The trial and execution of Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), formerly the queen of France, was among the opening events of the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution (1789-1799). Accused of a series of crimes that included conspiring with foreign powers against the security of France, Marie Antoinette was found guilty of high treason and executed on 16 October 1793.

Since at least the time of the affair of the diamond necklace in 1785, Marie Antoinette was immensely unpopular in France, the subject of wild rumors and scandalous libelles. Accused of being an Austrian spy, a careless spendthrift, and a morally bankrupt deviant, her association with France’s monarchy helped to lessen its popularity at the start of the Revolution. At the outbreak of the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797), she hoped to bring about the Revolution’s destruction by sending military secrets to her contacts in Austria, but was imprisoned by the revolutionaries alongside her family following the Storming of the Tuileries Palace in August 1792.

After the trial and execution of Louis XVI in January 1793, she remained imprisoned along with her sister-in-law, Madame Elizabeth, and her children: the fourteen-year-old princess Marie-Thérèse, and the eight-year-old Louis-Charles, who was recognized by royalists as Louis XVII, rightful king of France.

The Widow Capet

The execution of Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) left the king’s widow, Marie Antoinette, overwhelmed with grief. Like a ghost, she haunted her chambers in the Tower of the Temple, the Paris prison fortress where she and her children were being detained by the revolutionary government. In the days after her husband’s death, the former queen barely spoke and rarely ate. She refused to even go into the gardens for fresh air, since doing so required passing by the king’s empty chambers, now painfully silent. Marie Antoinette had turned pale and sickly during her imprisonment, her hair having prematurely gone white from stress. No longer referred to reverently as “Her Majesty”, she was now known as “the Widow Capet” or, more plainly, as Antoinette Capet.

Despite her sorrow, the queen would have had reason to believe that the worst was over in February 1793. Louis’ death put a stop to the steady stream of lawyers and public officials who had come to meet with the ex-king, restoring to the royal prisoners some much needed privacy. Prison guards no longer bothered to monitor their private conversations, and Marie Antoinette was even allowed to commission a new black dress so she could properly mourn her husband. For a moment, it was even conceivable that Marie Antoinette and her children might have a chance at freedom. The king’s blood had been required for the Republic’s survival, but despite her reviled reputation, Marie Antoinette had not yet been charged with any crimes and her execution was not on the National Convention’s agenda. Indeed, Louis XVI had been assured before his own death that no harm would befall his family, a promise that was reiterated to Marie Antoinette herself, who was told that the idea of her execution was a “gratuitous horror” contrary to the Revolution’s policy (Fraser, 408).

Yet, these promises were made at a time of French ascendency, when revolutionary armies were pushing the Coalition back in both Germany and Belgium. Within a month, however, fortune had turned against the French. February saw the list of France’s enemies grow to include Britain, Spain, and the Dutch Republic, while on 18 March, the Austrians won a major victory at the Battle of Neerwinden, reclaiming Belgium for their emperor and forcing the French back on the defensive. That same month saw the outbreak of the brutal War in the Vendée, a Catholic and royalist rebellion that recognized Marie Antoinette’s son, eight-year-old Louis-Charles, as King Louis XVII of France.

Feeling themselves backed into a corner, revolutionary leaders lashed out against their own “Austrian she-wolf” and her royal pups; Maximilien Robespierre demanded the former queen be hauled before the new Revolutionary Tribunal for trial, reminding his colleagues that she had previously passed military secrets to France’s enemies and should not be left unpunished to enjoy the fruits of her treasons. After the establishment of the Committee of Public Safety on 6 April, the Republic cracked down on the old nobility, arresting such prominent figures as the Duke of Orléans and the Prince de Conti. The queen was subjected to sporadic nighttime searches of her chambers, and the Jacobins ordered her windows to be barred.

Immediately, the queen’s position became uncertain. Her nephew, Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor (r.1792-1806) was evidently uninterested in securing the freedom of an aunt he had never met. He shot down any ideas to ransom her or exchange her for valuable French prisoners of war, and Austria’s recent military success meant that he was unlikely to accept entreaties of peace from France. The emperor’s top general in Belgium, the Prince of Saxe-Coburg, saw no strategic reason to divert men and resources for a rescue attempt when he already had France’s armies on the run. Additionally, Austrian officials were reluctant to negotiate with the unpredictable revolutionary “brigands”, fearing that any attempt to discuss Marie Antoinette’s release would provoke them to bring her to trial.

A Stolen Son

The emperor’s inaction vexed many of Marie Antoinette’s remaining friends. Count Axel von Fersen, the dashing Swedish soldier who had once been the queen’s paramour, declared his intent to gather a group of brave men, ride to Paris, and storm the Temple in a veritable suicide mission. Count de La Marck urged the Austrian court at Vienna to offer a ransom for the queen’s release, emphasizing how embarrassing it would be “for the imperial government if history could say one day that 40 leagues away from formidable and victorious Austrian armies, the august daughter of Maria Theresa has perished on the scaffold without any attempt being made to save her” (Fraser, 420).

