The Battle of Fleurus (26 June 1794) was the climax of the Flanders Campaign of 1792-95 and was one of the most decisive battles in the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797). A French victory, Fleurus ensured French ascendency for the rest of the war, leading to France's conquest of Belgium and to the destruction of the Dutch Republic.

The battle involved the French Armée de Sambre-et-Meuse, a newly created army of 75,000 men under the command of General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, and a Coalition army of 52,000 men commanded by Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. Though the battle itself was tactically indecisive, its consequences would profoundly change the course of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). It led to the breakup of the Coalition army, as the defeat convinced the Habsburg monarchy to evacuate the Low Countries in the belief that the defense of the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium) was a lost cause.

Consequently, the French were able to conquer Belgium and push into Holland; by January 1795, the Dutch Republic had been dismantled and replaced by the Batavian Republic, the first of the pro-French 'sister republics'. Fleurus also indirectly helped lead to the end of the Reign of Terror in the ongoing French Revolution (1789-1799), as subsequent French military victories invalidated the justification for the Terror.

Armée de Sambre-et-Meuse

The French victory at the Battle of Tourcoing (17-18 May 1794) led to a power shift in the Flanders campaign as the Coalition army was forced on the defensive. The morale of the Allied army, already negatively impacted by the defeat itself, worsened on 30 May when the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II abandoned the army and returned to Vienna. The defeat at Tourcoing had convinced Francis II and his ministers that the defense of the Austrian Netherlands was a lost cause; the emperor was much more interested in the upcoming third partition of Poland and began siphoning off officers and men from the army in Flanders for redeployment in the east. Of course, Austria's loss of interest in continuing the fight in the Low Countries was seen as a betrayal by other Coalition nations like Great Britain and the Dutch Republic, who had more at stake in the region.

The French, meanwhile, were preparing to push into Belgium. Just as the Coalition army was left disheartened and depleted after Tourcoing, the French were in high spirits, their armies swelling with new recruits. By late May 1794, there were 227,000 French troops in the Flanders region, but for the sake of efficiency, 96,000 of them were reorganized into a new army dubbed the Armée de Sambre-et-Meuse under the command of General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan. Jourdan, despite his new command, was already on thin ice; he had been forced into retirement the previous January for refusing to follow the orders of the Committee of Public Safety, the de facto government of the French Republic. Jourdan had been saved from execution only by the intervention of a representative-on-mission who vouched for his character. Now, he was being given a second chance; however, should he disappoint again, Jourdan could expect no such salvation. In Paris, the Reign of Terror was at its zenith, and the guillotine was hungry for disgraced military officers. A defeat would likely cost Jourdan his head.

By the time Jourdan took command in early June, the French had crossed the Sambre River three times but had been repulsed each time. On 12 June, Jourdan led his newly created army over the river for a fourth time and besieged Charleroi, considered a key Belgian fortress by both sides. On 16 June, William V, Prince of Orange, and 43,000 Anglo-Dutch soldiers arrived to relieve the siege; in the ensuing Battle of Lambusart, the Allies surprised the French by emerging from the heavy mists in which they had been concealed. After losing 3,000 casualties, the French were chased back across the Sambre. The French may have been defeated, but they were not broken; they had retreated in an orderly fashion and were eager to try again. So, on 18 June, only two days after their defeat, the Armée de Sambre-et-Meuse followed Jourdan across the Sambre yet again. The French had tasted victory, and defeat was not an option.

Third Siege of Charleroi

The Prince of Orange, feeling confident in his victory, was certain the enemy had been decisively beaten and would not be foolhardy enough to cross the Sambre a fifth time. When Jourdan proved him wrong after a mere two-day respite, Orange was shocked, but still could not believe the French were mad enough to attack Charleroi again; surely, he reasoned, they were headed for Mons instead. Following this logic, Orange pulled back to defend the road to Mons, allowing the French to approach Charleroi unopposed. Utilizing 75,000 of his men, Jourdan invested the fortress for a third time on 19 June, and the siege progressed quickly as the French made use of the trenches and siegeworks they had constructed in their first two attempts.

A few days into the siege, the Armée de Sambre-et-Meuse received a visitor from Paris. Louis-Antoine de Saint-Just was a fiery young Jacobin who, as a member of the Committee of Public Safety, was one of the most powerful men in France. Saint-Just had arrived to ensure the siege of Charleroi went as quickly as possible and was prepared to unleash the Terror upon the army to achieve his goal. According to historian Ramsay Weston Phipps, Saint-Just made threats to guillotine the chief engineer and even had an artillery captain shot for taking too long to assemble his battery. To his credit, Jourdan found a way to turn the young Jacobin's terrifying presence to his advantage; on 25 June, he arranged a meeting between Saint-Just and the commandant of the garrison of Charleroi.

