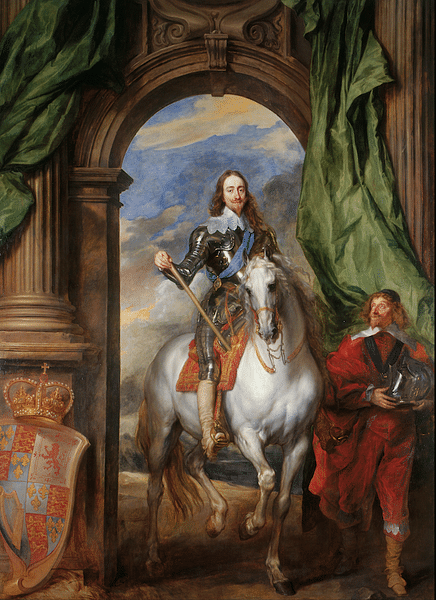

The English Civil Wars (1642-1651) were caused by a monumental clash of ideas between King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) and his parliament. Arguments over the powers of the monarchy, finances, questions of religious practices and toleration, and the clash of leaders with personalities, who passionately believed in their own cause but had little empathy towards any other view, all contributed to the decade-long conflict which saw over 600 battles and sieges, thousands of deaths, the execution of Charles, abolition of the monarchy, and the proclamation of England as a republic.

The Three Civil Wars

The conflict between the Royalists ('Cavaliers') and Parliamentarians ('Roundheads') which rocked Britain is usually divided into three distinct parts:

- The First English Civil War (1642-1646)

- The Second English Civil War (Feb-Aug 1648)

- The Third English Civil War or Anglo-Scottish War (1650-1651)

The causes of all three conflicts, sometimes collectively known as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (England, Scotland, and Ireland), were much the same except that following Charles I's execution in 1649, the figurehead for the Royalists during the Third Civil War became his son Charles II of Scotland.

Historians do not agree on the precise causes of the Civil Wars, and so the following is a summary of the various viewpoints with no particular weight given to one cause over another.

A Multitude of Causes

The principal causes of the English Civil Wars may be summarised as:

- Charles I's unshakeable belief in the divine right of kings to rule

- Parliament's desire to curb the powers of the king

- Charles I's need for money to fund his court and wars

- Religious differences between the monarch, Parliament, Scottish Covenanters, and Irish Catholics

- The personalities of key leaders on both sides, which did not allow for compromise

- A rise in the number and economic power of the new gentry who now sought political change

- A belief that the king was a wicked warmonger and had to be removed

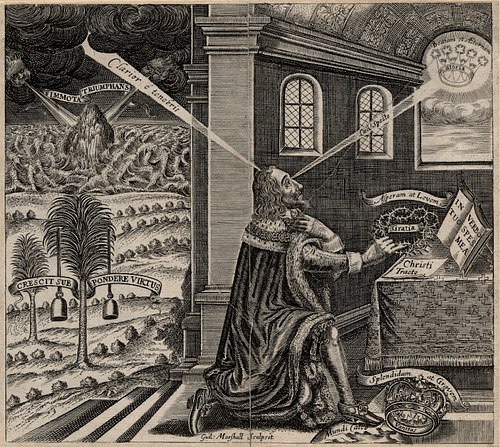

The Divine Right of Kings

Charles was very much like his father James I of England (r. 1603-1625) in that he had an unshakeable belief in his divine right to rule, given to him, he thought, by God, and so no man, be it politician or soldier, should ever question his reign. The English king once stated: "Parliaments are altogether in my power…As I find the fruits of them good or evil, they are to continue or not to be" (McDowall, 88). This belief was never shaken throughout the wars, as seen in 1649 when he refused to recognise the authority of those who had put him on trial for treason:

I would know by what power I am called hither…I would know by what authority, I mean lawful…Remember, I am your king, your lawful king…a king cannot be tried by any superior jurisdiction on earth.

