On the eve of the American Revolution (1765-1789), the Thirteen Colonies had a population of roughly 2.1 million people. Around 500,000 of these were African Americans, of whom approximately 450,000 were enslaved. Comprising such a large percentage of the population, African Americans naturally played a vital role in the Revolution, on both the Patriot and Loyalist sides.

Black Patriots

On 5 March 1770, a mob of around 300 American Patriots accosted nine British soldiers on King Street in Boston, Massachusetts. Outraged by the British occupation of their city, as well as the recent murder of an 11-year-old boy, the crowd was filled with Bostonians from all walks of life; among them was Crispus Attucks, a mixed-race sailor commonly thought to have been of African and Native American descent. When the British soldiers fired into the crowd, Attucks was struck twice in the chest and was believed to have been the first to die in what became known as the Boston Massacre. He is regarded, therefore, as the first casualty of the American Revolution and has often been celebrated as a martyr for American liberty.

Five years later, in the early morning hours of 19 April 1775, a column of British soldiers was on its way to seize the colonial munitions stored at Concord, Massachusetts, when it was confronted by 77 Patriot militiamen on Lexington Green. Standing in this cluster of militia was Prince Estabrook, one of the few enslaved men to reside in Lexington, who had picked up a musket and joined his white neighbors in defending his home. In the ensuing Battles of Lexington and Concord, Estabrook was wounded in the shoulder but recovered in time to join the Continental Army two months later. He was selected to guard the army headquarters at Cambridge during the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775) and was freed from slavery at the end of the war.

Attucks and Estabrook were just two of the tens of thousands of Black Americans who supported the American Revolution. There was no single motivation for their doing so. Some, of course, were inspired by the rhetoric of white revolutionary leaders, who used words like 'slavery' to describe the condition of the Thirteen Colonies under Parliamentary rule and promised to forge a new society built on liberty and equality. These words obviously appealed to the enslaved population, many of whom were optimistic that, even if slavery was not entirely abolished, they might receive better opportunities in this new nation. Others enlisted in the Continental Army to secure their individual freedoms, as the Second Continental Congress had proclaimed that any enslaved man who fought the British would be granted his freedom at the end of his service. African Americans also enlisted to escape the day-to-day horrors of slavery, to collect the bounties and soldiers' pay offered by recruiters, or simply because they were drawn to the adventure of a soldier's life. Additionally, several Black Americans were forced to enlist by their Patriot masters, who preferred to send their slaves to fight instead of going themselves.

Of course, not all Black Patriots served in the Continental Army or Patriot militias. Some, like James Armistead Lafayette, were spies; posing as a runaway slave, Lafayette was able to infiltrate the British camp of Lord Charles Cornwallis and procure vital information that helped lead to the Patriot victory at the Siege of Yorktown. The French general Marquis de Lafayette was impressed with his service and helped procure his freedom after the war, leading James Lafayette to adopt the marquis' name.

Other Black Patriots showed their support for the movement with their words. Phillis Wheatley was an enslaved young woman who had been brought to Boston from Senegal, where she had been seized. She was purchased by the Wheatley family, who quickly recognized her literary talents and encouraged her to write poetry. By the early 1770s, Phillis Wheatley was already a celebrated poet. She began to write extensively on the virtues of the American Revolution, praising Patriot leaders like George Washington. Despite his status as a slaveholder, Washington was moved by Wheatley's work and invited her to meet him, stating that he would be honored "to see a person so favored by the muses" (Philbrick, 538).

African Americans in the Continental Army

Many Black Americans, like Prince Estabrook, had joined Patriot militias even before the outbreak of war. Some even underwent the extra training that it took to become a 'minuteman', ready to fight at a minute's notice. So, when these various militia groups coalesced into the Continental Army during the Siege of Boston (20 April 1775 to 17 March 1776), many Black men were already fighting alongside the Patriots. However, many white revolutionary leaders were uncomfortable giving arms and training to enslaved men; especially in the American South, where the number of slaves outnumbered the free population in certain areas, white colonists lived in constant fear of slave revolts and dreaded the consequences of arming the enslaved population. For this reason, in May 1775 the Massachusetts Provincial Congress resolved that "no slaves be admitted into this army upon any consideration whatever" (American Battlefield Trust).