The commandant presented Saint-Just with a letter containing his terms of surrender, to which Saint-Just coldly replied, "It is not the paper I want, but the place" (Phipps, 158). Saint-Just managed to convince the commandant that the French were closer to winning the siege than they really were, leading the commandant to surrender the fortress unconditionally. The French were so pleased with this outcome that they awarded the garrison with the honors of war, allowing them to retain their sabers and colors. For the French, the surrender came not a moment too soon. That very afternoon, an Allied army of 52,000 men arrived to relieve the siege.

Preparations

Coburg, the Allied commander-in-chief, had arrived at Charleroi under the assumption that the garrison could hold out for a few more days. To inform the garrison that help was coming, he sent some troops to the heights of Heppignies to fire rockets into the sky as a signal. However, these men were chased off by perceptive French soldiers and were forced to fire the rockets off farther to the north, where the signal was not visible to the fortress. As a result, the garrison gave in to Saint-Just's threats and surrendered the fort, unaware that help was right outside their walls; likewise, Coburg was unaware that the fortress had fallen and began planning an attack to lift the siege.

From his headquarters at Nivelles, Coburg devised a plan to envelop and destroy the French army. The brunt of his attack would be concentrated against the French right, which he hoped to overwhelm in order to get behind the French center and surround their army. Coburg entrusted the overall command of this attack to Archduke Charles, brother of the emperor, giving him seven battalions of infantry and 16 cavalry squadrons. Charles' attack, concentrated on the town of Fleurus, would be supported by 13 infantry battalions and 26 squadrons under General Johann Peter Beaulieu; Beaulieu was to turn south before reaching Fleurus in order to outflank the French line and attack from the rear. Meanwhile, Coburg ordered additional attacks on the French center and left. A column under the Prince of Orange was to seize the crossings over the river Pieton to deny the French a route of retreat.

Jourdan, meanwhile, overestimated the strength of Coburg's army, believing it to be equal to his own (around 75,000 men). He, therefore, opted to stay on the defensive, arranging his army in a semicircle. General Jean-Baptiste Kléber commanded the French left, while the all-important right flank was held by divisions under generals François Marceau and François Joseph Lefebvre.

Battle of Fleurus

By 3 a.m. on 26 June 1794, the Allied columns were in motion, descending on the French positions. By 5:30 a.m., the predawn silence around Fleurus was shattered by the crack of musket fire as Archduke Charles' column encountered Lefebvre's division. Fierce fighting in and around Fleurus was echoed further to the right, where Beaulieu's column engaged Marceau near the villages of Baulet and Velaine. Here, the Allies overwhelmed the French, and the first rays of daylight found Marceau's division gradually falling back to the forest of Gopiaux. Around 10:30, Marceau's division finally broke, as panicked men fled across the Sambre in droves. It was not until noon that Marceau succeeded in rallying his men.

The rout of Marceau's division had exposed Lefebvre's right flank. To make up the difference, Lefebvre was forced to pull out of Fleurus itself, sending three battalions under his chief of staff, Colonel Jean-de-Dieu Soult, to fill the gap in his lines between the town of Lambusart and the wood above the river. Lefebvre ordered his men to let the enemy get close without firing on them; when the archduke's men drew close, Lefebvre's men unleashed a devastating volley as a French cavalry charge chased the Allies back. In this way, Archduke Charles' men were repulsed four times. Meanwhile at Lambusart, Soult's three battalions combined with the survivors from Marceau's division to hold back Beaulieu. The fighting grew heavy around Lambusart, and Soult had five horses killed from under him; later, looking back on the battle, Soult would refer to the fight as "fifteen hours of the most desperate fighting I have ever seen in my life" (Phipps, 163).

Despite Soult's stiff resistance, Beaulieu ultimately captured Lambusart, though some stubborn French sharpshooters continued to fight from the windows of houses. Beaulieu set fire to barns and corn fields in the village in order to create a smoke screen and drive the French out; Phipps reports that as the inferno spread, "the very ground they fought on" was in flames. Meanwhile, Lefebvre refused to give an inch, and aside from the toehold at Lambusart, the Allies failed to gain any ground. Between 4 and 5 p.m., Archduke Charles received orders from Coburg to call off the attack, and the Allies began to retreat in great confusion. Lefebvre took advantage of the disorder, personally leading an attack against Beaulieu's position at Lambusart. By 6 p.m., the Allies had withdrawn from the field; the vital attack on the French right flank had failed.

Combat on the French Left & Center

Although the most dramatic fighting occurred on the French right flank, there were simultaneous actions along the French left and center. At 1 a.m., 24 battalions under the Prince of Orange began to advance against the French left but were stopped by a French division under General Montaigu at Courcelles. At 9 a.m., Montaigu pulled back across the Sambre, though he had won French General Kléber enough time to shore up defenses along the Pieton river. Throughout the rest of the morning, Kléber held the Pieton crossings against Orange's men while Montaigu defended the Sambre. At around 2 p.m., Kléber decided it was time to launch a counterattack, and several French brigades under Colonel Jean Bernadotte succeeded in pushing the Allies back. By 5 p.m., Orange realized the French defenses on the left flank were still strong and ordered a withdrawal.