(Ralph Lewis, 160)

Charles' personality had much to do with the crisis. A little shy and lacking confidence after a childhood away from the limelight when his elder brother was groomed for the crown, Charles was thrust into the glare of politics when Henry, Prince of Wales died of fever aged 18. Never quite trusting those around him, inflexible, repeatedly unwilling to make concessions, and not particularly receptive to criticism, Charles was perhaps led into making certain decisions that he himself did not whole-heartedly believe in or which were, at best, naive in their ignorance of opposing and more modern views. The king is also accused of being unaware of the different social, economic, and religious identities within his own kingdoms, particularly regarding Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, but also in parts of England where there were differences between regions and between rural and urban communities. In fairness, similar criticisms could be made of his opponents with such bullish MPs as John Pym (1583-1643) and Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) who were utterly convinced God was on their side and not with the king.

There is also the argument that Charles inherited a difficult situation, his father being the first Stuart monarch after the Tudors. The kingdom was a united one in name only. There had been turbulent religious reforms going back to Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547), and the fallout of these was still being felt. Tensions between monarch and Parliament were not new either, and the antiquated system of state finances did not help smooth the relationship. Granted that the situation was not an easy one, some historians would accuse Charles of making it much worse, turning only potential problems into very real ones (Gaunt, 18).

The position of the king as an absolute monarch in Charles' own mind should have been seriously challenged by such events as the 1628 Petition of Right when Parliament demanded the king stop trying to raise money outside of that institution. Other demands included an end to both imprisonment without trial and the use of martial law against civilians. Desperately in need of money for his war with France, the king was obliged to agree to the demands but it in no way altered his opinion of his status as a monarch who had no need to consult anyone on how to govern his kingdom.

Disputes Over Finances

The monarchy traditionally required Parliament to meet and pass favour on royal requests for money, which typically entailed MPs deciding budgets and raising taxes. Charles grew tired of Parliament's obstinacy and insistence that money be accounted for and spending curbed. The king repeatedly called and dismissed parliaments but eventually grew tired of this situation and decided to rule alone. Parliament was not called between 1629 and 1640, a period often called the 'Personal Rule' of the king. This strategy worked well enough until the king desperately needed funds in 1639 to pay for his campaigns against a Scottish army, which had occupied the north of England, and a serious rebellion in Ireland, both fuelled by religious differences and the king's high-handed policies.

The king's efforts to raise money during his 'Personal Rule' had met with only limited success. He borrowed from bankers, extracted new customs duties, imposed forced loans on the wealthy, sold monopolies, and widened the extraction and use of Ship Money (originally imposed on coastal communities only to help fund the navy). He also imposed fines based on archaic forest laws and increased fines imposed by courts. Many of these measures were deeply unpopular with the merchant classes and local gentry, who were more numerous than ever before. Such men were keen to see a political role to match their importance to the economy, and they were unwilling to fund the whims of a monarch who caused what they saw as unnecessary wars and who supported a declining and outdated feudal aristocracy. It did not help that Charles spent grandly on new palaces and art collections. Parliament, knowing the king had nowhere else to go for more cash, could now force Charles into political reforms and concessions.

Charles called what became known as the Short Parliament in the spring of 1640 to help raise an army, but this failed after three frustrating weeks of discussion. As a result, the king could only muster a weak militia force against the Scots in the so-called Bishops' Wars (1639-1640). These wars ended in Charles making concessions to Scotland in the Treaty of Ripon in October 1640. Scotland was permitted its religious freedom, and the leaders on the battlefield were promised a handsome sum in cash to stand down. The king then had the practical problem of where exactly to get this money from without Parliament.

Without much choice in the matter, another Parliament was called in November 1640, and so began a period known as the 'Crisis of the Monarchy'. MPs seized their opportunity with the Long Parliament, as it became known, to guarantee their future survival. Money would be raised to pay off the Scots, but only on the condition that laws were passed which meant a parliament must be called at least once every three years, that it could not be dissolved by the monarch's wishes alone, royal ministers now had to be approved by Parliament, and Ship Money was made illegal. The king agreed but then blithely ignored his promises.

