The War of the First Coalition (1792-1797) was a continent-spanning conflict in which a coalition of European powers, including Austria, Prussia, Great Britain, the Dutch Republic, Spain, and several others, sought to contain and defeat Revolutionary France. The war was sparked by the ideals of the French Revolution (1789-1799), which threatened the established monarchies of Europe.

The French revolutionaries, who had long feared military intervention by neighboring monarchies, declared war on Austria on 20 April 1792 to preserve and expand the Revolution. After winning the Battle of Valmy, the French declared themselves a republic, executed their king, and pursued expansionist war goals such as the conquest of Belgium and the Rhineland; these factors drew more nations into the anti-French coalition. By 1793, the Republic was in dire straits, having to fend off enemy armies on all fronts. Through draconian measures such as the Reign of Terror, the Republic was able to crush internal dissent and swell its armies with conscripts.

The French counterattacks, utilizing overwhelming numerical superiority and revolutionary zeal, succeeded in pushing the Allied armies back. The European powers gradually lost heart and began dropping out of the Coalition until the Treaty of Campo Formio, signed in October 1797, left Great Britain as the only nation to remain at war with France. However, the end of the war solved none of the underlying issues, and hostilities resumed a year later in the War of the Second Coalition. These conflicts, collectively called the French Revolutionary Wars, redrew the map of Europe and led directly into the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815).

Origins: 1789-1791

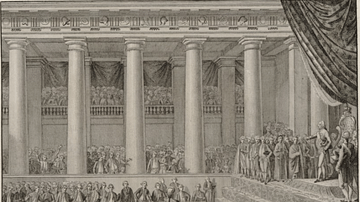

The War of the First Coalition was inextricably linked to the revolution that bore it; many revolutionaries considered it the natural progression of the French Revolution. The first clouds of war began to gather in 1789 when rampant social inequality led the three estates of pre-revolutionary France (clergy, nobility, commoners) to unite against the Ancien Régime and form a National Constituent Assembly. Attempting to reassert his authority, King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) moved 30,000 soldiers into the Paris region, which resulted in widespread riots that culminated on 14 July with the Storming of the Bastille.

Louis XVI was forced to back down, allowing the National Assembly to enact radical reforms; the August Decrees ended feudalism and other aristocratic privileges, while the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen recognized the natural rights of man. When the king refused to ratify these reforms, thousands of angry Parisians marched on Versailles and forced the king to not only accept the reforms but also return with them to Paris, where he was kept in the Tuileries Palace as a virtual prisoner. This event, known as the Women's March on Versailles or the October Days, effectively killed France's Ancien Régime.

Many in France were disturbed by this radical change in the status quo. Only two days after the Bastille's fall, the king's youngest brother, Comte d'Artois, led a group of French royalists in an exodus from France. Artois vowed to restore the old regime and traveled across Europe seeking military aid. Although the monarchs of Europe had been watching events in France unfold with trepidation, none of them were yet willing to intervene, and they all brushed off Artois's entreaties for help. Even if they wanted to help, most of the powers of Europe were already preoccupied; Prussia, Austria, and Russia, for instance, were in the middle of partitioning Poland, while Austria and Russia were also embroiled in a disastrous war with the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, France's distraction with its revolution kept it off the world stage, allowing the other powers to pursue their own agendas without worrying what the French might think or do.

So, as much as the European monarchs may have been disturbed by the calamities befalling the French royal family, it was against their interests to bestir themselves to help. Scorned by the great powers, Artois and his followers were forced to seek the friendship of lesser nations and were welcomed by the prince-bishops of Mainz and Trier, where they set up counter-revolutionary courts. By 1791, these cities hosted as many as 20,000 French émigrés, who began organizing into military units. Although the French émigré army was not powerful enough to invade France, its presence so close to the French border was not something the revolutionaries could ignore.