At 5:30 a.m., fierce fighting commenced at the French center, where an Allied column under Prince Kaunitz grappled with a French division under Jean-Étienne Championnet for control of the heights of Heppignies. Initially, Kaunitz's attacks failed as the ground worked to Championnet's advantage. However, the rout of Marceau's division on the far right forced Lefebvre to spread his troops out more thinly which, in turn, exposed Championnet's flanks. In the early afternoon, Kaunitz launched a fierce attack against Championnet's position, causing the French to withdraw from the heights at 3:30. But when news reached Championnet of Lefebvre's success on the right, he turned around and ordered a bayonet charge to reclaim the heights. Kaunitz's men were caught offguard, having believed the fight was over, and were easily broken. Thus, by nightfall, the French proved victorious on every part of the battlefield.

Aftermath & Significance

As the battle wore on during the afternoon of 26 June, Coburg received confirmation that Charleroi had, indeed, already fallen. Dismayed, he ordered a general retreat at around 5 p.m. and chose not to continue the battle the next morning. Like his emperor, Coburg may have come to the conclusion that the Austrian Netherlands were not worth the blood being spilled in its defense. He pulled back and set up camp between l'Alleud and Waterloo. The French, exhausted and short on ammunition, did not pursue. Excluding the loss of the 2,800 man Charleroi garrison, the Allies had suffered some 5,000 casualties; French casualties also numbered around 5,000.

The Battle of Fleurus only confirmed to the Austrians that it was no longer worth the effort to hold on to Belgium. The grand Coalition army, which had once been the terror of the French revolutionaries, fell apart; Coburg led the Austrians eastward as the Anglo-Dutch elements moved to the north, to defend the Dutch Republic. Jourdan's Armée de Sambre-et-Meuse and General Jean-Charles Pichegru's Armée du Nord began a joint conquest of Belgium, completed when the French entered Antwerp and Liège on 27 July. The British and the Dutch found that they were unable to hold off the French on their own, and the French invaded Holland in August. On 18 January 1795, Dutch revolutionaries gained control of the government in Amsterdam with French support, and the Dutch Republic was destroyed. In its place, the Batavian Republic was proclaimed as a 'sister republic' of France.

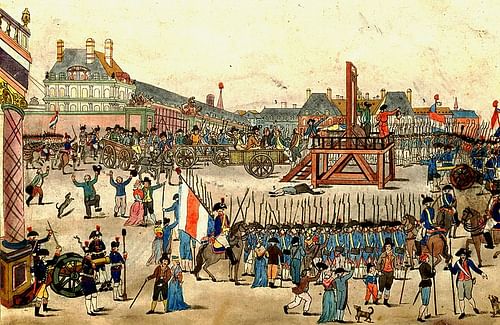

Fleurus was a decisive moment in the French Revolutionary Wars, but it also helped end the Reign of Terror. Saint-Just returned to Paris covered in glory to announce that a great victory had been won. But victory at Fleurus seemed to invalidate the Terror and the quasi-dictatorship of the Committee of Public Safety, which were meant to protect the French Republic from its enemies. With the destruction of Coburg's army and the conquest of Belgium, the Republic was no longer in immediate danger. Regardless, the Terror showed no signs of stopping, causing many in France to become suspicious of the Committee's true intentions. These factors contributed to the fall of Maximilien Robespierre on 9 Thermidor Year II (27 July 1794) and the subsequent Thermidorian Reaction; Saint-Just was among the allies of Maximilien Robespierre who were executed in the coup.

Finally, Fleurus was also significant for being the first battle in history to utilize aerial reconnaissance. The French reconnaissance balloon, l'Entreprenant, was tethered to a 190 m tall hill, the highest point on the battlefield. From this vantage, the crew of the balloon was able to observe enemy troop movements which were then reported back to Jourdan. Multiple French officers at the battle, including Soult, would later claim the balloon provided no helpful information and was useless; even so, the use of the balloon was still notable for attempting something never before done in warfare.

Conclusion

The Battle of Fleurus may not be as well-remembered as Napoleon's Italian Campaign or the Battle of Valmy, but it deserves mention among the most important battles of the French Revolutionary Wars. As mentioned above, it greatly impacted the outcome of the War of the First Coalition and helped change the course of the French Revolution by contributing to the end of the Terror. Moreover, many French commanders who would achieve fame during the First French Empire (1804-1814; 1815) gained experience at Fleurus; Jourdan, Lefebvre, Soult, and Bernadotte each played important roles at Fleurus and would each one day earn renown as one of Napoleon's marshals. Like these marshals, the battlefield itself would return to play a role in the story of Napoleon Bonaparte; the Battle of Ligny, fought in 1815 during the Waterloo campaign, took place on the same field as Fleurus.