When George Washington took command of the Continental Army two months later, he took this a step further and barred any Black man from serving in the army, even if they were free. This order was met with resistance from several white officers, who argued that their Black soldiers were no less loyal, brave, or willing to fight than their white soldiers. Washington eventually changed his mind and rescinded the order, allowing officers to recruit Black soldiers at their own discretion. Some state legislatures, who were each given recruitment quotas by Congress, also began recruiting Black Americans to meet these quotas more easily.

Ultimately, at least 5,000 Black soldiers and sailors served the Patriot cause across the duration of the war, although some estimates place this number even higher. By 1777, most Continental regiments had at least some Black soldiers, making the Continental Army the most racially integrated army in US history prior to the 1940s. In July 1781, just before the Siege of Yorktown, Baron Ludwig von Closen reported that around a quarter of Washington's troops were Black (an estimate, if accurate, which would amount to 1,054 Black soldiers), describing these troops as "merry, confident, and sturdy" (American Battlefield Trust). The accuracy of Closen's report is debated, but it is true that a larger number of Black soldiers were serving in the Continental Army in the latter years of the war. Black soldiers were not treated equally to their white comrades – they could not advance beyond the rank of private soldier, for instance – but they did receive equal pay and were given the same quality clothes, food, and equipment as the white soldiers.

Black Loyalists

Just as many Black Patriots hoped that the United States would give them their freedoms, many other Black Americans sought their salvation with the British. At the time, abolitionist sentiment was rising in Great Britain. In a 1772 court case, Somerset v. Stewart, the English Court of King's Bench ruled that the institution of slavery was not supported by the common laws of England and Wales. The case was followed very closely by the American colonists, and, although it did not speak to the legality of slavery in other parts of the British Empire, it was seen as a massive win by abolitionists. Some enslaved African Americans began stowing away on ships bound for the British Isles, hoping to gain their freedom by setting foot on English soil. American slaveholders, on the other hand, began to fear that the British were planning to deprive them of their slaves, driving yet another wedge between white colonists and Great Britain.

Shortly after the outbreak of the war, British officials looked to capitalize on the Americans' fear of slave revolts. In November 1775, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation that promised freedom to all enslaved persons belonging to Patriot masters who deserted their owners and joined the British army. Within days of the Dunmore Proclamation, over 800 slaves had escaped their masters and joined up with Dunmore, who organized many of them into an all-Black military unit known as Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment (more on this below). Naturally, the Dunmore Proclamation alarmed the Patriots, many of whom threatened their slaves with death should they run off to join the British. The proclamation also hastened the Patriots' decision to offer slaves freedom in exchange for service in the Continental Army, to prevent more of them from flocking to the British.

In 1779, Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British army in North America, issued the Philipsburg Proclamation. An expansion of the earlier Dunmore Proclamation, the Philipsburg Proclamation stipulated that all enslaved people who escaped from Patriot owners would be freed if they could reach British lines, regardless of age or gender. Thanks to these two proclamations, an estimated 20,000 African Americans sought refuge with the British during the course of the war; 17 of George Washington's slaves ended up escaping Mount Vernon to take refuge on a British warship. Many Black Loyalists and runaway slaves were familiar with the American countryside and served as guides for the British army during various campaigns.

Of course, many of these Black Loyalists ended up fighting for the British. At the Siege of Savannah (16 September to 20 October 1779), the British recruited Black Loyalists to bolster their defenses against a Franco-American assault. Additionally, several all-Black units of Loyalist militia were created. The most famous of these was the Black Brigade, a unit of 24 Black Loyalists that operated in Monmouth County, New Jersey, under the command of Colonel Tye. Himself a runaway slave, Colonel Tye became one of the most feared Loyalist partisans of the war, leading several successful raids on the homes of prominent New Jersey Patriots in the summer of 1780 before dying from an infection caused by a wound.

All-Black Military Units

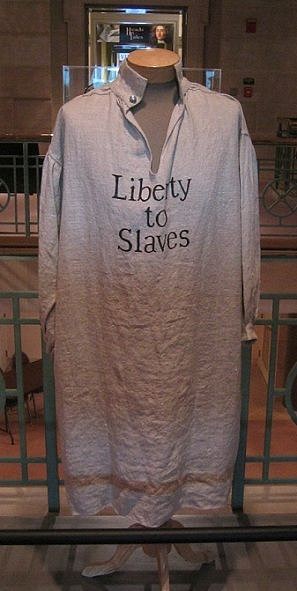

While most Black soldiers on both sides served in integrated units, there were several instances of all-Black or primarily Black military units. The most prominent of these on the Loyalist side was Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment. Commanded by white officers, the Ethiopian Regiment was comprised of enslaved men who had escaped from their Patriot masters. Each soldier was given a gray uniform, imprinted with the words 'Liberty to Slaves'. In late 1775 and early 1776, the Ethiopian Regiment saw action in several skirmishes in Virginia. However, its ranks were decimated by a smallpox outbreak, and the unit was disbanded in the summer of 1776. Many veterans of the Ethiopian Regiment continued to fight for the British, including Colonel Tye, whose Loyalist militia, the Black Brigade, was another all-Black unit. The Black Brigade continued to operate after Tye's death, with its members eventually settling in Canada.

