The fall of the Girondins, which occurred during the Paris insurrections of 31 May-2 June 1793, marked the end of a bitter power struggle between the Girondins and the Mountain during the French Revolution (1789-99). It was significant for ensuring the dominance of the Jacobins over the Revolution, and for leading into the period of the Reign of Terror (1793-94).

The Gironde & the Mountain

In the weeks following the trial and execution of Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792), two groups vied for supremacy within the National Convention, the legislating body of the First French Republic. Neither was a political party in the modern sense, but a loose coalition of deputies who voted together and worked toward similar goals. Loyalty to these groups was fluid, with some individuals fluctuating between them. However, this did not lessen the rivalry between them, a mutual hatred that would blossom into a life-or-death struggle.

Although they would have been considered extremists in most of Europe, the Girondins were by this point the Revolution's moderate faction. Named for the Gironde department in France, from which their most prominent leaders came, the Girondins had dominated the Revolution since October 1791 and had done more than anyone else to guide the nation into the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). Unsatisfied with the Constitution of 1791, the Girondins had ensured the continuation of the Revolution at a point when many had assumed it would naturally end and had played a large role in the weakening of the monarchy and the establishment of the Republic.

Yet, once they achieved the apex of power, the Girondins took a more moderate stance, opposing the radical consequences that had resulted from their actions. As historian R. R. Palmer points out, the Girondins had been the war party in 1792 but opposed the growth of wartime regulations in 1793; they had been among the first to attack constitutional monarchy but decried the execution of the king; they had used political violence when it suited them but now denounced it as radicalism. Indeed, by February 1793, the Girondins were the ones advocating for ending the Revolution before it became too extreme, believing that too much of France's destiny was being decided by the population of Paris alone. They believed in the merits of a free market and garnered most of their support from the French departments. The most prominent Girondins in early 1793 included Jacques-Pierre Brissot, Pierre Vergniaud, Marguerite-Élie Guadet, Jean-Marie Roland, and his wife, referred to as Madame Roland.

Opposing them was the Mountain, the radical leftist group which had come to dominate the Jacobin Club, to which the Girondins no longer came. Named for their tendency to sit near the top of the bleachers in Convention meetings, the Mountaineers were characterized by their populist policies which pandered to the desires of Paris' working class. The Mountain believed that what was best for the city's urban poor was best for all of France and prided itself as the mouthpiece of Paris' disenfranchised. Having arisen in late 1792 in opposition to the Girondins, the Mountain was itself fractured into multiple factions of varying extremism, which were centered around Maximilien Robespierre, Georges Danton, Jean-Paul Marat, and Jacques-René Hébert.

Of course, both groups were at the mercy of the people of Paris themselves. Organized into 48 sections, the city's lower classes had largely stayed out of the way during the early years of the Revolution, letting their bourgeois representatives draft egalitarian reforms in their name. Yet, by 1793, the reforms had not improved their situation as much as revolutionary leaders might have claimed. Unemployment was still high, inflation was worsening by the day, and the people were just as hungry under the Republic as they had been under the old regime.

Frustrated by this and made fearful by the threats from France's wartime enemies, the city's working classes had finally been spurred to action. Calling themselves sans-culottes (literally, without silk breeches), they had played a vital role in the monarchy's overthrow and had been at the center of the calls for the king's head. Although the Mountain claimed to speak for them, it was abundantly clear that the sans-culottes were not afraid to take matters into their own hands. They watched the Revolution closely, sharpening their pikes and waiting for the next moment of insurrection.

Children of Saturn

The Gironde and the Mountain argued bitterly over the fate of King Louis XVI of France. After his deposition in the Storming of the Tuileries Palace, the Girondins had wished to keep him imprisoned, as a valuable political pawn and hostage. Backed by the sans-culottes, the Mountain took a more belligerent stance; the king, they argued, could not be forgiven for his crimes, and had to die to ensure the Republic's survival. Some Mountaineers, such as Robespierre and his young protégé Louis-Antoine Saint-Just, argued that Louis XVI should be executed without even the benefit of a trial. In the end, although a trial was held, the former king was condemned to die by guillotine. His execution on 21 January 1793 pitted the factions further against one another, beginning a political tug-of-war that would directly lead to the Reign of Terror.

The next big argument began in February when starving sans-culottes raided the city's groceries for their overpriced goods. This sparked debate in the Convention over the idea of a fixed price on bread, referred to as le maximum. While the Mountain supported the idea, the Girondins did not, claiming it interfered with the free market and infringed on farmers' rights to set fair prices for their own produce. In response, a group of firebrand ultra-radicals known as the Enragés (or "enraged ones") denounced the Girondins as enemies of the people, whipping up a crowd of sans-culottes to attack Girondin-owned printshops and destroy their presses in early March. Partially due to this organized political violence, the Mountain was able to impose a "law of the maximum" on 4 May, placing a price control on wheat and grain.

