The War of the Second Coalition (1798-1802), part of the broader French Revolutionary Wars, was the second attempt by an alliance of major European powers to defeat Revolutionary France. The Second Coalition, which included Russia, Austria, Great Britain, Naples, Portugal, and the Ottoman Empire, was defeated by the French Republic, and hostilities ended with the Treaty of Amiens in 1802.

Origins: Victory of the Great Nation

With the signing of the Treaty of Campo Formio on 17 October 1797, the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797) finally came to an end. Born out of tensions surrounding the French Revolution (1789-1799), the war had seen the infant French Republic take on most of the great powers of Europe, including Austria, Prussia, Great Britain, and Spain, while simultaneously dealing with several counter-revolutionary rebellions within its borders. Through draconian efforts such as mass conscription and the bloodshed of the Reign of Terror, the French Republic managed not only to survive the existential threat posed by these enemies, but to triumph; by 1796, French armies had won a succession of victories in the Netherlands, on the Rhine, and in Italy. The frustrated nations of the First Coalition gradually dropped out of the war until October 1797, when Austria made peace at Campo Formio and left Great Britain as the only power to remain at war with France.

The victory left the French Republic as the preeminent power in Western Europe, rivaled only by Britain itself. France had annexed Belgium, Luxembourg, and the west bank of the Rhine and indirectly ruled Holland and northern Italy through a collection of client states known as 'sister republics'. For the French, who had succeeded in their war goals to both preserve their Revolution and expand it into Europe, this was not just a victory but also an indicator of the greatness of the French people. Around this time, the French increasingly referred to themselves as "the Great Nation", a state superior to all others and unencumbered by international rules. This rise in nationalism coincided with a sharp turn back into extremist Jacobinism; the Coup of 18 Fructidor (4 September 1797) purged the Republic's government, called the French Directory, of its conservative and royalist members, many of whom were exiled to French Guiana. This neo-Jacobin resurgence resulted in a new wave of violence against priests and political opponents and reignited the disdain for the old regime monarchies of Europe. The new Fructidorian Directory promptly broke off preliminary peace talks with Britain and began to make plans for further territorial expansion.

At the Congress of Rastatt, which met in November 1797 to finalize the peace between France and the Holy Roman Empire, the first signs of France's aggressive post-war foreign policy became apparent. Despite Holy Roman Emperor Francis II's promise to the Imperial Diet that the empire would retain its "complete integrity", the French still compelled the German states to cede all lands on the west bank of the Rhine. The French also stipulated that German princes who lost land from the deal could be compensated by the secularization of ecclesiastical states, dealing a further blow to the unity of the empire.

The nations of Europe, unnerved by France's belligerent attitude at Rastatt, were further alarmed in January 1798, when a French-backed coup overthrew the government of Switzerland, which was replaced with a French puppet state called the Helvetic Republic. Meanwhile, a riot in Rome that led to the death of a French general was used as the pretext for the French invasion of the Papal States on 15 February 1798. The Eternal City was integrated into the patchwork of French client states as the Roman Republic, and Pope Pius VI was taken prisoner. Though the "Great Nation" was now at the center of a zone of influence that stretched in an almost unbroken line from Amsterdam to Rome, its appetite for conquest remained unsatisfied.

Egyptian Expedition

Of course, the "Great Nation" could not claim total victory over its rivals until Britain was defeated. Although France initially considered a direct invasion of Britain, this was deemed too risky. An alternative plan was proposed by the crafty foreign minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand and the popular General Napoleon Bonaparte, who suggested establishing a French colony in Egypt. Such a colony could compensate for the recent loss of France's colonies in the West Indies and could be used as a base to menace British interests in India. Although Egypt was nominally ruled by the Ottoman Empire, it was under the de facto control of the Mamluks, a military class whose rule was unpopular. The Directory approved the plan and in May 1798, a fleet of 13 ships-of-the-line, 13 frigates, and 200 transports set out from Toulon, ferrying Bonaparte's army across the Mediterranean.

