The Declaration of Pillnitz was a joint statement issued on 27 August 1791 by Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1790-1792) and King Frederick William II of Prussia (r. 1786-1797). The declaration appealed to all European powers to unite against the French Revolution (1789-99) and restore King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792), reduced to a constitutional monarch, to his full powers.

Despite taking such a seemingly belligerent position against Revolutionary France, the declaration was much more of a political formality than a serious threat. The monarchs of Europe were apprehensive of the Revolution and were worried about the possibility of it spreading beyond France's borders. Leopold II was also concerned about the safety of his sister, French Queen Marie Antoinette (1755-1793). Yet, neither Leopold nor Frederick William intended to go to war with France and worded the declaration in such a way that they would only be obliged to commit troops if every other European power did as well, something that was very unlikely to occur. The declaration was only meant to appease royalist French émigrés, intimidate the French revolutionaries into pursuing less radical policies, and satisfy Leopold II's family honor.

The declaration, however, would backfire when it was taken at face value by the French, who had long been fearing foreign invasion. Opposite of its intended effect, the Declaration of Pillnitz would raise tensions in Europe, resulting in France's declaration of war against Austria on 20 April 1792, sparking the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802).

A Diminished Crown

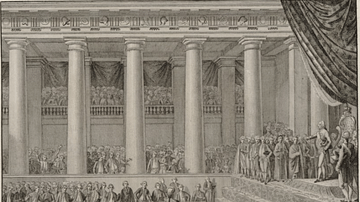

The French Revolution had begun on 5 May 1789, when King Louis XVI and his ministers were compelled to convene the Estates-General of 1789 to solve France's dire financial difficulties. Far from stabilizing the kingdom, the Estates-General instead resulted in the rise of the Third Estate (commoners), who instituted a National Assembly and insisted on their right to craft a new constitution. Louis XVI's attempts to regain control over the Assembly were foiled when the commoners of Paris rose up and stormed the Bastille. Afterwards, the heir to Bourbon absolutism was forced to abide the diminishment of his monarchy and the destruction of France's Ancien Régime; the Assembly's decision on the night of 4 August 1789 to abolish feudalism (August Decrees) was followed by the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which championed Enlightenment ideals such as the natural rights of man and Rousseau's theory of the general will.

Following the Storming of the Bastille, Louis XVI had twice resisted the rising tide of Revolution, both times proving detrimental to his position. The first occasion was when he refused to consent to the August Decrees and the Declaration of the Rights of Man; this resulted in the Women's March on Versailles on 5 October 1789, when 7,000 of Paris' market women descended on the Palace of Versailles and compelled the king and his family to accompany them back to Paris. There, he was installed in the Tuileries Palace as a virtual prisoner. The second time the king had defied the Revolution was his most egregious offense. On the night of 20-21 June 1791, he and his family had slipped out of Paris under the cover of night, riding hard in their carriage for the border with the Austrian Netherlands. They were soon caught by diligent French patriots in the town of Varennes-en-Argonne and escorted back to Paris. The king's flight to Varennes was a traumatic moment for many French citizens, who felt betrayed by their king. The incident resulted in calls for his abdication and even for the establishment of a French Republic.

Naturally, these developments were alarming to French royalists and aristocrats, who began to leave France in droves following the fall of the Bastille. Louis XVI's youngest brother, Charles-Philippe, comte d'Artois (future King Charles X of France) led the first wave of émigrés, departing Versailles on 16 July 1789, two nights after the Bastille. With him went the scions of many of France's most illustrious and noble families, including the Prince de Condé, the Polignacs, and the Rohans. Artois and his followers had not expected to be away from Versailles for long; but in the weeks that followed, popular uprisings throughout France resulted in the burning of noble châteaux and culminated in the destruction of the feudal regime on 4 August. They were soon joined in their flight by others who had become increasingly apprehensive of the Revolution's direction. Especially after the March on Versailles, thousands of aristocrats, clerics, and public officials left France, many establishing themselves just beyond the border in cities like Brussels, Trier, and Mainz. Artois himself would settle in the court of Turin, under the protection of his father-in-law King Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia (r. 1773-1796).

The National Assembly did nothing to stop these waves of émigrés from leaving France (excluding the king and queen, of course). In 1789 and 1790, the French border was open to anyone, since to do otherwise would infringe on individual liberties. Yet after Varennes, the Assembly's open border policy became problematic; in 1791, at the call of Artois and the Prince de Condé, who had set himself up in Worms, over 6,000 French military officers would desert their posts and travel abroad before the end of the year. This was an alarming loss of experienced soldiers, amounting to around three-quarters of all officers in the royal army. Many of these military men would gather around Artois and Condé, looking to help instigate counter-revolution, by force of arms if necessary.