One of the decisions of Parliament which had particularly struck Charles and soured relations more than ever was the trial for treason and execution of his closest advisor Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Stafford (1593-1641) in May 1641. Stafford had been accused of preparing to bring an Irish army into England to aid the king, for which there was not much evidence. More significant, perhaps, was Parliament's fear of what exactly the gifted and utterly ruthless Stafford planned in the future regarding themselves. As far as Charles was concerned, Parliament had drawn first blood.

In October 1641 the king needed money for yet another army when a rebellion broke out against English rule (some would say tyranny) in Ireland, fuelled by grievances over massive English land confiscations and the exclusive employment of English and Scottish immigrants on many large estates. Ulster was a particularly bloody battleground while Charles and the English Parliament wrangled over the formation of an army necessary to quell the rebellion. Parliament was particularly anxious that the king use such a force in Ireland and not against themselves. These fears were perhaps not unfounded, and the king's attempted arrest of five MPs in January 1642 hardly instilled confidence. The group, who included John Pym, had written the Grand Remonstrance listing the king's abuses of power and which was passed by Parliament in November 1641. The Remonstrance was then made public. In retaliation for the arrests, the Parliamentarians locked the gates of London, preventing Charles from entering his own capital. However, the king was encouraged by the distinct lack of unity in Parliament as the Remonstrance had only been accepted by 159 votes to 148. Some MPs believed that the king's powers were being unjustly infringed upon (for example, that he could not choose his own counsellors or military leaders), while the more radical members were keen to curb those powers even further. A military solution to the deadlock might now be Charles' best tactic. The king relocated from Hampton Court to York and then to Nottingham in August 1642, where a royal army was formed.

Religious Differences

As we have seen, the multiple threads of discord that caused the English Civil Wars were intertwined in a complex political, religious, and military knot. Charles frequently created new enemies because of his religious policies. In 1627, Charles began to promote the Arminians, a branch of the Anglican Church that emphasised ritual, sacraments, and the clergy, and not the style of preaching seen in other branches closer to Calvinism. Some saw this move as a dangerous shift back towards Catholicism, a sign of a secret Papist conspiracy to reverse the English Reformation, an idea which was widely circulated in the 17th century by word of mouth and the printing press, adding fictional fuel to a bonfire of conspiracy theories that went all the way back to the one real conspiracy: the Gunpowder Plot to blow up King and Parliament in 1605.

Charles was not, in fact, a Catholic but a High Anglican, that is he had certain sympathies with such aspects of the Christian Church as ceremony, the elevation of the clergy and bishops, and what he perceived as the beauty and order provided by certain decorations within the church building itself. For many, though, it was difficult to distinguish this from 'Popish' practices and Roman Catholic doctrine. There were, too, more concrete concerns over the Arminians' seeming support of an absolute monarchy.

In 1633, the king appointed William Laud (1573-1645), an Arminian, as the Archbishop of Canterbury, head of the Church of England. Laud was detested by the Puritans, who remained a rich and powerful section of English society and who had a strong presence in Parliament. Many MPs and army officers were Independents or Congregationalists, that is they wanted less power in the hands of bishops and more inclusion in the Church. Many wanted greater freedom for 'independent' congregations that assembled according to the individual believers' consciences and their own interpretation of the Bible. Laud outraged the Puritans when he reintroduced what were widely seen as Catholic practices into the more austere Anglican Church. These included decorating churches, railing off the altar or communion table to restrict access only for the clergy, and encouraging music. Laud banned preaching on any day other than a Sunday and replaced this with the Catechism. He also banned the weekday lectures that Puritans so valued. From Laud's and the king's perspective, these religious changes were slight and intended to emphasise ritual and order, but for the Puritans, this was a direct attack on the achievements of the Reformation. With no real means to protest or obstruct these measures, and with punishments and fines for non-compliance, many Puritans decided to emigrate and find greater religious freedom in North America or the Netherlands.

Charles also upset the Scottish Kirk and its Presbyterian church leaders by trying to install bishops there. The introduction of a new prayer book in 1637 was made without even consulting the Kirk. The Presbyterians (moderate Puritans who believed in a church hierarchy) much preferred to stick to their system where each congregation was led by a minister who in turn reported to the Synod, an elected supervisory council of elders. Further, the Scots believed Charles had no right to impose anything on the Scottish Church, a point many were willing to fight for.

