The Declaration of Independence is the foundational document of the United States of America. Written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, it explains why the Thirteen Colonies decided to separate from Great Britain during the American Revolution (1765-1789). It was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on 4 July 1776, the anniversary of which is celebrated in the US as Independence Day.

The Declaration was not considered a significant document until more than 50 years after its signing, as it was initially seen as a routine formality to accompany Congress' vote for independence. However, it has since become appreciated as one of the most important human rights documents in Western history. Largely influenced by Enlightenment ideals, particularly those of John Locke, the Declaration asserts that "all men are created equal" and are endowed with the "certain unalienable rights" to "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness"; this has become one of the best-known statements in US history and has become a moral standard that the United States, and many other Western democracies, have since strived for. It has been cited in the push for the abolition of slavery and in many civil rights movements, and it continues to be a rallying cry for human rights to this day. Alongside the Articles of Confederation and the US Constitution, the Declaration of Independence was one of the most important documents to come out of the American Revolutionary era. This article includes a brief history of the factors that led the colonies to declare independence from Britain, as well as the complete text of the Declaration itself.

Road to Independence

For much of the early part of their struggle with Great Britain, most American colonists regarded independence as a final resort, if they even considered it at all. The argument between the colonists and the British Parliament, after all, largely boiled down to colonial identity within the British Empire; the colonists believed that, as subjects of the British king and descendants of Englishmen, they were entitled to the same constitutional rights that governed the lives of those still in England. These rights, as expressed in the Magna Carta (1215), the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, and the Bill of Rights of 1689, among other documents, were interpreted by the Americans to include self-taxation, representative government, and trial by jury. Englishmen exercised these rights through Parliament, which, at least theoretically, represented their interests; since the colonists were not represented in Parliament, they attempted to exercise their own 'rights of Englishmen' through colonial legislative assemblies such as Virginia's House of Burgesses.

Parliament, however, saw things differently. It agreed that the colonists were Britons and were subject to the same laws, but it viewed the colonists as no different than the 90% of Englishmen who owned no land and therefore could not vote, but who were nevertheless virtually represented in Parliament. Under this pretext, Parliament decided to directly tax the colonies and passed the Stamp Act in 1765. When the Americans protested that Parliament had no authority to tax them because they were not represented in Parliament, Parliament responded by passing the Declaratory Act (1766), wherein it proclaimed that it had the authority to pass binding legislation for all Britain's colonies "in all Cases whatsoever" (Middlekauff, 118). After doubling down, Parliament taxed the Americans once again with the Townshend Acts (1767-68). When these acts were met with riots in Boston, Parliament sent regiments of soldiers to restore the king's peace. This only led to acts of violence such as the Boston Massacre (5 March 1770) and acts of disobedience such as the Boston Tea Party (16 December 1773).

While the focal point of the argument regarded taxation, the Americans believed that their rights were being violated in other ways as well. As mandated in the so-called Intolerable Acts of 1774, Britain announced that American dissidents would now be tried by Vice-Admiralty courts or shipped to England for trial, thereby depriving them of a jury of peers; British soldiers could be quartered in American-owned buildings; and Massachusetts' representative government was to be suspended as punishment for the Boston Tea Party, with a military governor to be installed. Additionally, there was the question of land; both the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act of 1774 restricted the westward expansion of Americans, who believed they were entitled to settle the West. While the colonies viewed themselves as separate polities within the British Empire and would not view themselves as a single entity for many years to come, they had nevertheless become bound together over the years due to their shared Anglo background and through their military cooperation during the last century of colonial wars with France. Their resistance to Parliament only tied them closer together and, after the passage of the Intolerable Acts, the colonies announced support for Massachusetts and began mobilizing their militias.

When the American Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, all thirteen colonies soon joined the rebellion and sent representatives to the Second Continental Congress, a provisional wartime government. Even at this late stage, independence was an idea espoused by only the most radical revolutionaries like Samuel Adams. Most colonists still believed that their quarrel was with Parliament alone, that King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) secretly supported them and would reconcile with them if given the opportunity; indeed, just before the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775), regiments of American rebels reported for duty by announcing that they were "in his Majesty's service" (Boatner, 539). In August 1775, King George III dispelled such notions when he issued his Proclamation of Rebellion, in which he announced that he considered the colonies to be in a state of rebellion and ordered British officials to endeavor to "withstand and suppress such rebellion". Indeed, George III would remain one of the biggest advocates of subduing the colonies with military force; it was after this moment that Americans began referring to him as a tyrant and hope of reconciliation with Britain diminished.

Writing the Declaration

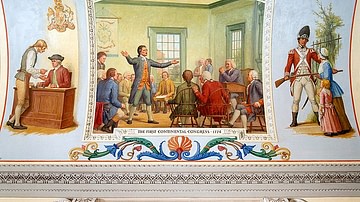

By the spring of 1776, independence was no longer a radical idea; Thomas Paine's widely circulated pamphlet Common Sense had made the prospect more appealing to the general public, while the Continental Congress realized that independence was necessary to procure military support from European nations. In March 1776, the revolutionary convention of North Carolina became the first to vote in favor of independence, followed by seven other colonies over the next two months. On 7 June, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a motion putting the idea of independence before Congress; the motion was so fiercely debated that Congress decided to postpone further discussion of Lee's motion for three weeks. In the meantime, a committee was appointed to draft a Declaration of Independence, in the event that Lee's motion passed. This five-man committee was comprised of Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia.

The Declaration was primarily authored by the 33-year-old Jefferson, who wrote it between 11 June and 28 June 1776 on the second floor of the Philadelphia home he was renting, now known as the Declaration House. Drawing heavily on the Enlightenment ideas of John Locke, Jefferson places the blame for American independence largely at the feet of the king, whom he accuses of having repeatedly violated the social contract between America and Great Britain. The Americans were declaring their independence, Jefferson asserts, only as a last resort to preserve their rights, having been continually denied redress by both the king and Parliament. Jefferson's original draft was revised and edited by the other men on the committee, and the Declaration was finally put before Congress on 1 July. By then, every colony except New York had authorized its congressional delegates to vote for independence, and on 4 July 1776, the Congress adopted the Declaration. It was signed by all 56 members of Congress; those who were not present on the day itself affixed their signatures later.

Text

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.

When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. – That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, – That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive toward these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such a form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and, accordingly, all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. – Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused to Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavored to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws of Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences:

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rules into these Colonies

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, be declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections against us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by the Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. – And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Signers

The following is a list of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence, many of whom are considered the Founding Fathers of the United States. John Hancock, as president of the Continental Congress, was the first to affix his signature. Robert R. Livingston was the only member of the original drafting committee to not also sign the Declaration, as he had been recalled to New York before the signing took place.

Massachusetts: John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Robert Treat Paine, Elbridge Gerry.

New Hampshire: Josiah Bartlett, William Whipple, Matthew Thornton.

Rhode Island: Stephen Hopkins, William Ellery.

Connecticut: Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington, William Williams, Oliver Wolcott.

New York: William Floyd, Philip Livingston, Francis Lewis, Lewis Morris.

New Jersey: Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, Abraham Clark.

Pennsylvania: Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson, George Ross.

Delaware: George Read, Caesar Rodney, Thomas McKean.

Maryland: Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Virginia: George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, Carter Braxton.

North Carolina: William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, John Penn.

South Carolina: Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward Jr., Thomas Lynch Jr., Arthur Middleton.

Georgia: Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, George Walton.