The Library of Alexandria was established under the Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt (323-30 BCE) and flourished under the patronage of the early kings to become the most famous library of the ancient world, attracting scholars from around the Mediterranean, and making Alexandria the preeminent intellectual center of its time until its decline after 145 BCE.

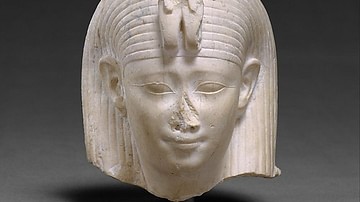

Although legend claims the idea of the great library came from Alexander the Great, this has been challenged and it seems to have been proposed by Ptolemy I Soter (r. 323-282 BCE), founder of the Ptolemaic Dynasty, and built under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (282-246 BCE), who also acquired the first books for its collection. Under Ptolemy III Euergetes (r. 246-221 BCE), the library's collection increased as books were taken from ships at port, copied, and the originals were then housed in the stacks.

Under Ptolemy IV (r. 221-205 BCE) patronage continued, and Ptolemy V (r. 204-180 BCE) and Ptolemy VI (r. 180-164 & 163-145 BCE) made acquisitions for the library such a priority around the Mediterranean that scholars began hiding their private libraries to prevent their seizure. Ptolemy V, to undercut the prestige of the Library of Pergamon, prohibited the export of papyrus – necessary for producing copies of books, and inadvertently encouraged Pergamon's parchment industry.

The final fate of the Library of Alexandria has been debated for centuries and continues to be. According to the most popular claim, it was destroyed by Julius Caesar by fire in 48 BCE. Other claims cite its destruction by the emperor Aurelian in his war with Zenobia in 272 CE, by Diocletian in 297 CE, by Christian zealots in 391 and 415 CE, or by Muslim Arab invaders in the 7th century.

As the library still existed after the time of Caesar and is referenced during the early Christian era, the most probable explanation for its fall is a loss of patronage by the later Ptolemaic rulers (after Ptolemy VIII expelled foreign scholars in 145 BCE) and uneven support by Roman emperors leading to a decline in the upkeep of the collection and buildings. Religious intolerance, following the rise of Christianity, led to civil strife, which encouraged many scholars to find positions elsewhere, further contributing to the library's deterioration. By the 7th century, when the Muslim Arabs are said to have burned the library's collection, there is no evidence that those books, or even the buildings that would have housed them, still existed in Alexandria.

Library Established

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, Ptolemy I took Egypt during the Wars of the Diadochi (Alexander's successors) and established his dynasty. He seems to have proposed the library as an extension of his overall vision for the city of Alexandria as a great melting pot, blending the cultures of Egypt and Greece, as epitomized by his hybrid god Serapis, a combination of Egyptian and Greek deities. According to the Letter of Aristeas, written between c. 180 and c. 145 BCE, the idea for the library was suggested by the Greek orator Demetrius of Phalerum (l. c. 350 to c. 280 BCE), a student of either Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE) or Aristotle's student Theophrastus (l. c. 371 to c. 287 BCE), though the authenticity of this letter has been challenged.

If Demetrius did propose the idea of a universal library, however, it would easily explain the descriptions of the building which seem to mirror Aristotle's Lyceum, specifically the colonnade in which scholars could walk and discuss various issues, though the colonnade was hardly specific to Aristotle's school. Demetrius is also said to have organized the library as a home to every book ever written and proposed the name Mouseion, a temple to the Nine Muses, for at least one part of the library (the name later serving as the origin for the English word "museum"). In answer to the question, "Why was a universal library built in the relatively new city of Alexandria?", scholar Lionel Casson writes:

Egypt was far richer than the lands of their rivals. For one, the fertile soil along the Nile produced bounteous harvests of grain, and grain was to the Greek and Roman world what oil is to ours: it commanded a market everywhere. For another, Egypt was the habitat par excellence of the papyrus plant, thus ensuring its rulers a monopoly on the world's prime writing material. All the Hellenistic monarchs sought to adorn their capitals with grandiose architecture and to build up a reputation for culture. The Ptolemies, able to outspend the others, took the lead. The first four members of the dynasty concentrated on Alexandria's cultural reputation, being intellectuals themselves. Ptolemy I was a historian, author of an authoritative account of Alexander's campaign of conquest…Ptolemy II was an avid zoologist, Ptolemy III, a patron of literature, Ptolemy IV a playwright. All of them chose leading scholars and scientists as tutors for their children. It is no surprise that these men sought to make their capital the cultural center of the Greek world. (32-33)

Head Librarians & Organization

The Mouseion and an addition, the Royal Library, were constructed under Ptolemy II, and the first librarian was the scholar Zenodotus (l. 3rd century BCE). The head librarians who followed him during the Ptolemaic Period included, in order:

- Apollonius of Rhodes (l. 3rd century BCE)

- Eratosthenes (l. c. 276-195 BCE)

- Aristophanes of Byzantium (l. c. 257 to c. 180 BCE)

- Apollonius "maker of forms" (dates unknown)

- Aristarchus of Samothrace (l. c. 216 to c. 145 BCE)