Escalation: 1791-1792

The French Revolution entered a calm stage in 1790 and early 1791 as the National Assembly diligently worked on its new constitution; for a time, it even seemed like the Revolution was over. Yet this situation profoundly changed on the night of 20-21 June 1791 when Louis XVI fled Paris. After two years of pretending to support the Revolution, the king showed his true colors by leaving a letter denouncing the movement before attempting to escape to the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium). The attempt, known as the Flight to Varennes, failed, and Louis XVI was escorted back to Paris. The event shook the nation to its core, as the king had proven he could not be trusted. A serious republican movement began to take root in Paris, and the revolutionaries themselves became bitterly divided.

This sudden veer toward radicalism became too much for the European powers to ignore. In August 1791, the monarchs of Austria and Prussia jointly issued the Declaration of Pillnitz, which threatened France with military invasion should any harm come to the royal Bourbon family. This declaration, unsupported by any other monarchs, was intended only to intimidate the revolutionaries, and neither signatory ruler wished to have to back up their threats with action. However, the declaration had the opposite of its intended effect. The French had long feared foreign intervention to crush their revolution, and many viewed Pillnitz as proof that this was indeed the intention of the old regimes.

In late 1791, a faction called the Girondins rose to power in the French Legislative Assembly. Led by the firebrand Jacques-Pierre Brissot, the Girondins called for war as the only means to preserve the revolution and expand it into the corners of Europe. This was widely supported, even by the king himself, who secretly hoped to use the war to restore himself to his full powers, and the Assembly began raising three volunteer armies. There was pushback from an anti-war faction in the Jacobin Club led by Maximilien Robespierre, who cautioned that the war would only result in dictatorship and the end to the Revolution, warning that, "liberty cannot be exported on the points of bayonets" (Blanning, 164). The Girondins had grabbed hold of public opinion, and in December 1791, France issued an ultimatum to Mainz and Trier, ordering them to expel the émigrés or face invasion. The prince-bishoprics complied, much to the Girondins' disappointment.

The Girondins next directed France's anger toward Austria, a traditional rival who represented everything wrong with Ancien Régime monarchies; its ruler, Emperor Francis II, was nephew to the hated French queen Marie Antoinette. Relations between the two nations deteriorated until 20 April 1792 when the Legislative Assembly voted overwhelmingly to declare war.

Brunswick's Invasion: April-October 1792

Brissot and his allies had promised an easy war, reasoning that the enslaved soldiers of despotic Europe would throw down their weapons before the liberated citizen-soldiers of France. The French were in for quite a wake-up call when their undertrained and undersupplied forces were swatted aside by the Austrians in the first weeks of the war. The initial skirmishes at Quiévrain and Marquain were humiliating for the French military – disasters made even worse when one of the defeated French armies mutinied and murdered its commanding general, Théobald Dillon. Morale worsened further when one of the top French generals, Marquis de Lafayette, fled his post and was arrested by the Austrians en route to the United States.

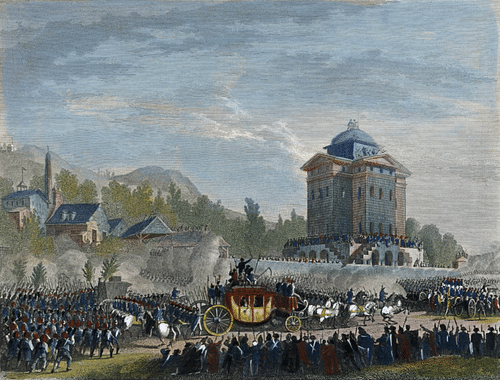

Prussia, meanwhile, joined the war on Austria's side in June and began preparing an invasion force near Koblenz. Under the command of Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, the army commenced its invasion of France the next month; however, an outbreak of dysentery and Brunswick's cautious nature slowed the invasion to a crawl. On 25 July, the invading army issued the Brunswick Manifesto, which declared its intent to restore Louis XVI to his full powers and threatened death to anyone who dared resist; like the Declaration of Pillnitz, the manifesto backfired. Fearing the wrath of the Prussians, thousands of panicked Parisians stormed the Tuileries Palace on 10 August 1792, resulting in 800 deaths as the rebels battled the Swiss Guards. After the battle, Louis XVI and his family were imprisoned.