Far from being a problem of ecclesiastical debate, these issues boiled over onto the battlefield in the Bishops' Wars mentioned above. The Scottish Presbyterian Church was determined to defend its independence and so became an active ally of the Parliamentarians in the English Civil Wars before switching sides in support of the Royalists when Parliament was deemed the greater threat. Those Scots who sought an alliance with England were known as the Covenanters from the agreement known as the National Covenant of February 1638. Those who signed the agreement swore to defend the Presbyterian Church, even by military means if necessary.

War

In England, meanwhile, as we have seen, the situation between King and Parliament had worsened considerably. By 1642, both sides were gathering arms, fortifying the cities they controlled, and preparing for war. The first major battle was at Edgehill in October. The result was indecisive, as it would be in many of the battles that followed. While often seen as a war that did not involve a great number of civilians, it is estimated that at least one in four adult male Britons fought at some point, one in ten people in urban areas lost their homes, and the vast majority of people had to bear heavy taxes, even if they themselves avoided the actual fighting.

As the Civil War progressed so new motives arrived for supporters on both sides. Charles' policy in Ireland further alienated the king from many of his English subjects. The king had struck a deal with Irish rebels so that Irish Catholic troops might bolster his army. This never came about in reality as most of the troops from Ireland were Charles' English soldiers now released from policing duties there, and even these were few in number. The episode did raise the serious question as to Charles' loyalty to the Anglican Church.

More and more people came to see the king as a despot and wilful warmonger who no longer had his people's interests foremost in his mind. The capture of the king's personal writing cabinet at the Battle of Naseby in 1645 revealed that the king had no intention of ever compromising with Parliament. Already for many, there could be no peaceful resolution to the conflict. This was particularly so after the Second Civil War and the invasion of a Scottish army into England. The king, even in self-imposed exile on the Isle of Wight, came to be viewed as a 'man of blood', a biblical term for a ruler who waged war against his own people. In his treaty with the Scots known as the Engagement of December 1647, he had even promised to favour the Presbyterian Church in England, disband the English army and rely only on a Scottish one, and suppress radical religious groups. This was the final straw.

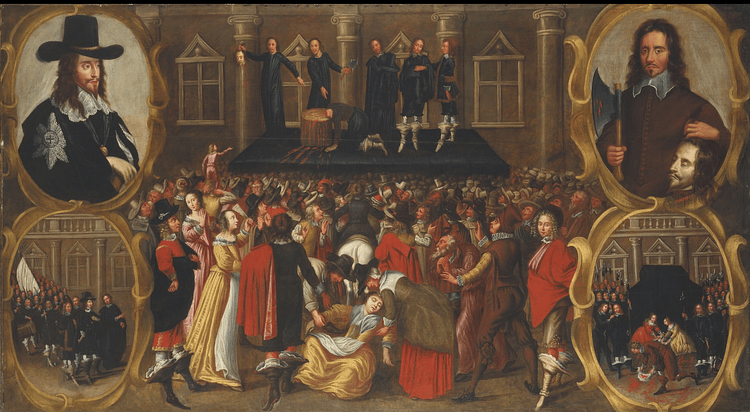

With more money and a more professional army, the Parliamentarians were the victors again at the Battle of Preston in 1648. Charles I was tried and found guilty of treason to his own people and government. The king was executed on 30 January 1649. The monarchy and the House of Lords were abolished, and the Anglican Church was reformed. Scotland remained loyal to the crown, and Charles' eldest son Charles was, by right of birth, its king. However, a Scottish army was again defeated by an English one in the so-called Third English Civil War, and the would-be Charles II was obliged to flee to France.

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) ruled the 'Commonwealth' republic as Lord Protector. When Cromwell died, his chosen successor, his son Richard Cromwell, was not supported for long, and so, to avert another civil war, there was the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. Charles returned from France to become Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), but he now had to rule alongside a much more powerful Parliament.