After evading a squadron of British warships under Horatio Nelson, the French fleet landed at Malta on 10 June; the island was promptly captured, and the Knights of St. John were expelled. The French continued on to Egypt and occupied Alexandria on 2 July. After a dreadful march through the desert, Bonaparte defeated the Mamluks at the Battle of the Pyramids (21 July) and entered Cairo days later. Just when it seemed that Napoleon's Campaign in Egypt and Syria had been a success, Nelson caught up with the French fleet that was anchored at Aboukir Bay; the subsequent Battle of the Nile (1 August) resulted in the complete destruction of the French fleet, trapping Bonaparte's army in Egypt. In September, the Ottoman Empire formally declared war on France and began marshaling an army in Syria to reclaim Egypt.

The Second Coalition Forms

France's invasion of Egypt proved too much for the other European powers to bear; Nelson's victory on the Nile made France look weak, emboldening France's enemies to finally strike. Somewhat unexpectedly, this second anti-French coalition was spearheaded by Russia, which had remained neutral in the first coalition war. Emperor Paul I of Russia (r. 1796-1801), a great admirer of the Knights of St. John, was incensed by Bonaparte's occupation of Malta, an act that seemed to confirm Paul's suspicions that Revolutionary France would keep on expanding until it was stopped by military force. Emperor Paul sent a Russian fleet into the Mediterranean, which set about capturing the French-occupied Ionian Islands. Meanwhile, he assembled a new anti-French alliance which, by March 1799, had grown to include Britain, Austria, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, and Naples; the War of the Second Coalition had begun.

Like its predecessor, the Second Coalition suffered from poor communication between its member nations. This was evidenced on 12 November 1798, when Naples kicked off the war by invading the Roman Republic, eager to restore papal authority. In their haste, the Neapolitans acted without consulting any other Allied nation, and although they briefly occupied Rome, they were forced out again by the French on 12 December. The French advanced into Naples, forcing the Neapolitan royal family to evacuate on 22 December aboard Admiral Nelson's flagship; by January 1799, the Kingdom of Naples had fallen and was reorganized as the Parthenopean Republic, yet another French client state. The French scored another victory in Italy the same month when they annexed Piedmont after forcing King Charles Emmanuel IV of Piedmont-Sardinia to abdicate. The French now controlled all of Italy aside from Venice and Venetia. For the Allies, the war was not off to a great start.

Campaigns in Germany, Switzerland, & Italy

Despite these early victories, the French Republic was left in the precarious position of having to defend a frontier stretching from Holland to Naples. On 5 September 1798, the Directory enacted the Jourdan Law which called for the mass conscription of all unmarried males between the ages of 20-25. These conscripts were sent to the three major French armies, each positioned on a critical frontier: General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan commanded an army on the Rhine, General André Masséna commanded in Switzerland, and Barthélemy Schérer commanded the Army of Italy. They were faced with several Austrian armies consisting of a combined 300,000 men across the board; the Austrians were to wait until the arrival of 60,000 Russian reinforcements before beginning their offensive.

In Germany, French General Jourdan decided to strike before the Russians could arrive. In early March 1799, he led his army across the Rhine and through the Black Forest, until he finally caught up with an Austrian army commanded by Archduke Charles, brother of Emperor Francis. Despite being outnumbered nearly 3 to 1, Jourdan attacked on 25 March, at the Battle of Stockach, and suffered a devastating defeat. Jourdan retreated back across the Rhine and resigned his command. Archduke Charles had a chance to pursue Jourdan's army and eliminate it, thereby opening up a path into France, but inadequate supplies prevented him from doing so. By the time he finally advanced, Jourdan's old army had joined with General Masséna in Switzerland; Archduke Charles attacked them at the First Battle of Zurich (4 June) but was repelled. Despite his victory, Masséna realized he could not withstand a second assault and withdrew to a better defensive line along the Limmat River, allowing Charles to enter Zurich unopposed.