The Girondins used this attack as evidence that Paris' sans-culottes had too much control over a Revolution that affected the whole nation, claiming that the Jacobins considered any ideas contrary to their own as tantamount to treason. The Girondins proposed dissolving the Convention and setting up a new assembly in the city of Bourges in central France. This was vigorously resisted by the Mountaineers, as it would deprive them of their power base. To discredit the Girondins, the Mountain accused them of plotting military dictatorship, citing the recent treason of General Charles-François Dumouriez, a Girondist ally who defected to the Austrians after his defeat at the Battle of Neerwinden.

On 13 March, prominent Girondin Pierre Vergniaud gave a powerful speech in which he denounced the mob violence encouraged by the Mountain, comparing the destruction of the Girondist printing presses to the burning of the Library of Alexandria. He warned of the dangers of the anarchic Parisian crowds to the survival of democracy and derided the most militant sans-culottes as "idlers, men without work," and "ignoramuses" in love with the sounds of their own voices. He concluded with a rather telling remark:

So, citizens, it must be feared that the Revolution, like Saturn, successively devouring its children, will engender, finally, only despotism with the calamities that accompany it. (Schama, 714)

Vergniaud's speech, of course, was interrupted with resounding boos by the Mountaineers in attendance. But although his speech was itself partisan, it spoke to the developing factionalism that was threatening to tear down any semblance of legality left to the Revolution.

Trial of Marat

In early April, the Convention would make three fateful decisions which would greatly affect the Girondin-Mountaineer conflict. First, on 1 April, a decree was passed that revoked all sitting deputies' immunity from prosecution. Then, on 5 April, the power of the Revolutionary Tribunal was expanded, so that it could try anyone who had been denounced by a public authority. Finally, on 6 April, the Convention established a Committee of Public Safety, a centralized committee made up of nine deputies with the task of overseeing the functions of government. Danton and some of his Mountaineer supporters were given seats, but no Girondins were put on the Committee.

With these three decrees, the stage was set for the final showdown between the factions. The inciting incident would come on 5 April, when the Mountain sent a circular to all Jacobin clubs across France, demanding the expulsion of any member who had spoken up against the execution of Louis XVI. The Girondins took this as a personal attack and decided to respond with a show of strength, by arresting a top Jacobin leader. They targeted Jean-Paul Marat, the provocative journalist who had recently been made president of the Jacobins, and who had signed the circular. Many Girondins also had personal reasons to hate Marat, who frequently barraged them with childlike insults during debates, referring to Guadet as a "vile bird' and Vergniaud as a "stool pigeon."

In mid-April, while many of the Mountaineers were away from Paris on mission, the Girondins struck. Taking advantage of their temporary majority, they passed a 19-page indictment against Marat, accusing him of inciting illegal violence in his various pamphlets and newspapers. Yet, this would almost instantly backfire. Once Marat was arrested, the Girondins became aware of his immense popularity when large throngs of supporters came to visit him in prison.

On 24 April, the day of his trial, the courtroom was packed with spectators who loudly cheered Marat's appearance, refusing to stop applauding until Marat himself asked them to quiet down so he could make his defensive arguments. He eloquently presented his defense, claiming that the statements the Girondins used against him had been taken out of context. Luckily for him, the judge had Mountaineer sympathies, and Marat was acquitted, to the great joy of the crowd which hoisted him upon their shoulders and adorned his head in laurel.

Following Marat's trial and the passage of the law of the maximum, public opinion shifted sharply against the Girondins. The Enragés, led by Jean Varlet and the radical priest Jacques Roux, were demanding the arrest of 22 Girondin leaders, deemed to be enemies of the people. Growing desperate, in mid-May, the Girondin leader Marguerite-Élie Guadet announced that a plot to overthrow the National Convention had been discovered, and a Commission of Twelve was established to investigate this threat. The Commission, comprised mostly of Girondins, moved to arrest prominent members of the Paris sections, including Varlet and the journalist Jacques-René Hébert, who was also a deputy procurer of the Paris Commune (city government). When the Commune protested these arrests, the Girondin Maximin Isnard warned it to abide by the Convention's decisions. If it dared foment insurrection, Isnard threatened that the French departments would rise up and march on Paris, destroying it so completely that "men will have to search the banks of the Seine for evidence that it ever existed" (Schama, 720).

Isnard's icy pronouncement did much to convince the Parisians of a Girondin plot. Far from intimidating them, it only drove the sans-culottes closer to insurrection. Such an act was encouraged by Robespierre, who gave a rousing call to arms in the Jacobin Club, demanding a "moral insurrection" against the corrupt deputies (Schama, 720). At his instigation, the sans-culottes accused 22 leading Girondins, including Brissot, Vergniaud, and Guadet, of being "guilty of the crime of felony against the sovereign people" (Davidson, 156). The Girondins responded by issuing their own circular accusing the Mountain of deliberately fomenting class war. Yet amidst all the finger-pointing, the powder keg had been lit, and the insurrection the Girondins had long feared began on 31 May.