In the end, Fersen was dissuaded from his swashbuckling plan and La Marck realized the government would be of no help. Only clandestine, private schemes could save the queen. One such attempt was made in March 1793, just as the queen’s position first began to sour. The plan was to smuggle Marie Antoinette and her family out of the Temple disguised in oversized military coats, to be taken first to Normandy and then on to England. The plot was foiled when one of the conspirators lost his nerve and failed to procure the necessary forged passports. Another plot was thwarted in June, when Antoine Simon, a former cobbler and influential member of the Paris Commune, happened across a conspirator suspiciously lurking outside the queen’s chambers.

Amidst these failed rescue plots, Marie Antoinette’s situation only worsened. By June, the Vendean rebels had beaten back every French Republican army sent against them, while key French cities rose up against Jacobin rule in the federalist revolts. Again, the frustrated Jacobins turned their thoughts to Marie Antoinette, who had taken to seating her son atop a cushion at the head of the table during meals; the Jacobins took this as an indication that Marie Antoinette was recognizing Louis-Charles’ claim to the throne.

On the night of 3 July, commissioners arrived at the Temple, informing Marie Antoinette that they had come to collect her son. They explained that they had uncovered a plot to abduct the prince and only wished to bring him to a more secure room in the prison. Marie Antoinette saw through their lies and refused to give up her son, who jumped weeping into her arms. For an hour, the queen refused to be swayed, even after the commissioners dropped the pretense and threatened to kill her. Only when they threatened to kill her daughter instead did she finally relent. Louis-Charles was taken away, never to see his mother again. For days afterward, the family was haunted by the sounds of the boy’s incessant sobbing, audible from the room he was removed to. A distraught Marie Antoinette would spend her days watching the prison’s hallway from her room, in the desperate hope that she would catch a glimpse of her son as he was taken to the gardens for a walk.

The revolutionaries intended to reeducate the young prince in the spirit of republicanism and to erase all pretensions to royalism from his mind. Unfortunately, they entrusted his well-being to perhaps the worst possible person. Antoine Simon was barely literate and wholly cruel, viciously beating Louis-Charles every time he found the boy crying. Simon amused himself and the guards by plying the boy with wine until the point of drunkenness and by teaching Louis-Charles to speak in obscenities. Once a robust and healthy child, Louis-Charles had become sickly during his imprisonment, and had at one point sustained a nasty, yet accidental, injury to his crotch. Working with the “ultra-radical” journalist Jacques-René Hébert, Simon used the boy’s physical condition as “evidence” that he had been physically and sexually abused by his mother and Madame Elizabeth. Hébert and Simon coerced the boy into signing a written statement that his mother had inflicted such incestual abuse upon him. This horrified the royal family, as Marie-Thérèse and Madame Elizabeth wrote their own statements denouncing the claims as lies.

Carnation Plot

At 2 am on 1 August, a month after Louis-Charles was taken away, Jacobin officials roused Marie Antoinette from her sleep and ordered her to dress. After a hurried goodbye to Marie-Thérèse, the queen was taken under armed escort to the prison of the Conciergerie, a damp, dark place that was often the final stop for prisoners on the road to the guillotine. Referred to by guards as “Prisoner 280,” she was kept under constant surveillance, her only privacy being a four-foot-high curtain behind which she dressed and used the toilet. Far from the seclusion of the Temple, the Conciergerie was bustling with lawyers, guards, and visitors, as well as people who wished to catch a glimpse of the captive queen.

One of Marie Antoinette’s visitors, Alexandre de Rougeville, dropped a carnation at the queen’s feet. When she picked it up, she discovered a note hidden amongst the petals. It contained details of a rescue mission, in which she would be taken away in a waiting carriage to Germany. The plot was given away by one of the queen’s guards, who had either been part of the scheme and lost his nerve, or had deduced it from Rougeville’s subsequent visits. Following the plot's discovery, Marie Antoinette was taken to a more secure cell where she was interrogated for two days. The queen kept her composure despite the relentless questioning, asserting that her interests lay only in what was best for her son, and that her only enemies were those who wished to harm her children.

Around this time, the Committee of Public Safety met to decide the queen’s fate. The loudest voice for her execution came from Hébert, who claimed to speak on behalf of the people. He stated that the queen’s death should be a collaboration between the city of Paris and the Revolutionary Tribunal, effectively binding the people to the government with her blood. “I have promised the head of Antoinette,” Hébert declared. “I will go and cut it off myself if there is any delay in giving it to me,” (Fraser, 425). In the end, the Jacobin-controlled Committee reached an agreement with Hébert; the queen would die to appease the people, and the leadership of the moderate Girondins would be executed for the Jacobins' benefit. Thus, the fate of the queen was sealed before she was even brought to trial.

The Trial

On the night of 12 October, Marie Antoinette was again woken from her sleep and brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal to be indicted. After denying the charges listed against her, she was given the right to a defense counsel and sent back to her cell. Unlike Louis XVI, who had been given weeks to prepare a defense, Marie Antoinette had only hours; her head lawyer, Claude-François Chauveau-Lagarde, urged her to write the Tribunal and ask for three more days to prepare. She did so, but her request went unanswered.

