The Battle of the Pyramids (21 July 1798), or the Battle of Embabeh, was a significant battle fought during Napoleon's Campaign in Egypt and Syria. On a battlefield 15 km (9 mi) away from the Great Pyramid of Giza, Napoleon Bonaparte's French army won a major victory over a larger Mamluk force, allowing the French to occupy Cairo three days later.

Origins of the Egyptian Expedition

On 1 July 1798, an armada of French ships carrying General Napoleon Bonaparte and the newly christened Armée d'Orient arrived off the coast of Alexandria, Egypt. The French had already undergone a month-long voyage across the Mediterranean, during which they had captured the island of Malta and narrowly evaded a squadron of British warships hunting them. Despite everything they had already experienced, their odyssey was only just beginning. Due to the prevalence of coral reefs, disembarkation was limited to a narrow stretch of coastline at Marabut, some 13 km (8 mi) west of Alexandria. The French rowed ashore in longboats, a process that lasted well into the night; some of the overfilled longboats were capsized by waves, and scores of soldiers drowned. Early the next morning, Bonaparte led his soldiers to Alexandria, which was weakly defended by a garrison of only 500 Egyptian militia and 20 Mamluk warriors. Driven by thirst, the French soldiers rushed over the city's dilapidated fortifications and seized control of Alexandria by midday. The fleet then moved into the harbor to begin unloading the rest of the army; the French expedition to Egypt had begun.

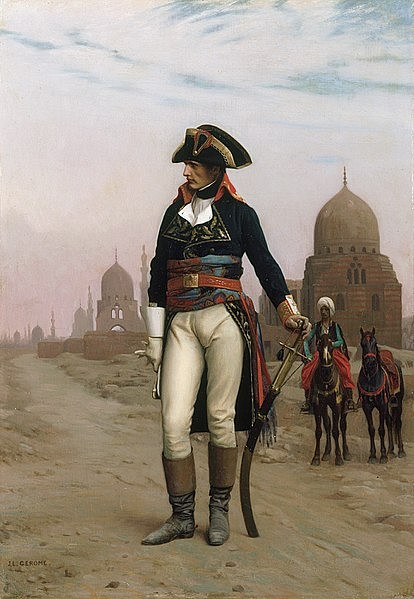

Such an expedition had been suggested by General Bonaparte himself; though Napoleon's Italian campaign had won him fame and glory, Bonaparte knew that he would have to keep winning victories to retain the love of the masses. Moreover, Bonaparte had long dreamed about carving out an eastern empire for himself in the manner of his hero Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE). "Europe is a molehill," he once remarked. "All the great reputations have come from Asia" (Roberts, 159). Indeed, Egypt was only the first part of Bonaparte's grand design; after conquering Cairo, he hoped to march into British India, which he would conquer with the help of anti-British Indian princes, most notably Tipu Sultan. Although the French Directory, the five-man government of the French Republic, had told Bonaparte not to go as far as India, it allowed him to go ahead with his plan to establish a French colony in Egypt. Such a colony would give France a base to expand its influence in the Mediterranean and Africa, and the rumored wealth of Egypt was enticing to the near-destitute French state. The Directory also thought it prudent to get the ambitious Bonaparte as far away from Paris as possible.

Egypt, at this time, was under the nominal rule of the Ottoman Empire, though the true power rested in the hands of a warrior caste known as the Mamluks. The Mamluks had first come to Egypt in 1230, as fighting slaves purchased by the Ayyubid sultan to strengthen his army; indeed, the name Mamluk came from the Arabic word for "bought man" or "slave". These slaves quickly formed themselves into a formidable fighting force; when the French first came to Egypt in 1248 during the Seventh Crusade (1248-1254), the Mamluks defeated them and even captured King Louis IX of France (r. 1226-1270). A decade later, the Mamluks had become the dominant power in Egypt, a position they retained even after the Ottoman takeover of Egypt in 1517. Though the sultan in Constantinople sent pashas to govern Egypt, these administrators were little more than figureheads, and the Mamluk beys continued to rule as they pleased. By 1798, the Mamluks had become unpopular amongst their Egyptian subjects because of their oppressive tax policies, and Bonaparte decided to present himself as the liberator of the Egyptian people. After capturing Alexandria, he wrote a declaration denouncing Mamluk rule:

