, even though this would require him jumping over 23 other brigadier generals who had seniority over him.

In late October 1777, Major James Wilkinson, aide-de-camp to General Gates, was out drinking with an officer on the staff of General William Alexander, better known as Lord Stirling. Wilkinson got quite drunk and began to gossip, telling his drinking companion about a particularly nasty letter that Conway had written to Gates in which he derided Washington's leadership. The aide immediately reported this to Lord Stirling, who, in turn, told Washington, noting that Conway's comments were of such "wicked duplicity of conduct" that he felt it his duty to report them (Boatner, 278). Among other criticisms, Conway had apparently referred to Washington as a "weak general" and lamented that he could not serve under General Gates instead. This was blatant insubordination, leading Washington to confront Conway on 9 November. While Conway admitted that he had been critical of the army's conduct in the letter, he denied ever using the phrase 'weak general' to refer to Washington and claimed that he had only meant to praise Gates for his victory at Saratoga.

Conway was, meanwhile, mortified that his private letters had come to light and wrote to Gates, telling him what had happened. Gates was likewise outraged and was determined to find out who had stolen the letter; he decided that it must have been Hamilton, believing that the colonel had copied the letter during his visit to Albany. Gates then wrote an angry letter to Washington, asking him to punish the 'wretch' who 'stealingly copied' letters from his private correspondence; Washington cooly replied that the culprit was not Hamilton, but Wilkinson, Gates' own loud-mouthed aide-de-camp (Boatner, 280).

Board of War

As the fiasco over Conway's letter unfolded, some members of Congress still sought to increase congressional authority over the Continental Army. On 13 December, these members, including Samuel Adams and Dr. Benjamin Rush, decided to accomplish this by revising the Board of War, turning the committee into the top military authority in the United States. Unsurprisingly, they filled the Board with Washington's political enemies; Horatio Gates was named chairman with General Mifflin as his right-hand man. But perhaps the most egregious appointment was Thomas Conway as Inspector General, whose new job required him to supervise Washington and report back to the Board of War. While this was not welcome news to Washington, the commander-in-chief nevertheless did not allow his personal disdain for Conway to interfere with their professional relationship. Washington's subordinates, however, did not take Conway's promotion so lightly; the other brigadier generals felt insulted that Conway, the most junior of their number, had been promoted to Inspector General. Many threatened to resign in protest.

The Board of War immediately began to plan a winter campaign, to solidify its authority over the United States' military. It decided to target Canada and selected the young and dashing French general Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette to lead the expedition, counting on his ability to connect with the French-speaking population of Canada. Excited to have an independent command of his own, Lafayette traveled to Albany, where the preparations for the campaign were being made. His excitement soon turned to disappointment and disgust when he found less than 1,200 soldiers awaiting him, most of them lacking adequate supplies and clothing for the proposed winter campaign. Enraged, Lafayette wrote to Henry Laurens, president of Congress, in which he denounced the Board of War for its poor job of organizing a campaign. The French general also made clear that he would never agree to serve under anyone except Washington and refused to make reports to the Board of War. The plan for a Canadian campaign was scrapped, and Gates' reputation as a brilliant planner was destroyed.

In the spring of 1778, a congressional delegation visited Washington's encampment at Valley Forge. It was headed by Francis Dana, who had been skeptical of Washington's leadership. During his first night at Valley Forge, Dana dined with Washington, who bluntly told him that "Congress does not trust me. I cannot continue thus" (Fleming, 77). Dana, caught off guard by the comment, replied that the majority of Congress still trusted the general. Over the course of the following days, as Dana toured the camp, he became impressed at the way the Continental Army had been retrained during the winter. By the time he returned to York, Dana had become a staunch Washington supporter and lobbied for the general in Congress.

The Cabal Unravels

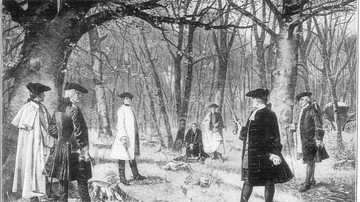

With Washington experiencing a resurgence of popularity in Congress, the so-called 'Conway Cabal' started to unravel. Conway began to face renewed scrutiny over his letter; congressional president Henry Laurens obtained a copy of it, informing Washington that the letter was "ten times worse" than had initially been reported (Boatner, 281). Conway, who was still experiencing the resentment of the army's brigadier generals, now received additional backlash for the letter. Although he continued to deny any ill intent, he submitted his resignation in April 1778, which Congress readily accepted. But Conway did not stop maligning Washington, leading Brigadier General John Cadwalader to challenge him to a duel on 4 July. During the duel, Cadwalader fired a shot that entered Conway's mouth and came out the back of his head; "I have stopped the damned rascal's lying tongue at any rate," an unapologetic Cadwalader exclaimed as he stood over Conway's writhing body (Chernow, 106). Conway survived the injury and returned to France in disgrace.

Gates, meanwhile, tried to save face by offering Washington a written apology. He distanced himself from Conway and from Washington's congressional critics, promising to hereafter be supportive of the commander-in-chief. Having been politically bested, Gates turned his fury on his aide, Wilkinson, whose talkative mouth had started the whole debacle in the first place. Faced with these accusations, Wilkinson challenged his superior to a duel, causing Gates to burst into tears and apologize. The two men reconciled, and the duel was called off. Gates' relationship with Washington, however, was permanently tarnished. As both Conway and Gates were disgraced, any hope for the 'cabal' to succeed faded, as Washington's generals continued to flood Congress with letters supporting their commander-in-chief. On 28 June 1778, Washington attacked a British army at the Battle of Monmouth, dispelling the remaining rumors that he was a timid general. He had won enough of Congress to his side to ensure that there was never another serious attempt to remove him as commander-in-chief.