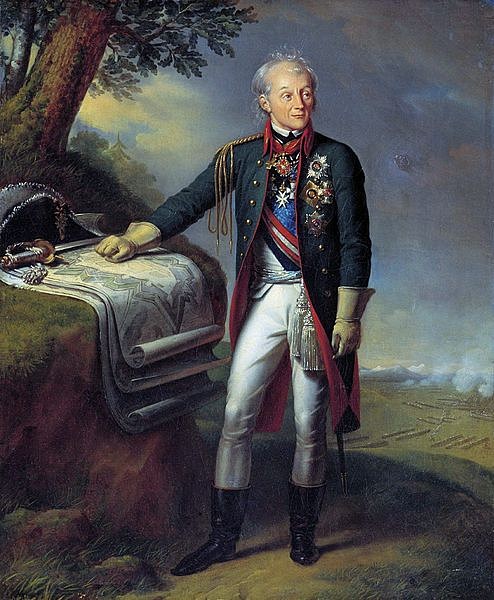

While they were being pushed back in Germany and Switzerland, the French were also losing ground on the Italian front. On 25 March, French General Schérer crossed the Mincio River with 35,000 men and attacked a 58,000-man Austrian army in a series of engagements collectively known as the Battle of Magnano (5 April). The French were defeated and retreated back across the Mincio after losing 8,000 casualties. On 15 April, the Austrian army in Italy was joined by a Russian expeditionary force led by the celebrated General Alexander Suvorov, who had been appointed as the commander-in-chief of all Allied armies. Suvorov's Austro-Russian army crossed the Adda River and dealt the French a stinging defeat at the Battle of Cassano (27 April). The next day, General Schérer was removed from the French command and replaced with Jean-Victor Moreau, as Suvorov entered Milan unopposed.

Moreau decided to fall back to Genoa and issued orders for another French army under General Jacques Macdonald to march north and link up with him; Suvorov intercepted and decisively defeated Macdonald at the Battle of Trebbia (17-19 June). This was the high watermark of Suvorov's Italian campaign; like Archduke Charles, he was now presented with a chance to annihilate the broken French armies and press on into France. But Suvorov, too, was hindered, this time by the politicians in Vienna, who ordered him to finish conquering Italy. Suvorov dutifully laid siege to Mantua, which capitulated on 28 July, and conquered Piedmont, but this only led him to butt heads with the politicians in Vienna a second time. Suvorov and his patron Emperor Paul wanted to liberate the Italian territories they conquered and restore Italy to its pre-war borders. The Austrians, on the other hand, wanted to keep the occupied territories such as Piedmont under the administration of military governors until after the war; since the bulk of the fighting was being done by Austrian troops, the Austrians felt entitled to annexing Italian lands. Vienna ended up ordering Suvorov to cross the Alps and join Archduke Charles' campaign in Switzerland to remove his meddling presence from Italy. It was a slight that the Russians would not soon forget.

Anglo-Russian Invasion of Holland

Meanwhile, the British and Russians decided to take some of the pressure off the wars in Switzerland and Italy by opening another front in the Low Countries. On 27 August 1799, the Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland began when an Allied army landed at Den Helder, led by Prince Frederick Augustus, Duke of York and Albany, the second son of King George III. York's goal was to dismantle the French client state known as the Batavian Republic and restore the Prince of Orange to power in Holland. However, York's advance was stymied by flooded terrain, rampant disease, and inadequate food supplies, and he received none of the expected support from the Dutch population. York was defeated by a Franco-Dutch army first at the Battle of Bergen (19 September), then at the Battle of Castricum (6 October). Realizing the campaign had failed, York signed the convention of Alkmaar which allowed the British and Russian soldiers to evacuate Holland.

Suvorov Crosses the Alps

On 4 August 1799, General Barthélemy Joubert arrived in Genoa to take command of the French Army of Italy. Having promised the Directory a swift victory, Joubert went on the offensive and met Suvorov's army at the Battle of Novi (15 August). Joubert was killed early in the battle, and the French were once again forced to retreat after a staggering loss of 11,000 men. It was to be Suvorov's last victory in Italy, as he now prepared to begin his treacherous cross over the Alps. He arrived at Taverne on 15 September to find none of the 1,400 mules that the Austrians had promised to provide to transport his army's equipment over the mountains. Suvorov was forced to waste precious time as he procured the pack animals himself. His army finally set off on 19 September, reaching St. Gotthard Pass four days later; here, the Russians met heavy resistance from French skirmishers, but they still pressed on.