Although often cited as a librarian at Alexandria, Callimachus of Cyrene (l. c. 310 to c. 240 BCE) never held that position. He was, however, responsible for developing the early bibliographical system of Zenodotus into what today would be called a 'card catalog' of the library's holdings. Callimachus' Pinakes ("Tablets" – full title: Tables of Persons Eminent in Every Branch of Learning Together with a List of Their Writings) was a comprehensive survey and catalog of all extant Greek works that filled 120 books and created the paradigm for the library's organizational system going forward. Casson writes:

What made such a project possible was the existence of the library of Alexandria, on whose shelves all these writings, with rare exceptions, were to be found. And there is general agreement that the compilation grew out of, was an expansion of, a shelf list of the library's holdings that Callimachus had drawn up. The Pinakes has not survived; however, we have enough references to it and quotations from it in scholarly works of later centuries to provide a fair idea of its nature and extent. (39)

The works cataloged by Callimachus were not housed in a single building but in a complex of structures in the palace quarter (the Bruchion) of the Greek district of the city. The library complex seems to have resembled a modern-day university with living quarters, communal dining halls, classrooms for instruction, reading rooms, the library's stacks, laboratories, observatories, scriptoriums, lecture halls, landscaped gardens, and, perhaps, a zoo. During the Ptolemaic Period, only male scholars received patronage to live at the library with free room and board; it is unclear whether female scholars, though not allowed to live there, could make use of the library's resources, said to include 500,000 works on every subject anyone had ever written on.

Operations & Acquisitions Under the Ptolemies

The number of books the library held, and who had access to them – like much of the information relating to the Great Library of Alexandria – is unclear. The number 500,000 is most commonly cited, but this may have been an exaggeration. Casson, who more or less agrees with that number, comments:

The rolls in the main library totaled 490,000, in the "daughter library", 42,800. This tells us nothing about the number of works or authors represented, since many rolls held more than one work and many, as in the case of Homer, were duplicates. Nor do we know what was the division in function between the two libraries. The main library, located in the palace, had to be primarily for the use of the members of the Museum. The other, in a religious sanctuary with more or less unrestricted access, may well have served a wider group of readers. Perhaps that is why its holdings were so much smaller: they were limited to works, such as the basic classics of literature, that the general public would be likely to consult. (36)

The library, beginning with Ptolemy I, was funded by the royal house. The scholars, scientists, poets, literary critics, writers, copyists, linguists, and others accepted as members of the Mouseion lived there tax-free, rent-free, and were provided meals and some token salary for life. The purpose of this patronage was to allow for the greatest minds of the time, freed from the distractions of daily life, to devote themselves to study, writing, and teaching. Every scholar housed at the Mouseion was expected to teach in some capacity and give lectures; although precisely who was allowed to take classes or attend lectures is unclear.

The head librarian was appointed by the royal court and served for life. During the Ptolemaic Period, each head librarian was a scholar of note who had made some original contribution to his field of knowledge. In the case of Zenodotus, he was the first to establish an authoritative version of the works of Homer and also the first to implement an alphabetical system of organization to a library's holdings. Apollonius of Rhodes was famous for his epic poem Argonautica on Jason and the Argonauts. Eratosthenes was the first to calculate the circumference of the earth and make a map of the known world.

In addition to the librarians, there were the famous scholars who lived and worked there including the mathematician Euclid (l. c. 300 BCE), the anatomist Herophilus, the inventor and engineer Archimedes of Syracuse (l. 287-212 BCE), the physicist Strato, the grammarian Dionysius Thrax, and the innovative writer and poet Istros the Callimachean (a student of Callimachus) among many others. These scholars created their own works and had thousands of others for reference within reach, thanks to the acquisition policy of the Ptolemies. Casson comments:

The policy was to acquire everything, from exalted epic poetry to humdrum cookbooks; the Ptolemies aimed to make the collection a comprehensive repository of Greek writings as well as a tool for research. They also included translations in Greek of important works in other languages. The best-known example is the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Old Testament. Its prime purpose was to serve the Jewish community, many of whom spoke only Greek and could no longer understand the original Hebrew or Aramaic, but the enterprise was encouraged by Ptolemy II, who no doubt wanted the work in the library. (35-36)

To acquire the library's collections, book agents were sent out to purchase any works they could find. Books were confiscated from ships that docked in Alexandria's harbor, copied, and the originals kept in the library; the copies were given to the owners. Older works were the most coveted on the grounds they had not been extensively copied and so contained fewer scribal errors. According to Casson, this created a new black-market industry: forging "old" copies for sale at high prices (35). Famous works were also a premium. Ptolemy III is said to have posted the exorbitant bond of 15 talents (approximately $15 million or more) to Athens to borrow the original manuscripts of Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles to copy, promising to return them. After he had them copied on high-quality papyrus, he sent the copies to Athens, kept the originals, and told the Athenians they could keep the money.

The acquisition policy of the Ptolemies was mirrored by the kings of the Attalid Dynasty (281-133 BCE) who needed books for the Library of Pergamon, the rival of the Library of Alexandria. During the reign of the Attalid king Eumenes II (r. 197-159 BCE), Ptolemy V prohibited the export of papyrus to prevent Pergamon from making copies of books. All this did, however, was launch Pergamon's parchment industry. The English word "parchment", in fact, comes from the Latin pergamena – "paper of Pergamon" – as parchment came to replace papyrus as writing material.