The Prussians continued their advance, seizing the key fortresses of Longwy on 23 August and Verdun on 2 September, which opened the road to Paris; this news was again met with hysterical violence in Paris, where 1,100 people were butchered in the September Massacres. However, the news was also met with a fresh determination by the French to defend their capital, as leaders like Georges Danton urged volunteers to the front, promising that with "boldness, again boldness, forever boldness, France will be saved!" (Bell, 130). On 20 September 1792, a French army under generals Dumouriez and Kellermann halted the invaders at the Battle of Valmy; though it was only a minor battle, it disheartened the Prussians, who were still ravaged by dysentery and never desired war in the first place. Dumouriez allowed Brunswick to retreat and sent news of the victory to Paris; the next day, the ecstatic revolutionaries declared the French Republic.

War & Terror: 1792-93

The so-called 'miracle at Valmy' portended good fortunes for the French on all fronts. In the north, General Dumouriez invaded Belgium, defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Jemappes (6 November), and soon, he was in control of the whole country. In the Rhineland, an army under General Custine captured Speyer, Worms, and Mainz, and in the south, the French occupied Savoy and Nice from the Sardinians. The French Republic adopted an increasingly bellicose stance; in November, it closed the Scheldt River in direct violation of the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia and issued the Edict of Fraternity, which promised French aid to any oppressed peoples, essentially an open invitation for any European people to rebel. Finally, fiery French leaders like Brissot and Danton began calling for France to keep expanding until it had reached its 'natural borders' at the banks of the Rhine.

On 21 January 1793, the trial and execution of Louis XVI horrified the rest of Europe, with British prime minister William Pitt calling it, "the foulest and most atrocious act the world has ever seen" (Schama, 687). Britain began mobilizing its military, but France beat it to the punch, declaring war on Britain, Spain, and the Dutch Republic in February. Shortly thereafter, the anti-French coalition was joined by Portugal, Naples, and the Holy Roman Empire. The French immediately saw reversals in their fortunes.

Dumouriez was defeated at the Battle of Neerwinden (18 March 1793) and was pushed out of the Low Countries; shortly thereafter, he dealt the Republic another blow by defecting to the Austrians. The French were pushed out of the Rhineland by the Prussians, while the Spanish crossed the Pyrenees and advanced into Roussillon. To make matters worse, a counter-revolutionary civil war, the War in the Vendée, began in March while additional provinces joined in federalist revolts a few months later; rebels seized the port city of Toulon, which contained the valuable French Mediterranean fleet, and handed both prizes over to the British. The infant French Republic, it seemed, was about to be strangled in its crib.

The French answered this existential threat with violence. The Committee of Public Safety, formed in April 1793 in answer to Dumouriez's treason, was given near-dictatorial powers in the name of state security; the Committee used this power to oversee the Reign of Terror, during which hundreds of thousands were arrested under suspicion of foreign collusion or other counter-revolutionary activity, and 30-40,000 people were killed. The Terror was extended to the armies; any officer who refused an order from the Committee or failed to achieve victory faced arrest and execution. No fewer than 84 French generals were executed between 1793-94.

The Committee's concentrated authority allowed it to enact much-needed reforms in the summer of 1793, mostly orchestrated by Lazare Carnot, nicknamed "Organizer of Victory" for his efforts. The infamous levee en masse, enacted in August 1793, called for all citizens to contribute in some way to the war effort and made all unmarried males between the ages of 18 and 25 available for conscription. By September 1794, the French armies boasted over a million men, 700,000 of whom were under arms, creating the largest military force Europe had yet seen. Carnot also reorganized the army by merging new recruits with veterans, thereby fostering discipline and training. These reforms contributed to the success of France's counterattacks.