The Russians passed through the so-called 'Devil's Hole', a 180-meter (c. 200 yds) tunnel where they made easy targets for the French sharpshooters. Then, they came to the 'Devil's Bridge', a narrow crossing high above the icy Reuss River defended by the French; aided by Austrian sappers, the Russians forced the crossing but paid a hefty price in casualties. After this intense journey, Suvorov finally made it to Altdorf on 26 September, where he planned to link up with General Friedrich Hotze's Austrian army for a coordinated attack on the French positions. Little did Suvorov know, that on the same day he arrived at Altdorf, the Allied army in Switzerland was busy fighting Masséna's French army at the Second Battle of Zurich (25-26 September). The battle resulted in a crushing Allied defeat and the death of General Hotze. When Suvorov heard the news, he apparently burst into frustrated tears. Knowing his ragged and starving army stood no chance against Masséna's troops, Suvorov made the difficult decision to retreat.

Marengo

As 1799 ended, France was in a much better position than at the beginning of the year, thanks to the victories in Holland and Switzerland. But the earlier humiliating defeats were still fresh in the public's mind, and the Directory was blamed; across Paris, several plots were being hatched to overthrow the ineffective Directory. It was in this political situation that Napoleon Bonaparte fatefully arrived in October 1799 – with the failure of his Egyptian expedition, Bonaparte had abandoned his army in Alexandria. Conspiring with Talleyrand and Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès, Bonaparte seized control of the government in the Coup of 18 Brumaire (9 November 1799) and established the French Consulate, with himself as First Consul.

In the spring of 1800, First Consul Bonaparte sent General Moreau to take command of the army in Germany and decided to take charge of the Italian theatre of war himself. After raising a new army at Dijon, Bonaparte crossed over the Alps in May and fought the Austrians at the Battle of Marengo on 14 June; it was a hard-fought battle, and Bonaparte only narrowly produced a victory. The Austrians were dealt a second blow when Moreau invaded Bavaria and beat them at the Battle of Hohenlinden (3 December 1800). These two defeats led Austria to sue for peace. The Treaty of Lunéville, signed between Emperor Francis II and the French on 9 February 1801, brought Austria out of the war.

Peace of Amiens

Emperor Paul blamed his allies for the defeats of late 1799; disgusted at the Austrians' ambitions to annex Piedmont, he was equally frustrated with the poor performance of York in Holland. On 8 January 1800, Paul recalled Suvorov and ended his alliance with both Britain and Austria. Paul reconciled with the French and even considered invading British India as part of a Franco-Russian alliance; such plans were put to rest when Emperor Paul was assassinated on 23 March 1801. Though the alliance with France did not materialize, Paul's successor, Emperor Alexander I of Russia (r. 1801-1825), formalized peace with France in October 1801.

The British, however, were determined to keep fighting. On 21 March 1801, an Anglo-Ottoman force defeated the remnants of Bonaparte's Egyptian army at the Battle of Alexandria and captured the city after a siege six months later. Meanwhile, Britain attempted to blockade France by seizing neutral ships that were trading at French ports. To enforce free trade, Emperor Paul had set up a League of Armed Neutrality that consisted of Denmark, Sweden, Prussia, and Russia. In response, the British assembled a fleet with the goal of breaking up the League and attacked the Danish fleet at the First Battle of Copenhagen (2 April 1801). The Danes agreed to the British terms after they received news of Emperor Paul's assassination, which meant the end of the League of Armed Neutrality.

On 25 March 1802, the British and French made peace at the Treaty of Amiens. The Ottoman Empire, now the last remaining member of the coalition, made peace on 25 June 1802 and regained control of Egypt. This marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars as well as nearly a year of peace; the resumption of hostilities in May 1803 is often considered the start of the Napoleonic Wars.