For too long, this rabble of slaves bought in Georgia and the Caucasus has tyrannized the most beautiful country in the world. In the eyes of God all men are equal, so what entitles the Mamluks to all that makes life comfortable and pleasant? Who owns all the great estates? The Mamluks…if Egypt truly and rightfully belongs to them, let them produce the deeds by which God gave it to them. Once, you had great cities, large canals, and prosperous trade. What has destroyed all this if not the greed, iniquity, and tyranny of the Mamluks? (Strathern, 75)

By declaring war on the Mamluks, and the Mamluks alone, Bonaparte hoped to avoid the wrath of the Ottoman Empire and win the support of the Egyptian people. He ordered his soldiers to present themselves as friends of Islam and to treat any friendly villages and locals they came upon with respect. The Mamluks, meanwhile, were not intimidated by the presence of the French army, which was by this point one of the most efficient fighting forces in the world. Upon learning of the French capture of Alexandria, Murad Bey, one of the Mamluk leaders, promised that he would "slice open their heads like watermelons in the fields" (Strathern, 66).

March Into the Desert

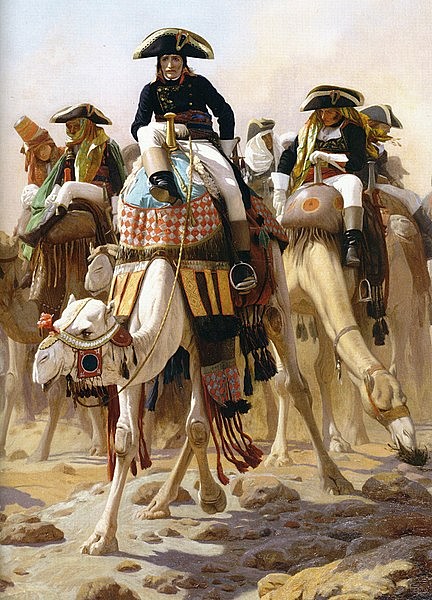

No sooner had Alexandria fallen than Bonaparte began preparing for the capture of Cairo, which required a 240-kilometer (150 mi) march through the desert. As he waited for the remaining horses, cannons, and supplies to be taken off the ships, Bonaparte ordered General Louis Desaix's division to secure Damanhur, a strategically important city on the road to Cairo about 65 km (40 mi) from Alexandria. Desaix was to be followed by three additional divisions, who were to set out from Alexandria as soon as they had finished disembarking. Meanwhile, a fifth division under General Charles-François Dugua was sent to capture Rosetta. Dugua was accompanied by a flotilla of 12 gunboats and 600 sailors led by Captain Jean-Baptiste Perrée, which was to carry most of the army's supplies. After each division had achieved its objective, the entire army was ordered to rendezvous at Rahmaniya for the final push toward Cairo.

Desaix set out for Damanhur on 3 July. Two days later, he was trailed by General Bon's division, with the last two divisions under generals Reynier and Vial leaving Alexandria on the 6th. It was, to put it mildly, a miserable march through the desert. The scorching desert heat rarely dipped below 35 degrees Celsius (95 Fahrenheit), a situation made even more excruciating by the soldiers' woolen uniforms, which were designed for colder climates. The heat led many soldiers to quickly drink all the water in their canteens, only to find that the expected wells along the route had been blocked up or poisoned. Some soldiers were afflicted by trachoma, a form of ophthalmia whereby the blazing sun burns the inside of the eyelids, causing blindness. The French also suffered through the infamous khamsin, the sand-filled windstorms of Egypt, the effects of which were described by one French lieutenant:

Amidst a fine morning, the atmosphere became darkened by a reddish haze, consisting of infinitely many tiny particles of burning dust. Soon we could barely see the disc of the sun. The unbearable wind dried our tongues, burned our eyelids, and induced an insatiable thirst. All sweating ceased, breathing became difficult, arms and legs became leaden with fatigue, and it was all but impossible even to speak. (Strathern, 86)

Overheated, dehydrated, and in some cases blinded, increasing numbers of French soldiers began to fall behind, whereupon they fell into the clutches of the Mamluks and Bedouin tribesmen who had been trailing the invading army. Messengers were kidnapped, and stragglers were butchered; according to one weary officer of General Reynier's division, the road to Damanhur was dotted with the mutilated corpses of French soldiers. Under consistent attack from both the elements and the Mamluks, it is no wonder that many soldiers became demoralized; several Frenchmen committed suicide, while others plotted mutiny.