On the Patriot side, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment was a unit comprised mainly of Black and Native American troops. Colonel Christopher Greene, the regiment's commander, was commissioned to recruit enslaved men in exchange for freedom, resulting in 140 Black or Indigenous soldiers fighting in the regiment, out of a total of 225 troops. The regiment performed exceedingly well at the Battle of Rhode Island (29 August 1778), in which they held the right flank against a series of Hessian assaults, earning praise from Patriot General John Sullivan and Marquis de Lafayette. The regiment continued to serve until the Siege of Yorktown, during which one French officer described the Black soldiers as "the most neatly dressed, the best under arms, and the most precise in all their maneuvers" (Kaplan, 56). The regiment was disbanded along with the rest of the Continental Army in 1783.

After the War

After the Patriot victory at the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781, it was clear that Black Loyalists had bet on the wrong side. As part of the ceasefire negotiations, Congress instructed General Washington to negotiate a return of all private property that the British army had confiscated from the Patriots during the war – this included the thousands of runaway slaves that were sheltering behind British lines. Having briefly tasted freedom, it seemed as though the Black Loyalists would soon be returned to a life of bondage. Luckily, Sir Guy Carleton, the new British commander-in-chief, was determined to honor his commitment to Black Loyalists. Rather than give in to Washington's demands, Carleton offered a compromise: if the Patriots allowed the Black Loyalists to evacuate with the British army, then the British government would financially compensate all Patriot slaveholders for each slave they lost.

Unwilling to jeopardize peace negotiations over this issue, Washington accepted Carleton's proposal. Over 3,000 Black Loyalists accompanied the British army when it evacuated New York City in November 1783. Many of them initially settled in Nova Scotia, taking up residence in the community of Birchtown. However, many Black Loyalists found life at Birchtown to be miserable, faced with an uncomfortable climate, insufficient supplies, and lack of support from the local administration. Additionally, the free Blacks of Birchtown faced constant discrimination from their Canadian neighbors and became the target of violence during the 1784 Shelbourne Riots. Consequently, 1,200 Black Loyalists opted to leave Nova Scotia in 1792 to settle in the new British colony of Freetown, Sierra Leone, in West Africa. Many other Black Loyalists also evacuated the United States in the wake of the Revolution, settling in the West Indies or Florida. The British did not free every slave who evacuated with them, however, as there were still many Loyalist slaveholders who left with the British army and were allowed to keep their slaves. Slavery in Britain itself would ultimately be abolished in 1807.

As for the Black Patriots, they were released from military service when the Continental Army was disbanded in December 1783. Most of those who had been enslaved before the war were freed, as promised by Congress. But others were not, as crafty slaveholders found ways to back out of their promises and keep their slaves in bondage. On several occasions, Black veterans were even kidnapped and sold back into slavery. But even for the majority of Black soldiers who were emancipated, life in the postwar United States was not easy. Congress was struggling to pay Continental soldiers the back pay and pensions it owed them; while this was a difficult situation for all soldiers, it was even worse for Black veterans, who had much fewer opportunities for employment than their white counterparts. Many were only able to find low-paying work on farms, finding themselves in a situation that was only marginally better than enslavement. Black soldiers could not even make a living in the army, as Congress officially prohibited non-whites from serving in the US military in 1792.

Still, many white officers did not abandon the Black soldiers formerly under their command. Men like Lt. Colonel Jeremiah Olney of the 1st Rhode Island frequently went to court to help Black veterans sue for the back pay and pensions owed to them. Thanks in part to Olney's advocation, the Rhode Island Assembly would address the issue in February 1785 in an act that required all communities to take care of Black and Indigenous veterans who could not support themselves. In the first few decades of the United States' existence, northern states gradually worked to abolish slavery, setting the divide between 'free states' and 'slave states' that would ultimately lead to the American Civil War (1861-1865).