The Insurrection of 31 May-2 June

Escorted by armed soldiers of the National Guard, 33 of Paris' most radical sections marched on the Hôtel de Ville, the seat of city government. Under the direction of François Hanriot, a former clerk who had been confirmed as commander of the National Guard only days before, the armed sans-culottes laid out a list of demands that included:

- the arrest of the 22 Girondins, as well as the entire Committee of Twelve

- the creation of a sans-culotte army to protect revolutionary reforms

- that the price of bread be fixed at three sous a pound

- the right to vote be provisionally reserved to sans-culottes only

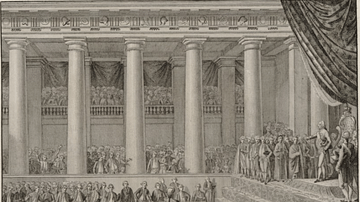

The sans-culottes received the reluctant support of the Paris Commune, after which they decided to take their demands to the National Convention itself. On the morning of Sunday 2 June, the ringing of Paris' tocsin signaled the city's sans-culottes to action. Supported by Hanriot and the National Guard, over 80,000 Parisians surrounded the Tuileries Palace, where the Convention was meeting, many of them armed.

The Girondins had been warned of the insurrection ahead of time but had refused to flee the city. Now, they sat trapped in the Convention, besieged by the sans-culottes from outside and forced to listen as Robespierre delivered a long-winded, self-righteous denouncement against them. Perhaps to mask his fear, Vergniaud interrupted Robespierre, shouting, "Conclude, then," to which Robespierre responded, "I shall conclude, and shall do so against you" (Scurr, 268).

Once Robespierre was finished, the Convention went about deciding what to do about the sans-culottes outside their doors. At first, Bertrand Barère, one of the deputies appointed to the new Committee of Public Safety, tried to defuse tensions by asking the targeted Girondins to resign from the Convention. This was unacceptable both to the Girondins in question and to the sans-culottes, who demanded nothing less than their arrests. At a certain point, the president of the Convention, Hérault de Séchelles, grew impatient; refusing to be intimidated by the rabble, he sent deputies out to meet with Hanriot, ordering him to end this charade. Hanriot's reply was both unexpected and chilling:

Tell your fucking president that he and his Assembly are fucked, and if within one hour the twenty-two are not delivered, we will blow them all up (Schama, 723).

Hanriot's threatening and foul language is quite symbolic; spoken by a common-born man and directed at a former noble, it showed who had truly come to dominate the Revolution. To prove that he meant what he said, Hanriot ordered cannons to be brought up, primed, and aimed at the Convention doors. Some nervous deputies tried to escape through other exits, only to find those, too, were blocked by Hanriot's men.

A dreadful air of silence settled among the deputies of the National Convention, broken only by the voice of the crippled deputy Georges Couthon, who spoke from his wheelchair. Attempting to save face by pretending there was a choice, Couthon announced that the will of the people had been made clear and it was the duty of the Convention to carry it out. He then read out a document of accusation against 29 deputies, including ten members of the Committee of Twelve. After the vote to arrest them carried, Vergniaud stood up, sarcastically offering the Convention a glass of blood to satisfy its thirst. The proscribed Girondins were then placed under arrest, and only then did the insurrection end.

Fall of the Girondins

For the rest of the summer and fall, the Girondins would be held under house arrest. Some of them escaped to the departments, where they hoped to foment rebellion; Marseille, Lyon, and Bordeaux had already rebelled in support of the Girondins and had cast off their Jacobin administrations. Many other prominent Girondins remained under guard in Paris, until their trial on 26 October. By then, the Reign of Terror was well underway, and the Jacobins were securely in power. Therefore, as the outcome was already decided, there was little need to go through the façade of a trial.

There were no lawyers there to defend the accused, and no documents were presented into evidence. The defendants were not even allowed to speak for themselves. On 30 October, when the guilty verdict was unsurprisingly rendered, one of the Girondins stabbed himself with a dagger and bled out on the courtroom floor. The other 21, including Brissot and Vergniaud, were brought in a tumbril to the guillotine the next day. Dramatic and defiant to the end, they sang La Marseillaise as they were executed one by one, continuing the strain until they were all dead. A week later, the Girondist Madame Roland followed her friends to the guillotine; her final words were, "Liberty! What crimes are committed in your name" (Scurr, 290).

Though the Girondins ceased to be a political force in the Convention after 2 June, it was by no means the end to their influence. Across France, the Federalist Revolts broke out in their name, and on 13 July 1793, a young woman named Charlotte Corday assassinated Marat in his bathtub, citing the fall of the Girondins as a motivation. The purge of the Girondins left the Jacobins to enjoy sole dominance of the Revolution, although this would not last. The Mountain would soon turn on itself and splinter into factions, which accused one another of counter-revolution and sent their former friends to the guillotine. The Mountain would remain at the center of bloodshed until 28 July 1794, when Robespierre, Hanriot, Couthon, and their allies were executed, bringing an end to the Terror.