Decline & Claims of Destruction

The Library of Alexandria began to decline under Ptolemy VIII (r. 170-163/145-116 BCE), a scholar who had written on Homer and supported the patronage of the library, but who withdrew his support after the power struggle with his brother Ptolemy VI and, in punishing those who had sided with his opponent, banished all foreign scholars from the city. Among these was the head librarian Aristarchus of Samothrace who fled to Cyprus in 145 BCE and died soon after. Ptolemaic patronage of the library then flagged, and the position of head librarian was no longer given to an eminent scholar but was awarded to political cronies. It is probable that, when they were expelled from Alexandria, the banished scholars took books with them but, even if they did not, the texts had been standardized and copied by this time and would have existed in private libraries and in the collections of other intellectual centers such as Athens and Pergamon.

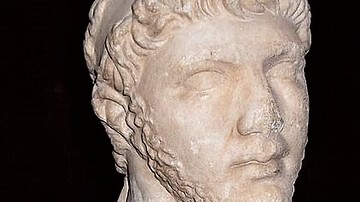

The Ptolemaic Period ended with the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE, and during the Roman Period that followed, patronage of the library was uneven at best. The Roman emperor Claudius (r. 41-54) patronized the library, as did Hadrian (r. 117-138), but whether any others did is unclear. In 272, when Aurelian retook Alexandria from Zenobia, who had claimed it as part of her Palmyrene Empire, the library's district was destroyed, though it is unknown whether the buildings that once constituted the library survived. In 297, emperor Diocletian also leveled that section of Alexandria and, most likely, this would have been when whatever was left of the library was destroyed. By this time, however – as noted – Alexandrian scholarship was already a memory. Whatever great work had gone on in the city had been taking place elsewhere since sometime after 145 BCE.

All of this seems certain but that has not stopped writers from repeating the claim that the Great Library of Alexandria, which housed all the knowledge of the ancient world, was burned either by Julius Caesar in 48 BCE, by the Christians in 391 (or, perhaps, in 415 around the time of the murder of Hypatia of Alexandria), or by the Muslims in the 7th century. Whatever was burned in the fire started by Caesar in 48 BCE, it was not the library because that institution is referenced by later writers. Mark Antony, according to Plutarch, gave the entire collection of 200,000 books from the Library of Pergamon to Cleopatra VII in 43 BCE for the library; so, clearly, a library still existed in Alexandria after Caesar's death in 44 BCE. Augustus Caesar (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) is said to have later given some, though not all, of the books back to Pergamon.

In 391, Theophilus, Bishop of Alexandria, supervised the destruction of the Temple of Serapis, which had housed a part of the library's collection, but whether any books were still kept there is unknown. Alexandria had increasingly become hostile to the kind of inclusive scholarship the library had encouraged since the rise of Christianity in the city after 313. By 391, civil unrest fueled by religious intolerance had become the hallmark of the city. It seems certain that the Serapeum (Temple of Serapis) was destroyed at this time, and a church was built on its site, but there is no evidence of the destruction of the library; probably because it had already been destroyed by Aurelian or Diocletian.

The claim that the Muslim Arabs under Caliph Umar destroyed the library in 641 is completely untenable. The famous story of Umar ordering the burning of the vast collection, saying that, if the works agreed with the Quran, they were superfluous, and if they contradicted the Quran, they were heresy, appears 600 years later in the work of the Christian writer Gregory Bar Hebraeus (l. 1226-1286) taken from earlier 13th-century Muslim Arab authors such as Ibn al-Qifti. This account has been dismissed by scholars as fiction since the 18th century.

Conclusion

The claim that the loss of the Library of Alexandria in a great conflagration turned the knowledge of the ancient world into smoke and set humanity's intellectual development back thousands of years is a fable that has become increasingly accepted through repetition in articles, books, television shows, documentaries, videos, and assorted pamphlets blaming one party or another for the destruction of the library to advance a given agenda.

The image of the Great Library of Alexandria, and all the knowledge of the ancient world, going up in flames is certainly more dramatic than the more mundane scenario of the library declining due to neglect fostered by petty political intrigue and a changing socio-political-religious zeitgeist, but the latter is almost certainly what actually happened. There is no question that written works were destroyed in 48 BCE and after, but this does not mean that all the books housed in the library at its zenith were lost. As noted, copies were made of the collection, and these departed Alexandria with their owners.

Alexandria may have been able to boast of the greatest library in the ancient world under the early Ptolemies, but no account from antiquity supports the claim that the library was still a great intellectual center by the Roman Period. It is clear, from references in the works of various ancient writers, that a considerable number of manuscripts were lost at Alexandria between c. 48 BCE and 415 CE, but what these were is unknown. Many of the works referenced as part of the library's collection still exist today all over the world and form part of the collection of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina ("Library of Alexandria"), opened in 2002 in Alexandria, Egypt, as an homage to the great library of antiquity.