The US presidential election of 1789 was the first presidential election to take place after the ratification of the United States Constitution. Held on 4 February 1789, it resulted in the unanimous election of George Washington (l. 1732-1799) as the first president of the United States, with John Adams (l. 1735-1826) elected as the first vice president.

This election was very different from modern-day presidential elections in the United States. For one thing, candidates did not campaign for office, as outward displays of political ambition were viewed with suspicion by the public; instead, aspiring politicians discreetly made their interests known while their allies publicly lobbied for them. Additionally, as there were not yet any formal political parties, presidential and vice presidential candidates did not run on a shared ticket. Instead, the candidate who received the most votes from the Electoral College became president, while the runner-up became vice president. Finally, the president was chosen by electors – who were themselves selected by each state through various methods – who were each allowed to cast two votes. Washington, after his unanimous election, travelled to the temporary US capital of New York City, where he was inaugurated on 30 April 1789.

Background

In March 1781, as the American Revolutionary War neared its end, the Articles of Confederation went into effect as the first framework of governance for the fledgling United States. The Articles, which bound the 13 states together in a league of perpetual union, deliberately kept the new central government weak to protect the sovereignty of the individual states. Congress' lack of authority would soon lead to problems, however; the central government's inability to raise its own taxes meant that the national treasury was constantly depleted, while its lackluster response to Shays' Rebellion (1786-87) showed that it was ill-equipped to handle domestic crises. By the mid-1780s, many Americans viewed the Articles of Confederation as ineffectual and demanded they be revised, if not replaced. George Washington certainly spoke for many of his contemporaries when he called the Confederation Congress a "half-starved, limping Government that appears to be always moving upon crutches and tottering at every step" (mountvernon.org).

On 25 May 1787, the Constitutional Convention met at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with Washington presiding. While the initial goal of the convention had been merely to revise the Articles of Confederation, it was soon decided that an entirely new framework of governance was needed, and the delegates got to work debating and drafting what would become the United States Constitution. As suggested in the Virginia Plan (drafted by Virginian delegates James Madison and Edmund Randolph), it was ultimately decided that the new federal government should consist of three distinct branches: executive, legislative, and judiciary, each expected to exert checks and balances on the others. Debate over the exact powers and functions of these branches consumed much of the convention, particularly regarding the executive branch; under the Articles, the US had no executive officer, as the 'president of Congress' had served more of an administrative role.

On 1 June, it was decided that the nation's chief executive would be a single person rather than a group of persons and that this officeholder would be called the ‘president'. Believing that the masses were too easily manipulated, the delegates decided against electing the president directly through a popular vote and instead set up an Electoral College, wherein voters in each state would choose electors who would, in turn, elect the president. After toying with the idea that the president should serve a single, seven-year term, the delegates instead went with the notion that multiple terms could be served. While the idea of the presidential office seemed foreboding to many convention delegates, who still feared the tyranny of kings, most were lulled into compliance by the idea that Washington would become the first president. Time and again, Washington had demonstrated his patriotism during the American Revolution and had voluntarily resigned his position as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. The idea that he would be the first one to define the office of president did much to ease fears that the office would become an elective monarch.

Candidates

Once the US Constitution had been ratified by the necessary nine states in June 1788, the nation could look forward to its first presidential election. As had been the case at the Constitutional Convention, most Americans assumed that Washington would win the presidency. The general himself voiced little interest in the office, implying that he would rather enjoy his retirement at his home of Mount Vernon. While this may have been true in Washington's case, it was customary at the time for politicians to feign disinterest in political office and act like accepting such a position was a personal sacrifice made for the good of the country; anyone who openly sought or campaigned for a political office was viewed with suspicion. Washington, therefore, did not campaign for the presidency or express much interest in the office but was nevertheless the only candidate who was seriously considered for the job.