The Coalition Unravels: 1793-96

As the French were busy reorganizing, the Allied invasions had stalled. In Flanders, the Allied army decided to besiege each of the frontier fortresses before risking an attack on Paris, which gave the French time to prepare. When this Allied army made the additional mistake of dividing its forces, the French struck, defeating it piecemeal first at the Battle of Hondschoote (7-8 September 1793), then at the Battle of Wattignies (15-16 October). The opposing forces settled into winter quarters, but the next year's fighting saw more French victories at the Battle of Tourcoing (17-18 May 1794) and, most decisively, at the Battle of Fleurus (26 June). These defeats greatly demoralized the Allies, especially the Austrians; convinced the Austrian Netherlands was no longer worth defending, the Austrians withdrew from the Low Countries, leaving the British and the now exposed Dutch Republic to fend for themselves. By the end of July, the French were back in control of Belgium and commenced an invasion of Holland. They made use of the coldest winter of the century to cross over frozen rivers, and the Dutch Republic fell in January 1795. It was replaced with the Batavian Republic, the first of the French satellite states known as 'sister republics'.

This success was mirrored by French victories elsewhere. In 1793, the Vendean rebel force known as the Catholic and Royal Army was defeated, and the Vendée region was subjected to brutal punitive measures. Likewise, the French were victorious at the Siege of Toulon, which launched the career of Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1794, the French drove the Prussians back in the Rhineland and were successful against the Spanish in the Pyrenees. The next year, both nations withdrew from the war, with Prussia recognizing French claims to the left bank of the Rhine at the Treaty of Basel (April 1795). As the Coalition unraveled, Britain continued the fight; the British won a naval action against the French in the so-called Glorious First of June, but their attempt to land an invasion force of French émigrés failed at the Battle of Quiberon (23 June-21 July 1795). In 1796, French General Lazare Hoche led a failed French expedition to Ireland. Austria also kept fighting; in 1796, the French Rhineland campaign ended in failure when two French armies were repulsed by an Austrian army under Archduke Charles.

Despite a few setbacks, the French armies were clearly ascendant, though France's treasury was running out of funds. By 1796, the Terror had long been over, and the Republic was now being run by an ineffective government called the French Directory. To keep the war going, the Directory relied on the armies to pay for themselves by living off the land of occupied territories, leading to widespread looting and destruction that would decimate the landscapes of the Rhineland and northern Italy. Victorious French generals would extort captured cities for outrageous sums of money and priceless works of art, which were sent to Paris to fill the Directory's coffers. Gone was the illusion of the French soldiers as benevolent liberators, as they had proven themselves no better than any other occupying army. Gone, too, were the days of tight governmental control on the armies; strings of consistent victories and plunder put more influence and power in the hands of the generals.

Victory: 1796-97

Napoleon's Italian Campaign was initially supposed to be a sideshow, to distract the Austrians from the main thrust toward Vienna through Germany. Although the Rhineland campaign failed spectacularly, Bonaparte made up for it with the brilliance of his war in Italy; beginning with the Battle of Montenotte on 12 April 1796, Bonaparte separated the armies of Piedmont-Sardinia and Austria and defeated each in turn. He forced Sardinia to accept peace in May before capturing Milan and laying siege to Mantua.

Bonaparte resisted several Austrian attempts to relieve the siege of Mantua and won famous victories such as the Battle of Arcole (15-17 November) and the Battle of Rivoli (14 January 1797). He established several sister republics in Italy and looted cities of their priceless works of art. As his star continued to rise, Bonaparte paid less heed to the Directory in Paris. Once Mantua fell in February 1797, Bonaparte advanced toward Vienna, coming within 100 miles of the city before the Austrians asked for an armistice in April. This was followed by the Treaty of Campo Formio, signed on 17 October 1797, in which Austria exited the war, leaving Britain as the only nation to remain at war with France. The First Coalition had finally collapsed.