Émigré Influence

In November 1790, Artois was joined in Turin by an unlikely ally. Charles-Alexandre de Calonne had once served as Louis XVI's hapless finance minister, who had gone into exile in London after he failed to pass crucial reforms during the Assembly of Notables of 1787. Calonne had since married a rich heiress and was prepared to use her wealth to help Artois in his counter-revolutionary endeavors. Together, the two planned a counter-revolution, which pursued three goals:

- to organize Louis XVI’s escape

- to instigate insurrections within France itself

- to persuade European powers to intervene

Of these goals, all hopes of achieving the first ended with the king's capture at Varennes, an escape attempt Artois had not even been aware of. The second was marginally successful, as the pair were able to provoke insurrections in Languedoc and the Rhone Valley, although these did not make much of a difference. Thus, the hopes of the hotheaded prince and disgraced finance minister lay with the rulers of Europe, who were undoubtedly watching the events in France unfold with mounting unease. Unable to foresee much help from King Victor Amadeus, the pair left Turin, looking to set up court in a location more conducive to their schemes.

They settled on Koblenz, a city on the Rhine that was already a French émigré hotspot. By mid-June, Artois was firmly established there, having formed a counter-revolutionary court that soon swelled with some of France's best military officers. Before long, Artois and Calonne possessed an émigré army of roughly 20,000 men; an impressive force, it was still not enough to beat the armies of France on its own. Soon joined by his brother, Louis-Stanislas, comte de Provence (future Louis XVIII of France), Artois and his allies looked to a man with the means and possible motivation to help them: Louis XVI's brother-in-law, the Habsburg emperor Leopold II.

Leopold’s Dilemma

By this point, Emperor Leopold II had occupied the Habsburg throne for a little over a year, having been thrust into the position by the untimely death of his elder brother, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1765-1790). The empire Leopold inherited was an unstable one in the grips of its own crisis; entire provinces were in unrest thanks to Joseph II's policies of anti-aristocratic, secular, modernizing reform that were part of his attempt to create an Enlightened state. It showed tremendous pragmatism on Leopold's part to be able to restore order to the Habsburg domains in the short amount of time he was able to, partly by rescinding some of his brother's most unpopular reforms and partly by military intervention.

If this was not enough to deal with, Leopold II had also inherited a war with the Ottoman Empire, which was winding down, though it had not gone well for the Austrians. At the same time, he was acutely aware of the events taking place in Poland, which Prussia and Russia were soon to partition for a second time. With all this going on, the French Revolution would have been little more than a sideshow, something that deserved attention but was not a top priority. In terms of foreign policy, Leopold, along with many other European leaders, saw some positives in the early Revolution, as it appeared to be weakening France as a rival.

Still, he was concerned for the safety of his sister, Marie Antoinette. He had not seen her in over 25 years and had never viewed her with the same fondness that Joseph II had. But she was still his sister and a Habsburg. Her near-death experience at the hands of the rabble on 6 October 1789 had proved to Leopold that her life could truly be in danger. Yet, he had refrained from military action in France thus far, not only because it was not in Austria's best interest but also because such an action could put his sister and her children in further peril. Leopold II had tried to come to Marie Antoinette's aid through other means; having been privy to the attempted escape on 21 June, he had ordered four regiments to the border with France, ready to receive the French king and queen when they crossed over. Having mistakenly believed that the attempt had succeeded, Leopold even wrote Marie Antoinette, promising her that "Everything I have is yours, money, troops, everything" (Schama, 590).

His concern deepened after Varennes when public opinion in France turned sharply against the royal family, as well as against Austria. Since the Great Fear of 1789, French citizens had long feared an Austrian or British invasion, and whispers now abounded that the Austrians planned to march into France and rescue the king and queen by force. Talks of republicanism, unthinkable only a few months before, became more prevalent, and certain revolutionary figures began to speak openly of war. Amidst this backdrop, Leopold could no longer remain silent. On 10 July, he sent the Padua Circular to his fellow monarchs, which asked them to join him in condemning the actions of France and demanding the freedom of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. However, the Padua Circular was met with little enthusiasm from Europe's rulers, except for King Frederick William II of Prussia. Despite the traditional rivalry between the Hohenzollerns of Prussia and the Habsburgs of Austria, the two monarchs agreed to meet on 25 July in the spa of Pillnitz, Saxony.