The queen’s trial began on 14 October 1793. Still pale and sickly, clad in widow’s black, the queen’s appearance shocked many onlookers who had been expecting to see the ferocious Austrian she-wolf of rumor. Marie Antoinette was introduced to the court and then asked to sit as the trial began, commencing hours of the grueling cross-examination of 40 witnesses. While the trial of the king had involved solid evidence, including signed documents, the charges against Marie Antoinette were more abstract, mostly based on rumors and hearsay. The first witness, a captain in the Versailles National Guard, spoke of supposed drunken orgies that he admittedly had not actually seen with his own eyes, while another witness recounted a baseless rumor that the queen had gotten the Swiss Guards drunk prior to the Storming of the Tuileries Palace.

Upon cross-examination, Marie Antoinette responded to the allegations with short, non-committal replies: “I do not recall” and “I never heard talk of anything like that.” She denied being the one to convince her husband to flee France during the ill-fated flight to Varennes in 1791, claiming that she had never exerted such control over the king’s decisions. On another occasion, the prosecution presented documents supposedly signed by the queen; when Marie Antoinette asked for the date on the documents, it was revealed that they were “signed” after Marie Antoinette was already imprisoned. The only time she gave ground was under questioning regarding the misuse of funds going toward her private residence, the Petit Trianon; “perhaps more was spent than I would have wished” (Fraser, 433).

With the prosecution’s case faltering, Hébert decided it was time to reveal his charge of incest. At this accusation, the queen’s composure dropped. “Did you witness it?” she snapped at Hébert, refusing to comment further on the charge. When the Tribunal’s president asked Marie Antoinette why she had refused to answer the question, the queen replied, “if I have not replied, it is because Nature itself refuses to respond to such a charge laid against a mother” (Fraser, 431). She then made an emotional appeal to all the mothers in the courtroom, some of whom responded positively and called out for the court’s proceedings to be stopped.

The trial went on until 11 pm when it was adjourned for the night. It picked up again at 8 am the next morning and continued for 16 hours. While some of the accusations had more merit than others, such as the claim that she had been sending military secrets to France’s enemies, most of the evidence itself was tenuous at best. Marie Antoinette was confident in her performance and believed that the worst-case scenario would be a life sentence. She was unaware that her fate had been decided long before.

At 4 in the morning on 16 October, she was found guilty of the three main charges against her: conspiring with foreign powers, the depletion of the state treasury, and of committing high treason by acting against the security of the French state. The prosecution asked for, and was granted, the death penalty. The queen was condemned to be executed later that day. When asked if she had anything to say, Marie Antoinette simply shook her head.

Execution

In her last hours, Marie Antoinette was allowed writing materials. In a letter to Madame Elizabeth, she wrote of her deepest regret in having to leave her children: “you know that I have lived on only for them and for you, my dear and tender sister” (Fraser, 436). She wrote of how she would soon be rejoining Madame Elizabeth’s brother, meaning Louis XVI; Elizabeth herself would join them when she was guillotined the following May. Writing another letter to her children, Marie Antoinette asked them to look after one another, imploring Marie-Thérèse to forgive Louis-Charles’ lies. “Think of his age and how easy it is to make a child say what one wants, even things he doesn’t understand” (ibid). Of her children, only Marie-Thérèse would live to see adulthood, as Louis-Charles would die two summers later, still in captivity.

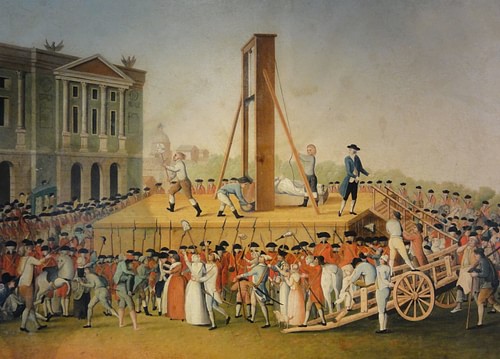

After writing her letters, Marie Antoinette refused to take breakfast, believing such nourishment to be pointless since “everything is over for me.” She was dressed in a plain white dress, her hair cut, and her hands bound. Humiliatingly, Marie Antoinette had to ask the executioner’s permission to briefly unbind her hands so she could relieve herself in a corner. At 11 am, she was taken to the guillotine in an open cart, denied the dignity of a closed carriage that had been afforded to her husband.

When she reached the scaffold on the Place de la Revolution, she mustered what pride she had left and climbed the steps. After apologizing to the executioner for accidentally stepping on his foot, she was guillotined at 12:15 in the afternoon, to the cheers of a joyous crowd. With her death, France was free of its Austrian she-wolf, of the so-called “Madame Deficit” who had bankrupted the nation both morally and financially. What it got in return was ten months of blood, for Marie Antoinette was one of the first high profile victims of the Reign of Terror.