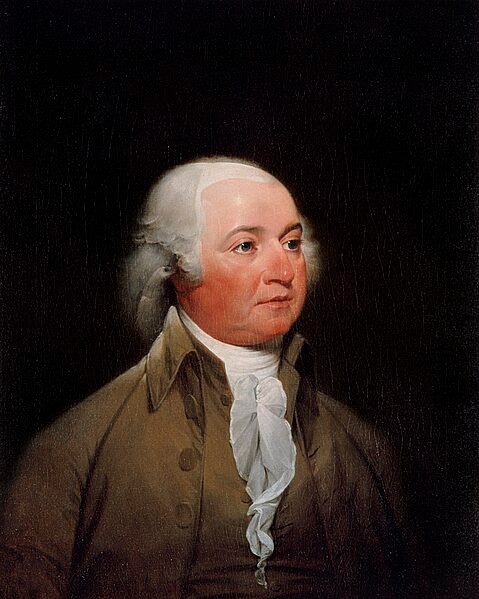

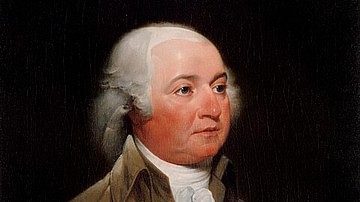

With Washington's election a foregone conclusion, the focus of the first national election was on who would fill the position of vice president. At this point, the vice presidency was an ill-defined office, whose only role explicitly stated in the Constitution was to preside over the Senate and cast a tie-breaking vote there if necessary. Still, it was recognized as a prestigious position, second only to the president. Since Washington was from Virginia, a Southern state, it was deemed appropriate that the first vice president be from the North; several candidates were considered including John Jay of New York, Samuel Huntingdon of Connecticut, as well as Benjamin Lincoln and John Hancock of Massachusetts. However, the man considered most likely for the job was John Adams of Braintree, Massachusetts, who had played a pivotal role in the American Revolution, spearheading the push for independence and securing much-needed foreign aid. Like Washington, Adams expressed no public interest in the vice presidency, instead spending his time working on his farm. But unlike Washington, Adams did want the job and privately told his wife Abigail that any position less than vice president in the new government would be "beneath him" (Chernow, 271).

The Election

The states began to select their presidential electors on 15 December 1788, a process that would take a little over three weeks. The methods for choosing electors varied from state to state. In some states, electors were chosen through popular vote, while in others, they were appointed by the state legislature. By the deadline of 7 January 1789, electors had been selected from ten states: Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia. Of the other three states, the New York legislature had been unable to agree on a method for choosing electors before the deadline and therefore failed to send any at all, while North Carolina and Rhode Island had not yet ratified the Constitution and could not participate in the election.

The Electoral College convened on 4 February 1789. There were 69 electors, each of whom was allowed to cast two votes; the candidate who received the most votes would become president, while the runner-up would become vice president. In the event of a tie – which was unlikely to happen in this particular race – the decision would be given to the House of Representatives. As expected, each elector cast his first vote for George Washington, who was unanimously elected with all 69 electoral votes. The race for the vice presidency was hardly more contentious, as John Adams easily won with 34 votes; the vice presidential candidate with the second-most number of votes, John Jay, received only nine.

Despite his clear victory, Adams felt disappointed that he had not won more than half of the available electoral votes; especially when compared to the unanimity of Washington's election, Adams felt humiliated and personally slighted by his own weak show of support. Unbeknownst to him, the reason he did not get more votes was because of the machinations of Alexander Hamilton. Worried that Adams might accidentally get more votes than Washington and become president, Hamilton had approached several electors during the winter and convinced them to withhold their votes from Adams. This proved an unnecessary precaution, since every elector voted for Washington anyway, and only served to injure the vanity of Adams, who railed against such a "dark and dirty intrigue" (Chernow, 273).

Inauguration of Washington

As the Electoral College cast its votes, Washington sat at home at Mount Vernon, awaiting the results. Although the decision had been made in February, Congress had been unable to count the votes until it reached a quorum on 6 April. Once the votes were tallied, Congress dispatched Charles Thomson, Secretary of Congress, to Mount Vernon to inform Washington of his election. Washington accepted and, on 16 April 1789, began an eight-day procession to New York City, the temporary capital of the United States. It was a journey filled with fanfare. Cannons sounded and church bells pealed at each town he passed through, while large crowds gathered to catch a glimpse of the president-elect. While passing through Trenton, New Jersey, the site of one of his most famous battles, Washington was greeted by a thirteen-pillared triumphal arch as well as thirteen young women dressed in white who sang as they spread flower petals before him. At Elizabethtown (modern Elizabeth, NJ), he boarded a luxurious barge towed by thirteen pilots that carried him across the Hudson River to New York City.

By the time Washington arrived in New York, Adams had already been inaugurated as vice president (on 21 April) and had been presiding over sessions of the US Senate. On 30 April 1789, the day of Washington's own inauguration, a massive crowd gathered outside Federal Hall. From the second-floor balcony, Robert R. Livingston, Chancellor of New York, administered the presidential oath. At the conclusion of the oath, Washington kissed the Bible on which he had sworn, as Livingston turned to the crowd to proclaim: "Long live George Washington, President of the United States!" (Wood, 65). The resultant cheer was so loud that it apparently drowned out the ringing of church bells. Washington then went to the Senate chamber where he delivered a brief, 1,400-word inaugural address; he was so overcome with emotion that he had difficulty reading the words.

With the exceptions of Adams' perceived insult and the fanfare of Washington's procession to New York City, the presidential election of 1789 proved a rather straightforward and drama-free affair. Aside from Washington's re-election in 1792 – also unanimous – it was the only non-contentious presidential election and the only one not influenced by organized political parties. The US presidential election of 1796, which would pit John Adams and the Federalist Party against Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republican Party, would largely influence the way in which national elections and American politics were treated thereafter.