By 8 July, all four of the malcontented divisions were in Damanhur, with Bonaparte and his staff joining them there the following day. Bonaparte immediately held a war council where he was confronted by his disgruntled generals. Their ringleader was General Mireur, who angrily confronted Bonaparte and accused him of having planned the Egyptian expedition just to satisfy his own vainglorious ambitions. Even Jean Lannes and Joachim Murat, two of Bonaparte's most trusted generals from the Italian campaign, vented their frustrations by throwing their hats in the sand and stomping on them. In response, Bonaparte accused his officers of sedition and threatened to shoot General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, another ringleader, if calm was not restored. Begrudgingly, the officers were persuaded to put aside their frustrations; General Mireur, realizing that his outburst had likely ended his career, went out into the desert and shot himself.

Skirmish at Shubra Khit

Bonaparte had reasserted his authority, but only barely; he knew that he had to give his soldiers a victory, lest he risk losing their support for good. An opportunity was not far off, as Bonaparte received intelligence that the Mamluks were marshaling an army for the defense of Cairo; Murad Bey was leading 4,000 mounted Mamluks and 12,000 fellahin militia down the Nile to meet the French while Murad's co-ruler, Ibrahim Bey, was gathering another force at Cairo itself. On 10 July, one day after leaving Damanhur, General Desaix encountered a detachment of Mamluk cavalry, who were chased off after a brief engagement, a sure sign that the enemy army was close. That same day, the men reached Rahmaniya, where, for the first time, the muddy waters of the Nile came into view. The soldiers rushed into the water and drank "like cattle," and several died from overindulgence (Chandler, 223). On 11 July, General Dugua's division joined the others at Rahmaniya; Dugua had successfully taken Rosetta, and his march had been much easier than that of his comrades.

With all five divisions now in one place, and with morale on the rise, Bonaparte felt that it was the perfect time to seek a proper battle. On 12 July, he ordered his 25,000-man army to advance along the west bank of the Nile in conjunction with Captain Perrée's flotilla, which floated upstream carrying the army's supplies, the officers' wives, and the 167 scientists and scholars known as savants who were accompanying the expedition. Encouraged by the close proximity of the Nile, the soldiers were in good spirits when they encountered Murad Bey's army on 13 July at the village of Shubra Khit; the French moved into position as the military bands played La Marseillaise, and before long each division had taken up the chorus.

Bonaparte organized the infantry of each division into square formations, six ranks deep, with cannons posted on the corners. As opposed to the line formation in which Napoleonic infantry typically fought, a unit in square formation had no vulnerable flanks and could better withstand a cavalry charge. Indeed, even the most determined cavalry charges were likely to break against an infantry square, since most horses would rear and throw off their riders rather than charge into a forest of bayonets. This tactic was particularly useful against the Mamluks; though formidable horseback warriors, the Mamluks' tactics were rather dated, and they had limited experience countering modern European tactics. When the Mamluks charged just after sunrise, they were hit with a hail of French musket fire and grapeshot from the cannons. Those riders who made it to the squares circled the French formations in search of a weak spot but to no avail.

Meanwhile, the French flotilla was attacked by Mamluk gunboats, and fierce hand-to-hand fighting erupted in the Nile as Egyptian militia climbed aboard the French boats. Things got so desperate that the scholarly, and often elderly, savants had to take part in the fighting while Captain Perrée himself suffered a wound to the left arm. At the decisive moment, one of the French cannons hit the commanding Mamluk gunboat where the ammunition was stored; the resulting explosion was so big that "men flew up into the air like birds" (Strathern, 105). The sound of this explosion convinced Murad Bey to call off the fight, and the Mamluks retreated, leaving about 1,000 men killed or wounded on the battlefield. The French reported only 21 casualties, though more realistic estimates place the number closer to 300; most of these casualties were sustained by French sailors in the flotilla fight. For his efforts, Captain Perrée was promoted to rear-admiral by Bonaparte immediately after the battle.