The Declaration of Pillnitz

Leopold II and Frederick William II were joined in Pillnitz by Artois and Calonne, who arrived unexpected and completely uninvited. The émigrés wished to see these European powers finally make common cause with them in declaring war on France's insolent revolution. Yet, if Artois and Calonne expected decisive action to be taken at Pillnitz, they were to be disappointed. Leopold agreed that something had to be done, but his goal was more to preserve Habsburg family honor than anything else. He was reluctant to go to war and even more reluctant to join forces with the distrusted Prussians. Rather than an ultimatum, the declaration was closer to a vague warning, albeit one neither monarch hoped to have to back up. Only five sentences long, the declaration read:

His Majesty the Emperor [of Austria] and his Majesty the King of Prussia ... jointly declare that they regard the present situation of his Majesty the king of France as a matter of common interest to all the sovereigns of Europe. They trust that this interest will not fail to be recognized by the powers whose aid is solicited; and that in consequence they will not refuse to employ ... the most efficient means, in proportion to their resources, to place the king of France in a position to establish, with the most absolute freedom, the foundations of a monarchical form of government, which shall at once be in harmony with the rights of sovereigns and promote the welfare of the French nation.

In that case, their said Majesties the emperor and the king of Prussia are resolved to act promptly and in common accord with the forces necessary to obtain the desired common end. In the meantime, they will give such orders to their troops as are necessary in order that these may be ready to be called into active service.

Signed,

Leopold, Emperor of Austria

Frederick William, King of Prussia

August 27th 1791(Above text cited from alphahistory.com)

The Declaration of Pillnitz was deliberately worded to give the impression of firmness while simultaneously not committing Austria or Prussia to any specific policies or courses of action. The declaration merely urged the other European powers to support the French monarchy but did not promise military action unless every other European power committed to such a plan. Leopold and Frederick William both knew that this would be extremely unlikely, as British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806) had already made clear that it was against Britain's interests to become embroiled in a conflict on the continent.

Leopold was satisfied with the declaration, believing it would achieve his purposes. He knew that in France the Feuillants, a constitutional monarchist faction, dominated the National Assembly and were working to both restore some power to Louis XVI in the forthcoming constitution and to bring the Revolution to a quick and satisfactory end. By threatening military intervention, Leopold expected others in the Assembly would fall in line with the Feuillants' goal, and that fear of the Austrian army would prevent any more extremist revolutionary policies. Further, Leopold hoped the declaration would placate the pesky French émigrés like Artois and stop them from stirring up trouble. Most importantly for him, however, by issuing the decree, his Habsburg family honor was satisfied. As concerned as he was with his sister's personal safety, the fact remained that Leopold had his own empire to rule, with its own agenda and foreign policy. This was underscored by the fact that most of the Pillnitz Conference dealt not with the Revolution, but with the question of Polish partition and with the war against the Ottomans. Although currently on the backburner, the French Revolution would quickly become a very pressing issue.

French Reaction

The Declaration of Pillnitz was written with the stuffy diplomatic language of monarchs. Its true intentions were hidden behind a façade of saber-rattling, meant to be discerned by reading in between the lines. This was the typical diplomatic language of the day. The French revolutionaries, by contrast, sneered at this archaic form of communication, believing that language between citizens should be sincere, transparent, and direct.

It was all too easy, therefore, for members of the Assembly to present the declaration as an affront to peace, as proof that the foreign powers of Europe were plotting with the émigrés against the Revolution. Hérault de Séchelles, a Jacobin and future member of the Committee of Public Safety, described the declaration as revealing "a huge conspiracy against the liberty not only of France, but of the whole human race" (Schama, 591). Despite evidence that the Austrians were actively disbanding regiments rather than raising them, the declaration whipped up the rumors that had been causing panic since the Revolution began; suddenly, there were whispers that the Austrians were amassing along the border, that colossal British warships were sailing for Brittany. It was the Great Fear all over again.

Naturally, the émigrés were blamed. All those who defied the interests of the patrie (fatherland), were now designated under the category of 'foreigner', regardless of their place of birth. In the Assembly, action was finally taken against the émigrés. On 31 October, it declared all émigrés who had not returned to France by 1 January 1792 to be guilty of conspiracy and sentenced to death. On 9 November, the Assembly gave the Comte de Provence two months to return to the country before it would revoke his place in the line of succession. Finally, on 29 November, the Assembly announced that it would confiscate all émigré property, including land owned by family members who had remained in France. Louis XVI used his royal veto against these draconian laws and even went to the Assembly in person in December to denounce any kind of military intervention by foreign powers. Yet the very fact that these policies had been passed at all showed the direction France was heading.

In September 1791, Revolutionary France showed its defiance to the rest of Europe by annexing Avignon and the Comtat-Venaisson. In response, Austria and Prussia formed a defensive alliance in February 1792. France inched closer to war, now under the influence of Jacques-Pierre Brissot and his Girondist supporters, who believed war to be the best method of unmasking the Revolution's true enemies. Eventually, France issued an ultimatum that Austria renounce its hostile alliance with Prussia and that it withdraw all troops from the border. Austria refused. On 20 April 1792, France declared war on "the king of Hungary and Bohemia", namely Leopold's son and successor, Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor. Prussia entered the war as Austria's ally shortly thereafter, thus beginning the War of the First Coalition (1792-97), the first of the French Revolutionary Wars.