Battle of the Pyramids

After only a few hours of rest following the Battle of Shubra Khit, Bonaparte urged his army onward; they were still less than halfway to Cairo, which Bonaparte hoped to reach as soon as possible. However, as the army marched back into the unforgiving Egyptian desert, discipline started to break down once again. Whenever they spotted a village, the French would attack it; their officers turned a blind eye as the men looted, burned, and killed. While frustration induced some soldiers to these violent acts, others were filled with a sense of overwhelming despair. In his later memoirs, Bonaparte himself commented, "the army was overcome by a vague collective melancholy that nothing could overcome; it was an attack of spleen; several soldiers threw themselves in the Nile in order to have a quick death" (Strathern, 109).

On 18 July, the army reached Wardan, about 105 km (65 mi) away from Shubra Khit. Bonaparte allowed his weary men to rest here for two days but issued orders to resume the march on 20 July. By now, Bonaparte sensed that the decisive battle was growing near; Murad Bey had returned with a new army and was reported to be entrenched near the village of Embabeh on the west bank of the Nile, while Ibrahim Bey commanded another army on the eastern bank, before the very walls of Cairo. At around 2 p.m. on 21 July, the five French divisions arrived at Embabeh where Murad was waiting for them. Against the roughly 25,000 French, Murad commanded some 6,000 mounted Mamluks and perhaps as many as 54,000 Arab fellahin conscripts (this is the high estimate, with other sources putting the number of fellahin at only 15,000). Undeterred, Bonaparte issued his pre-battle Order of the Day to his men, in which he referenced the Great Pyramid of Giza, clearly visible from their position:

Soldiers! You came to this country to save the inhabitants from barbarism, to bring civilization to the Orient and subtract this beautiful part of the world from the domination of England. From the top of those pyramids, forty centuries look down upon you! (Roberts, 172).

Bonaparte once again organized each division into square formation, with cannons posted on the corners. Then, he ordered each division forward. Desaix and Reynier advanced on the right flank, toward the Egyptian center, while the rest of the squares advanced on the left, toward Embabeh itself. At around 3:30 p.m., an unexpected Mamluk charge almost caught Desaix's and Reynier's divisions unawares; their square formations had slackened as they moved through a grove of palm trees. However, the divisions managed to reform the square just in time, breaking the Mamluk charge like waves upon rocks. One French officer described the encounter:

The sabers of the enemy cavalry met the bayonets of our first rank. It was unbelievable chaos: horses and cavalrymen falling on us, some of us falling back. Several Mamluks had their clothes on fire, set alight by the blazing wads from our muskets. I was by the flag and I saw right beside me Mamluks, wounded, in a heap, burning, trying with their sabers to slash the legs of our soldiers in the front rank. We were closed in such tight rank that they must have believed we were joined together. (Strathern, 122)

As the panicked Mamluk cavalrymen rode between divisions, trying desperately to find an opening, Bonaparte seized the opportunity. He ordered Bon's and Vial's divisions to attack the enemy entrenchments at Embabeh. Murad Bey sent the right wing of his cavalry to meet this attack, but this, too, quickly broke apart against the French squares. Before long, Bon's men stormed the village, chasing the 2,000-man garrison into the Nile; the French fired volleys at the fleeing Arab militiamen, who tried desperately to swim across the river to the safety of Ibrahim Bey's army, which was helplessly watching the fight from the opposite bank. At least 1,000 of these men were drowned, and 600 were shot down by the French muskets. By 4:30 p.m., the battle was over. Murad Bey took his 3,000 surviving Mamluks and fled toward his palace at Giza. It was a resounding victory for the French, who reported only 29 killed and 260 wounded, compared to nearly 10,000 Egyptian casualties.

Aftermath

Three days after the battle, Bonaparte's army finally entered Cairo. Their coming went unopposed since both Murad and Ibrahim had fled into Upper Egypt; Bonaparte sent Desaix to track them down, and he set about establishing a French administration in Cairo. The French victory at the Battle of the Pyramids marked the high watermark of Napoleon's Egyptian campaign; only days later, the French fleet would be destroyed at the Battle of the Nile, cutting Bonaparte's army off from Europe. A year later, Bonaparte would abandon his army in Alexandria after recognizing the expedition's failure and would make his way back to France, where he seized power in the Coup of 18 Brumaire. His army would linger in Egypt until its surrender to Anglo-Ottoman forces in 1801.